The Rhetoric of Noh: Border Crossings in Karukaya and Tadatsu No Saemon and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noh and Kyogen

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater Noh performance Scene of Hirota Yukitoshi in the noh drama Kagetsu (Flowers and Moon) performed at the 49th Commemorative Noh event. (Photo courtesy of The Nohgaku Performers’ Association) Noh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions forms of classical theater, the other two being were touring and performing at temples, kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its shrines, and festivals, often with the broadest sense includes the comic theater patronage of the nobility. The performing kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical genre called sarugaku was one of these form in the 14th century, making it the oldest traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors extant professional theater in the world. Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami Although noh and kyogen developed together (1363–1443) transformed sarugaku into noh and are inseparable, they are in many ways in basically the same form as it is still exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a performed today. Kan’ami introduced the symbolic theater with primary importance music and dance elements of the popular attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied entertainment kuse-mai into sarugaku, and he aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other attracted the attention and patronage of hand, primary importance is attached to Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu making people laugh. (1358–1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance History of the Noh to further refine the noh aesthetic principles of Theater monomane (the imitation of things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a the suggestion of mystery and depth. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

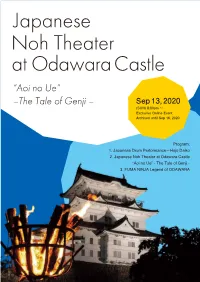

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Anxiety of Erotic Longing and Murasaki Shikibu's Aesthetic Vision

Bulletin of the International Research JAR\NREVIEW I Center for Japanese Studies Dirrctor-General -- KAWAI, Hayao InternationalResearch CenterforJapanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan Editor-in-Chief SUZUKI, Sadami InternationalResearch CenterforJapanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan Associate Editors ISHIT, Shiro International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto. Japan KURIYAMA, Shigehisa International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Kyoto. Japan KUROSU, Satomi International Research CenterforJapanese Studies, &lo, Japan Editorial Advisory Board Bjorn E. BERGLUND Josef KREINER University ofLund, Lund, Sweden Deutsches Institiit.fiirJapansiudien,Tokyo, Japan Augustin BERQUE Olof G. LIDIN ~coledes Homes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, France University ofCopenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark Selpk ESENBEL Mikotaj MELANOWICZ Bosphorus University, Istanbul, Turkey Warsaw L'niversi[\: Warsaw. Poland IRIYE, Akira Earl MINER Harvard University, Cambridge, U. S. A. Princeton Universic, Princeton, U. S. A. Marius B. JANSEN Satya Bhushan VERMA Princeton University, Princeton, U. S. A. Jawaharlal Nehnt University. New Delhi, India KIM, Un Jon Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea JAPAN REVIEW-Bulletin of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Aims and Scope of the Bulletin Japan Review aims to publish original articles, review articles, research notes and materials, technical reports and book reviews in the field of Japanese culture and civilization. Occasionally English translations of outstanding articles may also be considered. It is hoped that the bulletin will contribute to the development of international and interdisciplinary Japanese studies. Submission of Manuscripts Manuscripts should be sent to the Editors of Japan Review. International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 3-2 Oeyama-cho, Goryo, Nishiio-ku, Kyoto 610-1 192, Japan Editorial Policy Japan Review is open to members of the research staff, joint researchers, administrative advisors and participants in the activities of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. -

Nohand Kyogen

For more detailed information on Japanese government policy and other such matters, see the following home pages. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website http://www.mofa.go.jp/ Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater oh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four N forms of classical theater, the other two being kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its broadest sense includes the comic theater kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical form in the 14th century, making it the oldest extant professional theater in the world. Although noh and kyogen developed together and are inseparable, they are in many ways exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a symbolic theater with primary importance attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other hand, primary importance is attached to making people laugh. History of the Noh Theater Noh performance chance to further refine the noh aesthetic Scene from a Kanze In the early 14th century, acting troupes principles of monomane (the imitation of school performance of the in a variety of centuries-old theatrical play Aoi no ue (Lady Aoi). things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic © National Noh Theater traditions were touring and performing ideal emphasizing the suggestion of mystery at temples, shrines, and festivals, often and depth. In addition to writing some of with the patronage of the nobility. The the best-known plays in the noh repertoire, performing genre called sarugaku was one Zeami wrote a series of essays which of these traditions. The brilliant playwrights defined the standards for noh performance and actors Kan’ami (1333– 1384) and his son in the centuries that followed. -

The Tale of Genji” and Its Selected Adaptations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Anna Kuchta Instytut Filozo!i, Uniwersytet Jagielloński Joanna Malita Instytut Religioznawstwa, Uniwersytet Jagielloński Spirit possession and emotional suffering in „The Tale of Genji” and its selected adaptations. A study of love triangle between Prince Genji, Lady Aoi and Lady Rokujō Considered a fundamental work of Japanese literature – even the whole Japanese culture – !e Tale of Genji, written a thousand years ago by lady Murasaki Shikibu (a lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court of the empress Shōshi1 in Heian Japan2), continues to awe the readers and inspire the artists up to the 21st century. %e amount of adaptations of the story, including more traditional arts (like Nō theatre) and modern versions (here !lms, manga and anime can be mentioned) only proves the timeless value and importance of the tale. %e academics have always regarded !e Tale of Genji as a very abundant source, too, as numerous analyses and studies have been produced hitherto. %is article intends to add to the perception of spiri- tual possession in the novel itself, as well as in selected adaptations. From poems to scents, from courtly romance to political intrigues: Shikibu covers the life of aristocrats so thoroughly that it became one of the main sour- ces of knowledge about Heian music3. Murasaki’s novel depicts the perfect male, 1 For the transcript of the Japanese words and names, the Hepburn romanisation system is used. %e Japanese names are given in the Japanese order (with family name !rst and personal name second). -

Noda Hideki's English Plays

Noda Hideki’s English plays Wolfgang Zoubek 本文よりコピーして貼り付け Yの値は105です! 文字大きさそのままです 富山大学人文学部紀要第58号抜刷 2013年2月 富山大学人文学部紀要 Noda Hideki’s English plays Noda Hideki’s English plays Wolfgang Zoubek Introduction Noda Hideki1) (born 1955) is a well-known Japanese theater practitioner who has been famous since the late seventies with his troupe Yume no Yûminsha [The Dream Wanderers]. He has produced many fictional plays in a modern fairytale style. In the 1980s, he became one of the leading representatives of Japanese contemporary theater. In the 1990s, he began incorporating more social commentary in his themes. Nowadays he remains as successful as ever. This paper will focus on three of Noda’s plays, all of which were performed abroad in English: Red Demon, The Bee and The Diver. After a review of his early career and his rise to success, his efforts and struggles in bringing these plays to foreign audiences will be examined in detail, covering topics such as historical influences, comparisons with Japanese versions and critical reactions. The primary question under investigation is this: To what degree has Noda been successful at bringing his vision of Japanese contemporary theater to non-Japanese audiences? For readers not familiar with Noda’s body of work, brief plot summaries of each play as well as explanation of background source material will be provided. Early career Noda Hideki’s theatrical career began in 1976 when the Dream Wanderers attracted attention during a competition for young, unknown performers in Tokyo 1)Noda is the family name, Hideki the given name. In Japan usually the family name is written first. -

Noh and Kyogen

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater Noh performance Scene of Hirota Yukitoshi in the noh drama Kagetsu (Flowers and Moon) performed at the 49th Commemorative Noh event. (Photo courtesy of The Nohgaku Performers’ Association) Noh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions forms of classical theater, the other two being were touring and performing at temples, kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its shrines, and festivals, often with the broadest sense includes the comic theater patronage of the nobility. The performing kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical genre called sarugaku was one of these form in the 14th century, making it the oldest traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors extant professional theater in the world. Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami Although noh and kyogen developed together (1363–1443) transformed sarugaku into noh and are inseparable, they are in many ways in basically the same form as it is still exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a performed today. Kan’ami introduced the symbolic theater with primary importance music and dance elements of the popular attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied entertainment kuse-mai into sarugaku, and he aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other attracted the attention and patronage of hand, primary importance is attached to Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu making people laugh. (1358–1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance History of the Noh to further refine the noh aesthetic principles of Theater monomane (the imitation of things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a the suggestion of mystery and depth. -

Gender and Spiritual Possession in the Tale of Genji

Bellarmine University ScholarWorks@Bellarmine Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Works 4-27-2018 Gender and Spiritual Possession in The Tale of Genji Molly Phelps [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Phelps, Molly, "Gender and Spiritual Possession in The Tale of Genji" (2018). Undergraduate Theses. 28. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/28 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Works at ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Gender and Spiritual Possession in The Tale of Genji Molly Phelps Spring 2018 Directed by Dr. Jon Blandford Phelps 1 Dedication This thesis could only exist through the endless support I received from others. I would like to thank my mother and my sister for being with me at every step of the way up to now. I would like to thank Mary, Audrie, and Eli for making my time at Bellarmine University truly special. I would like to thank my readers, Dr. Jennifer Barker and Dr. Kendra Sheehan, for providing me much needed insight to both my writing and Japanese history. Finally, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jon Blandford. Your guidance has been one of the most valuable resources that Bellarmine University has offered. Thank you for both your assistance through this process and for your tireless dedication to the Honors Program. -

Tale of the Genji

NORMA FIELD The Splendor of Longing in the Tale of the Genji PRINCETON LEGACY LIBRARY The Splendor of Longing in the Tale of Genji Norma Field The Splendor of Longing in the Tale ofGenji PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1987 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom Princeton University Press, Guildford, Surrey All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging m Publication Data will be found on the last printed page of this book ISBN 0-691-06691-4 (cloth) 01436-1 (pbk) Publication of this book has been aided by grants from the Suntory Foundation and the Japan Foundation This book has been composed in Linotron Electro Clothbound editions of Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and binding materials are chosen for strength and durability Paperbacks, although satisfactory for personal collections, are not usually suitable for library rebmding Printed in the United States of America by Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey Frontispiece "Yugiri," Genji Monogatari Emaki, early twelfth century Goto Art Museum, Tokyo DESIGNED BY LAURY A EGAN Princeton Legacy Library edition 2019 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-60981-2 Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-691-65616-8 For Rodger Contents Preface ix Principal Characters xiii Introduction 3 Chapter I. Three Heroines and the Making of the Hero 18 Dichotomies and Substitution Fu]itsubo 18 Transgression, Exile, and the Development of Fiction 33 The Roku]o Lady Pride and Possession 45 The Elusive Self in Heian Japan 51 Meeting in Exile 64 At the Capital The Akashi Lady as Urban Aristocrat 74 Chapter 2. -

Reginald Jackson

Theatre Survey 60:3 (September 2019) © American Society for Theatre Research 2019 doi:10.1017/S0040557419000255 Reginald Jackson FRAYED FABRICATIONS:FEMININE MOBILITY,SURROGATE BODIES, AND ROBE USAGE IN NOH DRAMA Nageki wabi sora ni midaruru wagatama wo musubitodome yo shitagahe no tsuma [Bind it down for me! My strewn soul: wailing, wounded, rambles ragged skies. Knot this robe-skirt’s inside hem—slit like a flung-aside wife.] —The Tale of Genji1 How should we understand the role robes play within noh dance-drama’s enact- ments of femininity? In the above poem Genji’s jilted lover, Rokujō, bemoans her inability to keep her vengeful spirit from besieging the Lady Aoi, for whom Genji has spurned her. Within the worldview of Murasaki Shikibu’s early eleventh-century narrative, to bind the hem was to tether the restless spirit to its host’s body, like a tourniquet stanching spectral energies from seeping to infect victims.2 The famous noh play Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi), in which Aoi is played not by an actor but by a short-sleeved robe (kosode), activates the poem’s meta- phor onstage. Moreover, the Japanese poem’s final term, tsuma, signifies both Reginald Jackson is an associate professor of premodern Japanese literature and performance at the University of Michigan. His research interests include premodern Japanese visual culture, noh dance-drama, queer studies, transla- tion, and contemporary choreography. He is the author of Textures of Mourning: Calligraphy, Mortality, and “The Tale of Genji” Scrolls (University of Michigan Press, 2018), and A Proximate Remove: Queering Intimacy and Loss in “The Tale of Genji” (under review).