Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Fecundability in a North American Preconception Cohort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENERGY DRINK Buyer’S Guide 2007

ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 DIGITAL EDITION SPONSORED BY: OZ OZ3UGAR&REE OZ OZ3UGAR&REE ,ITER ,ITER3UGAR&REE -ANUFACTUREDFOR#OTT"EVERAGES53! !$IVISIONOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC4AMPA &, !FTERSHOCKISATRADEMARKOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC 777!&4%23(/#+%.%2'9#/- ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 OVER 150 BRANDS COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR Introduction ADVERTISING EDITORIAL 1123 Broadway 1 Mifflin Place The BEVNET 2007 Energy Drink Buyer’s Guide is a comprehensive compilation Suite 301 Suite 300 showcasing the energy drink brands currently available for sale in the United States. New York, NY Cambridge, MA While we have added some new tweaks to this year’s edition, the layout is similar to 10010 02138 our 2006 offering, where brands are listed alphabetically. The guide is intended to ph. 212-647-0501 ph. 617-715-9670 give beverage buyers and retailers the ability to navigate through the category and fax 212-647-0565 fax 617-715-9671 make the tough purchasing decisions that they believe will satisfy their customers’ preferences. To that end, we’ve also included updated sales numbers for the past PUBLISHER year indicating overall sales, hot new brands, and fast-moving SKUs. Our “MIA” page Barry J. Nathanson in the back is for those few brands we once knew but have gone missing. We don’t [email protected] know if they’re done for, if they’re lost, or if they just can’t communicate anymore. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John Craven In 2006, as in 2005, niche-marketed energy brands targeting specific consumer [email protected] interests or demographics continue to expand. All-natural and organic, ethnic, EDITOR urban or hip-hop themed, female- or male-focused, sports-oriented, workout Jeffrey Klineman “fat-burners,” so-called aphrodisiacs and love drinks, as well as those risqué brand [email protected] names aimed to garner notoriety in the media encompass many of the offerings ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER within the guide. -

Eai LPZZ Rthqi Iopc Acatc Uakc Te^G^ Rghur Ekill >Ngers Run “ Reh V

M m a l l s r i d a h o M o n d a y , AAprin67^979 ------------------------------------ 7 4 tth h year. No. 106^I---------- T w tnrFal E a irth q iu a k ce k ill g o sli[a v ia ^^^^p^W 'Yugosiavav:—there-would bcrmonrdai r awa^M j^HBpi^^B i BELGRADE, Yug'ugoslavja (UPI) — Thehe strongest felt througttouhout Yugoslavia and as far horrifying picture.’’ ears leveled entire villages;s ond spread Germ any, AusAustria, Bulgaria, Albania arim d and Budva anind In Kotor, In the BokaDka Kolorska bay, aboyt 70 percen i.. eaiihguake tn 75 yeai i was de uninhabitable, includlnf' a liosp ^'read death and desilesthictlon along Yugoslavia/ia’s southern Yugoslavlarrlan seismologists said it v ■ * tr *ka bay • further to thUie all houses were made t quake to hitt YlYugoslavia In 75 years, jy.darAVfgftl or knocked dowiwn with 200 patients, officlaflcials said. Several thousand rcsldt Adriatic coast Easter:er Sunday. drialic ^B W W W PPB rch of Kotor were evacuate«ated to a clly soever stadium and It was In the quake-stricken;en area but The eplcententer was placcd In the Adr ■ 9 UUilUUlJ.'lfi^lng hoteljtd s and a 200-year old churc Li_. p^dent.Tlto wa of UIclhJ7and 215 miles soullulh of officials asked for tentsnts and blniikuts for the lhe liomde Ir- escaped unhurt. l o aa I;broadcast to the nation, he sold alw.ui' miles west of -■ • -near!vDubrovnlk. clear he was capital ot Bel{telgrade.. ■>' 200 people had t>een!€n,kUled, but made ll cle vas In the sea,”-said [tltd dlshipted road and rallwajway traffic In the area and ci Army units and specipecial civilian protecHon squads fi "W e were•e Itlucky lhat lhe epicenter wa ephonellnes, electricity and'nd waler supplies, police said all over Uie country■y vwere flowti by helicopters to quoting unoHlcialrw Rlbarlc, director of the LJ»JublJana geological t e l ^ Local govemmenri^ ^ clals said that oboutlUt 150 people Vladim ir Rib Qve had much worse. -

Part I: Analysis of Case 5 1

Part I: Analysis of Case 5 1. What are the strategically relevant components of the global and U.S. beverage industry macro-environment? How do the economic characteristics of the alternative beverage segment of the industry differ from that of other beverage categories? Explain. Market size The beverage market is a large market with the worldwide total market for beverages in 2009 was $1,581.7 billion. The total sale of beverages during 2009 in the US was nearly 458.3 billion gallons; with 48.2 percent of industry sales was from carbonated soft drinks and 29.2 percent of bottle water industry sales. In 2009, the market segment of alternative beverage include sports drinks, flavored or enhanced water, and energy drinks made up 4.0 percent, 1.6 percent, and 1.2 percent of industry sales, respectively. The global market for alternative beverages in the same year was $40.2 billion (12.7 billion liters), while the value of the U.S market for alternative beverages stood at $17 billion (4.2 billion liters). Meanwhile, in Asia-Pacific region, the market for alternative beverages in 2009 was $12.7 billion (6.2 billion liters) and it was $9.1 billion (1.6 billion liters) in the European market. Market growth The dollar value of the global beverage industry had grown at a 2.6 percent annually between 2005 and 2009 and was forecasted to grow at a 2.3 percent between 2010 and 2014. However, this indicator for the alternative beverage industry was much higher. For example, the dollar value of the global market for alternative beverages grew at a 9.8 percent annually between 2005 and 2009, but was expected to slow down to 5.7 percent annually between 2010 and 2014. -

Bottles and Extras Fall 2006 44

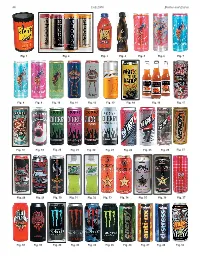

44 Fall 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 32 Fig. 33 Fig. 34 Fig. 35 Fig. 36 Fig. 37 Fig. 38 Fig. 39 Fig. 40 Fig. 42 Fig. 43 Fig. 45 Fig. 46 Fig. 47 Fig. 48 Fig. 52 Bottles and Extras March-April 2007 45 nationwide distributor of convenience– and dollar-store merchandise. Rosen couldn’t More Energy Drink Containers figure out why Price Master was not selling coffee. “I realized coffee is too much of a & “Extreme Coffee” competitive market,” Rosen said. “I knew we needed a niche.” Rosen said he found Part Two that niche using his past experience of Continued from the Summer 2006 issue selling YJ Stinger (an energy drink) for By Cecil Munsey Price Master. Rosen discovered a company named Copyright © 2006 “Extreme Coffee.” He arranged for Price Master to make an offer and it bought out INTRODUCTION: According to Gary Hemphill, senior vice president of Extreme Coffee. The product was renamed Beverage Marketing Corp., which analyzes the beverage industry, “The Shock and eventually Rosen bought the energy drink category has been growing fairly consistently for a number of brand from Price Master. years. Sales rose 50 percent at the wholesale level, from $653 million in Rosen confidently believes, “We are 2003 to $980 million in 2004 and is still growing.” Collecting the cans and positioned to be the next Red Bull of bottles used to contain these products is paralleling that 50 percent growth coffee!” in sales at the wholesale level. -

Science, Manufacture, and Marketing of Red Bull and Other Energy Drinks Zeno Yeates, ‘10

No Bull: Science, Manufacture, and Marketing of Red Bull and Other Energy Drinks Zeno Yeates, ‘10 (Photo by Yohan Moon) Yohan by (Photo Zeno smells bad. bad. smells Zeno he increasing prevalence of energy drinks over the The ingredients were explicitly listed on the can itself, and neither Tpast decade is a phenomenon that cannot simply be trademark nor patent existed to protect its formula; hence, Red dismissed as a passing obsession. What began with the advent of Bull was born [3]. Red Bull in 1984 has evolved into a colossus of different brands Careful observation of any university library will reveal the claiming anything from sharpened mental acuity to enhanced undeniable popularity of iPods and Red Bulls – the arsenal for athletic performance. Austrian-born Red Bull founder and CEO the true titan of academic endeavor confronting a full night of Dietrich Mateschitz relies on the younger generation for his sales intellectual tribulation. Nevertheless, some conjecture whether base, exploiting the teenage drive for risk-taking and adventure Red Bull’s buzz serves only to distract the active mind in the using dramatic product names, draconian logos, and sponsorship same way that prolonged auditory stimulation seems to. The of extreme sporting events [1]. Predictably, a multitude of most immediate answer is given on the container itself, which competitors have followed suit, introducing similar concoctions specifically claims to improve performance in times of elevated with dicey names such as Cocaine, Dare Devil, Pimp Juice, stress or strain, increase endurance, increase reaction speed, and Venom, and Monster. However, none of the claims of enhanced stimulate metabolism [4]. -

Caffeine Content in Foods and Beverages - Uptodate

16/02/2020 Caffeine content in foods and beverages - UpToDate Official reprint from UpToDate® © 2020 UpToDate, Inc. e/ou seus afiliados. Todos os direitos reservados.www.uptodate.com Caffeine content in foods and beverages Coffees Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg Coffee, brewed 8 (235) 133 (range: 102 to 200) Coffee, generic instant 8 (235) 93 (range: 27 to 173) Coffee, generic decaffeinated 8 (235) 5 (range: 3 to 12) Espresso 1 (30) 40 (range: 30 to 90) Espresso decaffeinated 1 (30) 4 Teas Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg Tea, brewed 8 (235) 53 (range: 40 to 120) Arizona Iced Tea, black 16 (470) 32 Arizona Iced Tea, green 16 (470) 15 Nestea 12 (355) 26 Snapple, Just Plain Unsweetened 16 (470) 18 Snapple, Kiwi Teawi 16 (470) 10 Snapple, Lemon, Peach, or Raspberry 16 (470) 42 Starbucks Tazo Chai Tea Latte (Grande) 16 (470) 100 Soft drinks Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg FDA official limit for cola and pepper soft 12 (355) 71 drinks 7-Up, regular or diet 12 (355) 0 Barq's Diet Root Beer 12 (355) 0 Barq's Root Beer 12 (355) 22 Coke, regular or diet 12 (355) 35 to 47 Dr. Pepper, regular or diet 12 (355) 42 to 44 Fanta, all flavors 12 (355) 0 Fresca, all flavors 12 (355) 0 Jolt Cola 12 (355) 72 Mellow Yellow 12 (355) 53 Mountain Dew, regular or diet 12 (355) 54 (20 oz = 90) Mountain Dew MDX, regular or diet 12 (355) 71 (20 oz = 118) Mug Root Beer, regular or diet 12 (355) 0 Pepsi, regular or diet 12 (355) 36 to 38 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image/print?csi=dc8cf830-1b2b-4faa-9f01-bf4cf6c3967a&source=contentShare&imageKey=OBGYN%2F79304 -

Determination of Caffeine in Beverages

CHM250 HPLC-1 LAB Determination of Caffeine in Beverages Introduction This experiment provides an introduction to the application of High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to the solution of complex analytical problems. Cola type drinks, coffee, and tea all are complex chemical systems that contain varying amounts of caffeine. The amount of caffeine present in these beverages can be determined by HPLC. An isocratic HPLC using a reverse phase C18 column is used in this experiment. The mobile phase is 50% by volume methanol in water prepared from ultra-pure water and HPLC grade methanol containing 1% acetic acid. With the instrument that is being used, it is not necessary to degas the water or the methanol. Care should be taken not to aerate solutions when pouring them. The beverage samples will be filtered to remove any insoluble material. In reverse phase HPLC the mobile phase is polar and the stationary phase in non-polar. When a sample is injected into the instrument, the mobile phase moves it through the column. Molecules in the sample that are polar interact more strongly with the mobile phase and elute from the column first. Non-polar molecules interact more strongly with the stationary phase and elute from the column last. As molecules elute from the column, they are detected, and a peak is recorded in chromatogram. The identity of a peak can be found by comparing its retention time (the time that it eluted from the column) to the retention time of known compounds. Identical substances will have identical retention times. The area of the peak is also important as peak area is proportional to the concentration of that particular species in the sample. -

Health Services News

HEALTH SERVICES NEWS FALL 2019 Flu vaccines are here and available as of October 1st-call for an appointment 201-684-7536. Hello All, Health Services would like to welcome all new and returning students to campus for the beginning of a new semester! For those of you not familiar with Health Services, a few points as a way to introduce ourselves. Health Services is a part of the same department as Counseling Services, but we are in a different location. Our office is in the gray building at the south entrance to the college, where the new solar panels have been installed. During fall and spring semester, we are open Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. During the summer, we are open Monday through Thursday from 8 a.m. to 5:15 p.m. There are days when we are busy, typically once the cold and flu season begins, and ask students to please call and make an appointment before coming to the office. This allows us to see students without a long wait and prevents a student from walking to the office only to be told to come back later due to no available appointments at that time. Our main extension is 7536. What We Do: We see students for a variety of illnesses including colds and flu, allergic reactions, skin problems, asthma, infections, STD testing, allergy injections and women’s’ health issues. We also administer influenza vaccines and do tuberculosis testing. Hyacinth, a community provider of HIV testing and counseling, will be on campus twice a month. -

Energy Drinks – What You Don't Know

Energy Drinks – What You Don’t Know The US energy drink business is a yearly $5.4 billion industry. Energy drinks are marketed to many students who may need “wings” to help stay awake during class or study. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not approve or review energy drinks since they are marketed as dietary supplements. Therefore, many drink claims have not been proven, the amount of added ingredients is neither standardized nor identified on the label and their safety is not known. The best way to feel energetic remains eating healthy foods, regular physical activity, and getting enough sleep. Common “Energy” Ingredients Caffeine—a chemical compound that stimulates the central nervous system. Safe in smaller doses, caffeine in larger amounts may cause blood pressure spikes, headaches, nausea, sleeplessness or tremors. Caffeine in larger doses will act as a diuretic and may lead to dehydration. Sugar—the same thing as sucrose, glucose, fructose, corn syrup or high fructose corn syrup. Sugar is known to give an instant boost but after very little time will cause a crash in both energy and alertness. Additionally, sugar has 4 calories per gram, a 8.3 ounce Red Bull has 27 grams of sugar; that’s 108 non‐nutritional calories! Guarana—a South American plant that produces seeds with 4‐5% caffeine content, while a coffee bean has the caffeine content of 1‐2%. Guarana in a 16‐ounce energy drink ranges from 1.4 mg to as much as 300 mg. It is unclear how much guarana is in each drink because many companies do not list a milligram amount. -

2005 Annual Report

oca-Cola Bottling Co. Consolidated is the C second largest Coca-Cola bottler in the United States. We are a leader in the manufac- turing, marketing and distribution of soft drinks. With corporate offi ces in Charlotte, N.C., we have operations in 11 states, primarily in the Southeast. Th e Company has one of the highest per capita soft drink consumption rates in the world and manages bottling territories with a consumer base of 18.6 million people. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. Consolidated is listed on the NASDAQ National Market System under the symbol COKE. This annual report is printed on recycled paper. Financial Summary* Fiscal Year In Thousands (Except Per Share Data) 2005 2004 2003 Net sales $1,380,172 $1,267,227 $1,220,403 Gross margin 627,763 607,761 591,323 Income before income taxes 38,752 36,550 38,060 Income taxes 15,801 14,702 7,357 Net income 22,951 21,848 30,703 Basic net income per share $ 2.53 $ 2.41 $ 3.40 Diluted net income per share $ 2.53 $ 2.41 $ 3.40 * The financial information in this Summary Annual Report was derived from and should be read in conjunction with the audited consolidated financial statements and notes thereto and management's discussion and analysis of the financial condition and results of operations, which are included in the Company's Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended January 1, 2006. The fiscal years presented are the 53-week period ended January 2, 2005, and the 52-week periods ended January 1, 2006, and December 28, 2003. -

Source of Information

Source of information: http://www.americanathleticinstitute.org/response-ability/?cat=4 There are no regulations regarding the amount of caffeine in energy drinks “Energy drinks ‘need caffeine alert on cans’”, is the headline in the Daily Mail. The newspaper reports on a study that looked at 28 energy drinks and showed some have up to 14 times the caffeine content of a can of cola. Doctors have warned that these drinks should “carry health warnings”, so young people do not overdose on caffeine, says the newspaper. The study is a review of the history and regulatory background of caffeine‐based energy drinks in the US, including some of the “top selling US energy drinks”, which are also marketed in the UK. The authors discuss the potential for caffeine dependence and withdrawal problems that could be associated with energy drinks. This study did not measure the caffeine content of the drinks directly and did not investigate directly the effect of caffeine intake from these drinks on the body. The problems of toxicity and dependence that can follow caffeinated drink consumption, as discussed by the authors, will need further investigation before there is any proposed change in regulation. Where did the story come from? Dr Chad J. Reissig and colleagues from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the John Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, US, carried out this research. The authors declare conflicts of interests in that they own stock in soft drinks companies. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. It was published in the peer‐reviewed medical journal: Drug and Alcohol Dependence. -

22 the PRODUCT Coca-Cola. It's a Simple Idea, Really. Drinking a Coke

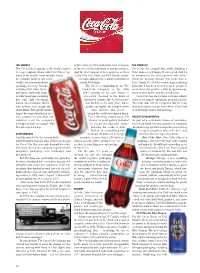

THE MARKET of Diet Coke in 1982 marked the first extension THE PRODUCT The Coca-Cola Company is the world’s largest of the Coca-Cola trademark to another product. Coca-Cola. It’s a simple idea, really. Drinking a beverage company. Along with Coca-Cola, recog- And the development of new products, such as Coke makes people happy. It tastes good. And it’s nized as the world’s most valuable brand, Coca-Cola Zero, Vault, and Full Throttle contin- an invitation to live on the positive side of life. the company markets four of the ues today, adding to the company’s portfolio of That’s the message behind “The Coke Side of world’s top-five nonalcoholic nearly 400 brands. Life,” brand Coca-Cola’s overarching marketing sparkling beverage brands, The latest accomplishment for The platform. It has been created to invite people to including Diet Coke, Fanta, Coca-Cola Company is the May create their own positive reality, be spontaneous, and Sprite, and a wide range 2007 opening of the new World of listen to their hearts, and live in full color. of other beverages, including Coca-Cola. Located in the heart of Coca-Cola has always been at its best when it diet and light beverages, downtown Atlanta, the 92,000-square- reflects the simple, optimistic moments in life. waters, juices and juice drinks, foot facility is the only place where The Coke Side of Life recognizes that the most teas, coffees, and energy and people can explore the complete story universal experiences are those where Coca-Cola sports drinks.