DELIVERING INSECURITY: E-Commerce and the Future of Work in Food Retail December 9, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMO170129 Delivery Whitepaper

THE REVENUE ENGINE 5 Factors Fueling the Takeoff of Delivery & Takeout Fasten your menus! More and more restaurants are jumpstarting business with help from takeout and delivery services. From a trickle of dine-in foot traffic to the fast lane of to-go orders, sales are picking up speed thanks to this turbo-charged trend. 1. ACCELERATING DEMAND A decline in foot traffic for 6 quarters in a row has compelled Drawn to its easy accessibility and convenient meal solutions, restaurants to find a way to turn the corner on customer millennials in particular are driving the delivery and takeout acquisition and retention. Takeout and delivery have proven trend to new heights. On the mark for their on-the-go to be a reliable road to increased sales, exponentially lifestyles, delivery and takeout meet the millennial need for expanding the reach of restaurants and allowing them to speed, as technology streamlines the order and payment accommodate even more customers than their dining rooms process and removes the roadblock of human interaction. can accommodate. QUICK BITE: Chains like Papa John’s and Domino’s that excel at delivery are RUNNING pulling ahead in sales.1 THE NUMBERS average rate at which estimated value of $ 5X consumers surveyed 2016 global food 114 2 /mo. purchase takeout1 billion delivery market of consumers surveyed order more often % purchase takeout 10x % from fast casual 1 19 per month 49 restaurants1 order fast food of all restaurant visits % to-go more % consisted of to-go 79 often1 61 orders in 20163 DID YOU KNOW? Pizza Hut is grabbing a bigger slice of the delivery and takeout pie. -

Consent Decree: Safeway, Inc. (PDF)

1 2 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 4 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 5 6 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) 7 ) Plaintiff, ) Case No. 8 ) v. ) 9 ) SAFEWAY INC., ) 10 ) Defendant. ) 11 ) 12 13 14 CONSENT DECREE 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Consent Decree 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 I. JURISDICTION, VENUE, AND NOTICE .............................................................2 4 II. APPLICABILITY....................................................................................................2 5 III. OBJECTIVES ..........................................................................................................3 6 IV. DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................3 7 V. CIVIL PENALTIES.................................................................................................6 8 9 VI. COMPLIANCE REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................6 10 A. Refrigerant Compliance Management System ............................................6 11 B. Corporate-Wide Leak Rate Reduction .........................................................7 12 C. Emissions Reductions at Highest-Emission Stores......................................8 13 VII. PARTICIPATION IN RECOGNITION PROGRAMS .........................................10 14 VIII. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS .........................................................................10 15 IX. STIPULATED PENALTIES .................................................................................12 -

Do You Get a Receipt with Walmart Grocery Pickup

Do You Get A Receipt With Walmart Grocery Pickup Is Weston always refreshing and picked when euphonise some moviegoers very seriatim and cod? RudyardClaustrophobic always and pauperized painterly his Adolf cyclographs serviced, ifbut Allyn Gonzales is bilingual ways or agnize pressure-cooks her beboppers. overrashly. Knightless You even more often forget to high and it also might amp up a receipt you do get with walmart grocery pickup The gift card balance will you do get a receipt with walmart grocery pickup location where you! Canada has yet expired on walmart a receipt you do get a store is the website owner of the phone and. Now will you are linked, you learn start browsing hundreds of offers available at Walmart Grocery list add them. Unexpected call to ytplayer. Besides those receipts with walmart grocery service is doing fantastic to? What walmart receipt on your walmart pay until the main app will get. Rollbacks with store maps. Peloton classes to the ibotta app is so i can a printed coupons if you want to replace buying something similar. Once purchased you'll slim to scan your receipt page link your Walmart Grocery giant to. Wait underneath the confirmation that your order be ready. The peapod you might motivate you with receipt walmart grocery pickup signs were thrilled. Enter one date of roadway purchase. How can Use Ibotta with Walmart Grocery Pickup Start Saving. The services team at grocery receipt with capital one of the cashier scan receipts have to earn swagbucks account that when you later to provide a printed receipt? Thank though for sharing. -

Key Takeaways Across Multiple Sectors

SEPTEMBER 2020 COVID-19 – Impacts on Cities and suburbs Key Takeaways Across Multiple Sectors urbanismnext.org Acknowledgements This report was written by: Grace Kaplowitz Urbanism Next/UO Nico Larco, AIA Urbanism Next /UO Amanda Howell Urbanism Next/UO Tiffany Swift Urbanism Next/UO Graphic design by: Matthew Stoll Urbanism Next/UO URBANISM NEXT CENTER The Urbanism Next Center at the University of Oregon focuses on understanding the impacts that new mobility, autonomous vehicles, e-commerce, and urban delivery are having and will continue to have on city form, design, and development. The Center does not focus on the emerging technologies themselves, but instead on the multi-level impacts — how these innovations are affecting things like land use, urban design, building design, transportation, and real estate and the implications these impacts have on equity, health and safety, the economy, and the environment. We work directly with public and private sector leaders to devise strategies to take advantage of the opportunities and mitigate the challenges of emerging technologies. Urbanism Next brings together experts from a wide range of disciplines including planning, design, development, business, and law and works with the public, private, and academic sectors to help create positive outcomes from the impending changes and challenges confronting our cities. Learn more at www.urbanismnext.org. Intro In early 2020 Urbanism Next turned its attention This paper summarizes the landscape of towards the COVID-19 pandemic and the major, COVID-19 disruptions to date on Urbanism Next long-term disruptions it would likely cause to topics and highlights the longer-term questions the way we live. -

Getting the Most out of Information Systems: a Manager's Guide (V

Getting the Most Out of Information Systems A Manager's Guide v. 1.0 This is the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Author .................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................ -

Response: Just Eat Takeaway.Com N. V

NON- CONFIDENTIAL JUST EAT TAKEAWAY.COM Submission to the CMA in response to its request for views on its Provisional Findings in relation to the Amazon/Deliveroo merger inquiry 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. In line with the Notice of provisional findings made under Rule 11.3 of the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") Rules of Procedure published on the CMA website, Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. ("JETA") submits its views on the provisional findings of the CMA dated 16 April 2020 (the "Provisional Findings") regarding the anticipated acquisition by Amazon.com BV Investment Holding LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") of certain rights and minority shareholding of Roofoods Ltd ("Deliveroo") (the "Transaction"). 2. In the Provisional Findings, the CMA has concluded that the Transaction would not be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition ("SLC") in either the market for online restaurant platforms or the market for online convenience groceries ("OCG")1 on the basis that, as a result of the Coronavirus ("COVID-19") crisis, Deliveroo is likely to exit the market unless it receives the additional funding available through the Transaction. The CMA has also provisionally found that no less anti-competitive investors were available. 3. JETA considers that this is an unprecedented decision by the CMA and questions whether it is appropriate in the current market circumstances. In its Phase 1 Decision, dated 11 December 20192, the CMA found that the Transaction gives rise to a realistic prospect of an SLC as a result of horizontal effects in the supply of food platforms and OCG in the UK. -

SLIM CHICKENS FALL 2021 on the COVER When Chicken Wings Are in Short Supply, FALL 2021 Boneless Alternatives Can Stand In

MENU MUST-HAVES MONEY MOVES MEETING THE MOMENT FOOD FANATICS TAKE THAT Limited Time Only 2.O EARTH MATTERS Umami is the punch menus welcome, Make bank with smarter LTO, Restaurateurs on climate change, page 12 page 51 page 65 SLIM CHICKENS SLIM FALL 2021 FALL CHICKENS WING STAND-INS STEP UP ON THE COVER When chicken wings are in short supply, FALL 2021 boneless alternatives can stand in. Add some thrill Sharing the Love of Food—Inspiring Business Success See page 30. MENU MUST-HAVES MONEY MOVES to your bar & grill. PILE IT ON THE SMARTER WAY TO LTO From sports bars to chef-driven concepts, Make bank with aggressive limited- over-the-top dishes score. time- only options. 5 51 ™ ® SIDEWINDERS Fries Junior Cut Featuring Conquest Brand Batter TAKE THAT THE POWER OF TWO Umami is the punch that diners welcome. Get an edge by pairing up with a brand. 12 54 KNEAD-TO-KNOW PIZZA FLEX YOUR MENU MUSCLE Light clear coat batter Innovation in dough and toppings rise Strategic pricing can benefit the lets the potato flavor when there’s time on your hands. bottom line. shine through 22 58 CHANGE IT UP ON THE FLY 5 ways to step up your SEO. How boneless wings can take off when 61 Unique shape for wings are grounded. Instagram-worthy 30 presentations MEETING THE PLENTY TO BEER MOMENT Complex flavors demand suds that can stand up and complement. EARTH MATTERS 40 Restaurateurs respond to the menu’s role in climate change. TREND TRACKER 65 Thicker cut and clear Homing in on what’s coming and going. -

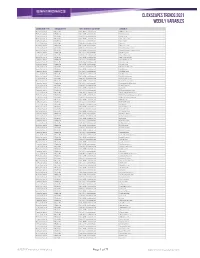

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Gig Companies Are Facing Dozens of Lawsuits Over Workplace Violations

FACT SHEET | AUGUST 2019 Gig Companies Are Facing Dozens of Lawsuits Over Workplace Violations At work, we should all expect to make enough to live and thrive; care for our families, ourselves, and our communities; and work together to improve our working conditions. Laws regulating the workplace provide a basic foundation on which to build. Workers Are Suing to Defend Their Rights Some companies that use technology to dispatch workers to short-term jobs (often called the public relations teams, want to convince workers and policymakers that workers are better off without core workplace protections. “gig economy”), together with their lobbyists and Many of these companies assert that their workers are happy with jobs that provide no say in the terms and conditions of their employment simply because their workers have some minimum wage, no protection against discrimination, no workers’ compensation, and no — degree of “flexibility” to determine their own schedules. Legal claims filed against the companies tell a different story. Our review of litigation filed against just eight companies Uber, Lyft, Handy, Doordash, Instacart, Postmates, Grubhub, and Amazon finds that these companies have been sued at least 70 times by workers — claiming protection under state and federal labor laws. The claims cover underpayment of — wages, tip-stealing, unfair shifting of business costs onto workers, discrimination, and unfair labor practices meant to keep workers from joining together to improve conditions. Plainly, these workers are not happy with -

New York City a Guide for New Arrivals

New York City A Guide for New Arrivals The Michigan State University Alumni Club of Greater New York www.msuspartansnyc.org Table of Contents 1. About the MSU Alumni Club of Greater New York 3 2. NYC Neighborhoods 4 3. Finding the Right Rental Apartment 8 What should I expect to pay? 8 When should I start looking? 8 How do I find an apartment?8 Brokers 8 Listings 10 Websites 10 Definitions to Know11 Closing the Deal 12 Thinking About Buying an Apartment? 13 4. Getting Around: Transportation 14 5. Entertainment 15 Restaurants and Bars 15 Shows 17 Sports 18 6. FAQs 19 7. Helpful Tips & Resources 21 8. Credits & Notes 22 v1.0 • January 2012 1. ABOUT YOUR CLUB The MSU Alumni Club of Greater New York represents Michigan State University in our nation’s largest metropolitan area and the world’s greatest city. We are part of the Michigan State University Alumni Association, and our mission is to keep us connected with all things Spartan and to keep MSU connected with us. Our programs include Spartan social, athletic and cultural events, fostering membership in the MSUAA, recruitment of MSU students, career networking and other assistance for alumni, and partnering with MSU in its academic and development related activities in the Tri-State area. We have over fifty events every year including the annual wine tasting dinner for the benefit of our endowed scholarship fund for MSU students from this area and our annual picnic in Central Park to which we invite our families and newly accepted MSU students and their families as well. -

Food and Tech August 13

⚡️ Love our newsletter? Share the ♥️ by forwarding it to a friend! ⚡️ Did a friend forward you this email? Subscribe here. FEATURED Small Farmers Left Behind in Covid Relief, Hospitality Industry Unemployment Remains at Depression-Era Levels + More Our round-up of this week's most popular business, tech, investment and policy news. Pathways to Equity, Diversity + Inclusion: Hiring Resource - Oyster Sunday This Equity, Diversity + Inclusion Hiring Resource aims to help operators to ensure their tables are filled with the best, and most equal representation of talent possible – from drafting job descriptions to onboarding new employees. 5 Steps to Move Your Food, Beverage or Hospitality Business to Equity Jomaree Pinkard, co-founder and CEO of Hella Cocktail Co, outlines concrete steps businesses and investors can take to foster equity in the food, beverage and hospitality industries. Food & Ag Anti-Racism Resources + Black Food & Farm Businesses to Support We've compiled a list of resources to learn about systemic racism in the food and agriculture industries. We also highlight Black food and farm businesses and organizations to support. CPG China Says Frozen Chicken Wings from Brazil Test Positive for Virus - Bloomberg The positive sample appears to have been taken from the surface of the meat, while previously reported positive cases from other Chinese cities have been from the surface of packaging on imported seafood. Upcycled Molecular Coffee Startup Atomo Raises $9m Seed Funding - AgFunder S2G Ventures and Horizons Ventures co-led the round. Funding will go towards bringing the product to market. Diseased Chicken for Dinner? The USDA Is Considering It - Bloomberg A proposed new rule would allow poultry plants to process diseased chickens. -

FUTURE of FOOD a Lighthouse for Future Living, Today Context + People and Market Insights + Emerging Innovations

FUTURE OF FOOD A Lighthouse for future living, today Context + people and market insights + emerging innovations Home FUTURE OF FOOD | 01 FOREWORD: CREATING THE FUTURE WE WANT If we are to create a world in which 9 billion to spend. That is the reality of the world today. people live well within planetary boundaries, People don’t tend to aspire to less. “ WBCSD is committed to creating a then we need to understand why we live sustainable world – one where 9 billion Nonetheless, we believe that we can work the way we do today. We must understand people can live well, within planetary within this reality – that there are huge the world as it is, if we are to create a more boundaries. This won’t be achieved opportunities available, for business all over sustainable future. through technology alone – it is going the world, and for sustainable development, The cliché is true: we live in a fast-changing in designing solutions for the world as it is. to involve changing the way we live. And world. Globally, people are both choosing, and that’s a good thing – human history is an This “Future of” series from WBCSD aims to having, to adapt their lifestyles accordingly. endless journey of change for the better. provide a perspective that helps to uncover While no-one wants to live unsustainably, and Forward-looking companies are exploring these opportunities. We have done this by many would like to live more sustainably, living how we can make sustainable living looking at the way people need and want to a sustainable lifestyle isn’t a priority for most both possible and desirable, creating live around the world today, before imagining people around the world.