Mitchell-W-City-Of-Bits.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graduationl Speakers

Graduationl speakers ~~~~~~~~*L-- --- I - I -· P 8-·1111~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ stress public service By Andrew L. Fish san P. Thomas, MIT's Lutheran MIT President Paul E. Gray chaplain, who delivered the inlvo- '54 told graduating students that cation. "Grant that we may use their education is "more than a the privilege of this MIT educa- meal ticket" and should be used tion and degree wisely - not as to serve "the public interest and an entitlement to power or re- the common good." His remarks gard, but as a means to serve," were made at MIT's 122nd com- Thomas said. "May the technol- mencement on May 27. A total ogy that we use and develop be of 1733 students received 1899 humane, and the world we create degrees at the ceremony, which with it one in which people can was held in Killian Court under live more fully human lives rather sunny skies, than less, a world where clean air The importance of public ser- and water, adequate food and vice was also emphasized by Su- shelter, and freedom from fear and want are commonplace rath- Prof. IVMurman er than exceptional." named to Proj. Text of CGray's commencement address. Page 2. Athena post In his commencement address, By Irene Kuo baseball's National League Presi- Professor Earll Murman of the dent A. Bartlett Giamatti urged Department of Aeronautics and graduates to "have the courage to Astronautics was recently named connect" with people of all ideo- the new director of Project Athe- logies. Equality will come only ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~,,4. na by Gerald L. -

MIT Press Journals

MIT Press Journals 2019 catalog Table of Contents General Information 1 Advertising 1 Journal Packages 2 Selected Books 45 Ordering Information 46 Subscription Form 47 Publishing with the MIT Press 48 Science & Technology Artificial Life 4 Computational Linguistics 5 Computational Psychiatry 6 Evolutionary Computation 7 Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 8 Linguistic Inquiry 9 Network Neuroscience 10 Neural Computation 11 Neurobiology of Language 12 Open Mind 13 Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 14 Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 15 The Arts & Humanities African Arts 16 ARTMargins 17 Computer Music Journal 18 Dædalus 19 Design Issues 20 Grey Room 21 JoDS: Journal of Design and Science 22 Leonardo 23 Leonardo Music Journal 24 The New England Quarterly 25 October 26 PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 27 Projections 28 TDR/The Drama Review 29 Thresholds 30 inside front cover Table of Contents General Information 1 Advertising 1 Journal Packages 2 Selected Books 45 Ordering Information 46 Subscription Form 47 Publishing with the MIT Press 48 Science & Technology Artificial Life 4 Computational Linguistics 5 Computational Psychiatry 6 Evolutionary Computation 7 Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 8 Linguistic Inquiry 9 Network Neuroscience 10 Neural Computation 11 Neurobiology of Language 12 Open Mind 13 Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 14 Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 15 The Arts & Humanities African Arts 16 ARTMargins 17 Computer Music Journal 18 -

Journals 2016 Catalog Directors’ Letter

MIT Press Journals 2016 catalog Directors’ Letter Dear Friends, The MIT Press celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2012, and the inclination to ponder our distinguished history remains strong, perhaps even more so this year with the change in Press leadership—Amy Brand was named Director of the MIT Press in July of 2015. The Press’s journals division, which was founded in 1972, ten years after the books division, also has a significant publishing legacy to consider, with over 80 journals published since the division’s inception. Some, such as Linguistic Inquiry and The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, have grown with us from the very beginning. Other core titles like International Security, October, The Review of Economics and Statistics and Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience joined the Press over the following decades, providing a solid base for the high-quality and innovative scholarship that our journals division is well known for. Today, we continue to push the boundaries of scholarly publishing and communication. We relish discovering new fields to publish in, and working with scholars who are establishing new domains of research and inquiry. In keeping with that spirit, the Press is proud to launch a new open access journal in 2016, Computational Psychiatry, to serve a burgeoning field that brings together experts in neuroscience, decision sciences, psychiatry, and computation modeling to apply new quantitative techniques to our understanding of psychiatric disorders. Developing new ways of delivering journal articles and providing a richer range of metrics around their usage and impact is another current effort. On our mitpressjournals.org site, the Press is providing Altmetric badges for select titles to give an improved sense of the breadth of a journal article’s reach. -

Read the Full Report

The Smoot-Hawley Fixation: Putting the Sino-US Trade War in Contemporary and Historical Perspective Simon J. Evenett1 University of St. Gallen, the St. Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade2 and CEPR 29 September 2019 This paper was published in the Journal of International Economic Law on 6 December 2019. Unfortunately, the published version excluded many of the pertinent footnotes that lawyers love and that, more importantly, support key elements of the argument. For this reason we make the full version of the paper available here. 1 Professor of International Trade and Economic Development, Department of Economics, University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, and Coordinator, the Global Trade Alert, the independent commercial policy monitor. I thank Patrick Buess, Johannes Fritz, Maxime Kantenwein, and Piotr Lukaszuk for help preparing the empirical evidence for this paper. I thank Anne van Aaken, Chad Bown, Andrew Lang, two referees, and Piotr Lukaszuk for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. I also thank Doug Irwin, Kevin O’Rourke, and Niko Wolf for checking my characterisation of the economic history literature on trade policy developments in the 1930s. All remaining errors are mine. Comments are welcome and should be sent to [email protected]. 2 Founder of the new non-profit Foundation to house the Global Trade Alert and other commercial policy- related initiatives. Abstract The extent to which the Sino-US trade war represents a break from the past is examined. This ongoing trade war is benchmarked empirically against the Smoot-Hawley tariff increase and against the sustained, covert discrimination by governments against foreign commercial interests witnessed since the start of the global economic crisis. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

The MIT Press Spring 2021 Dear Friends and Readers, Contents

The MIT Press Spring 2021 Dear Friends and Readers, Contents Books are carriers of civilization. Without books, history is silent, literature dumb, science crippled, thought and speculation at a standstill. They are engines of change, windows to the world, “lighthouses” (as a poet said) Trade 1-32 “erected in the sea of time.” Paperback Reprints 33-36 —Barbara W. Tuchman, American historian Distributed by the MIT Press University presses are critical to the academy’s core purpose to create and share knowledge. In these extraordinary times, scholars and scientists are racing to overcome a pandemic, Boston Review 37 combat climate change, and protect civil liberties even as Goldsmiths Press 38-39 they are forced to engage in escalating information warfare. With expanding misinformation and shrinking public trust in Semiotext(e) 40-43 news media, in science and academia, and in expertise more Sternberg Press 44-58 broadly, it falls to universities and mission-driven publishers to uphold sense-making and the spreading of facts—to share Strange Attractor Press 59-61 and translate credible, research-based information in ways that Terra Nova Press 62 maximize its impact on decisions that will shape the future of humanity. University presses have a central role to play in this Urbanomic 63 cause, and the MIT Press continues to be a guiding light. As Director, I am reminded daily of the power of books for posi- Academic Trade 64-68 tive change—to create more beauty, knowing, understanding, Professional 69-91 justice, and human connection in our vast and complex world. www.dianalevine.com Amy Brand All of us at the MIT Press feel a profound responsibility to use Journals 92-94 our privileged perch for good wherever we can. -

John Harvard Scholarship, 1953–1954, 1954–1955 • Phi Beta Kappa, 1955 • Harvard College Scholarship, 1955–1956

Ph.D. Economics FRANKLIN M. FISHER Harvard University Jane Berkowitz Carlton and Dennis William Carlton Professor of Microeconomics, Emeritus, Massachusetts Institute of M.A. Economics Technology Harvard University A.B. Economics Harvard University (summa cum laude) Ph.D. Dissertation A Priori Information and Time Series Analysis FELLOWSHIPS, SCHOLARSHIPS, AND PROFESSIONAL HONORS • Detur Prize, 1953 • Social Science Research Council Undergraduate Research Stipend, 1953 • John Harvard Scholarship, 1953–1954, 1954–1955 • Phi Beta Kappa, 1955 • Harvard College Scholarship, 1955–1956 • Rodgers Fellowship, 1956–1957 • Austin Fellowship, 1956–1957 • Junior Fellow of the Society of Fellows, Harvard University, 1957–1959 • Fellow of the Econometric Society, 1963–Present • Irving Fisher Lecturer at Econometric Society Meetings, Amsterdam, September 1968 • Operations Research Society of America Prize for best paper dealing with a military subject published in Operations Research, 1967 • Fellow of American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1969–Present • Council Member of the Econometric Society, 1972–1976 • John Bates Clark Award, American Economic Association, 1973 • F. W. Paish Lecturer, Association of University Teachers of Economics, Sheffield, England, April 1975 • Vice President of the Econometric Society, 1977–1978 • David Kinley Lecturer, University of Illinois, 1978 FRANKLIN M. FISHER Page 2 • President of the Econometric Society, 1979 • Fellowship, John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, 1981–1982 • Erskine Fellow, University of Canterbury, summer -

NR Science Cities ENG

“Science Cities” : Science Campuses and Clusters in 21st Century Metropolises > Keynote IAU-île de France 1 March 2010 “Science Cities” : Science Campuses and Clusters in 21st Century Metropolises > Keynote A study examining a pressing issue in Paris Ile-de-France Creating science campuses that draw on an landscape of graduate studies in Ile-de exchange of knowledge generated by France. They not only differ in terms of the different disciplines is a major focus for all scientific disciplines they house and the cities seeking to attract innovative and extent of the building projects, but also creative R&D activities to their regions. These regarding each specific territorial context. places are widely viewed as essential Issues relating to urban integration and the resources for the development of high-tech construction timeframe for these two business clusters, which are pathways to campuses will therefore, by definition, be value creation and highly qualified jobs. Yet very different, especially as the surface this is not always the case, as demonstrated areas, capacity and access via public by the mixed results in terms of start-up and transportation are not comparable. jobs creations at the large Adlershof project in Berlin, or the problematic gestation Condorcet will concentrate on the social experienced by the Saclay technopole sciences and will occupy 180,000 sq.m of development for twenty years. floor space and approximately 7.5 hectares (18.4 acres) on either side of the Boulevard The selectioni of the Saclay and Condorcet Périphérique, to the northern edge of the city projects for the “Opération Campus”, a vast of Paris. -

Journals 2017 Catalog Contents

MIT Press Journals 2017 catalog Contents Table of Contents General Information iii Advertising iv Package Prices v Selected Books 38 Ordering Information 40 Subscription Form 41 Publishing with the MIT Press 42 Science & Technology Artificial Life 1 Computational Linguistics 2 Computational Psychiatry 3 NEW Evolutionary Computation 4 Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 5 Linguistic Inquiry 6 Nautilus 7 Network Neuroscience 8 NEW Neural Computation 9 Open Mind: Discoveries in Cognitive Science 10 NEW Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 11 The Arts & Humanities African Arts 12 ARTMargins 13 Computer Music Journal 14 Dædalus 15 Design Issues 16 Grey Room 17 JoDS: Journal of Design and Science 18 NEW Leonardo 19 Leonardo Music Journal 20 The New England Quarterly 21 October 22 PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 23 TDR/The Drama Review 24 International Affairs, History & Political Science Global Environmental Politics 25 International Security 26 Journal of Cold War Studies 27 The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 28 Perspectives on Science 29 Economics American Journal of Health Economics 30 Asian Development Review 31 Asian Economic Papers 32 Education Finance and Policy 33 The Review of Economics and Statistics 34 Idea Commons About Idea Commons 35 ARTECA 36 MIT CogNet 37 On the Cover © Penousal Machado and Tiago Martins, Untitled, 2014; a nonphotorealistic rendering of a flamenco dancer created by an ant species evolved using Photogrowth. See article in Leonardo 49:3 by Penousal Machado et al. New for 2017 FOUR additions to our Open Access program H i JoDS: Journal of Design and Science p. 18 “JoDS is about both the design of science, and the science of design.” —Joi Ito, MIT Media Lab Computational Psychiatry p. -

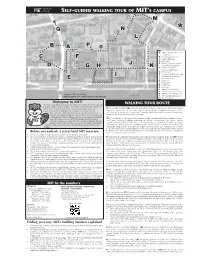

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street. -

Learning Spaces Diana Oblinger EDUCAUSE

The College at Brockport: State University of New York Digital Commons @Brockport Brockport Bookshelf 2006 Learning Spaces Diana Oblinger EDUCAUSE Joan K. Lippincott The College at Brockport, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf Part of the Databases and Information Systems Commons, and the Interior Architecture Commons Repository Citation Oblinger, Diana and Lippincott, Joan K., "Learning Spaces" (2006). Brockport Bookshelf. 78. http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/bookshelf/78 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @Brockport. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brockport Bookshelf by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @Brockport. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning Spaces Diana G. Oblinger, Editor Learning Spaces Diana G. Oblinger, Editor ISBN 0-9672853-7-2 ©2006 EDUCAUSE. Available electronically at www.educause.edu/learningspaces Learning Spaces Part 1: Principles and Practices Chapter 1: Space as a Change Agent Diana G. Oblinger • Acknowledgments • Endnote • About the Author Chapter 2: Challenging Traditional Assumptions and Rethinking Learning Spaces Nancy Van Note Chism • Changing Our Assumptions • Intentionally Created Spaces • Opportunities and Barriers • Moving Forward • Hope for the Future • Endnotes • About the Author Chapter 3: Seriously Cool Places: The Future of Learning-Centered Built Environments William Dittoe • Marcy • The Learner-Centered Difference • Endnotes • About the Author Chapter 4: Community: The Hidden Context for Learning Deborah J. Bickford and David J. Wright • Why Community? • Community as a Context for Learning • Conclusion • Endnotes • About the Authors Chapter 5: Student Practices and Their Impact on Learning Spaces Cyprien Lomas and Diana G. -

Then, Now, and Beyond

ThenNowAndBeyond052419.docx - Last edited 5/24/19 2:40 PM EDT Then, Now, and Beyond We were there 1960-2019 A book of essays about how the world has changed written by members of the MIT Class of 1964 ii Copyright @ 2019 by MIT Class of 1964 Class Historian and Project Editor-in-chief: Bob Popadic Editors: Bob Colvin, Bob Gray, John Meriwether, and Jim Monk Individual essays are copyright by the author. A Note on Excellence by F. G. Fassett From the June 1964 issue of MIT Technology Review, © MIT Technology Review Authors Jim Allen Bob Blumberg Robert Colvin Ron Gilman Bob Gray Conrad Grundlehner Leon Kaatz Jim Lerner Paul Lubin John Meriwether Jim Monk Lita Nelsen Bob Popadic David Saul Tom Seay David Sheena Don Stewart Bob Weggel Warren Wiscombe iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ iii Preface ................................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... ix Arts and Culture .................................................................................................................................... 1 Then and Now - Did our world get better? Maybe yes. ...................................................................... 2 Period of Awareness .....................................................................................................................................................