Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSP Background Variable Documentation in the Philippines

1 ISSP Background Variable Documentation in the Philippines ISSP 2005 Module on Work Orientations III SEX - Sex of respondent National Language English Translation Question no. ISSP1/Sex. Gender of PR ISSP1/Sex. Gender of PR and text Codes/ 1 Male 1 Male Categories 2 Female 2 Female Interviewer Instruction Translation Note Note Construction/Recoding: Country Variable Codes (in translation) SEX 1. Male 1. Male 2. Female 2. Female -not used- 9. No answer, refused Documentation for ISSP background variables © ZA/ZUMA-GESIS 2 AGE - Age of respondent National Language English Translation Question no. ISSP2/AGE. Actual Age ISSP2/AGE. Actual Age and text Interviewer Instruction Translation Note Note Construction/Recoding: (list lowest, highest, and ‘missing’ codes only, replace terms in [square brackets] with real numbers) Country Variable Codes/Construction Rules AGE Construction Codes 18 years old [18] 89 years old [89] 97. No answer, 99. Refused 99. No answer, refused Optional: Recoding Syntax Documentation for ISSP background variables © ZA/ZUMA-GESIS 3 MARITAL - R: Marital status National Language English Translation Question no. ISSP3. Marital Status of PR ISSP3. Marital Status of PR and text 1 May asawa 1 Married 2 Balo 2 Widowed 3 Diborsyado 3 Divorced Codes/ 4 Hiwalay 4 Separated/Married but separated/ not Categories living with legal spouse 5 Walang asawa 5 Single/never married 9 No answer 9 No answer Interviewer Instruction Translation Note Note Construction/Recoding: Country Variable Codes/Construction Rules Marital 1. Married 1. Married, living with legal spouse 2. Widowed 2. Widowed 3. Divorced 3. Divorced 4. Separated/Married but separated/ not living with 4. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

The Sipadan Peace Mission

THE SIPADAN PEACE MISSION An Excerpt from the book, Miracles in Moroland: A Journey of Faith, Love and Courage ( The Inside Story of the Sipadan Hostage Crisis) authored by Sam Smith, published on January 30, 2015 Evangelist Wilde E. Almeda and the JMCIM became involved with the actors of the second major Abu Sayyaf attack on innocents involving Commander Robot’s Sulu faction and the Sipadan hostages. During this crisis, the beloved Pastor Wilde Almeda and the Jesus Miracle Crusade became “house-hold names” when he and his twelve Prayer Warriors went into the dangerous interior of the mountainous region of Jolo Island on a mission of peace to minister to the Moro terrorists and their 21 captives. The list of hostages continued to grow to as many as 38 prisoners as the Abu Sayyaf, motivated by greed and fame, snatched up more and more people who dared to enter the territory controlled by the dreadful Moro insurgents. There have been many misconceptions about Evangelist Wilde Almeda’s Sipadan Peace Mission. The beloved Evangelist was mocked and ridiculed by the media. Some journalists even called him a “firebrand” during the time he spent with the Abu Sayyaf. His life and safety were automatically written off by many Filipino politicians and some elected officials even remarked that if he was “beheaded” then he got what he deserved because he should have calculated the risks. The beloved Evangelist and his Prayer Warriors were even abandoned by many ministers belonging to other Christian congregations. These preachers questioned the Evangelist’s wisdom and judgment from their pulpits during their Sunday sermons. -

Style Guide for the Government Gabay Sa Estilo Para Sa Gobyerno

STYLE GUIDE FOR THE GOVERNMENT GABAY SA ESTILO PARA SA GOBYERNO PRESIDENTIAL COMMUNICATION DEVELOPMENT PRESIDENTIALAND STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS PLANNING OFFICEDEVELOPMENT AND STRATEGIC PLANNING OFFICE RESIDENTIAL C OMMUNIC AT I ON DEVEL OPMENT AND ST RA TEGIC PLANNING OFFI C 1 STYLE GUIDE FOR THE GOVERNMENT GABAY SA ESTILO PARA SA GOBYERNO PRESIDENTIAL COMMUNICATIONS DEVELOPMENT AND STRATEGIC PLANNING OFFICE 2 STYLE GUIDE FOR THE GOVERNMENT Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office ISBN 978-621-95495-0-9 All rights reserved. The content of this publication may be copied, adapted, and redistributed, in whole in part, provided that the material is not used for commercial purposes and that proper attribution be made. No written permission from the publisher is necessary. Some of the images used in this publication may be protected by restrictions from their original copyright owners; please review our bibliography for references used. Published exclusively by The Presidential Communications Developmentand Strategic Planning Office Office of the President of the Philippines 3/F New Executive Building, Malacañan Palace, San Miguel, Manila Website: http://www.pcdspo.gov.ph Email: [email protected] Book design by the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office Published in the Philippines. 3 4 THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES BENIGNO S. AQUINO III President of the Philippines PRESIDENTIAL COMMUNICATIONS DEVELOPMENT AND STRATEGIC PLANNING OFFICE MANUEL L. QUEZON III Undersecretary of Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Officer-in-Charge JAN MIKAEL dL. CO Assistant Executive Secretary Senior Presidential Speechwriter and Head of Correspondence Office JUAN POCHOLO MARTIN B. GOITIA Assistant Secretary Managing Editor, Official Gazette GINO ALPHONSUS A. -

2006 Project Completion Report

GOP-UNDP PROGRAMME FOSTERING DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES – NATIONAL COLLEGE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND GOVERNANCE (UP-NCPAG): IMPLEMENTING PARTNER Programme Management Office Rm. 202, 2nd Floor NCPAG Building, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City Tel No. 928-7331 Telefax 928-7087 2006 PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT 2006 Project Title: Justice Reforms: Sustained Pre-reintegration Referral Services Responsible Party: Bureau of Jail Management and Penology I. Completion Stage Please be informed that as of this time we have already accomplished almost the entire project outputs indicated in our TOR except that of the proper launching of Justice Reforms: Sustained Pre-reintegration Referral Services at Bagong Buhay Rehabilitation Center – Female Dormitory, Cebu City, Region 7 and Davao City Jail – Female Dormitory, Davao City, Region 11. However, efforts were made to orient BJMP personnel coming from the above said Regions in the just concluded two-day seminar held at Femar Garden Resort and Convention Center, Taktak Road, Antipolo City. We are planning to formally launch the project in their respective jails before the year ends. We have already printed three thousand (3000) copies each of the twenty-page Classification and Assessment forms and have published 500 copies of BJMP IPRS Manual. For your perusal, please find the attached list of service providers; names of BJMP Personnel assigned in Pilot Jails, Regional Offices and National Headquarters Office; and the names of the 150 civilian PRS Volunteers. II. Use of BJMP Project Outputs Our recommendations as specified in our Target Outputs for the year 2006 have almost come into complete realization. The IPRS tools which will be used in the Assessment and Classification of inmates – Project beneficiaries - as well as the BJMP IPRS Manual have been printed to serve as guides in the implementation of the program. -

Mindanao: a Beautiful Island Caught Between Rebel Insurgents

www.globalprayerdigest.org GlobalJune 2016 • Frontier Ventures • Prayer35: 6 Digest Mindanao: A Beautiful Island Caught Between Rebel Insurgents 9— Tuboy Subanon On the Run From Muslim Insurgents 18—Don’t Cross the Rebels, Or They Will Burn Your Home 19—Islam and Animism Blend Among the Pangutaran Sama People 25—Tausug People May Not Be Unreached Much Longer! ? 27—Yakans Use Cloth to Protect Newborns from Spirits Editorial JUNE 2016 Feature of the Month RECORDS AND SUBSCRIPTIONS Frontier Ventures Dear Praying Friends, 1605 East Elizabeth Street Pasadena, CA 91104-2721 Every time we cover the Tel: (330) 626-3361 Philippines I feel a little [email protected] guilty. We haven’t prayed EDITOR-IN-CHIEF for the unreached people Keith Carey groups in this country in 15 ASSISTANT EDITOR years. Every June we pray Paula Fern for spiritually needy people WRITERS in Southeast Asia. In this Patricia Depew Patti Ediger issue of the Global Prayer Digest we will concentrate Wesley Kawato on the Muslims of Mindanao, the most southern Ben Kluett Arlene Knickerbocker island in the Philippine nation. Esther Jerome-Dharmaraj Christopher Lane This country is blessed with a large local mission Annabeth Lewis force that is reaching the Muslims on the island. Karen Hightower Ted Proffitt We don’t hear much about all the effort being made Lydia Reynolds by dedicated believers. Jeff Rockwell Jean Smith If we publish too much about their work, we might Jane W. Sveska cause security problems. But we did find out about DAILY BIBLE COMMENTARIES a Filipino pastor, Feliciano “Cris” Lasawang, who Keith Carey David Dougherty gave his life for the gospel last year at the hands of Robert Rutz one of Mindanao’s rebel groups. -

Preview This Book

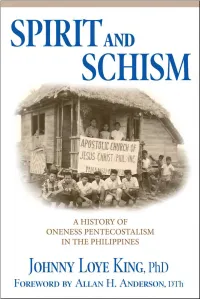

For anyone who loves Apostolic revival and its history, Spirit and Schism by Dr. Johnny King, is a must read. Profoundly researched and exceed- ingly well written, the exciting story of the great Philippine Revival has finally been told. ~Larry L. Booker I had tears in my eyes after reading the thesis. Dr. King has refocused the attention of history to the local Filipino people which has been less talked about or even neglected in other academic works of this na- ture. From the position of this thesis, you can sense the heart Dr. King has for the Filipino people. It is rare and special when a non-Filipino would desire to write a history about the Filipinos from the perspec- tive of a Filipino. ~Yuri Sangueza Dr. Johnny King is a man with something to say. Coming from a world of obscurity and low expectations, he encountered the living Christ and nothing was ever the same. He has risen to become a truly authentic world-class leader. He has positively impacted hundreds of thousands of people around the world. He is a leader, a preacher, a scholar, and a statesman. He is, in a word, what one would define as a man of God. Beyond that, there is nothing higher that can be said of a man. Enjoy his astute scholarship and research in this deeply interesting work. ~Nathaniel J. Wilson Ed.D Mission is at the heart of Pentecostalism. From its inception at Pentecost and subsequent outpourings throughout history, mission has been and remains the normative response of the empowered community of believers. -

Workshop on Faith and Development in Focus: Philippines on January

Workshop on Faith and Development in Focus: Philippines On January 16, 2019, the World Faiths Development Dialogue (WFDD) convened a workshop in Washington, D.C. to discuss preparation of a report on the intersection of development and religion in the Philippines. The meeting was part of WFDD’s ongoing GIZ and PaRD-supported research program that focuses on four countries, including the Philippines. A group of 11 scholars and development experts (listed in Annex 1) contributed their diverse experiences and perspectives. On the evening of January 15, 2019, WFDD hosted a dinner at Executive Director Katherine Marshall’s home where an informal discussion on similar topics took place. Ambassador Anne Derse and Dr. Scott Guggenheim joined the group for dinner, but not the consultation. The discussions helped sharpen and bring new ideas to WFDD’s ongoing analysis on the complex religious dimensions of development issues. The hope is that consultation participants, along with several other individuals who have expressed interested but could not attend, will continue their engagement in this project as an informal advisory group to help guide and offer feedback to WFDD’s work on the Philippines. This note briefly summarizes the content of dialogue that took place at the consultation. To assure a free and open conversation, Chatham House Rule was observed. Therefore, this report does not attribute specific comments or institutional affiliation to any participant in connection to items discussed. A preparatory concept note, see Annex 2, served as an effective point of reference for the group throughout the day. Feedback on the framing of priority issues was positive and constructive, mostly revolving around how to expand on certain topics to reflect more holistically certain sub-fields of development in the Philippines. -

Spirit and Schism: a History of Oneness Pentecostalism in the Philippines

SPIRIT AND SCHISM: A HISTORY OF ONENESS PENTECOSTALISM IN THE PHILIPPINES by Johnny Loye King A Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham Birmingham, UK April 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis presents the history of Oneness Pentecostalism in the Philippines for the first time. It traces the origins, development and current state of this movement. This work will attempt to supply that information, and do so in a manner that recognizes the vital roles of the Filipinos. It argues that schism within the movement was unavoidable due to historical and cultural predispositions of the Filipinos when combined with the paternal methods of the missionaries, and the schismatic nature of Pentecostalism. Important leaders are examined and presented with heretofore-unpublished details of their lives and works, including missionaries and national leaders such as Diamond A. Noble and Wilde Almeda. Some of the many organizations are studied from the perspective of schism and success, and a summary of the entire movement is offered with an analysis as to why people have migrated into it and within it. -

43Rd International Congress on Medieval Studies

43rd International Congress on Medieval Studies 8–11 May 2008 The Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5432 <www.wmich.edu/medieval> 2008 i ii Table of Contents Welcome Letter v Registration vi–vii On-Campus Housing viii Off-Campus Accommodations ix Travel and Parking x Driving to WMU xi Meals xii Facilities xiii Varia xiv Concert xv Film Screenings xvi Plenary Lectures xvii Saturday Night Dance xviii Art Exhibition xix Exhibits Hall xx Exhibitors—2008 xxi Advance Notice—2009 Congress xxii The Congress: How It Works xxiii David R. Tashjian Travel Awards xxiv Gründler and Congress Travel Awards xxv Guide to Acronyms xxvi Richard Rawlinson Center xvii Master’s Program in Medieval Studies xxviii Applying to the MA Program xxix Required Course Work for the MA xxx Faculty Affiliated with the Medieval Institute xxxi Medieval Institute Publications xxxii–xxxiii Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies xxxiv JMIS Editorial Board xxxv The Otto Gründler Book Prize 2009 xxxvi About Western Michigan University xxxvii Endowment and Gift Funds xxxviii 2008 Congress Schedule of Events 1–192 Index of Sponsoring Organizations 193–197 Index of Participants 199–221 List of Advertisers A-1 Advertising A-2–A-59 Maps M-1–M-8 iii iv Dear Colleague: It is a distinct pleasure to invite you to Kalamazoo for the 43rd International Congress on Medieval Studies. As a long-time attendee, and now host, I well know the central role the Congress plays as the premier meeting place of students of the Middle Ages. And each year’s Congress program attests to the abundance of subjects, people, and imaginative approaches to all aspects of the Middle Ages. -

Pentekostalismus, Politik Und Gesellschaft in Den Philippinen

Giovanni Maltese Pentekostalismus, Politik und Gesellschaft in den Philippinen MMaltese_Innenteil_print.pdfaltese_Innenteil_print.pdf 1 224.11.20174.11.2017 009:28:519:28:51 RELIGION IN DER GESELLSCHAFT Herausgegeben von Matthias Koenig, Volkhard Krech, Martin Laube, Detlef Pollack, Hartmann Tyrell, Gerhard Wegner, Monika Wohlrab-Sahr Band 42 ERGON VERLAG MMaltese_Innenteil_print.pdfaltese_Innenteil_print.pdf 2 224.11.20174.11.2017 009:28:569:28:56 Giovanni Maltese Pentekostalismus, Politik und Gesellschaft in den Philippinen ERGON VERLAG MMaltese_Innenteil_print.pdfaltese_Innenteil_print.pdf 3 224.11.20174.11.2017 009:28:569:28:56 Zugl.: Heidelberg, Univ., Diss., 2017 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft [DFG] und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Missionswissenschaft [DGMW] Umschlagabbildung: © Christina Zacke Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Ergon – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2017 Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb des Urheberrechtsgesetzes bedarf der Zustimmung des Verlages. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen jeder Art, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und für Einspeicherungen in elektronische Systeme. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Satz: Matthias Wies, Ergon-Verlag GmbH Umschlaggestaltung: -

Hacia Un Sistema De Clasificación De Grupos Religiosos En América Latina

PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) HACIA UN SISTEMA DE CLASIFICACIÓN DE GRUPOS RELIGIOSOS EN AMÉRICA LATINA, CON UN ENFOQUE ESPECIAL SOBRE EL MOVIMIENTO PROTESTANTE por Clifton L. Holland Versión revisada del 23 de noviembre de 2005 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050, San Pedro, Costa Rica Teléfono: (506) 283-8300; Fax (506) 234-7682 E-correo: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com © Clifton L. Holland, 2004, 2005 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050 San José, Costa Rica Reservados todos los derechos 2 INDICE 1. Presentación 7 2. Hacia una Tipología de Grupos Religiosos por Familias de Iglesias en América Latina 9 3. Un Bosquejo Anotado del Sistema de Clasificación de Grupos Religiosos por Tradiciones Principales, Familias y Subfamilias con Referencia Especial al Contexto Latinoamericano 17 PARTE A: LAS VIEJAS IGLESIAS CRISTIANAS LITURGICAS 17 A1.0 TRADICIÓN LITÚRGICA ORIENTAL 17 A1.10 TRADICIÓN ORTODOXA ORIENTAL 17 A1.11 Patriarcados 18 A1.12 Iglesias Ortodoxas Autocéfalas 18 A1.13 Otras Iglesias Ortodoxas en las Américas 19 A1.14 Otras Iglesias Cismáticas de Tradición Ortodoxa Oriental 19 A1.20 TRADICIÓN ORTODOXA NO CALCEDONIA 19 A1.21 Familia Nestoriana – La Iglesia del Este 20 A1.22 Familia Monofisista 20 A1.23 Familia Copta 21 A1.30 ORGANIZACIONES ORTODOXAS DE INTRAFE 22 A2.0 TRADICIÓN LITÚRGICA OCCIDENTAL 23 A2.1 Iglesia Católica Romana 24 A2.2 Congregaciones Religiosas de la Iglesia Católica Romana 24 A2.3 Iglesias Ortodoxas Autóctonas en Comunión con Roma: Ritos Armenia, Maronita, Melquita, Ucrana,