Caffeine, Public Health, and the Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Fecundability in a North American Preconception Cohort

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Intake of Sugar-sweetened Beverages and Fecundability in a North American Preconception Cohort Elizabeth E. Hatch,a Amelia K. Wesselink,a Kristen A. Hahn,a James J. Michiel,a Ellen M. Mikkelsen,b Henrik Toft Sorensen,b Kenneth J. Rothman,a,c and Lauren A. Wisea Background: Dietary factors, including sugar-sweetened beverages, pproximately 10%–15% of North American couples may have adverse effects on fertility. Sugar-sweetened beverages Aexperience infertility, defined as the inability to con- 1 were associated with poor semen quality in cross-sectional studies, ceive after 12 or more months of attempting pregnancy. and female soda intake has been associated with lower fecundability Both female and male factors contribute to infertility, with in some studies. estimates of 39% of cases due to a female factor alone, 20% Methods: We evaluated the association of female and male sugar- to a male factor, 33% to both male and female factors, and sweetened beverage intake with fecundability among 3,828 women 8% with unknown cause.2 Thus, identifying modifiable fac- planning pregnancy and 1,045 of their male partners in a North Ameri- tors in both partners that can improve fertility (e.g., diet) can prospective cohort study. We followed participants until pregnancy could help couples avoid expensive and stressful fertility or for up to 12 menstrual cycles. Eligible women were aged 21–45 treatments. (male partners ≥21), attempting conception for ≤6 cycles, and not using fertility treatments. Participants completed a comprehensive The amount of added sugar in the American diet 3 baseline questionnaire, including questions on sugar-sweetened bever- increased by 19% between 1970 and 2005. -

ENERGY DRINK Buyer’S Guide 2007

ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 DIGITAL EDITION SPONSORED BY: OZ OZ3UGAR&REE OZ OZ3UGAR&REE ,ITER ,ITER3UGAR&REE -ANUFACTUREDFOR#OTT"EVERAGES53! !$IVISIONOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC4AMPA &, !FTERSHOCKISATRADEMARKOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC 777!&4%23(/#+%.%2'9#/- ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 OVER 150 BRANDS COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR Introduction ADVERTISING EDITORIAL 1123 Broadway 1 Mifflin Place The BEVNET 2007 Energy Drink Buyer’s Guide is a comprehensive compilation Suite 301 Suite 300 showcasing the energy drink brands currently available for sale in the United States. New York, NY Cambridge, MA While we have added some new tweaks to this year’s edition, the layout is similar to 10010 02138 our 2006 offering, where brands are listed alphabetically. The guide is intended to ph. 212-647-0501 ph. 617-715-9670 give beverage buyers and retailers the ability to navigate through the category and fax 212-647-0565 fax 617-715-9671 make the tough purchasing decisions that they believe will satisfy their customers’ preferences. To that end, we’ve also included updated sales numbers for the past PUBLISHER year indicating overall sales, hot new brands, and fast-moving SKUs. Our “MIA” page Barry J. Nathanson in the back is for those few brands we once knew but have gone missing. We don’t [email protected] know if they’re done for, if they’re lost, or if they just can’t communicate anymore. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John Craven In 2006, as in 2005, niche-marketed energy brands targeting specific consumer [email protected] interests or demographics continue to expand. All-natural and organic, ethnic, EDITOR urban or hip-hop themed, female- or male-focused, sports-oriented, workout Jeffrey Klineman “fat-burners,” so-called aphrodisiacs and love drinks, as well as those risqué brand [email protected] names aimed to garner notoriety in the media encompass many of the offerings ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER within the guide. -

Somebody Told Me You Died

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2020 Somebody Told Me You Died Barry E. Maxwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Nonfiction Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maxwell, Barry E., "Somebody Told Me You Died" (2020). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11606. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11606 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOMEBODY TOLD ME YOU DIED By BARRY EUGENE MAXWELL Associate of Arts in Creative Writing, Austin Community College, Austin, TX, 2015 Bachelor of Arts with Honors, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, 2017 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Nonfiction The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2020 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg Dean of The Graduate School Judy Blunt Director, Creative Writing Department of English Kathleen Kane Department of English Mary-Ann Bowman Department of Social Work Maxwell, Barry, Master of Fine Arts, Spring 2020 Creative Writing, Nonfiction Somebody Told Me You Died Chairperson: Judy Blunt Somebody Told Me You Died is a sampling of works exploring the author’s transition from “normal” life to homelessness, his adaptations to that world and its ways, and his eventual efforts to return from it. -

Caffeine- the Legal Addiction

Caffeine- the legal addiction By Stephanie Palmer Whether your drink of choice is Monster or Rockstar, Jolt or Bawls, you may want to read this before partaking in another can of your favorite boost and /or fix of caffeine. Energy drink companies claim a lot of things when they advertise their products, such as, alertness, improved cognition, increased energy, and so on. However upon researching the information and claims, I found more adverse effects than benefits. First though I thought you might like to hear that you are not alone in your choice to drink energy drinks, because, well, they are everywhere. With over 800 different kinds to choose from and vending machines and retail places all over campus providing a constant supply of caffeine, they are hard to avoid. But sometimes following the crowd isn’t necessarily a good thing. Based on one study I found, 51% of college student reported drinking one or more energy drinks per month. Of that 51%, slightly more were female. Close to three quarters of that 51% drank energy drinks that contained sugar. According to this study there were 6 main reasons for consuming energy drinks: Lack of sleep or insufficient sleep, to increase energy, using at parties in combination with alcohol, studying or finishing a project, driving for long periods of time, and to treat a hangover. 16-20% of the students surveyed consumed energy drinks for at least 1-5 of the situations, and 7% consumed them for all six. As the number of situations increased so did the amount of consumed drinks. -

Empty Beer Bottle/Can/Pet Container Returns

September 7, 2020 TO: ALL HOTEL BEER VENDORS/LIQUOR VENDORS APPROVED TO SELL PRIVATELY DISTRIBUTED BEER RE: EMPTY BEER BOTTLE/CAN/PET CONTAINER RETURNS Attached are lists of beer products sold in the province of Manitoba. All containers carry a 10¢ refundable deposit with the exception of containers 2 litres or larger which are 20¢. Note: Please continue to follow any Covid-19 protocols you have in place. These lists are also available at www.mbllpartners.ca. As per Regulation 68/2014 of Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Board Regulation to The Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation Act: ‘1 Unless authorized by the corporation, a retail beer vendor must (a) accept empty beer bottles or beer cans from products purchased in Manitoba on which a refundable deposit has been paid; Empty containers are to be sorted by distributor. As a reminder, WETT Sales & Distribution Inc. is responsible for the pick-up of all containers sold only through MBLL Liquor Marts and Liquor Vendors. Hotel Beer Vendors/Vendors approved to sell Privately Distributed Beer are required to sort by distributor in the usual manner. If you are unsure if the product has been sold in Manitoba and is eligible for a refund, in the interest of customer service and if the quantities are reasonable, please accept them from the customer and return them through WETT Sales in the normal manner. Should you have any questions, please email [email protected] Yours truly, Laurie Kennedy Manager, Supply Chain Administration 1555 Buffalo Place Winnipeg MB R3T 1L9 T 204 957 -

Pricebook Creator

Table of Contents - Case Beer DOMESTIC 1 LAGUNITAS - CALIFORNIA 15 2 TOWNS CIDER - OREGON 30 CAMO 1 LEINENKUGEL - WISCONSIN 16 HARD CIDER GLUTEN FREE - PAB 31 COLT 45 1 LOST COAST - CALIFORNIA 16 CASCADIA HARD SELTZER - OREGON 31 COORS BANQUET 1 MAC & JACK - WASHINGTON 16 IMPORTS - CRAFT 31 COORS LIGHT 1 MAD RIVER - CALIFORNIA 16 OMMEGANG - NEW YORK 19 COORS NA 1 MAGIC HAT - VERMONT 17 IMPORTS - IMPORT 31 EARTHQUAKE 1 MARATHON BREWING - MASS 17 AMSTEL - HOLLAND 31 GENESEE 1 MENDOCINO - CALIFORNIA 17 ASAHI - JAPAN 31 GENESEE CREAM 1 MIGRATION - OREGON 17 BEERS OF MEXICO - MEXICO 31 GENESEE ICE 1 MISSION BREWERY - CALIFORNIA 17 BIRRA MORETTI - ITALY 31 HAMMS 1 MISSION ST - CALIFORNIA 17 BITBURGER - GERMANY 31 HENRY WEINHARD BLUE BOAR ALE 2 NEW BELGIUM - COLORADO 17 BOHEMIA - MEXICO 31 HENRY WEINHARD PRIVATE RESERVE 2 NEW HOLLAND - MICHIGAN 18 BUCKLER NA - HOLLAND 31 ICEHOUSE 2 NGB - WISCONSIN 18 CARTA BLANCA - MEXICO 31 KEYSTONE 2 NORTH COAST - CALIFORNIA 18 CHANG BEER - THAILAND 32 KEYSTONE ICE 2 OAKSHIRE BREWING - OREGON 19 CHIMAY - BELGIUM 32 KEYSTONE LIGHT 2 ODIN BREWING - WASHINGTON 19 CHOUFFE - BELGIUM 32 LITE 2 OMMEGANG - NEW YORK 19 CORONA - MEXICO 32 MICKEY ICE 2 PORTLAND BREW - OREGON 20 CORONA FAMILAR - MEXICO 32 MICKEY MALT 2 PYRAMID - OREGON 20 CORONA LIGHT - MEXICO 32 MILLER GENUINE DRAFT 2 ROGUE - OREGON 20 CORONA PREMIER - MEXICO 32 MILLER HIGH LIFE 3 ROGUE XS - OREGON 21 DOS EQUIS - MEXICO 33 MILLER 64 3 SAINT ARCHER - CALIFORNIA 21 DUVEL - BELGIUM 33 MILWAUKEE BEST 3 SAM ADAMS - MASSACHUSETTS 21 FOSTERS - AUSTRALIA 33 -

Eai LPZZ Rthqi Iopc Acatc Uakc Te^G^ Rghur Ekill >Ngers Run “ Reh V

M m a l l s r i d a h o M o n d a y , AAprin67^979 ------------------------------------ 7 4 tth h year. No. 106^I---------- T w tnrFal E a irth q iu a k ce k ill g o sli[a v ia ^^^^p^W 'Yugosiavav:—there-would bcrmonrdai r awa^M j^HBpi^^B i BELGRADE, Yug'ugoslavja (UPI) — Thehe strongest felt througttouhout Yugoslavia and as far horrifying picture.’’ ears leveled entire villages;s ond spread Germ any, AusAustria, Bulgaria, Albania arim d and Budva anind In Kotor, In the BokaDka Kolorska bay, aboyt 70 percen i.. eaiihguake tn 75 yeai i was de uninhabitable, includlnf' a liosp ^'read death and desilesthictlon along Yugoslavia/ia’s southern Yugoslavlarrlan seismologists said it v ■ * tr *ka bay • further to thUie all houses were made t quake to hitt YlYugoslavia In 75 years, jy.darAVfgftl or knocked dowiwn with 200 patients, officlaflcials said. Several thousand rcsldt Adriatic coast Easter:er Sunday. drialic ^B W W W PPB rch of Kotor were evacuate«ated to a clly soever stadium and It was In the quake-stricken;en area but The eplcententer was placcd In the Adr ■ 9 UUilUUlJ.'lfi^lng hoteljtd s and a 200-year old churc Li_. p^dent.Tlto wa of UIclhJ7and 215 miles soullulh of officials asked for tentsnts and blniikuts for the lhe liomde Ir- escaped unhurt. l o aa I;broadcast to the nation, he sold alw.ui' miles west of -■ • -near!vDubrovnlk. clear he was capital ot Bel{telgrade.. ■>' 200 people had t>een!€n,kUled, but made ll cle vas In the sea,”-said [tltd dlshipted road and rallwajway traffic In the area and ci Army units and specipecial civilian protecHon squads fi "W e were•e Itlucky lhat lhe epicenter wa ephonellnes, electricity and'nd waler supplies, police said all over Uie country■y vwere flowti by helicopters to quoting unoHlcialrw Rlbarlc, director of the LJ»JublJana geological t e l ^ Local govemmenri^ ^ clals said that oboutlUt 150 people Vladim ir Rib Qve had much worse. -

Part I: Analysis of Case 5 1

Part I: Analysis of Case 5 1. What are the strategically relevant components of the global and U.S. beverage industry macro-environment? How do the economic characteristics of the alternative beverage segment of the industry differ from that of other beverage categories? Explain. Market size The beverage market is a large market with the worldwide total market for beverages in 2009 was $1,581.7 billion. The total sale of beverages during 2009 in the US was nearly 458.3 billion gallons; with 48.2 percent of industry sales was from carbonated soft drinks and 29.2 percent of bottle water industry sales. In 2009, the market segment of alternative beverage include sports drinks, flavored or enhanced water, and energy drinks made up 4.0 percent, 1.6 percent, and 1.2 percent of industry sales, respectively. The global market for alternative beverages in the same year was $40.2 billion (12.7 billion liters), while the value of the U.S market for alternative beverages stood at $17 billion (4.2 billion liters). Meanwhile, in Asia-Pacific region, the market for alternative beverages in 2009 was $12.7 billion (6.2 billion liters) and it was $9.1 billion (1.6 billion liters) in the European market. Market growth The dollar value of the global beverage industry had grown at a 2.6 percent annually between 2005 and 2009 and was forecasted to grow at a 2.3 percent between 2010 and 2014. However, this indicator for the alternative beverage industry was much higher. For example, the dollar value of the global market for alternative beverages grew at a 9.8 percent annually between 2005 and 2009, but was expected to slow down to 5.7 percent annually between 2010 and 2014. -

CIR WP Energy Drinks 0113 CIR WP Energy Drinks 0113 1/28/13 2:19 PM Page 1

CIR_WP_Energy Drinks_0113_CIR_WP_Energy Drinks_0113 1/28/13 2:19 PM Page 1 CIRCADIAN ® White Paper ENERGY DRINKS The Good, the Bad, and the Jittery Jena L. Pitman-Leung, Ph.D., Becca Chacko, & Andrew Moore-Ede 2 Main Street, Suite 310 Stoneham, MA 02180 USA tel 781-439-6300 fax 781-439-6399 [email protected] www.circadian.com CIR_WP_Energy Drinks_0113_CIR_WP_Energy Drinks_0113 1/28/13 2:19 PM Page 2 ENERGY DRINKS Introduction Energy drinks have become the new “go-to” source of caffeine in our 24/7 society, particularly for young people. Available nearly everywhere, affordable and conveniently packaged, energy drinks represent an apparently simple solution to the worldwide exhaustion epidemic. Yet despite their widespread consumption and popularity - sales in the United States reached over $10 billion in 2012 - many questions still remain about their safety and efficacy (Meier, January 2013). To start with, most energy drinks contain ingredients that consumers are not familiar with, and that haven’t been studied for safe consumption in a laboratory environment. The goal of this whitepaper is to provide background information on what makes energy drinks different from other common sources of caffeine, examine the ingredients that give energy drinks their “boost”, and identify best consumption practices and potential safety issues.* I. What Are Energy Drinks Anyway? You might say that energy drinks are the older, stronger, jock brother of caffeinated soft drinks. They share some similarities – both are typically carbonated, contain caffeine and sugar, and are available everywhere. However, the biggest difference between energy drinks and sodas is how they are classified by the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA). -

Sheet1 Page 1 Name of Drink Caffeine (Mg) 5 Hour Energy 60

Sheet1 Name of drink Size (mL) Caffeine (mg) 5 Hour Energy 60 Equivalent of a cup of coffee Amp Energy (Original) 710 213 Amp Energy (Original) 473 143 Amp Energy Overdrive 473 142 Amp Energy Re-Ignite 473 158 Amp Energy Traction 473 158 Bawls Guarana 473 103 Bawls Guarana Cherry 473 100 Bawls Guarana G33K B33R 296 80 Bawls Guaranexx Sugar Free 473 103 Beaver Buzz Black Currant Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Citrus Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Green Machine Energy 473 200 Big Buzz Chronic Energy 473 200 BooKoo Energy Citrus 710 360 BooKoo Energy Wild Berry 710 360 Cheetah Power Surge Diet 710 None? Frank's Energy Drink 500 160 Frank's Energy Drink Lime 250 80 Frank's Energy Drink Pineapple 250 80 Full Throttle Unleaded 473 141 Hansen's Energy Pro 246 39 Hardcore Energize Bullet Blue Rage 85.7 300 Hype Energy Pro (Special Edition) 355 114 Hype Energy MFP 473 151 Inked Chikara 473 151 Inked Maori 473 151 Jolt Endurance Shot 60 200 Jolt Orange Blast 695 220 Lost (Original) 473 160 Lost Five-O 473 160 Mini Thin Rush (6 Hour) 60 200 Monster (Original) 710 246 Monster Assault 473 164 Monster Energy (Original) 473 170 Monster Khaos 710 225 Monster Khaos 473 150 Monster M-80 473 164 Monster MIXXD 473 Monster Reduced Carb 473 140 NOS (Original) 473 200 NOS (Original)(Bottle) 650 343 NOS Fruit Punch 473 246.35 Premium Green Tea Energy 355 119 Premium Iced Tea Energy 355 102 Premium Pink Energy 355 120 Red Bull 250 80 Red Bull 355 113.6 Page 1 Sheet1 Red Rain 250 80 Rocket Shot 54 50 Rockstar Burner 473 160 Rockstar Burner 710 239 Rockstar Diet 473 160 -

Bottles and Extras Fall 2006 44

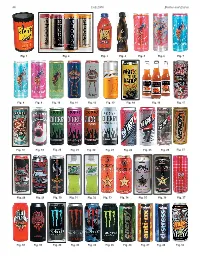

44 Fall 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 32 Fig. 33 Fig. 34 Fig. 35 Fig. 36 Fig. 37 Fig. 38 Fig. 39 Fig. 40 Fig. 42 Fig. 43 Fig. 45 Fig. 46 Fig. 47 Fig. 48 Fig. 52 Bottles and Extras March-April 2007 45 nationwide distributor of convenience– and dollar-store merchandise. Rosen couldn’t More Energy Drink Containers figure out why Price Master was not selling coffee. “I realized coffee is too much of a & “Extreme Coffee” competitive market,” Rosen said. “I knew we needed a niche.” Rosen said he found Part Two that niche using his past experience of Continued from the Summer 2006 issue selling YJ Stinger (an energy drink) for By Cecil Munsey Price Master. Rosen discovered a company named Copyright © 2006 “Extreme Coffee.” He arranged for Price Master to make an offer and it bought out INTRODUCTION: According to Gary Hemphill, senior vice president of Extreme Coffee. The product was renamed Beverage Marketing Corp., which analyzes the beverage industry, “The Shock and eventually Rosen bought the energy drink category has been growing fairly consistently for a number of brand from Price Master. years. Sales rose 50 percent at the wholesale level, from $653 million in Rosen confidently believes, “We are 2003 to $980 million in 2004 and is still growing.” Collecting the cans and positioned to be the next Red Bull of bottles used to contain these products is paralleling that 50 percent growth coffee!” in sales at the wholesale level. -

Caffeine What You Need to Know.Pub

Caffeine: Sneaky Caffeine Pitfalls What You Need to Know Most beverages are served in large portion sizes. There can be multiple servings in a single container! Many en- ergy drinks recommend having multiple containers per How Caffeine day. When that container is already huge, your caffeine Affects Your consumption can go through the roof! Body Be Smart About Caffeine Caffeine has long been Green tea, decaffeinated tea or coffee, and diet soda are known to elevate blood the best bets in terms of caffeine content and calories. pressure acutely. A well- If you are caffeine sensitive or if your health profession- designed study examined al advises that you skip caffeine, be aware that decaf- the impact of 250 mg of feinated coffee and tea do contain some caffeine. caffeine in subjects who Make coffee with filters. This is better for your heart – consumed no coffee in the previous 3 weeks. Researchers found that the av- coffee made without filters has been shown to raise cho- erage blood pressure increased by 14/10 mmHg lesterol. one hour after the caffeine was consumed. Coffee raises blood pressure by both increasing vasocon- striction and reducing vasodilation. A clinical tri- A Note About Energy Shots al of patients with hypertension who stopped Some energy drinks come in tiny, caffeine-rich contain- drinking coffee did find a significant drop in ers called “shots.” 5 Hour Energy, for example, contains blood pressure, at least in the short-term. 138 milligrams of caffeine in just two ounces. It’s also low in calories. The manufacturers recommend taking Typical Amounts of Caffeine two shots per day, spaced apart.