The Development of Small Christian Communities in the Catholic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Self-Settled Refugees and the Impact on Service Delivery in Koboko

Self-Settled Refugees and the Impact on Service Delivery in Koboko Municipal Council Empowering Refugee Hosting Districts in Uganda: Making the Nexus Work II2 Empowering Refugee Hosting Districts in Uganda: Making the Nexus Work Foreword This report ‘Self-Settled Refugees and the Impact on Service Delivery in Koboko Municipal Council’ comes in a time when local governments in Uganda are grappling with the effects of refugees who have moved and settled in urban areas. As a country we have been very welcoming to our brothers and sisters who have been seeking refuge and we are proud to say that we have been able to assist the ones in need. Nonetheless, we cannot deny that refugees have been moving out of the gazetted settlements and into the urban areas, which has translated into increasing demands on the limited social amenities and compromises the quality of life for both refugees and host communities, this whilst the number of self-settled refugees continues to grow. This report aims to address the effects the presence self-settled refugees have on urban areas and the shortfalls local governments face in critical service delivery areas like education, health, water, livelihoods and the protection of self-settled refugees if not properly catered for. So far, it has been difficult for the local governments to substantiate such cases in the absence of reliable data. We are therefore very pleased to finally have a reference document, which addresses the unnoticed and yet enormous challenges faced by urban authorities hosting refugees, such as Koboko Municipal Council. This document provides us with more accurate and reliable data, which will better inform our planning, and enhances our capacity to deliver more inclusive services. -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Rcdf Projects in Yumbe District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN YUMBE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F YU M B E SH O W IN G S UB C O U NT IE S N Midigo Kei Apo R omo gi Yum be TC Kuru D rajani Od ravu 3 0 3 6 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Yumbe district………….………..….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Yumbe district………..………………….………...………….14 10- Map of Yumbe district showing sub counties………..……………………………….15 11- Table showing the population of Yumbe district by sub counties……..…...15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Yumbe district…………………………………….………...…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Rural Electrification Agency ENERGY FOR RURAL TRANSFORMATION PHASE III GRID INTENSIFICATION SCHEMES PACKAGED UNDER WEST NILE, NORTH NORTH WEST, AND NORTHERN SERVICE TERRITORIES Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE, 2019 i LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDO Community Development Officer CFP Chance Finds Procedure DEO District Environment Officer ESMP Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Plan ESMF Environmental Social Management Framework ERT III Energy for Rural Transformation (Phase 3) EHS Environmental Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESMMP Environmental and Social Mitigation and Management Plan GPS Global Positioning System GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism MEMD Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development NEMA National Environment Management Authority OPD Out Patient Department OSH Occupational Safety and Health PCR Physical Cultural Resources PCU Project Coordination Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment REA Rural Electrification Agency RoW Right of Way UEDCL Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited WENRECO West Nile Rural Electrification Company ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... -

CARE for PEOPLE LIVING with DISABILITIES in the WEST NILE REGION of UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009

CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009 CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA: EX-POST EVALUATION OF A PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTED BY DOCTORS WITH AFRICA CUAMM Maria-Pia Waelkens#, Everd Maniple and Stella Regina Nakiwala, Faculty of Health Sciences, Uganda Martyrs University, P.O. Box 5498 Kampala, Uganda. #Corresponding author e-mail addresses: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Disability is a common occurrence in many countries and a subject of much discussion and lobby. People with disability (PWD) are frequently segregated in society and by-passed for many opportunities. Stigma hinders their potential contribution to society. Doctors with Africa CUAMM, an Italian NGO, started a project to improve the life of PWD in the West Nile region in north- western Uganda in 2003. An orthopaedic workshop, a physiotherapy unit and a community-based rehabilitation programme were set up as part of the project. This ex-post evaluation found that the project made an important contribution to the life of the PWD through its activities, which were handed over to the local referral hospital for continuation after three years. The services have been maintained and their utilisation has been expanded through a network of outreach clinics. Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers mobilise the community for disability assessment and supplement the output of qualified health workers in service delivery. However, the quality of care during clinics is still poor on account of large numbers. In the face of the departure of the international NGO, a new local NGO has been formed by stakeholders to take over some functions previously done by the international NGO, such as advocacy and resource mobilisation. -

Ministry of Finance Pages New.Indd

x NEW VISION, Wednesday, August 1, 2012 ADVERT MINISTRY OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FIRST QUARTER (JULY - SEPTEMBER 2012) USE CAPITATION RELEASE BY SCHOOL BY LOCAL GOVERNMENT VOTES FOR FY 2012/13 (USHS 000) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA District School Name Account Title A/C No. Bank Branch Quarter 1 Release District School Name Account Title A/C No. Bank Branch Quarter 1 Release S/N Vote Code S/N Vote Code 9 562 KIRUHURA KAARO HIGH SCHOOL KAARO HIGH SCHOOL 0140053299301 Stanbic Bank Uganda MBARARA 9,020,000 4 571 BUDAKA NGOMA STANDARD SCH. NGOMA STANDARD SCH. 0140047863601 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 36,801,000 10 562 KIRUHURA KIKATSI SEED SECOND- KIKATSI SEED SECONDARY 95050200000573 Bank Of Baroda MBARARA 7,995,000 5 571 BUDAKA KADERUNA S.S KADERUNA S.S 0140047146701 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 21,311,000 ARY SCHOOL SCHOOL 6 571 BUDAKA KAMERUKA SEED KAMERUKA SEED SECOND- 3112300002 Centenary Bank MBALE 10,291,000 11 562 KIRUHURA KINONI COMMUNITY HIGH KINONI COMMUNITY HIGH 1025140340474 Equity Bank RUSHERE 17,813,000 SECONDARY SCHOOL ARY SCHOOL SCHOOL SCHOOL 7 571 BUDAKA LYAMA S.S LYAMA SEN.SEC.SCH. 3110600893 Centenary Bank MBALE 11,726,000 12 562 KIRUHURA SANGA SEN SEC SCHOOL SANGA SEC SCHOOL 5010381271 Centenary Bank MBARARA 11,931,000 8 571 BUDAKA NABOA S.S.S NABOA S.S.S 0140047144501 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 20,362,000 Total 221,620,000 9 571 BUDAKA IKI IKI S.S IKI-IKI S.S 0140047145501 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 40,142,000 - 10 571 BUDAKA IKI IKI HIGH SCHOOL IKI IKI HIGH SCHOOL 01113500194316 Dfcu Bank MBALE 23,171,000 -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak Minihydro

FILE Coey 5 Public Disclosure Authorized Report /02 Environmental Public Disclosure Authorized Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro (Revised v.2) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ECON-Report no. /02, Project no. 36200 <Velg tilgjengelighet> ISSN: 0803-5113, ISBN 82-7645-xxx-x e/,, 9. January 2003 Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro Commissioned by West Nile Concession Committee Prepared by EMA & ECON ECON Centre for Economic Analysis P.O.Box 6823 St. Olavs plass, 0130 Oslo, Norway. Phone: + 47 22 98 98 50, Fax: + 47 22 11 00 80, http://www.econ.no - EMA & ECON - Environmental Impact Statement for Nyagak minihydro 4.3 Geologic Conditions .............. 26 4.4 Project Optimisation .............. 26 4.5 Diversion Weir and Fore bay .............. 27 4.6 Regulating Basin and Penstock .............. 28 4.7 Powerhouse .............. 28 5 EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE . ............................30 5.1 Physical Environment .............................. 30 5.1.1 Climate and Weather Patterns .............................. 30 5.1.2 Geomorphology, geology and soils .............................. 30 5.1.3 Hydrology .............................. 32 5.1.4 Seismology .............................. 32 5.2 Vegetation .............................. 33 5.3 Wildlife .............................. 34 5.3.1 Mammals .............................. 34 5.3.2 Birds .............................. 34 5.3.3 Fisheries .............................. 34 5.3.4 Reptiles .............................. 35 5.4 Socio-economics -

REPUBLIC of UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY

E1879 VOL.3 REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY FINAL DETAILED ENGINEERING Public Disclosure Authorized DESIGN REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN FOR UPGRADING TO PAVED (BITUMEN) STANDARD OF VURRA-ARUA-KOBOKO-ORABA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized VOL IV - ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized The Executive Director Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Plot 11 Yusuf Lule Road P.O.Box AN 7917 P.O.Box 28487 Accra-North Kampala, Uganda Ghana Feasibility Study and Detailed Design ofVurra-Arua-Koboko-Road Environmental Social Impact Assessment Final Detailed Engineering Design Report TABLE OF CONTENTS o EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 0-1 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ROAD........................................................................................ I-I 1.3 NEED FOR AN ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDy ...................................... 1-3 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE ESIA STUDY ............................................................................................... 1-3 2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 INITIAL MEETINGS WITH NEMA AND UNRA............................................................................ -

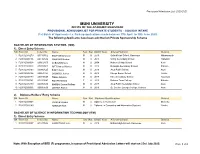

Applicants 2020/2021 AUGUST

Provisional Admission List- 2020/2021 MUNI UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR PROVISIONAL ADMISSION LIST FOR PRIVATE STUDENTS - 2020/2021 INTAKE (1st Batch of Applicants- i.e. Paid-up applications made between 17th April to 30th June 2020) The following Applicants have been admitted on Private Sponsorship Scheme BACHELOR OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS (ISM) 1). Direct Entry Scheme SN Form ID Index No Name Sex Nat UACE Year A' level School District 1 F20012000270 U1711/502 SEMPUNGU Jovan M U 2019 Oxford High School, Kawempe Nakasongola 2 F20012000146 U0136/532 ONWANG Nathan M U 2014 Uringi Secondary School Pakwach 3 F20012000068 U0062/605 ACELUN Moses M U 2004 Nabumali High School Kumi 4 F20012000028 U0874/501 GIFT Samuel Moses M U 2019 Nyangilia Secondary School Koboko 5 F20012000193 U0090/625 EJOYI Denis M U 2019 Arua Public School Arua 6 F20012000136 U0053/727 OKONGO Joshua M U 2019 Mengo Senior School Tororo 7 F20012000133 U0288/549 TABO Jackson M U 2019 Metu Secondary School Adjumani 8 F20012000261 U1632/542 ROPAN Monika F U 2019 Koboko Town College Koboko 9 F20012000139 U0090/618 MAMBO Darwin Rollings M U 2017 Arua Public Secondary School Arua 10 F20012000016 U0035/536 ONZIMA Robert M U 2019 St. Charles Lwanga College, Koboko Arua 2). Diploma Holders' Entry Scheme SN Form ID Name Sex Nat. Diploma Qualification District 1 F20012000048 VIGOUR Ronald M U Diploma in Horticulture Maracha 2 F20012000149 ADRIKOTITUS M U Diploma in Computing and Information Systems Yumbe BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (ITM) 1). Direct Entry Scheme SN Form ID Index No Name Sex Nat UACE Year A' level School District 1 F20012000057 U1611/584 AGANI Daniel Iyete M U 2019 Brilliant High School - Kawempe Arua Note: With Exception of BED (P) programme, issuance of Provisional Admission Letters will start on 23rd July 2020.