Crossing Crossing Conceptual Boundaries III School of Law And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedian Jimmy Tarbuck

When I was live on Sky News recently, a lady asked me if I was Roy Hudd. It was hilarious! kids, Cheryl, 56, and Liza, 53, and our DEFINITE five grandchildren – at La Famiglia, Chelsea. I always have the seafood pasta. Then home to Surrey to kip! The happiest moment you will cherish forever… The births of my kids, but ARTICLE marrying Pauline in 1959 was special. We ask a celebrity a set of devilishly Bobby Campbell was my best man. The saddest time that shook your probing questions – and only accept world… When my mother Fanny died from stomach cancer in 1970, aged 72. THE definitive answer. This week it’s I thought my parents were immortal. veteran comedian Jimmy Tarbuck The unfulfilled ambition that contin- ues to haunt you… To score the win- The prized possession you value The book that ning goal for Liverpool in the FA Cup above all others… A tweed cap given holds an ever- Final. I’m 78 but there’s still time... to me by Ronnie Corbett before he lasting reso - The philosophy that underpins your died in 2016. I wear it all the time. He nance… The Best Of life… Never hurry, never worry, and was a delightful, loyal friend. A great Henry Longhurst, a stop and smell the flowers sometimes. talent who should’ve been knighted. compilation of his arti- The order of service at your funeral… The biggest regret you wish you could cles about golf. It’s full of I’d be carried in to You’ll Never Walk amend… I wish I’d been more patient terrific humour and advice. -

East Bristol Auctions

East Bristol Auctions Entertainment Memorabilia & Autographs - Worldwide Postage, Packing & Delivery Available On All Items 1 Hanham Business Park Memorial Road Bristol LIVE BROADCAST AUCTION ONLY - NO IN PERSON BS15 3JE BIDDING - VIEWING BY APPOINTMENT ONLY FOR SPECIFIC United Kingdom LOTS - FACEBOOK LIVE VIEWING EVENT JUNE 18TH 11AM Started 19. Jun 2020 09:55 BST Lot Description Star Wars ; Return Of The Jedi (1983) - rare original British Quad film poster, with artwork by Josh Kirby depicting the main characters, 1 overshadowed by Darth Vader with The Death Star to the corner. 20th Century Fox. Folded. Approx 30x40". Rare poster from the most famous sci-fi franchise in the w ...[more] Billy Smart's Circus - Clapham Common, London - a rare original believed 1960's (possibly earlier) Circus advertising poster. Printed in 2 yellow, blue and red. ' Oct 18th to Nov. 13th ', with pricing and entry information to bottom. Folded, with some wear as seen. Measures approx; 75x51cm. Rare poste ...[more] The Beatles - a rare full set of original 1960's The Beatles ' gumball ' type plastic finger rings. Each of a differing colour, and each ring 3 depicting a different member of the band - John, Paul, George or Ringo. No makers marks. Unusual and rare pieces of Beatles memorabilia. E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) - British Quad film poster (Sci-Fi directed by Steven Spielberg). Classic artwork to front, printed by W. 4 E. Berry Ltd. Folded. Measures approx; 30x40". Rare poster from this Spielberg classic. Along with - a CIC Video release poster, folded with some crumpling. 23x ...[more] Quadrophenia (1979) -A beautiful 16x12" Quadrophenia photographic montage photo, signed by many of the original cast. -

Full Listing of Sunday Night Shows from 1955 to 1974

VAL PARNELL PRESENTS SUNDAY NIGHT AT THE LONDON PALLADIUM 1 25-09-55 Tommy Trinder Gracie Fields, Gus Mitchell, The George Carden Dancers 2 2-10-55 Johnnie Ray, Richard Hearne, Alma Cogan no TVT in Westminster 3 9-10-55 - Norman Wisdom, Jerry Desmonde 4 16-10-55 Tommy Trinder Julie Andrews, Tommy Cooper, The Deep River Boys, The Amandis 5 23-10-55 Tommy Trinder Lena Horne, The Crew Cuts 6 30-10-55 Tommy Trinder Johnny Ray, The Beverley Sisters, Darvis and Julia 7 6-11-55 Tommy Trinder Ruby Murray, Jimmy Jewel and Ben Wariss, Terry-Thomas, Alma Cogan, Leslie Mitchell 8 13-11-55 - The Daily Mirror Disc Festival: Max Bygraves, Eddie Calvert, Alma Cogan, Ted Heath and his Music, Ruby Murray, Joan Regan, The Stargazers, Dickie Valentine, David Whitfield 80 minutes 9 20-11-55 Tommy Trinder Moiseyev Dance Company, Jerry Colonna, Hylda Baker, Channing Pollock 10 27-11-55 Tommy Trinder no guest cast credit 11 4-12-55 Tommy Trinder Dickie Valentine, Patachou 12 11-12-55 Tommy Trinder Bob Hope 13 18-12-55 - Cinderella: Max Bygraves, Richard Hearne, Adele Dixon, Barlett and Ross, Barbara Leigh, Zoe Gail 25-12-55 no programme 14 1-01-56 - Mother Goose: Max Bygraves, Richard Hearne, Hy Hazell, Harry Cranley 15 8-01-56 Tommy Trinder Markova 16 15-01-56 Tommy Trinder no guest cast credit 17 22-01-56 Tommy Trinder Harry Secombe 18 29-01-56 Tommy Trinder Norman Wisdom, Jerry Desmonde, Bob Bromley, The Arnaut Brothers 19 5-02-56 Tommy Trinder Joan Regan, Derek Joy, Morecambe and Wise, The Ganjou Brothers and Juanita, The Mathurins 20 12-02-56 ? no TVT in -

Beatles Tagebuch PT.1 (1964-1) HHB1 BEATLES-1964-01 Beatles Tagebuch PT.1 (1964-1) HHB1 BEATLES-1964-01

Beatles Tagebuch PT.1 (1964-1) HHB1_BEATLES-1964-01 Beatles Tagebuch PT.1 (1964-1) HHB1_BEATLES-1964-01 Nr Titel Label MasterNr. Jahr Nr Titel Jahr CW RB USA GB BRD 03 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND (BEATLES) CAPITOL 5112 1964 03 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND (BEATLES) 1964- - 1 1 1 05 I'LL LET YOU HOLD MY HAND (BOOTLES) GNP 311 1964 05 I'LL LET YOU HOLD MY HAND (BOOTLES) 1964- - - - - C 07 YES YOU CAN HOLD MY HAND (TEEN BUGS) BLUE RIVER 208 1964 07 YES YOU CAN HOLD MY HAND (TEEN BUGS) 1964- - - - - D 09 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAIR (N) (BAGELS) WB 5489 1964 09 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAIR (N) (BAGELS) 1964- - - - - 11 I WANT TO BITE YOUR HAND (N) (GENE MOSS) RCA 47-8438 1964 11 I WANT TO BITE YOUR HAND (N) (GENE MOSS) 1964- - - - - - 13 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND (HOMER & JETHRO) RCA 47-8345 1964 13 I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND (HOMER & JETHRO) 1964- - - - - L 15 KOMM GIB MIR DEINE HAND (I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND) ODEON 22671 1964 15 KOMM GIB MIR DEINE HAND (I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND)* (F) (B 1964- - - - 5 a 17 SEI MIR TREU WIE GOLD (TELL ME WHY)* (F) (DIDI & DIE AB TELEFUNKEN LP 14340 1964 17 SEI MIR TREU WIE GOLD (TELL ME WHY)* (F) (DIDI & DIE ABC BOY 1964- - - - - y 19 TOI L'AMI (ALL MY LOVING)* (F) (RICHARD ANTHONY) COLUMBIA (FRA) EP 2168 1964 19 TOI L'AMI (ALL MY LOVING)* (F) (RICHARD ANTHONY) 1964- - - - - o 21 LITTLE CHILDREN (BILLY J. -

Liverpool Relaunched

34 PART ONE THIS IS MARKETING Liverpool relaunched A golden opportunity to put things right came in Read the questions, then the 2008 when Liverpool became the European Capital of case material, and then answer Culture. Over £2 billion was invested in the city to fund the questions. such ambitious plans as reinventing rundown Para- dise Street as a suitable venue for a variety of enter- tainments, including street theatre and music. The Questions rejuvenation of Liverpool was one of Europe’s biggest 1. What problems did Liverpool face in attracting regeneration projects. The impressive waterfront and tourists? (Use the information in the case study, the city’s fabulous architecture were cleaned up and but you may also want to look up Liverpool, and shown off. New facilities were provided. New hotels rival cities, on the Internet.) were built. This was Liverpool’s chance to show the 2. How could good marketing help to overcome world what a great place it really was. these problems? Liverpool has always had a lot to boast about. As 3. Write a short piece (approx. 200 words) on Liv- well as writers such as Beryl Bainbridge, Willy Rus- erpool for inclusion in a tourist guide. You should sell, Alan Bleasdale, Catherine Cookson and Roger identify different aspects of the city that will appeal McGough, Liverpool has produced many pop-cultural to different types of visitor. icons. More artists with number-one hits were born in 4. How could relationship marketing help Liverpool Liverpool than in any other British city. Its most famous to attract more visitors? sons are, of course, The Beatles. -

Representations of Men and Masculinity May Influence How Men Behave and Feel About Themselves and How This Process Contributes to Social Change for Men

University of Huddersfield Repository King, Martin S "Running like big daft girls." A multi-method study of representations of and reflections on men and masculinities through "The Beatles" Original Citation King, Martin S (2009) "Running like big daft girls." A multi-method study of representations of and reflections on men and masculinities through "The Beatles". Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/9054/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ “RUNNING LIKE BIG DAFT GIRLS.” A MULTI-METHOD STUDY OF REPRESENTATIONS OF AND REFLECTIONS ON MEN AND MASCULINITIES THROUGH “THE BEATLES.” MARTIN KING A Thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Drawing Comic Traditions’ British Television Animation from 1997 to 2010

‘Drawing Comic Traditions’ British Television Animation from 1997 to 2010 Van Norris The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. School of Creative Arts, Film and Media – University of Portsmouth May 2012 1 Contents Front page............................................................................................................1 Contents...............................................................................................................2 Declaration...........................................................................................................7 Abstract................................................................................................................8 Acknowledgements...........................................................................................10 Dissemination....................................................................................................11 Introduction, Rationale, Methodology and Literature Review....................15 Rationale: Animating the industrial and cultural landscape.....17 A marker of the times....................................................................24 Animating Britain..........................................................................29 An alternative to the alternative...................................................34 Methodology...................................................................................35 Literature Review..........................................................................47 -

Old Mother Riley

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 JAN/FEB 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Happy New Year to all our patrons, here’s to 2021! Welcome to the first newsletter of the new year and a big hello to all the new supporters who have joined us over the last few months. We are so grateful to those who sent us Christmas cards, they were greatly appreciated and such lovely words! Did anyone spot the recent news about efforts to save the ruin of The National Picture House cinema in Hull, destroyed by German bombs during the Blitz? All 150 people inside watching The Great Dictator survived. Plans are under way to make the ruin safe for children to visit. This month we bring you a very special DVD release. For the first time ever, the entire series of STAGECOACH WEST is available as a box set with optional subtitles. That’s all 38 episodes, in an 8-DVD Box Set. It’s such a good series, starring Wayne Rogers, Richard Eyer and Robert Bray, with guest stars including James Coburn, DeForest Kelley, Robert Vaughn, Hazel Court, Beverly Garland and James Drury. Good news for Old Mother Riley fans! On pages 22-23 there’s news of seven ‘lost’ films to be shown on Talking Pictures TV, the first on Friday 22nd January at 7:50am, after an Old Mother Riley documentary. A little-known fact about Noël Coward is his involvement with the Actors Orphanage, which he championed and raised money for, bringing joy to the lives of many children. -

Raymond Campbell

Raymond Campbell School of Arts and Digital Industries University of East London Title: Comic Cultures: commerce, aesthetics and the politics of stand-up performance in the UK 1979 to 1992 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 2016 Abstract This thesis represents the first Cultural Studies analysis of the 1980s entertainment form commonly known as ‘alternative comedy’, which emerged against the backdrop of social, industrial and political unrest. However, the use of the term ‘alternative comedy’ has obscured a diverse movement that contained many different strands and tendencies, which included punk poets, street performers, chansonniers and improvising double acts. This thesis goes some way to addressing the complex nature of this entertainment space by recognising the subtle but important differences between New Variety and alternative cabaret. Alternative cabaret was both a movement and an entertainment genre, while New Variety grew out of CAST’s theatre work and was constructed in opposition to Tony Allen’s and Alexei Sayle’s Alternative Cabaret performance collective. Taken together, alternative cabaret and New Variety comprise one part of the alternative space that also includes post-punk music, and were the cultural expressions of the 1980s countercultural milieu. Alternative cabaret and New Variety were the products of cultural change. Each genre has its roots in the countercultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s and it was the knowledge that agents had acquired through participation in these movements that helped to shape their political-aesthetic dispositions or their weltanschauunng. As well as political activism, rock music influenced performers and promoters and contributed much to their art. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 JAN/FEB 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 JAN/FEB 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters, Wishing you all a very Happy New Year! May 2020 be filled with health and happiness. Our first release for 2020 is a brilliant new box set War In Film Volume 1; three discs full of war related films, all restored, plus our exclusive documentary Lest We Forget – all for just £20 with free UK postage. Optional subtitles are available to select on the discs. The set of films includes:Who Goes Next, Subway in the Sky, Desert Mice, The Treasure of San Teresa, During One Night, The Hand, Beyond the Curtain, Mr Kingstreet’s War and shows war from all aspects, not just the gritty and gruesome, but also the human story, humour, sadness, joy and triumph, at home and at the front. Our first event in 2020, The Renown Festival of Film, is just a few weeks away and we are delighted that it is completely sold out – there will be no tickets on the door. We have a wonderful day lined up, which will be revealed in our next newsletter. We have already booked The Stockport Plaza for 2020, Sunday 4th October – do put the date in your diaries. This year tickets for this event will be with numbered seating. We are also looking at a London event and a coastal weekend away in the summer, more details to follow. I spent a great afternoon filming with Sid James’ daughter, the lovely Reina James last year which led me to read one of her books. -

N Ew Sletter

Newsletter No. HISTORY SOCIETY 33 SPRING 2012 Titanic remembered Main image: Builder’s model of Titanic.Top inset: The Museum’s Dawn Littler holds the only known surviving Titanic first class ticket. Titanic and Liverpool: the untold story is the title crew and passengers), Two hours 40 minutes (the ship’s final of a superb new exhibition now showing at the Merseyside hours), Aftermath (media frenzy and official enquiries) and Maritime Museum to mark the 100th anniversary of the sinking Living On (Epilogue of life after Titanic, how survivors coped, of the Liverpool-registered, ‘unsinkable’ Titanic on the 15th April films, myths, conspiracy theories and salvage operations). 1912 with the loss of 1,517 lives. The exhibition’s main strength is its success in telling the The whole world knows the tragic story of Titanic, the largest personal stories of those who were involved, from the hapless and most luxurious liner on earth and pride of the Liverpool- J. Bruce Ismay, Chairman of the White Star Line, to Liverpool- based White Star Line. What is perhaps less well known is just born William McMurray, a first-class bedroom steward. how numerous were Liverpool’s links with the ship. This Complementing this exhibition is the Museum’s other Titanic- exhibition aims to set the record straight. related display: Titanic, Lusitania and the Forgotten Empress Six specially defined areas of the exhibition tell a different story: which features the unique full builder’s model of Titanic. Home Port (Liverpool, of course), Olympic Class (the building “Titanic and Liverpool: the untold story” runs until April 2013. -

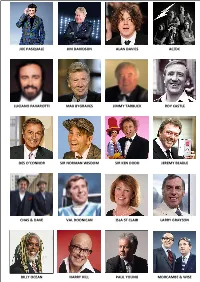

Joe Pasquale Jim Davidson Max Bygraves Jimmy Tarbuck

JOE PASQUALE JIM DAVIDSON ALAN DAVIES AC/DC LUCIANO PAVAROTTI MAX BYGRAVES JIMMY TARBUCK ROY CASTLE DES O’CONNOR SIR NORMAN WISDOM SIR KEN DODD JEREMY BEADLE CHAS & DAVE VAL DOONICAN ISLA ST CLAIR LARRY GRAYSON BILLY OCEAN HARRY HILL PAUL YOUNG MORCAMBE & WISE THE TREORCHY CHOIR ALEX HIGGINS GERRY MARSDEN DAVE DEE SUZI QUATRO RAY ALAN NORMAN COLLIER FRANK CARSON THE COMMITMENTS BOBBY KNUTT CILLA BLACK BARBARA WINDSOR DAVE BERRY FREDDIE STARR THE SUPREMES JIMMY WHITE RONNIE O’SULLIVAN STAN BOARDMAN FRANKIE VAUGHAN JIMMY GREAVES KATHY KIRBY ALVIN STARDUST THE TROGGS JASPER CARROTT BEV BEVAN THE HOLLIES MIKE YARWOOD MOTÖRHEAD SIR BOB GELDOF THE DRIFTERS ROY ‘CHUBBY’ BROWN RHOD GILBERT VICTORIA WOOD JIMMY CRICKET BERT WEEDON JOE LOSS CHUCKLE BROTHERS SOOTY DICKIE HENDERSON BOB MONKHOUSE RICK WAKEMAN MARTY WILDE THE STYLISTICS JIMMY CARR PADDY McGUINNESS MATTHEW FORD DAVE ALLEN STEVE DAVIS MARTI CAINE NEW AMEN CORNER STEVE BEATON JAKE THACKRAY DICK EMERY ED BYRNE DENNIS LOTIS FRED DIBNAH RUSSELL WATSON BILL HALEY THE PLATTERS WHITESNAKE HUMPHREY LYTTLETON BILL MAYNARD DAVID NIXON HENRY BLOFELD SHAKIN’ STEVENS SUSIE BLAKE KATE ROBBINS EDWIN STARR JET HARRIS ARTHUR BOSTROM DR FEELGOOD MICK MILLER GIANT HAYSTACKS GEORGE HAMILTON IV DEBBIE McGEE PAUL DANIELS MARTHA REEVES WENDY PETERS SHOWADDYWADDY DAVID DICKINSON ASWAD RAY QUINN THE BEVERLEY SISTERS STU FRANCIS CRISSY ROCK SIMON RATTLE TED HEATH THE ROCKIN’ BERRIES DEL SHANNON HEAVY METAL KIDS CHRIS RAMSEY BRIAN BLESSED DON MACLEAN FOSTER & ALLEN JUDAS PRIEST ERIC DELANEY PAM AYRES DAVID SHEPHERD