Downloads/Pdf/World Class Streets Gehl 08.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graduationl Speakers

Graduationl speakers ~~~~~~~~*L-- --- I - I -· P 8-·1111~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ stress public service By Andrew L. Fish san P. Thomas, MIT's Lutheran MIT President Paul E. Gray chaplain, who delivered the inlvo- '54 told graduating students that cation. "Grant that we may use their education is "more than a the privilege of this MIT educa- meal ticket" and should be used tion and degree wisely - not as to serve "the public interest and an entitlement to power or re- the common good." His remarks gard, but as a means to serve," were made at MIT's 122nd com- Thomas said. "May the technol- mencement on May 27. A total ogy that we use and develop be of 1733 students received 1899 humane, and the world we create degrees at the ceremony, which with it one in which people can was held in Killian Court under live more fully human lives rather sunny skies, than less, a world where clean air The importance of public ser- and water, adequate food and vice was also emphasized by Su- shelter, and freedom from fear and want are commonplace rath- Prof. IVMurman er than exceptional." named to Proj. Text of CGray's commencement address. Page 2. Athena post In his commencement address, By Irene Kuo baseball's National League Presi- Professor Earll Murman of the dent A. Bartlett Giamatti urged Department of Aeronautics and graduates to "have the courage to Astronautics was recently named connect" with people of all ideo- the new director of Project Athe- logies. Equality will come only ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~,,4. na by Gerald L. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

Mitchell-W-City-Of-Bits.Pdf

[ Welcome | Agora | Table of Contents | Surf Sites | Ordering Information ] [ Copyright Information | 1. Pulling Glass | 2. Electronic Agoras | 3. Cyborg Citizens | 4. Recombinant Architecture | 5. Soft Cities | 6. Bit Biz | 7. Getting to the Good Bits | Surf Sites | Acknowledgements ] Title page image/animation: MPEG (900K), Quicktime (4.1M), or GIF (59K) image. City of Bits WWW Team © 1995-1997 MIT City of Bits Space, Place, and the Infobahn by William J. Mitchell First MIT Press paperback edition, 1996 © Copyright 1995-1997 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, with the sole exception of use at this site. The book was set in Bembo and Meta by Wellington Graphics and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Mitchell, William J. City of bits : space, place, and the infobahn / William J. Mitchell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-13309-1 (HB), 0-262-63176-8 (PB) 1. Computer networks. 2. Information technology. 3. Virtual reality I. Title TK5105.5.M57 1995 95-7212 303.48'33--dc20 CIP [ Comments | Search | Choice Sites | Main Entrance | Contents | Surf Sites | Ordering Info ] City of Bits WWW Team © 1995-1997 MIT As the fin-de-K countdown cranked into the nineties, I became increasingly curious about the technicians I saw poking about in manholes. They were not sewer or gas workers; evidently they were up to something quite different. -

NR Science Cities ENG

“Science Cities” : Science Campuses and Clusters in 21st Century Metropolises > Keynote IAU-île de France 1 March 2010 “Science Cities” : Science Campuses and Clusters in 21st Century Metropolises > Keynote A study examining a pressing issue in Paris Ile-de-France Creating science campuses that draw on an landscape of graduate studies in Ile-de exchange of knowledge generated by France. They not only differ in terms of the different disciplines is a major focus for all scientific disciplines they house and the cities seeking to attract innovative and extent of the building projects, but also creative R&D activities to their regions. These regarding each specific territorial context. places are widely viewed as essential Issues relating to urban integration and the resources for the development of high-tech construction timeframe for these two business clusters, which are pathways to campuses will therefore, by definition, be value creation and highly qualified jobs. Yet very different, especially as the surface this is not always the case, as demonstrated areas, capacity and access via public by the mixed results in terms of start-up and transportation are not comparable. jobs creations at the large Adlershof project in Berlin, or the problematic gestation Condorcet will concentrate on the social experienced by the Saclay technopole sciences and will occupy 180,000 sq.m of development for twenty years. floor space and approximately 7.5 hectares (18.4 acres) on either side of the Boulevard The selectioni of the Saclay and Condorcet Périphérique, to the northern edge of the city projects for the “Opération Campus”, a vast of Paris. -

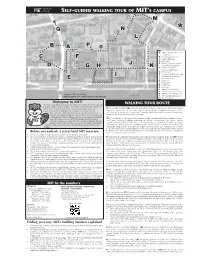

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street. -

Learning Spaces Diana Oblinger EDUCAUSE

The College at Brockport: State University of New York Digital Commons @Brockport Brockport Bookshelf 2006 Learning Spaces Diana Oblinger EDUCAUSE Joan K. Lippincott The College at Brockport, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf Part of the Databases and Information Systems Commons, and the Interior Architecture Commons Repository Citation Oblinger, Diana and Lippincott, Joan K., "Learning Spaces" (2006). Brockport Bookshelf. 78. http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf/78 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @Brockport. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brockport Bookshelf by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @Brockport. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning Spaces Diana G. Oblinger, Editor Learning Spaces Diana G. Oblinger, Editor ISBN 0-9672853-7-2 ©2006 EDUCAUSE. Available electronically at www.educause.edu/learningspaces Learning Spaces Part 1: Principles and Practices Chapter 1: Space as a Change Agent Diana G. Oblinger • Acknowledgments • Endnote • About the Author Chapter 2: Challenging Traditional Assumptions and Rethinking Learning Spaces Nancy Van Note Chism • Changing Our Assumptions • Intentionally Created Spaces • Opportunities and Barriers • Moving Forward • Hope for the Future • Endnotes • About the Author Chapter 3: Seriously Cool Places: The Future of Learning-Centered Built Environments William Dittoe • Marcy • The Learner-Centered Difference • Endnotes • About the Author Chapter 4: Community: The Hidden Context for Learning Deborah J. Bickford and David J. Wright • Why Community? • Community as a Context for Learning • Conclusion • Endnotes • About the Authors Chapter 5: Student Practices and Their Impact on Learning Spaces Cyprien Lomas and Diana G. -

The Innovation Institute: from Creative Inquiry Through Real-World Impact at MIT

The Innovation Institute: From Creative Inquiry Through Real-World Impact at MIT by Joost Paul Bonsen S.B. Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, MIT, 1990 Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of ARCHIVES Master of Science in the Management of Technology MASAHSET ISIIf MASSACHUS•ETS INSTIT•f at the OF TECHNOLOGY Massachusetts Institute of Technology AUG 3 1 2006 June 2006 LIBRARIES © 2006 Joost Paul Bonsen. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: - I- --I I - / IVfl~T~loaVSchool of Management T gSloaSchool of Management May 12, 2006 Certified by: Alex (Sandy) Pentland Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor /F"/ , I /--, Accepted by: SStephen Sacca Director, MIT Sloan Fellows Program in Innovation and Global Leadership The Innovation Institute: From Creative Inquiry Through Real-World Impact at MIT by Joost Paul Bonsen Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Management of Technology Abstract This document is an exploration into the past, present, and emerging future of MIT from the perspective of a participant-in and observer-of Institute life and learning, and seeks to better understand how creative inquiry at the Institute leads to real-world impact. We explore the Institute's history, mission, and creative ethos. We survey MIT's links to industry, highlight the inner-connections between the triad of research, education and extracurriculars, and explore the rich entrepreneurial ecosystem, how the Institute formally and informally educates and inspires new generations of founders, builders, and leaders. -

EAST CAMPUS / MIT GATEWAY Alternative Approaches

EAST CAMPUS / MIT GATEWAY Alternative Approaches Prepared by The Design Committee July 19. 2013 EAST CAMPUS / MIT GATEWAY Alternative Approaches This report lays out strategic options for design and program of the MIT East Campus and a new Gateway to the institute in the Kendall Square area. Its purpose is to define principles for the planning and design of this critical area of the campus, in light of the recent up-zoning approval given to MIT by the City of Cambridge, and the intention of the MIT Investment Management Company (MITIMCO) to construct approximately 900,000 sq ft of commercial office and laboratory space on the campus south of Main Street. The report examines alternative approaches to achieving this amount of development that will also result in a high quality campus environment, mesh with the broader public realm of Kendall Square and the Charles River, and serve student and future academic needs. This brief report and design study was prepared by a Design Committee of architecture, urban design, and planning faculty in the School of Architecture and Planning. The Design Committee was appointed by Provost Chris Kaiser and Executive Vice President and Treasurer Israel Ruiz following a recommendation of the faculty Task Force on Commu- nity Engagement in 2030 Planning on Development of MIT- Owned Property in Kendall Square. The Task Force was charged by the provost in 2012 with reviewing the Kendall Square project, and recommending whether to go forward. In the process, the Task Force raised concerns about the conceptual diagram put forth for development of the area, which had been prepared by MITIMCO. -

Geometric, Topological & Semantic Analysis of Multi-Building Floor

Geometric, Topological & Semantic Analysis of Multi-Building Floor Plan Data by Emily J. Whiting B.A.Sc. Engineering Science University of Toronto, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2006 © 2006 Emily J. Whiting. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Department of Architecture May 25, 2006 Certified by: Seth Teller Associate Professor of Computer Science & Engineering Thesis Supervisor Certified by: Takehiko Nagakura Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Co-Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Professor of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 2 Geometric, topological & semantic analysis of multi-building floor plan data Axel Kilian Post-Doctoral Associate in Computation, Department of Architecture Thesis Reader 3 Geometric, topological & semantic analysis of multi-building floor plan data Geometric, Topological & Semantic Analysis of Multi-Building Floor Plan Data by Emily J. Whiting Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 25, 2006 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies. ABSTRACT Generating a comprehensive model of a university campus or other large urban space is a challenging undertaking due to the size, geometric complexity, and levels of rich semantic information contained in inhabited environments. This thesis presents a practical approach to constructing topological models of large environments from labeled floor plan geometry. -

The MIT EECS Connector

SPRING 2013 Annual News from the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science the MIT EECS Connector 1 4 2 5 3 6 7 Annual News from the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Perspectives from the the MIT EECS Connector Department Head Anantha P. Chandrakasan Perspectives from the Department Head : 1 Department Head Department Snapshot : 3 Munther A. Dahleh SuperUROP Starts Strong : 7 Associate Department Head Rising Stars in EECS : 11 William T. Freeman Welcome to the 2013 edition of the MIT EECS Connector. I am pleased to share news Women’s Technology Program : 13 Associate Department Head of ongoing academic and research programs as well as the implementation of the Centers: hubs for collaborative action : 14 2012 EECS Strategic Plan. Over the past academic year we launched several major bigdata@CSAIL : 14 CONTACT initiatives that have already made a positive impact on our faculty, students, staff, Wireless@MIT : 15 the MIT EECS Connector and alumni. The EECS Department at MIT continues to lead internationally in Connection Science and Engineering : 17 Room 38-401 education and research, establishing the basis for tomorrow’s breakthrough MIT/MTL Center for Graphene Devices and 2D Systems : 18 77 Massachusetts Avenue technologies. Center for Excitonics : 19 Cambridge, MA 02139 The new SuperUROP program, launched in September 2012, features a year-long Research Lab News : 21 [email protected] advanced research experience during which undergraduate students (juniors and CSAIL: From the Integrated Circuit to the Internet: Bridging Engineering and the Social Sciences, seniors) focus on a challenging research problem. The program provides mentor- Constantinos Daskalakis : 21 Editor: Patricia A. -

Campus Walking Tour

(O) MIT Museum O 265 Massachusetts Avenue NE25 M a 36 M L s s 51 a c h 39 38 u 32 76 MIT Chapel (Building W15). You are welcome to enter the non-denominational Chapel unless it is MIT Media Lab (Building E14) and List Visual Arts Center (Building E15). The Media Lab s e t t 37 s being used for a service or function. The Chapel was designed by renowned architect Eero Saarinen in contains more than 25 research groups working on 350+ projects that range from neuroengineering to A 35 v Campus e NE20 ssar Str W33 Va eet n 1955. Inside, a metal altarpiece created by legendary sculptor Harry Bertoia is used to scatter light that how children learn to developing the city car of the future. The first floor is open to visitors. u e enters the space from the beautiful domed skylight. 33 24 E19 The List Visual Arts Center, MIT’s contemporary art museum, collects, commissions, and presents 31 M W31 ain Fun Fact: The Chapel features a 1,300-pound bell cast at MIT’s Merton C. Flemings Metals provocative, artist-centric projects that engage MIT and the global arts community. The List is free and 17 26 K Stre Walking Tour W32 68 et Processing Laboratory. open to the public. For more information visit listart.mit.edu. B E18 W35 9 12 North Court 13 N E17 Fun Fact: The List has a Campus Loan Art Program and makes artwork from their permanent Welcome to MIT! 54 E25 Kendall/MIT W20 66 Red Line Hart Nautical Gallery of the MIT Museum (Building 1, through the doorway at 33 Mass. -

Campus Walking Tour

(O) MIT Museum O 265 Massachusetts Avenue NE25 M a 36 M L s 51 s a c h 39 38 76 u 32 MIT Chapel (Building W15). You are welcome to enter the non-denominational Chapel unless it is MIT Media Lab (Building E14) and List Visual Arts Center (Building E15). The Media Lab s e t t 37 s being used for a service or function. The Chapel was designed by renowned architect Eero Saarinen in contains more than 25 research groups working on 350+ projects that range from neuroengineering to A 35 v Campus e NE20 ssar Str W33 Va eet n 1955. Inside, a metal altarpiece created by legendary sculptor Harry Bertoia is used to scatter light that how children learn to developing the city car of the future. The first floor is open to visitors. u e enters the space from the beautiful domed skylight. 33 24 E19 The List Visual Arts Center, MIT’s contemporary art museum, collects, commissions, and presents 31 M W31 ain Fun Fact: The Chapel features a 1,300-pound bell cast at MIT’s Merton C. Flemings Metals provocative, artist-centric projects that engage MIT and the global arts community. The List is free and 17 26 K Stre Walking Tour W32 68 et Processing Laboratory. open to the public. For more information visit listart.mit.edu. B E18 W35 9 12 North Court 13 N E17 Fun Fact: The List has a Campus Loan Art Program and makes artwork from their permanent Welcome to MIT! 54 E25 Kendall/MIT W20 66 Red Line Hart Nautical Gallery of the MIT Museum (Building 1, through the doorway at 33 Mass.