UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE of BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320)

1 [The following essay was published in the Jewish Studies Quarterly 5 (1998) 318-28. The essay appears here substantially as published but with some additions indicated in this color .]. RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE OF BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320) David M. Goldenberg While the biblical corpus contains references to the people and practices of black Africa (e.g. Isa 18:1-2), little such information is found in the rabbinic corpus. To a degree this may be due to the different genre of literature represented by the rabbinic texts. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that black Africa and its peoples would be entirely unknown to the Palestinian Rabbis of the early centuries. An indication of such knowledge is, I believe, found imbedded in a midrashic text of the third century. Deut 32:21 describes the punishment God has decided to inflict on Israel for her disloyalty to him: “I will incense them with a no-folk ( be-lo < >am ); I will vex them with a nation of fools ( be-goy nabal ).” A tannaitic commentary to the verse states: ואני אקניאם בלא עם : אל תהי קורא בלא עם אלא בלוי עם אלו הבאים מתוך האומות ומלכיות ומוציאים אותם מתוך בתיהם דבר אחר אלו הבאים מברבריא וממרטניא ומהלכים ערומים בשוק “And I will incense them with a be-lo < >am .” Do not read bl < >m, but blwy >m, this refers to those who come from among the nations and kingdoms and expel them [the Jews] from their homes. Another interpretation: This refers to those who come from barbaria and mr ãny <, who go about naked in the market place. -

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the Book of the Dead, two of these deities were charged with ending a storm at the city of Pe, and the next chapter assigns the other two of these deities to the city of Nekhen. The Pyramid Texts describe these gods as bearing Osiris's body to the heavens and, in the Middle Kingdom, the names of these deities were placed on the corner pillars of coffins. Maarten Raven has argued that the association of these gods with the intestines developed later from their original function, as gods of the four quarters of the world. Isis was both their mother and grandmother. For 10 points, consisting of Qebehsenuef, Imsety, Duamutef, and Hapi, the protectors of the organs stored in the canopic jars which bear their heads, these are what group of deities, the progeny of a certain falconheaded god? ANSWER: Sons of Horus [or Children of Horus; accept logical equivalents] 2. According to Plutarch, the proSpartan Kimon sent a delegation with a secret mission to this deity, though he died before its completion, prompting the priest to inform his men that Kimon was already with this deity. Pausanias says that Pindar offered a statue of this god carved by Kalamis in Thebes and Pythian IV includes Medea's prediction that "the daughter of Epaphus will one day be planted... amid the foundations" of this god in Libya. Every ten days a cult statue of this god was transported to Medinet Habu in western Thebes, where he had first created the world by fertilizing the world egg. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

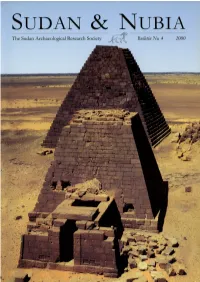

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

I Introduction: History and Texts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Excerpt More information I Introduction: History and Texts A. Historical Setting The Kingdom of Meroe straddled the Nile in what is now known as Nubia from as far north as Aswan in Egypt to the present–day location of Khartoum in Sudan (see Map 1). Its principal language, Meroitic, was not just spoken but, from the third century BC until the fourth century AD, written as well. The kings and queens of this kingdom once proclaimed themselves pha- raohs of Higher and Lower Egypt and, from the end of the third millennium BC, became the last rulers in antiquity to reign on Sudanese soil. Centuries earlier the Egyptian monarchs of the Middle Kingdom had already encountered a new political entity south of the second cataract and called it “Kush.” They mentioned the region and the names of its rulers in Egyptian texts. Although the precise location of Kush is not clear from the earliest attestations, the term itself quickly became associated with the first great state in black Africa, the Kingdom of Kerma, which developed between 2450 and 1500 BC around the third cataract. The Egyptian expansion by the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) colonized this area, an occupation that lasted for more than five centuries, during which the Kushites lost their independence but gained contact with a civilization that would have a last- ing influence on their culture. During the first millennium BC, in the region of the fourth cataract and around the city of Napata, a new state developed that slowly took over the Egyptian administration, which was withdrawing in this age of decline. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

WG2 M52 Minutes

ISO.IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting Minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland 2009-04-20/24 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran, Recording Secretary, and Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the Due Date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2009-10-12 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 60 (including cover sheet) Michael Y. Ksar Convener – ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 22680 Alcalde Rd Phone: +1 408 255-1217 Cupertino, CA 95014 Email: [email protected] U.S.A. ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland; 2009-04-20/24 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Mike Ksar ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 3573 2nd Call Meeting # 54 in Dublin; Mike Ksar; 2009-02-16 Mr. -

The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea

Price 50p INSCRIPTIONS The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea Whatever else you do this Issue 28 Christmas… December 2008 In this issue: Re-discovery of the Re-discovery of the South Asasif Necropolis 1 South Asasif Necropolis Fakes Case in the Egypt Centre 2 by Carolyn Graves-Brown ELENA PISCHIKOVA is the Director of the South Introducing Ashleigh 2 Asasif Conservation Project and a Research by Ashleigh Taylor Scholar at the American University in Cairo. On Editorial 3 7 January 2009, she will visit Swansea to speak Introducing Kenneth Griffin 3 on three decorated Late Period tombs that were by Kenneth Griffin recently rediscovered by her team on the West A visit to Highclere Castle 4 Bank at Thebes. by Sheila Nowell Life After Death on the Nile: A Described by travellers of the 19th century as Journey of the Rekhyt to Aswan 5 among the most beautiful of Theban tombs, by L. S. J. Howells these tombs were gradually falling into a state X-raying the Animal Mummies at of destruction. Even in their ruined condition the Egypt Centre: Part One 7 by Kenneth Griffin they have proved capable of offering incredible Objects in the Egypt Centre: surprises. An entire intact wall with an Pottery cones 8 exquisitely carved offering scene in the tomb of by Carolyn Graves-Brown Karakhamun, and the beautifully painted ceiling of the tomb of Irtieru are among them. This promises to be a fascinating talk from a very distinguished speaker. Please do your best to attend and let’s give Dr Pischikova a decent audience! Wednesday 7 January 7 p.m. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Selima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Grids and Datumsâšrepublic of Sudan

REPUBLIC OF rchaeological excavation of sites on the Nile above Aswan has confirmed human “Ahabitation in the river valley during the Paleolithic period that spanned more than 60,000 years of Sudanese history. By the eighth millennium B.C., people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mud-brick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding. Contact with Egypt probably occurred at a formative stage in the culture’s development because of the steady movement of population along the Nile River. Skeletal remains suggest a blending of negroid and Mediterranean populations during the Neolithic period (eighth to third millenia B.C.) that has remained relatively stable until theDelivered present, by Ingenta despite gradual infiltrationIP: 192.168.39.211by other elements. On: Sat, 25 Sep 2021 12:42:54 Copyright: American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Northern Sudan’s earliest historical record comes from Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream from the first cataract, called Cush, as “wretched.” For more than 2,000 years after the Old kingdom emerged at Karmah, near present-day Dunqulah. After Egyptian power revived during the New Kingdom (ca. Kingdom (ca. 2700-2180 B.C.), Egyptian political 1570-1100 B.C.), the pharaoh Ahmose I incorporated Cush and economic activities determined the course as an Egyptian province governed by a viceroy. Although of the central Nile region’s history. Even during Egypt’s administrative control of Cush extended only down to intermediate periods when Egyptian political power the fourth cataract, Egyptian sources list tributary districts in Cush waned, Egypt exerted a profound cultural reaching to the Red Sea and upstream to the confluence of the and religious influence on the Cushite people. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).