Drawing Comic Traditions’ British Television Animation from 1997 to 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

Barbie Bake-Off and Risk Or Role the Apprentice Model? Documentary Pokémon Go Shorts

FEBRUARY 2017 ISSUE 59 POST-TRUTH RESEARCHING THE PAST BARBIE BAKE-OFF AND RISK OR ROLE THE APPRENTICE MODEL? DOCUMENTARY POKÉMON GO SHORTS MM59_cover_4_feb.indd 1 06/02/2017 14:00 Contents 04 Making the Most of MediaMag MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media 06 What’s the Truth in a Centre, a non-profit making Post-fact World? organisation. The Centre Nick Lacey explores the role publishes a wide range of of misinformation in recent classroom materials and electoral campaigns, and runs courses for teachers. asks who is responsible for If you’re studying English 06 gate-keeping online news. at A Level, look out for emagazine, also published 10 NW and the Image by the Centre. System at Work in the World Andrew McCallum explores the complexities of image and identify in the BBC television 30 16 adaptation of Zadie Smith’s acclaimed novel, NW. 16 Operation Julie: Researching the Past Screenwriter Mike Hobbs describes the challenges of researching a script for a sensational crime story forty years after the event. 20 20 Bun Fight: How The BBC The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace Lost Bake Off to Channel 4 London N1 2UN and Why it Matters Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Jonathan Nunns examines Fax: 020 7354 0133 why the acquisition of Bake Email for subscription enquiries: Off may be less than a bun [email protected] in the oven for Channel 4. 25 Mirror, Mirror, on the Editor: Jenny Grahame Wall… Mark Ramey introduces Copy-editing: some of the big questions we Andrew McCallum should be asking about the Subscriptions manager: nature of documentary film Bev St Hill 10 and its relationship to reality. -

06 6-23-09 TV Guide.Indd 1 6/23/09 8:00:20 AM

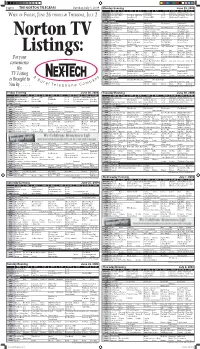

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 3, 2009 Monday Evening June 29, 2009 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette Newlyweds Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JUNE 26 THROUGH THURSDAY , JULY 2 KBSH/CBS How I Met Rules Two Men Big Bang CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Law & Order Law Order: CI Dateline NBC Local Wimbledon Tonight Show FOX House Lie to Me Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Obsessed The Cleaner Intervention AMC The Whole Nine Yards Starsky & Hutch The Whole Nine Yards ANIM Most Outrageous Dogs 101 Animal Cops Most Outrageous Dogs 101 CNN Campbell Brown Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Swamp Loggers Swamp Loggers Dirty Jobs Swamp Loggers DISN Holes Wizards Montana The Suite So Raven Life With Cory E! Fatal Beauty Wildest The Dish Chelsea E! News Chelsea SNL Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 Series of Poker Series of Poker Series of Poker Series of Poker NASCAR Now FAM Secret-Teen Make It or Break It Secret-Teen The 700 Club Secret-Teen FX Ice Age Ice Age: Melt Just Married HGTV Property Property House My First House For Rent HGTV Showdown Property Property HIST Secrets-Fathers Beltway Unbuckled Secrets-Fathers LIFE Reba Reba Army Wives Desperate Housewives Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV True Life Run Run Run Run Run Run Going Out Library Listings: NICK School SpongeBob Home Imp. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Le Scatole Magiche È Un film Evento Per Famiglie Dei Creatori Di Coraline E La Porta Magica E Paranorman, Entrambi Candidati All'oscar Per Il Miglior Film D'animazione

Pressbook italiano Presentano Un film diretto da ANTHONY STACCHI e GRAHAM ANNABLE Tratto dal romanzo best seller di ALAN SNOW “Arrivano I Mostri” (Here be Monsters!) Con le voci originali di: Ben Kingsley, Isaac Hempstead Wright, Elle Fanning, Dee Bradley Baker, Steve Blum, Toni Collette, Jared Harris, Nick Frost, Richard Ayoade, Tracy Morgan, e Simon Pegg Prodotto da DAVID BLEIMAN ICHIOKA, PGA TRAVIS KNIGHT, PGA Scritto da IRENA BRIGNULL ADAM PAVA Direttore della Fotografia JOHN ASHLEE PRAT Uscita Italiana: 2 Ottobre 2014 Durata del Film: 97 minuti Il materiale fotografico è disponibile sul sito www.upimedia.com Ufficio Stampa Universal Pictures International Italy: Cristina Casati – [email protected] Marina Caprioli – [email protected] Matilde Marinai – [email protected] 1 Pressbook italiano Indice I. Sinossi pag 3 II. La Nascita dello Stop-Motion pag 5 III. Fuori dai Cartoni pag 7 IV. Dar Voce Anche Alle Scatole pag 11 V. I Boxtrolls Si Muovono pag 22 VI. I LAIKAni pag 42 VII. Ritocchi Finali pag 49 VIII. Tutti i Numeri di Boxtrolls pag 52 IX. Il Cast Artistico page 54 X. Il Cast Tecnico page 63 2 Pressbook italiano Sinossi Boxtrolls- Le Scatole Magiche è un film evento per famiglie dei creatori di Coraline e la Porta Magica e ParaNorman, entrambi candidati all'Oscar per il Miglior Film d'Animazione. Si tratta della terza produzione cinematografica dello studio d’animazione con sede in Oregon, LAIKA. Girato in loco presso gli studi LAIKA, in 3D e con metodi avanzati manuali e tecnologici, Boxtrolls- Le Scatole Magiche utilizza disegni manuali, formato grafico ibrido d’animazione in CG e tecnica dello stop-motion, per rappresentare la storia del best-seller fantasy d’ avventura di Alan Snow “Arrivano I Mostri!”. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Stash03 18494 Maya6 Stash Ad 5/5/04 10:41 AM Page 1 Yes, It’S True

DVD MAGAZINE Outstanding animation, VFX and motion graphics for design and advertising stash03 18494_Maya6_Stash Ad 5/5/04 10:41 AM Page 1 Yes, it’s true. Stash is off to a rip-snorting start. Our third issue, code named Stash 03, will land on the desks of visually acute stashDVD MAGAZINE and well-adjusted professionals in 30 countries on six contients - thank you Kuwait, Cypress and Nigeria. Those desks belong STASH MEDIA INC. to ad agencies, broadcasters, animation studios, post houses, Editor: STEPHEN PRICE producers, directors, creative directors, art directors, copywriters, Publisher: GREG ROBINS Associate editor: HEATHER GRIEVE editors, animators, designers, students and a dental receptionist DVD production: METROPOLIS DVD, in Dallas taking Maya and After Effects classes at night - thank New York you Maureen. This issue will also be available at discerning yet Animation: KYLE SIM, TOPIX, Toronto Toolkit: 3DS Max, Inferno friendly online retailers and terrestrial bookstores in New York, Music: TREVOR MORRIS, Toronto, Los Angeles, Vancouver and Singapore with London to Media Ventures, Santa Monica follow soon. Thanks: CHEYENNE, MAYA, NICOLE, JASON, TYLER, RADIOIO.COM Cover Image: Honda “Grrr” courtesy NEXUS PRODUCTIONS, London But wait, there’s more - we just renovated the website, rented Stash toolkit: Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, Transmit, Powerbook G4s, sunny new digs at Broadway and 12th from real nice people and Helvetica Neue, DIN Mittellschrift retained the multi-talented Heather G to keep us sane. Instructions: Fluff with a fork. SUBSCRIBE at www.stashmedia.tv Looks like this would be the time to get those submissions in Legal things: Stash Magazine and Stash DVD are published 12 times per year by Stash ‘cause I’m in a really good mood.