Current Perspectives in Sudanese and Nubian Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Egypt During the Coptic Period

Paper Abstracts of the First International Coptic Studies Conference Life in Egypt during the Coptic Period From Coptic to Arabic in the Christian Literature of Egypt Adel Y. Sidarus Evora, Portugal After having made the point on multilingualism in Egypt under Graeco- Roman domination (2008/2009), I intend to investigate the situation in the early centuries of Arab Islamic rule (7th–10th centuries). I will look for the shift from Coptic to Arabic in the Christian literature: the last period of literary expression in Coptic, with the decline of Sahidic and the rise of Bohairic, and the beginning of the new Arabic stage. I will try in particular to discover the reasons for the tardiness in the emergence of Copto-Arabic literature in comparison with Graeco-Arabic or Syro-Arabic, not without examining the literary output of the Melkite community of Egypt and of the other minority groups represented by the Jews, but also of Islamic literature in general. Was There a Coptic Community in Greece? Reading in the Text of Evliya Çelebi Ahmed M. M. Amin Fayoum University Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) is a well-known Turkish traveler who was visiting Greece during 1667–71 and described the Greek cities in his interesting work "Seyahatname". Çelebi mentioned that there was an Egyptian community called "Pharaohs" in the city of Komotini; located in northern Greece, and they spoke their own language; the "Coptic dialect". Çelebi wrote around five pages about this subject and mentioned many incredible stories relating the Prophets Moses, Youssef and Mohamed with Egypt, and other stories about Coptic traditions, ethics and language as well. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Survey and Salvage Epigraphy of Rock-Cut Graffiti and Inscriptions in the Area of Aswan Report on the Season in Autumn 2012 and Spring 2013

Survey and Salvage Epigraphy of Rock-Cut Graffiti and Inscriptions in the Area of Aswan Report on the Season in Autumn 2012 and Spring 2013 by Linda Borrmann (German Archaeological Institute Cairo) 1) Introduction 2) The site of the Royal Stelae south of Aswan a. Setting b. Stelae c. Further inscriptions d. Preliminary results 3) Rock art in Wadi Berber on the West Bank of Aswan a. Setting b. Rock art c. Landscape and spatial recording 1) Introduction From October 23, 2012 until December 05, 2012 and from March 03, 2013 until March 07, 2013 work on surveying and salvage epigraphy on rock inscriptions and rock art in the Aswan area was continued in the framework of the joint project between the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and the Ministry of State for Antiquities (MSA).1 During this field season work on a group of New Kingdom royal stelae situated south of the town of Aswan (behind the workshop "Turquoise Joaillerie") and at a rock art site in Wadi Berber on the West Bank of Aswan was completed. 1 Members of the team were: Dr. Fathy Abu Zeid (head of the mission, MSA), Dr. Abd el Hakim Karrar (head of the mission, MSA), Prof. Dr. Stephan Seidlmayer (head of the mission, DAI Cairo), Linda Borrmann M.A. (field director, DAI Cairo), Adel Kelany (field director, MSA), Rebecca Döhl M.A. (sub-project “Rock Art in Wadi Berber”), Shazli Ali Abd el Azim, Alexander Juraschka, Anita Kriener M.A., Mahmoud Mamdouh Mokhtar, Ahmed Mohamed Hassan Mohamed, Heba Saad Harby, Elisabeth Wegner (members of the collaborative team), Mohamed Abdu Ali, Salah el Deen Ismael Abd el Raof, Yosra Khalf Allah el Zohry, Ahmed Mohamed Ahmed (trainees of the MSA). -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

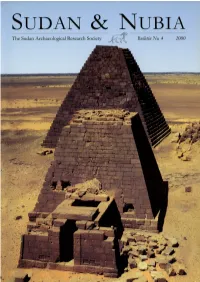

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: an Archaeological Note

Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Volume 3 Know-Hows and Techniques in Ancient Sudan Article 3 2016 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sebastien Maillot [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns Recommended Citation Maillot, Sebastien (2016) "Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note," Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns/vol3/iss1/3 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 41 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sébastien Maillot* The Kushite temples of Amun at Dukki Gel1 and Dangeil2 (fig. 1) fea- ture in their precincts large heaps of ash mixed with ceramic coni- cal moulds (or “bread moulds”), which are dumps associated with the production of food offerings for the cult. Excavation of the areas dedicated to these activities resumed in 2013 at both sites, uncover- ing numerous firing and storage features. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty. -

Mud-Brick Architecture

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mud-Brick Architecture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4983w678 Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Emery, Virginia L. Publication Date 2011-02-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Emery, 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. UEE. Full Citation: Emery, Virginia L., 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb 1146 Version 1, February 2011 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery Ziegelarchitektur L’architecture en brique crue Mud-brick architecture, though it has received less academic attention than stone architecture, was in fact the more common of the two in ancient Egypt; unfired brick, made from mud, river, or desert clay, was used as the primary building material for houses throughout Egyptian history and was employed alongside stone in tombs and temples of all eras and regions. Construction of walls and vaults in mud-brick was economical and relatively technically uncomplicated, and mud-brick architecture provided a more comfortable and more adaptable living and working environment when compared to stone buildings. على الرغم أن العمارة بالطوب اللبن تلقت إھتماما أقل من العمارة الحجرية من قِبَل المتخصصين، فقد كانت في الواقع تلك العمارة ھي اﻷكثر شيوعا في مصر القديمة، وكان الطوب اللبن (أوالنيء) المصنوع من الطمي أو الطين الصحراوي مستخدما كمادة بناء بدائية للمنازل على مدار التاريخ المصري واستخدمت إلى جانب الحجارة في المقابر والمعابد في جميع المناطق وخﻻل جميع الفترات. -

The Origins and Afterlives of Kush

THE ORIGINS AND AFTERLIVES OF KUSH ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED FOR THE CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA: JULY 25TH - 27TH, 2019 Introduction ....................................................................................................3 Mohamed Ali - Meroitic Political Economy from a Regional Perspective ........................4 Brenda J. Baker - Kush Above the Fourth Cataract: Insights from the Bioarcheology of Nubia expedition ......................................................................................................4 Stanley M. Burnstein - The Phenon Letter and the Function of Greek in Post-Meroitic Nubia ......................................................................................................................5 Michele R. Buzon - Countering the Racist Scholarship of Morphological Research in Nubia ......................................................................................................................6 Susan K. Doll - The Unusual Tomb of Irtieru at Nuri .....................................................6 Denise Doxey and Susanne Gänsicke - The Auloi from Meroe: Reconstructing the Instruments from Queen Amanishakheto’s Pyramid ......................................................7 Faïza Drici - Between Triumph and Defeat: The Legacy of THE Egyptian New Kingdom in Meroitic Martial Imagery ..........................................................................................7 Salim Faraji - William Leo Hansberry, Pioneer of Africana Nubiology: Toward a Transdisciplinary