Pre-Modern Japanese Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Aesthetics and the Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] T

Japanese Aesthetics and The Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Themes and Uses 2. Instructor’s Introduction 3. Student Readings 4. Discussion Questions 5. Sample Writing Assignments 6. Further Reading and Resources 1. Themes and Uses Using an excerpt from the chapter “The Sacred Tree,” this unit offers a guide to a close examination of Japanese aesthetics in The Tale of Genji (ca.1010). This two-session lesson plan can be used in World Literature courses or any course that teaches components of Zen Buddhism or Japanese aesthetics (e.g. Introduction to Buddhism, the History of Buddhism, Philosophy, Japanese History, Asian Literature, or World Religion). Specifically, the lesson plan aims at helping students develop a deeper appreciation for both the novel and important concepts of Japanese aesthetics. Over the centuries since its composition, Genji has been read through the lenses of some of the following terms, which are explored in this unit: • miyabi (“courtly elegance”; refers to the aristocracy’s privileging of a refined aesthetic sensibility and an indirectness of expression) • mono no aware (the “poignant beauty of things;” describes a cultivated sensitivity to the ineluctable transience of the world) • wabi-sabi (wabi can be translated as “rustic beauty” and sabi as “desolate beauty;” the qualities usually associated with wabi and sabi are austerity, imperfection, and a palpable sense of the passage of time. • yûgen (an emotion, a sentiment, or a mood so subtle and profoundly elegant that it is beyond what words can describe) For further explanation of these concepts, see the unit “Buddhism and Japanese Aesthetics” (forthcoming on the ExEAS website.) 2. -

Noh and Kyogen

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater Noh performance Scene of Hirota Yukitoshi in the noh drama Kagetsu (Flowers and Moon) performed at the 49th Commemorative Noh event. (Photo courtesy of The Nohgaku Performers’ Association) Noh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions forms of classical theater, the other two being were touring and performing at temples, kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its shrines, and festivals, often with the broadest sense includes the comic theater patronage of the nobility. The performing kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical genre called sarugaku was one of these form in the 14th century, making it the oldest traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors extant professional theater in the world. Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami Although noh and kyogen developed together (1363–1443) transformed sarugaku into noh and are inseparable, they are in many ways in basically the same form as it is still exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a performed today. Kan’ami introduced the symbolic theater with primary importance music and dance elements of the popular attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied entertainment kuse-mai into sarugaku, and he aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other attracted the attention and patronage of hand, primary importance is attached to Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu making people laugh. (1358–1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance History of the Noh to further refine the noh aesthetic principles of Theater monomane (the imitation of things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a the suggestion of mystery and depth. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bk827db Author Chudnow, Matthew Thomas Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. -

What Genji Paintings Do

Beyond Narrative Illustration: What Genji Paintings Do MELISSA McCORMICK ithin one hundred fifty years of its creation, gold found in the paper decoration of their accompanying cal- The Tale of Genji had been reproduced in a luxurious ligraphic texts (fig. 12). W set of illustrated handscrolls that afforded privileged In this scene from Chapter 38, “Bell Crickets” (Suzumushi II), for readers a synesthetic experience of Murasaki Shikibu’s tale. Those example, vaporous clouds in the upper right corner overlap directly twelfth-century scrolls, now designated National Treasures, with the representation of a building’s veranda. A large autumn survive in fragmented form today and continue to offer some of moon appears in thin outline within this dark haze, its brilliant the most evocative interpretations of the story ever imagined. illumination implied by the silver pigment that covers the ground Although the Genji Scrolls represent a singular moment in the his- below. The cloud patch here functions as a vehicle for presenting tory of depicting the tale, they provide an important starting point the moon, and, as clouds and mist bands will continue to do in for understanding later illustrations. They are relevant to nearly Genji paintings for centuries to come, it suggests a conflation of all later Genji paintings because of their shared pictorial language, time and space within a limited pictorial field. The impossibility of their synergistic relationship between text and image, and the the moon’s position on the veranda untethers the motif from literal collaborative artistic process that brought them into being. Starting representation, allowing it to refer, for example, to a different with these earliest scrolls, this essay serves as an introduction to temporal moment than the one pictured. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Songs of the Righteous Spirit: “Men of High Purpose” and Their Chinese Poetry in Modern Japan MATTHEW FRALEIGH Brandeis University

Songs of the Righteous Spirit: “Men of High Purpose” and Their Chinese Poetry in Modern Japan MATTHEW FRALEIGH Brandeis University he term “men of high purpose” (shishi 志士) is most com- monly associated with a diverse group of men active in a wide rangeT of pro-imperial and nationalist causes in mid-nineteenth- century Japan.1 In a broader sense, the category of shishi embraces not only men of scholarly inclination, such as Fujita Tōko 藤田東湖, Sakuma Shōzan 佐久間象山, and Yoshida Shōin 吉田松陰, but also the less eru dite samurai militants who were involved in political assas sinations, attacks on foreigners, and full-fledged warfare from the 1850s through the 1870s. Before the Meiji Restoration, the targets of shishi activism included rival domains and the Tokugawa shogunate; after 1868, some disaffected shishi identified a new enemy in the early Meiji oligarchy (a group that was itself composed of many former shishi). Although they I have presented portions of my work on this topic at the Annual Meeting of the Associa- tion for Asian Studies, Boston, March 27, 2007, as well as at colloquia at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Brandeis University. On each occasion, I have benefited from the comments and questions of audience members. I would also like to thank in particu- lar the two anonymous reviewers of the manuscript, whose detailed comments have been immensely helpful. 1 I use Thomas Huber’s translation of the term shishi as “men of high purpose”; his article provides an excellent introduction to several major shishi actions in the 1860s. -

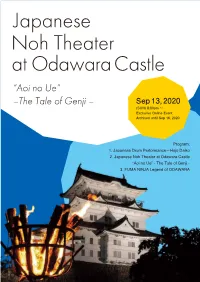

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Anxiety of Erotic Longing and Murasaki Shikibu's Aesthetic Vision

Bulletin of the International Research JAR\NREVIEW I Center for Japanese Studies Dirrctor-General -- KAWAI, Hayao InternationalResearch CenterforJapanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan Editor-in-Chief SUZUKI, Sadami InternationalResearch CenterforJapanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan Associate Editors ISHIT, Shiro International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto. Japan KURIYAMA, Shigehisa International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Kyoto. Japan KUROSU, Satomi International Research CenterforJapanese Studies, &lo, Japan Editorial Advisory Board Bjorn E. BERGLUND Josef KREINER University ofLund, Lund, Sweden Deutsches Institiit.fiirJapansiudien,Tokyo, Japan Augustin BERQUE Olof G. LIDIN ~coledes Homes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, France University ofCopenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark Selpk ESENBEL Mikotaj MELANOWICZ Bosphorus University, Istanbul, Turkey Warsaw L'niversi[\: Warsaw. Poland IRIYE, Akira Earl MINER Harvard University, Cambridge, U. S. A. Princeton Universic, Princeton, U. S. A. Marius B. JANSEN Satya Bhushan VERMA Princeton University, Princeton, U. S. A. Jawaharlal Nehnt University. New Delhi, India KIM, Un Jon Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea JAPAN REVIEW-Bulletin of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Aims and Scope of the Bulletin Japan Review aims to publish original articles, review articles, research notes and materials, technical reports and book reviews in the field of Japanese culture and civilization. Occasionally English translations of outstanding articles may also be considered. It is hoped that the bulletin will contribute to the development of international and interdisciplinary Japanese studies. Submission of Manuscripts Manuscripts should be sent to the Editors of Japan Review. International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 3-2 Oeyama-cho, Goryo, Nishiio-ku, Kyoto 610-1 192, Japan Editorial Policy Japan Review is open to members of the research staff, joint researchers, administrative advisors and participants in the activities of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. -

A COMPARISON of the MURASAKI SHIKIBU DIARY and the LETTER of ABUTSU Carolina Negri

Rivista degli Studi Orientali 2017.qxp_Impaginato 26/02/18 08:37 Pagina 281 REFERENCE MANUALS FOR YOUNG LADIES-IN-WAITING: A COMPARISON OF THE MURASAKI SHIKIBU DIARY AND THE LETTER OF ABUTSU Carolina Negri The nature of the epistolary genre was revealed to me: a form of writing devoted to another person. Novels, poems, and so on, were texts into which others were free to enter, or not. Letters, on the other hand, did not exist without the other person, and their very mission, their signifcance, was the epiphany of the recipient. Amélie Nothomb, Une forme de vie The paper focuses on the comparison between two works written for women’s educa- tion in ancient Japan: The Murasaki Shikibu nikki (the Murasaki Shikibu Diary, early 11th century) and the Abutsu no fumi (the Letter of Abutsu, 1263). Like many literary docu- ments produced in the Heian (794-1185) and in the Kamakura (1185-1333) periods they describe the hard life in the service of aristocratic fgures and the difculty of managing relationships with other people. Both are intended to show women what positive ef- fects might arise from sharing certain examples of good conduct and at the same time, the inevitable negative consequences on those who rejected them. Keywords: Murasaki Shikibu nikki; Abutsu no fumi; ladies-in.waiting; letters; women’s education 1. “The epistolary part” of the Murasaki Shikibu Diary cholars are in agreement on the division of the contents of Murasaki Shikibu nikki (the Murasaki Shikibu Diary, early 11th century) into four dis- Stinct parts. The frst, in the style of a diary (or an ofcial record), presents events from autumn 1008 to the following New Year, focusing on the birth of the future heir to the throne, Prince Atsuhira (1008-1036). -

Murasaki Shikibu: a Reign of One Thousand Years Christine Cousins

Murasaki Shikibu: A Reign of One Thousand Years Christine Cousins Genji, the Shinning Prince, is a master of painting, music, calligraphy, and poetry, and as such would surely have recognized the mastery in Murasaki Shikibu's writing. The success of Murasaki's fictional Tale of Genji over the next thousand years, as demonstrated by the ten thousand books on the subject by the 1960s, cannot simply be the result of the peculiarity of a woman writer.1 Indeed, the evolution of literature during the Heian time period and its connections to Chinese influences contributed to a phenomenon in which woman were the predominant literary producers.2 A component of Genji's success can be attributed to Murasaki's innovative use of literary form through the previously unknown novel, but even one thousand years later, when the novel is not revolutionary, the work is still part of Japanese culture. Murasaki's execution in writing her work is another necessary component to Genji's success, since her skill in portraying the complex interconnections of the Heian period, as well as her plot and characters, underlie the tale’s merit. People have found value in this work for centuries, but Genji's legacy can be distinctly seen in the significance it has accrued in Murasaki's country during times of increasing modernization and Western influence. Translations of the tale into modern Japanese, including those by Yosano Akiko, preserve a national identity, particularly as it relates to literature and culture. Murasaki utilized the opportunities available to her as a woman in the Heian period to create a master work that would, over the course of a thousand years, influence the very form of culture in Japan. -

Rape in the Tale of Genji

SWEAT, TEARS AND NIGHTMARES: TEXTUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN HEIAN AND KAMAKURA MONOGATARI by OTILIA CLARA MILUTIN B.A., The University of Bucharest, 2003 M.A., The University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 ©Otilia Clara Milutin 2015 Abstract Readers and scholars of monogatari—court tales written between the ninth and the early twelfth century (during the Heian and Kamakura periods)—have generally agreed that much of their focus is on amorous encounters. They have, however, rarely addressed the question of whether these encounters are mutually desirable or, on the contrary, uninvited and therefore aggressive. For fear of anachronism, the topic of sexual violence has not been commonly pursued in the analyses of monogatari. I argue that not only can the phenomenon of sexual violence be clearly defined in the context of the monogatari genre, by drawing on contemporary feminist theories and philosophical debates, but also that it is easily identifiable within the text of these tales, by virtue of the coherent and cohesive patterns used to represent it. In my analysis of seven monogatari—Taketori, Utsuho, Ochikubo, Genji, Yoru no Nezame, Torikaebaya and Ariake no wakare—I follow the development of the textual representations of sexual violence and analyze them in relation to the role of these tales in supporting or subverting existing gender hierarchies. Finally, I examine the connection between representations of sexual violence and the monogatari genre itself.