Poprasit 4119 Copy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Laos, Known As the “Land of a Million Elephants,” Is a Landlocked Country in Southeast Asia About the Size of Kansas

DO NOT COPY WITHOUT PERMISSION OF AUTHOR Simon J. Bronner, ed. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AMERICAN FOLKLIFE. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. Rachelle H. Saltzman, Iowa Arts Council, Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs [email protected] LAO Laos, known as the “Land of a Million Elephants,” is a landlocked country in Southeast Asia about the size of Kansas. The elephant symbolizes the ancient kingdom of Lan Xang, and is sacred to the Lao people, who believe it will bring prosperity to their country. Bordered by China to the north, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the south, Thailand to the west, and Myanmar (formerly Burma) to the northwest, Laos is a rough and mountainous land interwoven with forests and plateaus. The Mekong River, which runs through the length of Laos and supplies water to the fertile plains of the river basin, is both symbolically and practically, the lifeline of the Lao people, who number nearly 6 million. According to Wayne Johnson, Chief for the Iowa Bureau of Refugee Services, and a former Peace Corps Volunteer, “the river has deep meaning for the ethnic Lao who are Buddhist because of the intrinsic connection of water with the Buddhist religion, a connection that does not exist for the portion of the population who are non-ethnically Lao and who are animists.” Formally known as the Kingdom of Laos, and now known as Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Laos was, in previous centuries, periodically independent and periodically part of the Khmer (Cambodian), Mongol, Vietnamese, and Thai (Siamese) empires. Lao, Thai, and Khmer (but not Vietnamese) share a common heritage evident today in similar religion, music, food, and dance traditions as well as language and dress. -

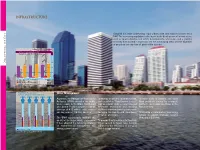

Infrastructure

INFRASTRUCTURE Bangkok has been undergoing rapid urbanization and industrialization since 1960. The increasing population is due in part to the development of infrastructure, such as road networks, real estate developments, land value, and a growing economy that resulted in expansion into the surrounding areas and the migration of people to the city from all parts of the country. 7>ÌiÀÊ ÃÕ«ÌÊÊ >}Ê>`Ê6VÌÞÊÀi> Õ°° Discovering the City the Discovering City the Discovering xxÈ°Ó Èää x£È°Ó xän°£ {nÈ°Î {n°È {ÇÈ°Ç {ää Óää ££°Ç È°{ n°£ ä ÓääÓ ÓääÎ Óää{ , - / *1 Ê7/ ,Ê-1**9Ê Ê"/ ,- 1- --]Ê-// Ê / ,*,- ]Ê"6¿/Ê 9Ê Ê 1-/, Source: Metropolitan Waterworks Authority /Ì>Ê7>ÌiÀÊ*À`ÕVÌÊÉÊ Water Management ->iÃÊÊ >}Ê>`Ê6VÌÞÊÀi> At present, the Metropolitan Waterworks To develop an effl uent treatment system, To build walls to prevent and solve Authority (MWA) provides the public and establish a “Flood Control Center” fl ood problems caused by seasonal, water supply in the BMA, Nonthaburi with 55 network stations, using low-cost northern and marine overfl ows in the and Samut Prakarn provinces at an treatment techniques and building Bangkok area. Ê Õ°° average of 4.15 million cubic meters additional water treatment systems, while Ó]äää per day, over a 1,486.5 sq. km area. restoring the beauty and cleanliness To develop an information technology £]xÎn°Î £]xää £]xäx £]x£È°£ of canals and rivers. system to support drainage systems £]{n£°Ç £]{În°x £]äÇÈ The BMA continuously monitors the throughout Bangkok. £]äää È°{ £]ä£Î° Ó°x nnä°Î quality of the water supply and canals. -

Mon Affairs Union Representative: Nai Bee Htaw Monzel

Mon Affairs Union Representative: Nai Bee Htaw Monzel Mr. Chairman or Madame Chairperson I would like to thank you for giving me the opportunity to participate in the Forum. I am representative from the Mon Affairs Union. The Mon Affairs Union is the largest Mon political and social organization in Mon State. It was founded by Mon organizations both inside and outside Burma in 2008. Our main objective to restore self-determination rights for Mon people in Burma. Mon people is an ethnic group and live in lower Burma and central Thailand. They lost their sovereign kingdom, Hongsawatoi in 1757. Since then, they have never regained their self- determination rights. Due to lack of self-determination rights, Mon people are barred from decision making processes on social, political and economic policies. Mon State has rich natural resources. Since the Mon do not have self-determination rights, the Mon people don’t have rights to make decision on using these resources. Mon State has been ruled by Burmese military for many years. Burmese military government extracts these resources and sells to neighboring countries such as China and Thailand. For example, the government sold billions of dollars of natural gas from Mon areas to Thailand. Instead of investing the income earned from natural gas in Mon areas, the government bought billion dollars of arms from China and Russia to oppress Mon people. Due Burmese military occupation in Mon areas, livelihoods of Mon people economic life have also been destroyed. Since 1995, Burmese military presence in Mon areas was substantially increased. Before 1995, Burma Army had 10 battalions in Mon State. -

THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK

ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK N I H T O DUSIT AY EXP Y THANON L RE O SSWA H PHR 5 A H A PINKL P Y N A PRESSW O O N A EX H T Thonburi Democracy Station Monument 2 THAN BANGLAMPHU ON PHE 1 TC BAMRUNG MU HABURI C ANG h AI H 4 a T o HANO CHAROEN KRUNG N RA (N Hualamphong MA I EW RAYAT P R YA OAD) Station T h PAHURAT OW HANON A PL r RA OENCHI THA a T T SU 3 SIAM NON NON PH KH y a SQUARE U CHINATOWN C M HA H VIT R T i v A E e R r X O P E N R 6 K E R U S N S G THAN DOWNTOWN W A ( ON RAMABANGKOK IV N Y E W M R LO O N SI A ANO D TH ) 0 1 km TAKSIN BRI DGE 1 Ratanakosin 3 Chinatown and Pahurat 5 Dusit 2 Banglamphu and the 4 Thonburi 6 Downtown Bangkok Democracy Monument area About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The colour section is designed to give you a feel for Bangkok, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The city chapters cover each area of Bangkok in depth, giving comprehensive accounts of all the attractions plus excursions further afield, while the listings section gives you the lowdown on accommodation, eating, shopping and more. -

Late Jomon Male and Female Genome Sequences from the Funadomari Site in Hokkaido, Japan

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 127(2), 83–108, 2019 Late Jomon male and female genome sequences from the Funadomari site in Hokkaido, Japan Hideaki KANZAWA-KIRIYAMA1*, Timothy A. JINAM2, Yosuke KAWAI3, Takehiro SATO4, Kazuyoshi HOSOMICHI4, Atsushi TAJIMA4, Noboru ADACHI5, Hirofumi MATSUMURA6, Kirill KRYUKOV7, Naruya SAITOU2, Ken-ichi SHINODA1 1Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba City, Ibaragi 305-0005, Japan 2Division of Population Genetics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima City, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan 3Department of Human Genetics, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan 4Department of Bioinformatics and Genomics, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa City, Ishikawa 920-0934, Japan 5Department of Legal Medicine, Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, University of Yamanashi, Chuo City, Yamanashi 409-3898, Japan 6Second Division of Physical Therapy, School of Health Sciences, Sapporo Medical University, Sapporo City, Hokkaido 060-0061, Japan 7Department of Molecular Life Science, School of Medicine, Tokai University, Isehara City, Kanagawa 259-1193, Japan Received 18 April 2018; accepted 15 April 2019 Abstract The Funadomari Jomon people were hunter-gatherers living on Rebun Island, Hokkaido, Japan c. 3500–3800 years ago. In this study, we determined the high-depth and low-depth nuclear ge- nome sequences from a Funadomari Jomon female (F23) and male (F5), respectively. We genotyped the nuclear DNA of F23 and determined the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class-I genotypes and the phenotypic traits. Moreover, a pathogenic mutation in the CPT1A gene was identified in both F23 and F5. The mutation provides metabolic advantages for consumption of a high-fat diet, and its allele fre- quency is more than 70% in Arctic populations, but is absent elsewhere. -

“White Elephant” the King's Auspicious Animal

แนวทางการบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีนส าหรับโรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) สังกัดกรุงเทพมหานคร ประกอบด้วยองค์ประกอบหลักที่ส าคัญ 4 องค์ประกอบ ได้แก่ 1) เป้าหมายและ หลักการ 2) หลักสูตรและสื่อการสอน 3) เทคนิคและวิธีการสอน และ 4) การพัฒนาผู้สอนและผู้เรียน ค าส าคัญ: แนวทาง, การบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีน, โรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) Abstract This study aimed to develop a guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. The study was divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 was to investigate the present state and needs on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration from the perspectives of the involved personnel in Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Phase 2 was to create guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and to verify the accuracy and suitability of the guidelines by interviewing experts on teaching Chinese language and school management. A questionnaire, a semi-structured interview form, and an evaluation form were used as tools for collecting data. Percentage, mean, and Standard Deviation were employed for analyzing quantitative data. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) and content analysis were used for needs assessment and analyzing qualitative data, respectively. The results of this research found that the actual state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in all aspects was at a high level ( x =4.00) and the expected state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in the overall was at the highest level ( x =4.62). The difference between the actual state and the expected state were significant different at .01 level. -

Spice Large.Pdf

Gernot Katzer’s Spice List (http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com/engl/) 1/70 (November 2015) Important notice Copyright issues This document is a byproduct of my WWW spice pages. It lists names of spices in about 100 different languages as well as the sci- This document, whether printed or in machine-readable form, may entific names used by botanists and pharmacists, and gives for each be copied and distributed without charge, provided the above no- local name the language where it is taken from and the botanical tice and my address are retained. If the file content (not the layout) name. This index does not tell you whether the plant in question is is modified, this should be indicated in the header. discussed extensively or is just treated as a side-note in the context of another spice article. Employees of Microsoft Corporation are excluded from the Another point to make perfectly clear is that although I give my above paragraph. On all employees of Microsoft Corporation, a best to present only reliable information here, I can take no warrant licence charge of US$ 50 per copy for copying or distributing this of any kind that this file, or the list as printed, or my whole WEB file in all possible forms is levied. Failure to pay this licence charge pages or anything else of my spice collection are correct, harm- is liable to juristical prosecution; please contact me personally for less, acceptable for non-adults or suitable for any specific purpose. details and mode of paying. All other usage restrictions and dis- Remember: Anything free comes without guarantee! claimers decribed here apply unchanged. -

The Last of the Thai Traditional Music Teachers

Uncle Samruay — the Last of the Thai Traditional Music Teachers The SPAFA crew visited the Premjai House of Music to explore its hospital-based concept of a school/repair centre, where Patsri Tippayaprapai interviewed the 69-year-old renowned master musician Samruay Premjai. The people of Thailand have been making indigenous musical instruments since ancient times, during which they also adapted instruments of other countries to create what are now regarded as Thai musical instruments. Through contact with Indian culture, the early Thai kingdoms assimilated and incorporated Indian musical traditions in their musical practices, using instruments such as the phin, sang, pi chanai, krachap pi, chakhe, and thon, which were referred to in the Master Samruay Premjai Tribhumikatha, an ancient book in the Thai language; they were also mentioned on a stone inscription (dated to the time of King Ramkhamhaeng, Sukhothai period). During the Ayutthaya period, the Thai instrumental ensemble consisted of between four and eight musicians, when songs known as 'Phleng Rua' were long and performed with refined skills. The instrumental ensemble later expanded to a composition of twelve musicians, and music became an indispensable part of theatre and other diverse occasions such as marriages, funerals, festivals, etc.. There Illustration ofSukhotai period ensemble of musicians are today approximately fifty kinds of Thai musical instruments, including xylophones, chimes, flutes, gongs, stringed instruments, and others. SPAFA Journal Vol. 16 No. 3 19 Traditionally, Thai musicians were trained by their teachers through constant practising before their trainers. Memory, diligence and perseverance were essential in mastering the art. Today, however, that tradition is gradually being phased out. -

Affirmation of Shan Identities Through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend 'Khun Sam Law'

Thammasat Review 2015, 18(1): 1-26 Affirmation of Shan Identities through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend ‘Khun Sam Law’ Khamindra Phorn Department of Anthropology & Sociology Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University [email protected] Abstract Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim is an 18th-century legend popular among people in all walks of life in Myanmar’s Shan State. To this day, the story is narrated in novels, cartoons, films and songs. If Romeo and Juliet is a classical romance of 16th-century English literature, then Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, penned by Nang Kham Ku, is the Shan equivalent of William Shakespeare’s masterpiece. Based on this legend, Sai Jerng Harn, a former pop-star, and Sao Hsintham, a Buddhist monk, recast and reimagined the legendary figure as a Shan movement on the one hand, and migrant Shans in Chiang Mai as a Shan Valentine’s celebration and protector of Khun Sam Law lineage on the other. These two movements independently appeared within the Shans communities. This paper seeks to understand how this Shan legend provides a basic source for Shan communities to reimagine and to affirm their identities through the reincarnation and lineage. The pop-star claims to be a reincarnation of Khun Sam Law, while the migrant Shans in Chiang Mai, who principally hail from Kengtawng, claim its lineage continuity. Keywords: Khun Sam Law legend, Khun Sam Law Family, Khun Sam Law movement, Sai Jerng Harn, Sao Hsintham, Kengtawng Thammasat Review 1 Introduction According to Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, a popular folktale originating in Myanmar’s Shan State, Khun Sam Law was a young merchant from Kengtawng, a small princedom under Mongnai city-state. -

The State Funeral of HRH Princess Galyani Vadhana Kroma Luang Naradhiwas Rajanagarindra

The State Funeral of HRH Princess Galyani Vadhana Kroma Luang Naradhiwas Rajanagarindra 2 January 2008 Her Royal Highness the Princess Galyani Vadhana, Princess of Naradhiwas was admitted into the Siriraj Hospital in June 2007 for cancer treatment. While she was at the hospital, she still attended functions once in a while, until October when the Royal Household Bureau first announced an update on the Princess' health on 25 October 2007. Since then her health had deteriorated, and the public became worried. The bad news came on the morning of 2 January 2008, when the Thai people tuned on their TVs and radios to hear the morning news and found out that the Princess had passed away at 2.54am that day. Although many had sort of expected this bad news since her health was at a point where the doctors could not do anything anymore, it was still a shock that the beloved Princess has finally departed the world. The picture of His Majesty leaving the hospital after his sister has died, which was printed in all the newspapers the next day, prety much summed up how he felt, as well as how the Thai people felt. His Majesty has accorded the highest honour for his only sister, and arranged for her bathing rites to take place at the Piman Rataya Throne Hall, follow by the lying in state at the Dusit Maha Prasart Throne Hall in the Grand Palace, the same practice as past Kings and senior members of the Royal Family, which included HM Queen Sri Bajarindra, King Rama VIII, and more recently HM Queen Rambai Barni in 1984 and HRH the Princess Sri Nagarindra, the Princess Mother in 1995. -

CUHK Papers in Linguistics,Number 1. INSTITUTION Chinese Univ

DOCUMENT AESUME ED 364 067 FL 021 534 AUTHOR Ching, Teresa, Ed. TITLE CUHK Papers in Linguistics,Number 1. INSTITUTION Chinese Univ. of Hong Kong.Linguistics Research Lab. SPONS AGENCY Lingnan Univ. (China).; UnitedBoard of Higher Christian Education in Asia. REPORT NO ISSN-1015-1672 PUB DATE Aug 89 NOTE 118p.; For individualpapers, see FL 021 535-539. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT CUHK Papers in Linguistics; nlAug 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *English (Second Language);*Evaluation Methods; *Grammar; *HeariagImpairments; Language Acquisition; Mandarin Chinese;*Second Language Learning; *Standard SpokenUsage; Syntax IDENTIIIERS *Linear Ordering;Quantifiers ABSTRACT Papers included in thisvolume include the following: "Prosodic Aspects of Hearing-Impaired Children: AQualitative and Quantitative Assessmer' (Teresa Y. C. Ching); "TheRole of Linear Order in the Acquisit: of Quantifier Scope in Chinese"(ThoLas H. T. Lee); "Some Neglected Syntactic Phenomena inNear-standard English" (Mark Newbrook); "The Effect of ExplicitInstruction on the Acquisition of English Grammatical Structures by ChineseLearners" (Yan-ping Zhou); and "An Essay on Toffee Apple andTreacle Tart, Being an Imitation ofCockney Punning for TOEFL W. Ho). (Author/VWL) and TEASL" (Louise S. *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied byEDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** CUBIC