Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murakami-Ego : Collective Culpability and Selective Retention

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2016 Murakami-ego : collective culpability and selective retention. Yun Kweon Jeong Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Contemporary Art Commons Recommended Citation Jeong, Yun Kweon, "Murakami-ego : collective culpability and selective retention." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2497. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2497 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MURAKAMI-EGO: COLLECTIVE CULPABILITY AND SELECTIVE RETENTION By Yun Kweon Jeong B.A. JeonJu University, 1997 M.Div. Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (c) and Art History Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Yun Kweon Jeong All Rights Reserved MURAKAMI-EGO: COLLECTIVE CULPABILITY AND SELECTIVE RETENTION By Yun Kweon Jeong B.A. JeonJu University, 1997 M.Div. Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2008 A Thesis Approved on August 8, 2016 By the following Thesis Committee: Dr. -

Redalyc.Nagasaki. an European Artistic City in Early Modern Japan

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Curvelo, Alexandra Nagasaki. An European artistic city in early modern Japan Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 2, june, 2001, pp. 23 - 35 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100202 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2001, 2, 23 - 35 NAGASAKI An European artistic city in early modern Japan Alexandra Curvelo Portuguese Institute for Conservation and Restoration In 1569 Gaspar Vilela was invited by one of Ômura Sumitada’s Christian vassals to visit him in a fishing village located on the coast of Hizen. After converting the lord’s retainers and burning the Buddhist temple, Vilela built a Christian church under the invocation of “Todos os Santos” (All Saints). This temple was erected near Bernardo Nagasaki Jinzaemon Sumikage’s residence, whose castle was set upon a promontory on the foot of which laid Nagasaki (literal translation of “long cape”)1. If by this time the Great Ship from Macao was frequenting the nearby harbours of Shiki and Fukuda, it seems plausible that since the late 1560’s Nagasaki was already thought as a commercial centre by the Portuguese due to local political instability. Nagasaki’s foundation dates from 1571, the exact year in which the Great Ship under the Captain-Major Tristão Vaz da Veiga sailed there for the first time. -

Noh and Kyogen

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater Noh performance Scene of Hirota Yukitoshi in the noh drama Kagetsu (Flowers and Moon) performed at the 49th Commemorative Noh event. (Photo courtesy of The Nohgaku Performers’ Association) Noh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions forms of classical theater, the other two being were touring and performing at temples, kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its shrines, and festivals, often with the broadest sense includes the comic theater patronage of the nobility. The performing kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical genre called sarugaku was one of these form in the 14th century, making it the oldest traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors extant professional theater in the world. Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami Although noh and kyogen developed together (1363–1443) transformed sarugaku into noh and are inseparable, they are in many ways in basically the same form as it is still exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a performed today. Kan’ami introduced the symbolic theater with primary importance music and dance elements of the popular attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied entertainment kuse-mai into sarugaku, and he aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other attracted the attention and patronage of hand, primary importance is attached to Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu making people laugh. (1358–1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance History of the Noh to further refine the noh aesthetic principles of Theater monomane (the imitation of things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a the suggestion of mystery and depth. -

EDO PRINT ART and ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS Elizabeth R

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: EDO PRINT ART AND ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS Elizabeth R. Nash, Master of Arts, 2004 Thesis directed by: Professor Sandy Kita Department of Art History and Archaeology This thesis focuses on the disparity between the published definitions and interpretations of the artistic and cultural value of Edo prints to Japanese culture by nineteenth-century French and Americans. It outlines the complexities that arise when one culture defines another, and also contrasts stylistic and cultural methods in the field of art history. Louis Gonse, S. Bing and other nineteenth-century European writers and artists were impressed by the cultural and intellectual achievements of the Tokugawa government during the Edo period, from 1615-1868. Contemporary Americans perceived Edo as a rough and immoral city. Edward S. Morse and Ernest Fenollosa expressed this American intellectual disregard for the print art of the Edo period. After 1868, the new Japanese government, the Meiji Restoration, as well as the newly empowered imperial court had little interest in the art of the failed military government of Edo. They considered Edo’s legacy to be Japan’s technological naïveté. EDO PRINT ART AND ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS by Elizabeth R. Nash Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Sandy Kita, Chair Professor Jason Kuo Professor Marie Spiro ©Copyright by Elizabeth R. Nash 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My experience studying art history at the University of Maryland has been both personally and intellectually rewarding. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bk827db Author Chudnow, Matthew Thomas Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

What Genji Paintings Do

Beyond Narrative Illustration: What Genji Paintings Do MELISSA McCORMICK ithin one hundred fifty years of its creation, gold found in the paper decoration of their accompanying cal- The Tale of Genji had been reproduced in a luxurious ligraphic texts (fig. 12). W set of illustrated handscrolls that afforded privileged In this scene from Chapter 38, “Bell Crickets” (Suzumushi II), for readers a synesthetic experience of Murasaki Shikibu’s tale. Those example, vaporous clouds in the upper right corner overlap directly twelfth-century scrolls, now designated National Treasures, with the representation of a building’s veranda. A large autumn survive in fragmented form today and continue to offer some of moon appears in thin outline within this dark haze, its brilliant the most evocative interpretations of the story ever imagined. illumination implied by the silver pigment that covers the ground Although the Genji Scrolls represent a singular moment in the his- below. The cloud patch here functions as a vehicle for presenting tory of depicting the tale, they provide an important starting point the moon, and, as clouds and mist bands will continue to do in for understanding later illustrations. They are relevant to nearly Genji paintings for centuries to come, it suggests a conflation of all later Genji paintings because of their shared pictorial language, time and space within a limited pictorial field. The impossibility of their synergistic relationship between text and image, and the the moon’s position on the veranda untethers the motif from literal collaborative artistic process that brought them into being. Starting representation, allowing it to refer, for example, to a different with these earliest scrolls, this essay serves as an introduction to temporal moment than the one pictured. -

Zen As a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries

Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries by Meng Ying Fan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Meng Ying Fan 2020 Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries Meng Ying Fan Master of Arts Department of East Asia Studies University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This essay explores the impact of Chan/Zen on the art of landscape painting in China and Japan via literary/visual materials from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. By rethinking the aesthetic significance of “Zen painting” beyond the art and literary genres, this essay investigates how the Chan/Zen culture transformed the aesthetic attitudes and technical manifestations of picturing the landscapes, which are related to the philosophical thinking in mind. Furthermore, this essay emphasizes the problems of the “pattern” in Muromachi landscape painting to criticize the arguments made by D.T. Suzuki and his colleagues in the field of Zen and Japanese art culture. Finally, this essay studies the cultural interaction of Zen painting between China and Japan, taking the traveling landscape images of Eight Views of Xiaoxiang by Muqi and Yujian from China to Japan as a case. By comparing the different opinions about the artists in the two regions, this essay decodes the universality and localizations of the images of Chan/Zen. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratefulness to Professor Johanna Liu, my supervisor and mentor, whose expertise in Chinese aesthetics and art theories has led me to pursue my MA in East Asian studies. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

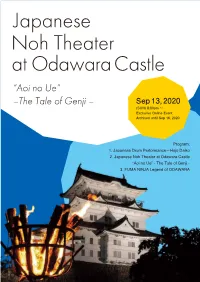

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Portuguese Ships on Japanese Namban Screens

PORTUGUESE SHIPS ON JAPANESE NAMBAN SCREENS A Thesis by KOTARO YAMAFUNE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology Portuguese Ships on Japanese Namban Screens Copyright 2012 Kotaro Yamafune PORTUGUESE SHIPS ON JAPANESE NAMBAN SCREENS A Thesis by KOTARO YAMAFUNE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Luis Filipe Vieira de Castro Committee Members, Kevin J. Crisman Molly Warsh Head of Department, Cynthia Werner August 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT Portuguese Ships on Japanese Namban Screens. (August 2012) Kotaro Yamafune, B.A., Hosei University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Luis Filipe Vieira de Castro Namban screens are a well-known Japanese art form that was produced between the end of the 16th century and throughout the 17th century. More than 90 of these screens survive today. They possess substantial historical value because they display scenes of the first European activities in Japan. Among the subjects depicted on Namban screens, some of the most intriguing are ships: the European ships of the Age of Discovery. Namban screens were created by skillful Japanese traditional painters who had the utmost respect for detail, and yet the European ships they depicted are often anachronistic and strangely. On maps of the Age of Discovery, the author discovered representations of ships that are remarkably similar to the ships represented on the Namban screens.