Institutional Development of the Chinese National People's Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

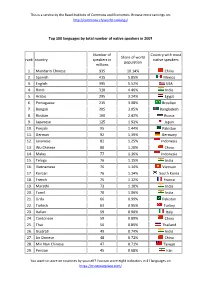

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with Some Research Findings

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 411-442 411 © The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with some Research Findings Jane S. Tsay∗ Abstract Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan (Taiwan Southern Min) speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. This corpus is special in several ways: (1) It is a Minnan corpus; (2) It is a speech-based corpus; (3) It is a corpus of a language that does not yet have a conventionalized orthography; (4) It is a collection of longitudinal child language data; (5) It is one of the largest child corpora in the world with about two million syllables in 497,426 lines (utterances) based on about 330 hours of recordings. Regarding the format, TAICORP adopted the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [MacWhinney and Snow 1985; MacWhinney 1995] for transcribing and coding the recordings into machine-readable text. The goals of this paper are to introduce the construction of this speech-based corpus and at the same time to discuss some problems and challenges encountered. The development of an automatic word segmentation program with a spell-checker is also discussed. Finally, some findings in syllable distribution are reported. Keywords: Minnan, Taiwan Southern Min, Taiwanese, Speech Corpus, Child Language, CHILDES, Automatic Word Segmentation 1. Introduction Taiwanese Child Language Corpus is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. -

New Foreign Policy Actors in China

Stockholm InternatIonal Peace reSearch InStItute SIPrI Policy Paper new ForeIgn PolIcy new Foreign Policy actors in china 26 actorS In chIna September 2010 The dynamic transformation of Chinese society that has paralleled linda jakobson and dean knox changes in the international environment has had a direct impact on both the making and shaping of Chinese foreign policy. To understand the complex nature of these changes is of utmost importance to the international community in seeking China’s engagement and cooperation. Although much about China’s foreign policy decision making remains obscure, this Policy Paper make clear that it is possible to identify the interest groups vying for a voice in policy formulation and to explore their policy preferences. Uniquely informed by the authors’ access to individuals across the full range of Chinese foreign policy actors, this Policy Paper reveals a number of emergent trends, chief among them the changing face of China’s official decision-making apparatus and the direction that actors on the margins would like to see Chinese foreign policy take. linda Jakobson (Finland) is Director of the SIPRI China and Global Security Programme. She has lived and worked in China for over 15 years and is fluent in Chinese. She has written six books about China and has published extensively on China’s foreign policy, the Taiwan Strait, China’s energy security, and China’s policies on climate change and science and technology. Prior to joining SIPRI in 2009, Jakobson worked for 10 years for the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA), most recently as director of its China Programme. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China

Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China In most liberal democracies, commercialized media is taken for granted, but in many authoritarian regimes, the introduction of market forces in the media represents a radical break from the past, with uncer- tain political and social implications. In Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China,DanielaStockmannarguesthatthecon- sequences of media marketization depend on the institutional design of the state. In one-party regimes such as China, market-based media promote regime stability rather than destabilizing authoritarianism or bringing about democracy. By analyzing the Chinese media, Stockmann ties trends of market liberalism in China to other authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the post- Soviet region. Drawing on in-depth interviews with Chinese journalists and propaganda officials as well as more than 2,000 newspaper articles, experiments, and public opinion data sets, this book links censorship among journalists with patterns of media consumption and media’s effects on public opinion. Daniela Stockmann is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University. Her research on political communication and public opin- ion in China has been published in Comparative Political Studies, Political Communication, The China Quarterly,andtheChinese Jour- nal of Communication,amongothers.Her2006 conference paper on the Chinese media and public opinion received an award in Political Communication from the American Political Science Association. i Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 ii Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 Communication, Society, and Politics Editors W. -

The Challenges of China's Growth

The Challenges of China’s Growth THE HENRY WENDT LECTURE SERIES The Henry Wendt Lecture is delivered annually at the American Enterprise Institute by a scholar who has made major contributions to our understanding of the modern phenomenon of globalization and its consequences for social welfare, government policy, and the expansion of liberal political institutions. The lecture series is part of AEI’s Wendt Program in Global Political Economy, estab- lished through the generosity of the SmithKline Beecham pharma- ceutical company (now GlaxoSmithKline) and Mr. Henry Wendt, former chairman and chief executive officer of SmithKline Beecham and trustee emeritus of AEI. GROWTH AND INTERACTION IN THE WORLD ECONOMY: THE ROOTS OF MODERNITY Angus Maddison, 2001 IN DEFENSE OF EMPIRES Deepak Lal, 2002 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF WORLD MASS MIGRATION: COMPARING TWO GLOBAL CENTURIES Jeffrey G. Williamson, 2004 GLOBAL POPULATION AGING AND ITS ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES Ronald Lee, 2005 THE CHALLENGES OF CHINA’S GROWTH Dwight H. Perkins, 2006 The Challenges of China’s Growth Dwight H. Perkins The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perkins, Dwight H. (Dwight Heald), 1934- The challenges of China’s growth / by Dwight H. Perkins. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. -

Communications and China's National Integration: an Analysis of People's

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY •• AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 5 - 1986 {76) COMMUNICATIONS AND CHINA'S NATIONAL INTEGRATION: AN , ANALYSIS OF PEOPLE'S DAILY •I AND CENTRAL DAILY NEWS ON • THE CHINA REUNIFICATION ISSUE Shuhua Chang SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of 0 c:.•• MARylANd_. 0 ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

History Has Provided Ample Proof That the State Is the People, and the People Are the State

History has provided ample proof that the state is the people, and the people are the state. Winning or losing public support is vital to the Party's survival or extinction. With the people's trust and support, the Party can overcome all hardships and remain invincible. — Xi Jinping Contents Introduction… ………………………………………1 Chapter…One:…Why…Have…the…Chinese… People…Chosen…the…CPC?… ………………………4 1.1…History-based…Identification:… Standing…out…from…over…300…Political…Parties……… 5 1.2…Value-based…Identification:… Winning…Approval…through…Dedication… ………… 8 1.3…Performance-based…Identification:… Solid…Progress…in…People's…Well-being… ……………12 1.4…Culture-based…Identification:… Millennia-old…Faith…in…the…People… …………………16 Chapter…Two:…How…Does…the…CPC… Represent…the…People?… ……………………… 21 2.1…Clear…Commitment…to…Founding…Mission… ………22 2.2…Tried-and-true…Democratic…System… ………………28 2.3…Trusted…Party-People…Relationship… ………………34 2.4…Effective…Supervision…System… ………………………39 Chapter…Three:…What…Contributions…Does… the…CPC…Make…to…Human…Progress?… ……… 45 3.1…ABCDE:…The…Secret…to…the…CPC's…Success…from… a…Global…Perspective… ………………………………… 46 All…for…the…People… …………………………………… 46 Blueprint…Drawing… ………………………………… 47 Capacity…Building �������������� 48 Development…Shared… ……………………………… 50 Effective…Governance… ……………………………… 51 3.2…Community…with…a…Shared…Future…for…Humanity:… Path…toward…Well-being…for…All… …………………… 52 Peace…Built…by…All… …………………………………… 53 Development…Beneficial…to…All �������� 56 Mutual…Learning…among…Civilizations… ………… 59 Epilogue… ………………………………………… 62 Introduction Of the thousands of political parties in the world, just several dozen have a history of over 100 years, while only a select few have managed to stay in power for an extended period. -

In a Fortnight: China Conducts Anti-Terrorism Cyber 1 Operations with SCO Partners by Peter Wood

Volume XV • Issue 20 • October 19, 2015 In This Issue: In A Fortnight: China Conducts Anti-Terrorism Cyber 1 Operations With SCO Partners By Peter Wood A Tale of Two Documents: US and Chinese Summit Readouts 3 By Bonnie S. Glaser and Hannah Hindel China’s Ethnic Policy Under Xi Jinping 6 By James Leibold Next Focal Point of China’s Stock Market: Earnings—But Can China held its first joint Cyber We Trust the Numbers? 11 By Shaomin Li and Seung Ho Park Counter-Terrorism Exercise, “Xiamen 2015” through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (Source: The Belt, the Road and the PLA 14 By Andrea Ghiselli Xiamen TV) China Brief is a bi-weekly journal of information and analysis covering In a Fortnight Greater China in Eurasia. China Brief is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation, a private non- China Conducts Anti-Terror Cyber profit organization based in Operations With SCO partners Washington D.C. and is edited by Peter Wood. By Peter Wood The opinions expressed in China Brief are solely those of the authors, and do China has conducted its first joint Internet Anti-Terror Exercise (网络 not necessarily reflect the views of The 演习), “Xiamen 2015,” with the members of the Shanghai Cooperation Jamestown Foundation. Organization (SCO) (Xinhua, October 14). Teams from all of the SCO’s member states, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and For comments and questions about Uzbekistan, participated (Xiamen TV, October 14). This follows a China Brief, please contact us at traditional joint counter terrorism exercise, “Counter-Terrorism in [email protected] Central Asia-2015” held in Kyrgyzstan on September 16 (Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure, September 19). -

Ethnic Nationalist Challenge to Multi-Ethnic State: Inner Mongolia and China

ETHNIC NATIONALIST CHALLENGE TO MULTI-ETHNIC STATE: INNER MONGOLIA AND CHINA Temtsel Hao 12.2000 Thesis submitted to the University of London in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London. UMI Number: U159292 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U159292 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h c~5 F . 7^37 ( Potmc^ ^ Lo « D ^(c st' ’’Tnrtrr*' ABSTRACT This thesis examines the resurgence of Mongolian nationalism since the onset of the reforms in China in 1979 and the impact of this resurgence on the legitimacy of the Chinese state. The period of reform has witnessed the revival of nationalist sentiments not only of the Mongols, but also of the Han Chinese (and other national minorities). This development has given rise to two related issues: first, what accounts for the resurgence itself; and second, does it challenge the basis of China’s national identity and of the legitimacy of the state as these concepts have previously been understood.