Self-Settled Refugees and the Impact on Service Delivery in Koboko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Rural Electrification Agency ENERGY FOR RURAL TRANSFORMATION PHASE III GRID INTENSIFICATION SCHEMES PACKAGED UNDER WEST NILE, NORTH NORTH WEST, AND NORTHERN SERVICE TERRITORIES Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE, 2019 i LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDO Community Development Officer CFP Chance Finds Procedure DEO District Environment Officer ESMP Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Plan ESMF Environmental Social Management Framework ERT III Energy for Rural Transformation (Phase 3) EHS Environmental Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESMMP Environmental and Social Mitigation and Management Plan GPS Global Positioning System GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism MEMD Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development NEMA National Environment Management Authority OPD Out Patient Department OSH Occupational Safety and Health PCR Physical Cultural Resources PCU Project Coordination Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment REA Rural Electrification Agency RoW Right of Way UEDCL Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited WENRECO West Nile Rural Electrification Company ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... -

Ministry of Finance Pages New.Indd

x NEW VISION, Wednesday, August 1, 2012 ADVERT MINISTRY OF FINANCE, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FIRST QUARTER (JULY - SEPTEMBER 2012) USE CAPITATION RELEASE BY SCHOOL BY LOCAL GOVERNMENT VOTES FOR FY 2012/13 (USHS 000) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA District School Name Account Title A/C No. Bank Branch Quarter 1 Release District School Name Account Title A/C No. Bank Branch Quarter 1 Release S/N Vote Code S/N Vote Code 9 562 KIRUHURA KAARO HIGH SCHOOL KAARO HIGH SCHOOL 0140053299301 Stanbic Bank Uganda MBARARA 9,020,000 4 571 BUDAKA NGOMA STANDARD SCH. NGOMA STANDARD SCH. 0140047863601 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 36,801,000 10 562 KIRUHURA KIKATSI SEED SECOND- KIKATSI SEED SECONDARY 95050200000573 Bank Of Baroda MBARARA 7,995,000 5 571 BUDAKA KADERUNA S.S KADERUNA S.S 0140047146701 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 21,311,000 ARY SCHOOL SCHOOL 6 571 BUDAKA KAMERUKA SEED KAMERUKA SEED SECOND- 3112300002 Centenary Bank MBALE 10,291,000 11 562 KIRUHURA KINONI COMMUNITY HIGH KINONI COMMUNITY HIGH 1025140340474 Equity Bank RUSHERE 17,813,000 SECONDARY SCHOOL ARY SCHOOL SCHOOL SCHOOL 7 571 BUDAKA LYAMA S.S LYAMA SEN.SEC.SCH. 3110600893 Centenary Bank MBALE 11,726,000 12 562 KIRUHURA SANGA SEN SEC SCHOOL SANGA SEC SCHOOL 5010381271 Centenary Bank MBARARA 11,931,000 8 571 BUDAKA NABOA S.S.S NABOA S.S.S 0140047144501 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 20,362,000 Total 221,620,000 9 571 BUDAKA IKI IKI S.S IKI-IKI S.S 0140047145501 Stanbic Bank Uganda PALLISA 40,142,000 - 10 571 BUDAKA IKI IKI HIGH SCHOOL IKI IKI HIGH SCHOOL 01113500194316 Dfcu Bank MBALE 23,171,000 -

Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in Two Refugee Settlements of Uganda

X Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda X Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda Copyright © International Labour Organization 2021 First published 2021 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publishing (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The ILO and FAO welcome such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda ISBN 978-92-2-034720-1 (Print) ISBN 978-92-2-034719-5 (Web PDF) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Seed System Security Assessment in West Nile Sub Region (Uganda)

Seed System Security Assessment in West Nile Sub region April 2015 Integrated Seed Sector Development Programme Uganda Seed System Security Assessment in West Nile Sub-region Integrated Seed Sector Development Programme In Uganda Recommended referencing: ISSD Uganda, 2015. Seed System Security Assessment in West Nile Sub-region. Integrated Seed Sector Development Programme in Uganda, Wageningen UR Uganda. Kampala Participating partners: FAO (Nairobi), Danish Refugee Council, ZOA, NilePro Trust Limited and Local Governments of Arua, Koboko, Adjumani and Moyo District TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................. i ACKOWLEDGEMENT ........................................................................................... ii THE ASSESSMENT TEAM ..................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND TO THE SEED SECURITY ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................... 1 1.2 ASSESSMENT OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................................... -

Survey Highlights on Self-Settled Refugees in Koboko Municipal

Survey Highlights on Self-Settled Refugees in Koboko Municipal Council Empowering Refugee Hosting Districts in Uganda: Making the Nexus Work Introduction to the Survey This report presents the Highlights of the household survey conducted on Self-Settled Refugees in Koboko Municipal Council (July- August 2018), as part of the Programme “Strengthening Refugee Hosting Districts in Uganda: Making the Nexus Work”. The programme is implemented by VNG International (the international cooperation agency of the Association of Netherlands Municipalities) and financed by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Koboko District Local Government is one of the beneficiaries within the programme, along with Adjumani and Yumbe District Local Governments. The Uganda Local Government Association (ULGA) is a key partner in this programme. The survey was premised on the fact that in Koboko Municipal Council the presence of self-settled refugees puts a lot of strain on the already stressed service delivery and is posing significant challenges to the local government. Some of the notable challenges include: conflicts with the law, rampant cases of child neglect and abuse, prostitution, theft and armed robberies and conflicts with the host communities over natural resources and food scarcity. Besides the above, the host communities are grappling with a strain on healthcare provision, congestion in schools and at water points, poor waste management and sanitation, scarcity of housing and rising prices of goods and services. The presence of self-settled refugees has not been provided for in the district and municipal budgeting process, given that census data 2014 serve as a basis for planning and therefore no additional funding is guaranteed by the government and development partners. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

REPUBLIC of UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY

E1879 VOL.3 REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY FINAL DETAILED ENGINEERING Public Disclosure Authorized DESIGN REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN FOR UPGRADING TO PAVED (BITUMEN) STANDARD OF VURRA-ARUA-KOBOKO-ORABA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized VOL IV - ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized The Executive Director Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Plot 11 Yusuf Lule Road P.O.Box AN 7917 P.O.Box 28487 Accra-North Kampala, Uganda Ghana Feasibility Study and Detailed Design ofVurra-Arua-Koboko-Road Environmental Social Impact Assessment Final Detailed Engineering Design Report TABLE OF CONTENTS o EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 0-1 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ROAD........................................................................................ I-I 1.3 NEED FOR AN ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDy ...................................... 1-3 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE ESIA STUDY ............................................................................................... 1-3 2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 INITIAL MEETINGS WITH NEMA AND UNRA............................................................................ -

ARUA BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2014/15 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Foreword Am delighted to present the Arua District Local Government Budget Framework Paper for Financial Year 2014/15. the Local Government Budget framework paper has been prepared with the collaboration and participation of members of the District Council, Civil Society Organozations and Lower Local Governments and other stakeholders during a one day budgtet conference held on 14th September 2013. The District Budget conferences provided an opportujity to intergrate the key policy issues and priorities of all stakeholders into the sectoral plans. The BFP represents the continued commitment of the District in joining hands with the Central Government to promote Growth, Employment and Prosperity for financial year 2014/15 in line with the theme of the National Development Plan. This theme is embodied in our District vision of having a healthy, productive and prosperious people by 2017. The overall purpose of the BFP is to enable Arua District Council, plan and Budget for revenue and expenditure items within the given resoruce envelop. Local Revenue, Central Government Transfers and Donor funds, finance the short tem and medium tem expenditure frame work. The BFP raises key development concerns for incorporation into the National Budget Framework Paper. The BFP has been prepared in three main sections. It has taken into account the approved five year development plan and Local Economic Development Strategy. -

Implementation Status & Results

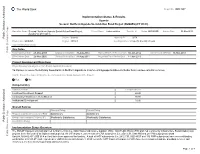

The World Bank Report No: ISR13907 Implementation Status & Results Uganda Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project (NUSAF2) (P111633) Operation Name: Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 03-May-2014 (NUSAF2) (P111633) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Uganda Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 28-May-2009 Original Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Jan-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 19-Nov-2013 Effectiveness Date 25-Nov-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 14-Jun-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To improve access of beneficiary households in Northern Uganda to income earning opportunities and better basic socio-economic services. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Livelihood Investment Support 60.00 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation 30.00 Institutional Development 10.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview The NUSAF II project originally planned to finance 9750 (i.e. 8000 Household Income Support (HIS), 1000 Public Works (PW) and 750 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation) sub projects in the five year of its implementation period. As of February 3, 2013 a total of 8,764 subprojects (i.e. -

Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, and the International Business Commons Recommended Citation Cowans, Aaron, "Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1226. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1226 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Performance Measurement and Improvement at FINCA Uganda Aaron Cowans SIT Uganda: Microfinance and Entrepreneurship Academic Advisor: Godfrey Byekwaso Academic Director: Martha Wandera Fall 2011 Dedication This work is dedicated to my family in America and the amazing people I have met here in Uganda, who have all helped me throughout my journey. 2 Acknowledgements While so many people helped me along my way, I want to acknowledge the following people in particular who were instrumental to my experience here. Martha Wandera, Helen Lwemamu and the rest of the SIT staff for putting together such a fantastic program. I have learned so much here and made memories which will last a lifetime. This was all possible because of your constant hard work and dedication. All of the staff at FINCA Uganda and FINCA International who so graciously hosted me as an intern and supported me through the duration of my internship. -

S41018-021-00105-8.Pdf

Bako et al. Journal of International Humanitarian Action (2021) 6:17 Journal of International https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-021-00105-8 Humanitarian Action RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Towards attaining the recommended Humanitarian Sphere Standards of sanitation in Bidibidi refugee camp found in Yumbe District, Uganda Zaitun Bako1, Alex Barakagira1,2* and Ameria Nabukonde1 Abstract Adequate sanitation is one of the most important aspects of community well-being. It reduces the rates of morbidity and severity of various diseases like diarrhea, dysentery, and typhoid among others. A study about toward the attainment of the recommended Humanitarian Sphere Standards on sanitation in Bidibidi refugee camp, Yumbe District, was initiated. A total of 210 households distributed in Bidibidi refugee camp were randomly selected and one adult person interviewed to assess the accessibility of different sanitation facilities, and to explore the sanitation standards of the sanitation facilities in relation to the recommended Humanitarian Sphere Standards in the area. Pit latrines, hand washing facilities, and solid waste disposal areas as reported by 81.4%, 86.7%, and 51.9% of the respondents respectively, are the main sanitation facilities accessed in the refugee camp. Despite their accessibility, the standards of the pit latrines, hand washing, and solid waste disposal facilities are below the recommended standards, which might have contributed to the outbreak of sanitation related diseases (χ2 = 19.66, df = 1, P = 0.05) in Bidibidi refugee camp. The respondents in the study area were aware that the presence of the sanitation-related diseases was because of the low-level sanitation practices in place (χ2 = 4.54, df = 1, P = 0.05).