1 Between Defeat and Victory: Finnish Memory Culture of the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A GUIDE to the ORDERS and DECORATIONS of FINLAND Li'ihi� QIR?[Q)��� 0� Li'ihi� Wihiiitr� �0�� 0� �Iinlan[Q) AN[Q) Li'ihi� Lllon � �Iinlan[Q)

�lUJOMrEN VAll:{Oll�rEN W?lUJlUJ�lUJ N nA �lUJOMrEN l�II nONAN IR?llifAIR?lll:{lUJNN ATr A GUIDE TO THE ORDERS AND DECORATIONS OF FINLAND li'IHI� QIR?[Q)��� 0� li'IHI� WIHIIITr� �0�� 0� �IINlAN[Q) AN[Q) li'IHI� lllON ö� �IINlAN[Q) A GUIDE TO THE ORDERS AND DECORATIONS OF FINLAND Helsinki 2017 Front cover: Grand Crosses of the Orders of the White Rose of Finland and the Lion of Finland Back cover: Adapted from E.F. Wrede, Finlands utmärkelsetecken (Helsingfors 1946) © Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ja Suomen Leijonan ritarikunnat 2017 Layout: Edita Publishing Ltd Illustrations and design: Laura Noponen Photographs: The Orders of the White Rose of Finland and the Lion of Finland, unless otherwise indicated Translation: Foreign Languages Unit, Prime Minister’s Office ISBN 978-951-37-7191-1 Printed by Bookwell Ltd Porvoo 2017 Front cover: Grand Crosses of the Orders of the White Rose of Finland and the Lion of Finland Back cover: Adapted from E.F. Wrede, Finlands utmärkelsetecken (Helsingfors 1946) Sauli Niinistö, President of the Republic of Finland and Grand Master of the Orders of the White Rose of Finland and the Lion of Finland, and Mrs Jenni Haukio. Photograph: Office of the President of the Republic/Matti Porre PREFACE The statutes of the Order of the White Rose of Finland (FWR) were adopted on 16 May 1919. The decorations of the Order are conferred upon citizens who have distinguished themselves in the service of Finland. The Order of the Lion of Finland (FL) was founded by decree (747/1942) during the Second World War, and its dec orations are awarded in recognition of outstanding civilian or military conduct. -

The Finno-Soviet Conflict of 1939-1945 in November 1939 a War Broke out Between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Finl

the Finno-Soviet conflict of 1939-1945 In November 1939 a war broke out between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Finland. The causes of the conflict lay primarily in the world political situation. Germany had already began a war of conquest by invading Poland September first of the same year. Soviet Union sought to protect its borders in view of surging fascist ideas and Germany’s intents to expand. The Soviet Union had primarily wanted to solve the dispute diplomatically before the outbreak of the war. To safeguard itself, the USSR had two aims: First, to move the Finno-Russian border further away from Leningrad, giving Finland a twofold area of land further north along the border in return. Second, to stop any outside force from attacking the Soviet Union through Finnish territories. The Soviets also wanted some certain strategically important areas, including a few islands in the Gulf of Finland in order to prevent a landing to Finland or the Baltics. The suggestions put forward by the Soviet Union were discussed between the states. The Soviet Union was interested in a mutual defense treaty with Finland. The Soviets and Finland would repel an attacker together should they tread on Finland. Representatives from both countries met over half a dozen times, but in the end the offer was refused. The reasons were numerous; the leaders of the state harbored an aggressive “Greater Finnish” ideology that they had fermented within the populace all throughout 1920’s and 30’s. The idea of Greater Finland was based on the goal of incorporating northwestern parts of the Soviet Union into Finland. -

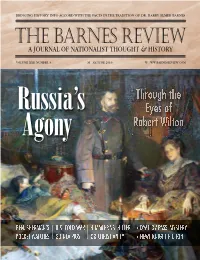

The Barnes Review About the Civil War Is Wrong, a JOURNAL of NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY Ask a Southerner! VOLUME XXII NUMBER 3 M AY/JUNE 2016 W WW.BARNESREVIEW.COM

N E W B O O K F R O M T H E B A R N E S R E V I E W B O O K C L U B . BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES Everything You Were Taught The Barnes Review About the Civil War is Wrong, A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY Ask a Southerner! VOLUME XXII NUMBER 3 M AY/JUNE 2016 W WW.BARNESREVIEW.COM n Everything You Were Taught About the Civil War is Wrong, Ask a Southerner!, award-winning author and his- Did You Know That . torian Lochlainn Seabrook sets the record straight on these • American slavery got its start in the North and hundreds of other commonly misrepresented topics in • Abolition began in the South Ithis easy-to-read, well documented reference book. This • Robert E. Lee was an abolitionist international blockbuster is the book that every Civil War buff has • Only 4.8% of Southerners owned slaves been waiting for! Learn the truth about the war, secession, slavery, • 95.2% of Southerners did not own slaves abolition, the Confederacy, the Union, Jefferson Davis, Abraham • Abraham Lincoln was a White separatist Russia’s Lincoln, Reconstruction, and much more. This • Jefferson Davis adopted a Black boy • Jefferson Davis freed Southern isn’t just a hard-hitting exposé of Yankee myth. slaves before the North Every- thing You Were Taught About the • Lincoln was not against slavery Civil War is Wrong, Ask a Southerner! has the • Lincoln wanted to segregate Blacks power to heal hearts and change minds, for in • The U.S. -

Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 2 July 2015 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-95-4

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S International Influences in Finnish Working-Class Literature and Its Research Guest Editors Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Kati Launis Theme Issue of the Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 2 July 2015 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-95-4 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Titus Hjelm, Lecturer, University College London Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, Institute for Northern Culture, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury George Schoolfield, Professor Emeritus, Yale University Beth L. -

Suomen Ritarikunnat 100 Vuotta

SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT 100 VUOTTA SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT 100 VUOTTA FINLANDS ORDNAR 100 ÅR FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: 100 YEARS FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: 100 YEARS FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: ORDNAR 100 ÅR FINLANDS NÄYTTELY KANSALLISARKISTOSSA 4.12.2018–20.12.2019 UTSTÄLLNING I RIKSARKIVET EXHIBITION AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT 100 VUOTTA FINLANDS ORDNAR 100 ÅR FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: 100 YEARS SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT 100 VUOTTA FINLANDS ORDNAR 100 ÅR FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: 100 YEARS SUOMEN RITARIKUNNAT 100 VUOTTA NÄYTTELY KANSALLISARKISTOSSA 4.12.2018–20.12.2019 FINLANDS ORDNAR 100 ÅR UTSTÄLLNING I RIKSARKIVET 4.12.2018–20.12.2019 FINNISH ORDERS OF MERIT: 100 YEARS EXHIBITION AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES 4 DECEMBER 2018–20 DECEMBER 2019 HELSINKI - HELSINGFORS Kuraattori / Kurator / Curator: PhD Antti Matikkala Ohjausryhmä / Styrgrupp / Steering Group: Pääjohtaja / Generaldirektör /Director General Jussi Nuorteva, puheenjohtaja / ordförande / Chair Kenraaliluutnantti / Generallöjtnant / Lieutenant General Olavi Jäppilä Kontra-amiraali / Konteramiral / Rear Admiral Antero Karumaa Tutkimusjohtaja / Forskningsdirektör / Research Director Päivi Happonen, sihteeri /sekreterare / Secretary Näyttelytyöryhmä / Arbetsgrupp för utställningen / Working Group for the Exhibition: Tutkimusjohtaja Päivi Happonen, puheenjohtaja / ordförande / Chair PhD Antti Matikkala Sisällöntuottaja / Innehållsproducent / Content Producer Wilhelm Brummer Kultaseppämestari / Guldsmedmästare / Master Goldsmith Tuomas Hyrsky Kehittämispäällikkö / Utvecklingschef -

The Image of Marshal Mannerheim, Moral Panic, and the Refashioning of the Nation in the 1990S

CHAPTER 14 The Image of Marshal Mannerheim, Moral Panic, and the Refashioning of the Nation in the 1990s Tuomas Tepora INTRODUCTION The end of the Cold War resulted in radical changes in Finland’s interna- tional position and economy. It sparked an identity struggle, seen within society as soul-searching. One of the major national symbolic fgures, Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867–1951), the Civil War (1918) and World War II military leader and the President of Finland (1944–1946), became a mirror in this collective introspection. This chap- ter addresses the personality cult surrounding Marshal Mannerheim, as well as the alternating images of him, as keys to understanding the emo- tional and social upheavals within Finnish society in the early 1990s. The chapter focuses on the debate in the early 1990s concerning the construction of the Museum of Contemporary Art next to the Mannerheim T. Tepora (*) University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2021 349 V. Kivimäki et al. (eds.), Lived Nation as the History of Experiences and Emotions in Finland, 1800–2000, Palgrave Studies in the History of Experience, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69882-9_14 350 T. TEPORA equestrian statue at the heart of Helsinki. The debate offers invaluable insight into the emotional memory politics, the layers of memories, and future expectations in the post-Cold War nation. In the early 1990s, the Mannerheim statue and contemporary art formed an oxymoron that seemed to threaten the moral base of the nation. The juxtaposition sym- bolized a moral panic that concerned the lived experience of Finland’s changing international position. -

For Peace in Kashmir

THE OBSERVER FOR PEACE IN KASHMIR United Nations Military Observer Group United Nations in India and Pakistan Peace Operations MAGAZINE 2014 2 UNMOGIP MAGAZINE HoM/CMO’s I still remember the anxiety and excitement I felt upon hearing that I was appointed as HoM/CMO to UNMOGIP. Now after more than a year Emphasis and half has passed, I feel very honored to share with you a second edition of the OBSERVER magazine. Unity Throughout the year, the overall situation in UNMOGIP’s Area of National representative Responsibility has remained volatile and delicate with regards to major incidents resulting in a lot of casualties along the LoC. Morality In order to improve the situation, UNMOGIP has actively executed the Openness mandate by enhancing operational plans, SOPs and training programs to conduct and achieve our critical role maintaining peace in this volatile Goal – orientation area by monitoring the ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan. From a support perspective, UNMOGIP is also preparing for Umoja and Impartiality IPSAS which are new UN working systems/standards to upgrade our daily task performance with efficiency and transparency. Professionalism UNMOGIP’s success was only possible by means of our UNMOs in the field as well as international and national staffs’ support and I would like to express a sincere appreciation for the great effort they have made. I’m also grateful to the two hosts-nations and troop contributing countries to the mission: Chile, Croatia, Finland, Italy, Korea, Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, Uruguay and Switzerland and for the assistance of our colleagues in the Department on Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), and last but not the least I would like to express special thanks to our Magazine committee members. -

Paths in Austrian and Finnish History

Smallcons Project A Framework for Socio-Economic Development in Europe? The Consensual Political Cultures of the Small West European States in Comparative and Historical Perspective (No. HPSE-CT-2002-00134) Work Package 10 Paths in Austrian and Finnish History Helmut Konrad, Martin Pletersek, Andrea Strutz (eds.) Department of History/Contemporary History, University of Graz September 2004 Contributors: Helmut Konrad, Martin Pletersek, Johanna Rainio-Niemi, Henrik Stenius, Andrea Strutz 2 Contents Helmut Konrad, Martin Pletersek, Andrea Strutz Paths in Austrian and Finnish history – a tentative comparison Helmut Konrad Periods in the History of Austrian Consensualism Henrik Stenius Periodising Finnish Consensus Martin Pletersek, Andrea Strutz A Monarchy and Two Republics – the Austrian Path (including comparative context of neighbouring new EU-members) Johanna Rainio-Niemi Paths in the Austrian and Finnish history: FINLAND (including comparative context of neighbouring new EU-members) 3 Paths in Austrian and Finnish history – a tentative comparison Helmut Konrad, Martin Pletersek, Andrea Strutz The smallcons-project "A Framework for Socio-economic Development in Europe? The Consensual Political Cultures of the Small West European States in Comparative and Historical Perspective" reserves a particular place for Austria and Finland because "[…] these cases suggest that the communication capacity conditional for consensualism can emerge within only a few decades." (Annex to the contract: 3). As opposed to the other project countries, the project proposal assumes that the two are the discontinuity cases whose historical paths didn't seem to point towards consensualism. In the words of Peter Katzenstein, "[…] the Austrian train was at every branch switched in a direction opposite from the other small European states." (1985: 188). -

FINLANDS LINJE © Paavo Väyrynen Och Kustannusosakeyhtiö Paasilinna 2014

Paavo Väyrynen FINLANDS LINJE © Paavo Väyrynen och Kustannusosakeyhtiö Paasilinna 2014 Omslag: Laura Noponen ISBN 978-952-299-055-6 TILL LÄSAREN Under de senaste åren har jag sökt fördjupa mig i historien – såväl i händelser i det förgångna som i historieskrivning. Min första tidsresa hänger samman med Kemi stads åldringshem Niemi-Niemelä som vi köpte 1998. Jag skrev om det i boken Pohjanranta som utkom 2005. Verket har starka kopplingar till olika skeden i Norra bottens och hela Finlands utveckling. Min andra tidsresa gick till skeden knutna till min egen släkt. När min far fyllde 100 år i januari 2010 skrev jag en bok om honom – Eemeli Väyrysen vuosisata (Eemeli Väyrynens århundrade). Jag studerade min släkts rötter så långt dokumenten sträckte sig. Också detta arbete öppnade perspektiv på både min hembygds och hela landets historia. I min senaste bok Huonomminkin olisi voinut käydä (Det kunde också ha gått sämre) tillämpade jag en kontrafaktuell historieskrivningsmetod på mitt eget liv och min verksamhet. Jag funderade på hur det kunde ha gått om något avgörande gjorts på annat sätt. Denna granskningsmetod har sitt berättigande då beslut i praktiken ofta fattas som val mellan olika alternativ. Speciellt inom den ekonomiska historien kan 5 man i efterhand bedöma visheten i gjorda beslut. Inom politisk historia har kontrafaktuella metoder brukats i liten utsträckning. Detta är märkligt då beslut ofta fattas genom omröstning och ibland med knapp majoritet. I efterhand vore det klokt att fundera på vilken utvecklingen blivit med en alternativ lösning. Även i beslutsfattande som riktar sig framåt i tiden borde ett kontrafaktualt grepp finnas med. -

Markkinatalouden Etujoukot

Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto MARKKINATALOUDEN ETUJOUKOT Elinkeinoelämän valtuuskunta, Teollisuuden keskusliitto ja liike-elämän poliittinen toiminta 1970–1980-lukujen Suomessa Maiju Wuokko Väitöskirja Esitetään Helsingin yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi auditoriumissa XII perjantaina 30. syyskuuta 2016 klo 12. Helsinki 2016 Historiallisia tutkimuksia Helsingin yliopistosta 41 ISSN 2342-0138 ISBN 978-951-51-2455-5 (pbk.) ISBN 978-951-51-2456-2 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Kansikuva on Kaarlo A. Rissasen (Käntsin) pilapiirros Kauppalehdestä 5.12.1980. Julkaistu Kauppalehden luvalla. “An invasion of armies can be resisted; an invasion of ideas cannot be resisted.” Victor Hugo1 ”Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.” Milton Friedman2 ”Pyrkiessään muuttamaan yhteiskuntaa teollisuuden olisi otettava huomioon olevat olosuhteet: vesi ei virtaa ylämäkeen. Silti tähän ei saa alistua. On maanalaisia voimia, jotka muovaavat maastoa. Ne saattavat synnyttää jopa uusia vuoristoja ja kyllä vesi sitten virtaa niiden mukaan.” Gustav von Hertzen3 1 Hugo, Victor (1877) The History of a Crime: The testimony of an eye-witness. Kääntäneet Joyce, T. H. & Locker, Arthur. 368. Project Gutenberg -internetsivusto. 2 Milton Friedman (1962/1982) Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. viii-ix. Teos on ilmestynyt alun perin 1962. Lainaus on vuoden 1982 laitoksen esipuheesta. 3 KA. EVA. Kauko Sipponen 1977–1990. Muistio ‘Teollisuuden keskusvaliokunnan suunnitteluryhmän ideapalaveri’, Aavaranta 11.-12.6.1984. -

Finnish Studies

JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES Volume 16 Number 2 May 2013 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1402; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Associate Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Assistant Editor, University of Wisconsin; [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University, Toronto Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University, New York Anselm Hollo, Professor, Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of -

On War and the Winter War Robert Karnisky

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 On War and the Winter War Robert Karnisky Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ON WAR AND THE WINTER WAR by Robert Karnisky A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Robert B. Karnisky defended on June 29, 2007. ________________________ Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Thesis ________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ________________________ James P. Jones Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my committee. These include my graduate professor, Dr. Jonathan Grant, for his advice during the writing of this work, his entertaining lectures, and especially for his patience; Dr. Michael Creswell, for introducing me to military affairs and for encouraging me to pursue this topic; and Dr. James P. Jones, for his continued interest in my academic progress, and for his fifty years of teaching at Florida State. The remaining members of the faculty and staff at FSU deserve recognition for too many reasons to be recounted here – but most of all for making my experience here so enjoyable. Rarely does someone in my circumstance receive the opportunity I have been given, and I will never forget the people who made it such a positive one.