Eating Transnationally: Mexican Migrant Workers in Aiaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meat Products and Consumption Culture in the East

Meat Science 86 (2010) 95–102 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Meat Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/meatsci Review Meat products and consumption culture in the East Ki-Chang Nam a, Cheorun Jo b, Mooha Lee c,d,⁎ a Department of Animal Science and Technology, Sunchon National University, Suncheon, 540-742 Republic of Korea b Department of Animal Science and Biotechnology, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, 305-764 Republic of Korea c Division of Animal and Food Biotechnology, Seoul National University, Seoul, 151-921 Republic of Korea d Korea Food Research Institute, Seongnam, 463-746 Republic of Korea article info abstract Article history: Food consumption is a basic activity necessary for survival of the human race and evolved as an integral part Received 29 January 2010 of mankind's existence. This not only includes food consumption habits and styles but also food preparation Received in revised form 19 March 2010 methods, tool development for raw materials, harvesting and preservation as well as preparation of food Accepted 8 April 2010 dishes which are influenced by geographical localization, climatic conditions and abundance of the fauna and flora. Food preparation, trade and consumption have become leading factors shaping human behavior and Keywords: developing a way of doing things that created tradition which has been passed from generation to generation Meat-based products Food culture making it unique for almost every human niche in the surface of the globe. Therefore, the success in The East understanding the culture of other countries or ethnic groups lies in understanding their rituals in food consumption customs. -

Diccionario De Lengua De Señas

DICCIONARIO BÁSICO DE LA LENGUA DE SEÑAS COLOMBIANA INSTITUTO CARO Y CUERVO República de Colombia DEPARTAMENTO DE LEXICOGRAFÍA Ministerio de Educación Nacional MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN NACIONAL Dra. María Cecilia Vélez White Ministra de Educación Dra. Juana Inés Díaz Tafur Viceministra de Educación Dra. María Camila Rivera Caicedo Delegada de la Ministra de Educación Nacional Presidenta del Consejo Directivo del INSOR INSTITUTO NACIONAL PARA SORDOS, INSOR Rubiela Álvarez Castaño Directora General (E) Gustavo Guzmán Lozano Subdirector General Sandra Castro Subdirectora de Investigación 2006 DICCIONARIO BÁSICO DE LA LENGUA DE SEÑAS COLOMBIANA Participantes INSTITUTO CARO Y CUERVO Director General: Dr. Hernando Cabarcas Antequera (2005-2006) Dr. Ignacio Chaves Cuevas (2000-2004) Directoras del Proyecto: María Clara Henríquez Guarín Nancy Rozo Melo Asesor Académico: Edilberto Cruz Espejo Redactores: María Clara Henríquez Guarín Sandra Viviana Mahecha Mahecha Jorge Malaver Cruz Geral Eduardo Matéus Ferro Eufrocina Rojas Arregocés Nancy Rozo Melo Ivonne Elizabeth Zambrano Gómez INSTITUTO NACIONAL PARA SORDOS (INSOR) Directora General: Rubiela Álvarez (2005-2006) Luz Mary Plaza (2000-2004) Interventores: Paulina Ramírez Jaime Collazos Colaboradores: Sheila Jinnet Parra Niño Paulina Ramírez Intérpretes: Cristian Barón Cañón Mariana Cárdenas Martha Lucía Contento Derly Tatiana Gordillo Segura Alejandro Piñeros Anexo gramatical: Alejandro Oviedo Informantes sordos Carolina Álvarez René Carvajal Corpus Bogotá: Josué Jacobo Cely Orlando García Maldonado -

Drink & Beverage Tapioca Drink

Drink & Beverage Tapioca Drink Thai Iced Tea Vietnamese Iced Coffee Lunch special Monday – Friday: 11 am – 3pm, excluded Weekends & Holidays Prices are subject to change without notice All rights reserved. No part of this menu may be copied in any form or by any means without permission from the BEIJING HOUSE Appetizers (1) Organic (6) (2) (Gỏi Cuốn) (2) (6) (6) (Steamed, Deep Fried or Pan Fried) ( Xíu Mại) (5) ả (Shrimp Dumpling) (4) Chinese Entrée (Dark Meat (Chicken, Beef & Shrimp) Sweet & Sour Chicken Mongolian Beef Tofu with Vegetable Sesame Chicken Kung Pao Shrimp General Tso Chicken Beef with Broccoli (Chicken, Beef & Shrimp) (Chicken, Beef & Shrimp) Japanese Cuisine Mixed vegetable sautéed in teriyaki sauce, topped with sesame seeds Chicken and mushroom sautéed in hibachi sauce, topped with sesame seeds Chicken and broccoli sautéed in teriyaki sauce, topped with sesame seeds Vietnamese Cuisine ở : ị ướ Rice vermicelli with grilled sliced pork ả Rice vermicelli with stir fried lemon grass chicken ị ướ ả ở Đặ ệ Rice vermicelli with grilled sliced pork & vegetable (With medium-well thinly sliced eyed- round beef, spring roll Beef flank, beef tendon & beef meat ball) ở ị ướ Rice vermicelli with grilled sliced pork & shrimps (Medium-well thinly eyed -round beef) ị ướ ả ở ạ (With well-done beef flank) Rice vermicelli with grilled sliced pork, shrimps ở (With beef meat balls) & vegetable spring roll ở ả Rice vermicelli with stir fried lemon grass beef (With medium-well thinly sliced eyed- round beef & beef meat balls) ả ở ạ Rice vermicelli -

De Rosh Hashanah Panes Picadas - Pollo

MENÚ DE ROSH HASHANAH PANES PICADAS - POLLO Hala trenza $2.50 Hala Dulce en espiral $4.50 Cordon blue relleno de pastrami $36.00 Alita Agridulce $25.00 12 Onzas 12 Onzas 24 Unidades 1/2 Bandeja Hala trenza integral $3.00 Loaf de miel con manzana $8.00 Empanadita de pollo $24.00 Buffalo Wings (picante) $25.00 12 Onzas Unidad 24 Unidades 1/2 Bandeja Hala trenza con chocolate $4.00 Strudel de manzana en masa filo $12.00 Nuggets $25.00 Empanada de maiz, rellena de $26.00 12 Onzas Unidad 1.5 Libras papa y pollo (tipo colombiana) 24 Unidades Mini Hala Roll $1.00 Bandeja de panes $15.00 Pop Nuggets al limón $27.00 3 Onzas (Pan de 7 granos, Pan de campo, Pan de 1.5 libras (70 unidades aprox.) nueces, Palitroquis Varios) - Unidad BERAJOT PICADAS - PARVE Zapallo - Berajot $18.00 Tortita de Acelga - Berajot $1.00 Mohara de hongos $28.00 Empanadita de Atún $24.00 32 Onzas Unidad 24 Unidades 24 Unidades Frijolitos Lubie - Berajot $6.00 Cabeza de pescado - Berajot $15.00 Mohara de espinaca $26.00 Empanadita de tuna con vegetales $25.00 24 Onzas Unidad 24 Unidades (Unidad) 24 Unidades Tortita de Puerro - Berajot $1.00 Kibbe de hongos $29.00 Empanadita de hongos $28.00 Unidad 24 Unidades 24 Unidades Sandwichito de huevo $18.00 Empanadita de espinaca $28.00 24 Unidades PICADAS - CARNE DE RES 24 Unidades Sandwichito de tuna $19.00 Knishe de papa $22.00 24 Unidades 24 Unidades Empanadita de Carne $24.00 Empanada tipo colombiana $26.00 24 Unidades 24 Unidades Empanadita de pastrami $32.00 Lajma B’ajin $24.00 24 Unidades 24 Unidades PICADAS - LECHE (Halav -

1. Portada, Titulos, Dedicatoria, Agradecimientos FINAL

Facultat de Biociències Departament de Genètica i de Microbiologia Grup de Mutagènesi DAÑO GENÉTICO EN MADRES Y EN SUS RECIÉN NACIDOS. FACTORES MODULADORES Tesis doctoral Naouale El-Yamani DAÑO GENÉTICO EN MADRES Y EN SUS RECIÉN NACIDOS. FACTORES MODULADORES El presente trabajo se ha realizado en el Grup de Mutagènesi del Departament de Genètica i de Microbiologia de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona bajo la dirección del Dr. Ricard Marcos y subvencionado por el Proyecto de Investigación NewGeneris: Newborns and Genotoxic Exposure Risks (Food-CT-2005-016320). Memoria presentada por Naouale El-Yamani para optar al grado de Doctora por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallés), Noviembre de 2011. V°B° Autora Director del trabajo de Tesis Dr. Ricard Marcos Dauder Naouale El-Yamani Catedrático de Genética UAB No existen más que dos reglas para escribir: tener algo que decir y decirlo. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) A mi familia Agradecimientos Este trabajo de Tesis realizado en la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona es un esfuerzo en el cual, directa o indirectamente, participaron distintas personas opinando, corrigiendo, teniéndome paciencia, dando ánimo, acompañando en los momentos de crisis y en los momentos de felicidad. Este trabajo me ha permitido aprovechar la competencia y la experiencia de muchas personas que deseo agradecer en este apartado. En primer lugar, a mi director de Tesis, Dr. Ricard Marcos Dauder, mi más amplio agradecimiento por haberme confiado este trabajo en persona, por su paciencia ante mi inconsistencia, por su valiosa dirección y apoyo para seguir este camino de Tesis y llegar a la conclusión del mismo. -

Chinese Fresh & Hot Food, Grab and Go Menu Hawaiian Bbq Menu

Chinese fresh & hot Hawaiian bbq menu food, grab and go menu * All plates are freshly cooked * Special combos and large plates are served make your own combo plate(s) with 2 scoops of rice & 1 scoop of macaroni * Small chinese combo (1 side, 1 item) salad $9.18 625 oak grove ave. unit b * small plates are served with 1 scoop of rice menlo park, ca 94025 * 1-item chinese combo $9.90 & 1 scoop of macaroni salad. located between mattress discounters and the (2 sides, 1 item) * Make any sized meal healthy by replacing the u.s. post office * 2-item chinese combo $11.10 rice and mac salad with steamed super green (2 sides, 2 items) veggies Regular Hours: Mon-Sat 10:30am - 8:00pm Closed Sunday (Catering available with step 1 - choose your side(s) advanced notice) hawaiian bbq special combos: -white rice #1 Hawaiian BBQ Chicken $13.20 -chicken salad #2 Loco Moco $14.40 Telephone: (650) 561-4296 -fried rice #3 Kalua Pig & Pork Lau Lau Combo $16.80 -chow mein #4 Hawaiian BBQ Mix Plate $15.60 e-mail: [email protected] -chow fun (Includes: BBQ Shortribs, Chicken, & Beef) website: http://www.philskitchen.net -rice noodles #5 Chicken Katsu $13.20 #6 Seafood & BBQ Combo $16.80 “like” us on facebook! step 2 - choose your item(s) (choice of meat: BBQ Shortribs, Chicken, or Beef) search “phil’s treasure pot” or (items available may vary) visit: http://www.facebook.com/ #7 Teriyaki salmon $20.39 philstreasurepot -MIXED VEGETABLES W/ TOFU (VEGETARIAN) -EGGPLANT IN GARLIC SAUCE (MILD) SAIMIN *all prices are subject to change* (VEGETARIAN) (hawaiian noodle soup) 32 OZ. -

Saucy Mongolian Beef with Garlic Vegetables

HelloFresh.com.au [email protected] | (02) 8188 8722 [email protected] WK20 2016 Saucy Mongolian Beef with Garlic Vegetables Mongolian beef: it’s been a family Chinese restaurant staple for Prep: 15 mins years, and it’s time to master it in your own kitchen. For the perfect Cook: 15 mins level 1 result, make sure your wok is searing hot before adding the beef Total: 30 min contains strips. Don’t be afraid to only cook the veg for a few minutes either nut free - a little bite to them is definitely what you want here. crustacea Pantry Items Soy Sauce Brown Sugar Garlic Ginger Oyster Sauce Beef Strips Plain Flour Water Vegetable Oil Jasmine Rice Red Capsicum Broccoli Spring Onions JOIN OUR PHOTO CONTEST #HelloFreshAU QTY Ingredients Ingredient features 2 tbs salt-reduced soy sauce * in another recipe 1 tbs brown sugar * 1 tbs plain flour * * Pantry Items 2 cloves garlic, peeled & crushed 1 knob ginger, peeled & finely grated Pre-preparation 2 tbs oyster sauce 2 tbs warm water * Nutrition per serve 600 g beef strips Energy 2500 Kj 1 ½ cups Jasmine rice, rinsed well Protein 42.8 g 6 cups water * Fat, total 14.9 g 2 tbs vegetable oil * -saturated 4.1 g 1 red capsicum, thinly sliced Carbohydrate 70.6 g 1 head broccoli, florets chopped into small bite-sized pieces -sugars 8.7 g 1 bunch spring onions, finely sliced Sodium 938 mg 1 You will need: chef’s knife, chopping board, garlic crusher, vegetable peeler, grater, tongs, medium bowl, plate, medium saucepan, large wok. -

December Menu

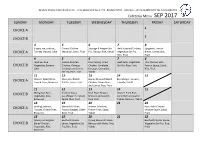

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School - Jl. Bujanggamanik Kav 2, KPB - Bandung 40553 – Indonesia - Tel: 62-22-86813949/ Fax: 62-22-86813953 Cafeteria Menu SEP 2017 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 CHOICE A 1 CHOICE B 4 5 6 7 8 Sloppy Joe, Lettuce, Cheesy Chicken Sausage & Pepper Stir Herb Roasted Chicken, Spaghetti, French CHOICE A Tomato, Banana Cake Macaroni, Salad, Fruit Fry, Pakcoy, Rice, Yakult Vegetable Stir Fry, Bread, Carrot Stick, Rice, Fruit Fruit 4 5 6 7 8 Japchae, Rice, Korean Roasted Nasi Kuning, Fried Beef Kalio, Vegetable Thai Chicken with CHOICE B Vegetable, Banana Chicken, Chinese Chicken, Omelette, Stir Fry, Rice, Fruit Peanut Sauce, Salad, Cake Cabbage and Carrot Kerupuk, Cucumber, Rice, Fruit Stir Fry, Rice, Fruit Yakult 11 12 13 14 15 CHOICE A Chicken Salad Wrap, Meatloaf, Boiled Honey Mustard Baked Beef Burger, Lettuce, French Fries, Brownies Potato, Salad, Fruit Chicken, Green Bean Tomato, Yakult and Carrot, Rice, Fruit 11 12 13 14 15 CHOICE B Mongolian Beef, Chicken Katsu, Beef Black Pepper, Chicken Fried Rice, Vegetable, Rice, Cauliflower in Tomato Broccoli and Carrot, Cucumber and Carrot Brownies Sauce, Rice, Fruit Rice, Fruit Pickles, Kerupuk, Yakult 18 19 20 21 22 CHOICE A Hotdog, Lettuce, Mexicali Chicken, Wiener Schnitzel, Pasta with Creamy Tomato, French Fries, Potato Wedges, Green French Fries, Salad, Chicken Sauce, Salad, Brownies Bean, Fruit Yakult Fruit 18 19 20 21 22 Honey Lemongrass Beef with Hoisin Nyang Nyeom Chicken, Beef with Oyster Sauce, CHOICE B Baked Chicken, Sauce, -

Chinese Menu Welcome Back to Goldie’S Casino We Have Reduced Our Menu for a Short Time As We Transition Into Normal Operations

Chinese Menu Welcome Back to Goldie’s Casino We have reduced our menu for a short time as we transition into normal operations. We will be back to normal shortly and appreciate you coming back to visit us after this long break. Please remember to follow the new COVID-19 Prevention Guidelines posted throughout the casino while enjoying your visit. APPETIZERS CLAY HOT POT 1. Salt & Pepper Prawns 椒盐焗中虾 $18 39. Beef Brisket Hotpot 柱侯牛腩煲 $20 2. Salt & Pepper Pork Chop 椒盐焗肉排 $15 3. Salt & Pepper Chicken Wing 椒盐焗鸡翼 $15 CHOW MEIN 盐椒豆腐 4. Salt & Pepper Tofu $13 41. House Special Chow Mein 招牌炒麵 $15 叉烧 5. Chinese BBQ Pork $12 42. Seafood Chow Mein 海鲜炒麵 $16 酥炸春卷 6. Deep Fried Egg Rolls $8 43. Beef Chow Mein 牛肉炒麵 $13 窝貼 7. Pot Stickers $8 44. Chicken Chow Mein 鸡球炒麵 $13 45. Soy Sauce Chow Mein 豉油皇炒麵 $13 SOUP 9. Beef Brisket Noodle Soup 牛腩汤面 $18 CHOW FOON 京都酸辣汤 10. Hot & Sour Soup $12 46. Seafood Chow Foon 海鲜炒河 $16 雲吞汤 11. Wonton Soup $12 47. Chicken Chow Foon 鸡球炒河 $13 雲吞汤麵 12. Wonton Noodle Soup $12 48. Beef Chow Foon (Dry) 干炒牛河 $13 49. Singapore Noodle 星洲炒米 $13 FRIED RICE 14. Shrimp Fried Rice 虾仁炒饭 $14 FISH 扬洲炒饭 15. House Special Fried Rice $14 55. Pompano & Black Bean Sauce 豉汁金仓鱼 $23 鸡炒饭 16. Chicken Fried Rice $12 56. Braised Pompano Fish 红烧金仓鱼 $23 叉烧炒饭 17. BBQ Pork Fried Rice $12 57. Braised Tilapia Fish 红烧侧鱼 $23 58. Tilapia & Black Bean Sauce 豉汁鲫鱼 $23 VEGETABLE 19. Chinese Broccoli with Garlic 蒜蓉芥兰 $12 PRAWN 20. -

H Erram Ien Tas D El Facilitad

Herramientas del facilitador: Guía de bolsillo, Apoyo a las pequeñas empresas forestales ¡sin complicaciones! Herramientas delHerramientas facilitador Las pequeñas empresas forestales componen hasta un 80-90% del número de Apoyo a las pequeñas empresas forestales: Herramientas del facilitador empresas y más del 50% del empleo del sector forestal en la mayoría de los países en desarrollo. Apoyarlas para que gestionen los bosques de forma sostenible y provechosa es esencial para los esfuerzos globales de mejorar la Aplicación de las Leyes Forestales, Gobernanza y Comercio (FLEGT) y reducir las emisiones por deforestación y degradación (REDD). El apoyo también resulta crucial para la reducción de la pobreza, puesto que son estas pequeñas empresas forestales las que acumulan beneficios localmente, ayudan a garantizar los derechos comerciales sobre los recursos locales, potencian el espíritu empresarial local y las perspectivas de empleo, fomentan la creación de capital social, generan una mayor responsabilidad local sobre el medio ambiente propicia para la adaptación al cambio climático y la mitigación de sus efectos y conservan las preferencias culturales y la diversidad. Estas herramientas han sido concebidas como respuesta a las necesidades expresadas por los miembros de los países de la alianza Forest Connect, una alianza de individuos e instituciones de más de 50 países. Su objetivo es evitar la deforestación y reducir la pobreza vinculando mejor a las pequeñas empresas forestales sostenibles entre sí, con los mercados, proveedores de servicios y procesos normativos. El manual está pensado para dos públicos destinatarios clave: las agencias internacionales que proporcionan ayuda económica para las iniciativas de las pequeñas empresas forestales y los facilitadores de apoyo a las pequeñas empresas a nivel nacional. -

Libro De Cocina Bueno Y Barato

BUENO Y BARATO ALIMÉNTATE BIEN A 4$ AL DÍA. BUENO Y BARATO WORKMAN PUBLISHING • NUEVA YORK DESCUENTOS ESPECIALES PARA ORGANIZACIONES SIN FINES DE LUCRO Las organizaciones que deseen donar libros a personas de escasos recursos podrán disponer de la edición especial de Bueno y Barato. Se ofrecen importantes descuentos por compras en grandes cantidades de 10 o más ejemplares. Por favor envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected] para obtener más información. Traducción Copyright © 2017 por Leanne Brown Copyright © de fotos por Leanne Brown y Dan Lazin Todos los derechos reservados. El autor publicó anteriormente partes de este libro bajo licencia de Creative Commons. Los términos de la licencia de Creative Commons se refieren solamente a las partes del libro en esa edición. Ninguna parte de este libro puede ser reproducida—ya sea por medios mecánicos, electrónicos o de cualquier otra índole, incluido el fotocopiado—a no ser que medie permiso por escrito del editor. Publicado simultáneamente en Canadá por Thomas Allen & Son Limited. Una versión anterior de este libro fue distribuida bajo licencia Atribución-No comercial-Compartir igual 4.0 de Creative Commons. Para obtener más información, visite creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0. Los datos de Catalogación en la fuente de la Biblioteca del Congreso de los Estados Unidos están disponibles. ISBN 978-1-5235-0118-2 Diseño de Janet Vicario; puesta en papel de Gordon Whiteside Foto de portada de Leanne Brown Otras fotos cortesía de: página xvi (de arriba abajo): pixelrobot/fotolia, lester120/fotolia, arinahabich/fotolia, komodoempire/fotolia, simmittorok/fotolia, taiftin/fotolia; página xvii (de arriba abajo): Tarzhanova/fotolia, Workman Publishing, Viktor/fotolia, photos777/fotolia, pioneer/fotolia, Andy Lidstone/fotolia. -

2 Carbohydrate 1 Main Course 1 Lauk Pendamping 1 Soup 1 Sayur 1 Menu Pelengkap (Sambal & Kerupuk)

POKINOMETRY BUFFET PACKAGES: BUFFET REGULAR • BUFFET REGULAR A (Chicken menu selection) • BUFFET REGULAR B (Meat and seafood selection) BUFFET REGULAR A (75.000/pax) 2 Carbohydrate 1 Main course 1 Lauk pendamping 1 Soup 1 Sayur 1 Menu pelengkap (sambal & kerupuk) 1 Minuman (Mineral water) BUFFET REGULAR B (85.000/pax) 2 Carbohydrate 1 Main course 1 Lauk pendamping 1 Soup 1 Sayur 1 Menu pelengkap (sambal & kerupuk) 1 Buah/minuman BUFFET PREMIUM • BUFFET PREMIUM A (2 Carbs and 1 main course) • BUFFET PREMIUM B (2 Carbs and 2 Main course) BUFFET PREMIUM A (110.000/pax) 2 Carbohydrate 1 Main course 1 Lauk pendamping 1 Menu sayuran 1 Menu pelengkap 1 Soup 1 Minuman 1 Buah BUFFET PREMIUM B (125.000/pax) 2 Carbohydrate 2 Main course 1 Lauk pendamping 1 Menu sayuran 1 Menu pelengkap 1 Soup 1 Minuman 1 Buah/ dessert MENU BUFFET Carbohydrate: -Steamed rice - Fragrant rice • Nasi uduk • Nasi kuning - Fried rice • Nasi goreng ayam pedas • Nasi goreng seafood • Nasi goreng ikan asin • Nasi goreng kepiting -Fried Bihun: • Bihun goreng ayam • Bihun goreng seafood - Fried noodle: • Mie goreng ayam • Mie goreng seafood • Mie goreng aceh (pedas) -Potato menu: • Potato wedges (premium) • Mashed potato (premium) • French fries • Baby potato Main course PREMIUM MENU: (Termasuk Regular menu) • Beef Teriyaki • Mongolian Beef • Beef rollade • Beef Dendeng cabai hijau • Beef Dendeng balado • Beef blackpepper • Fried calamari with sweet and sour sauce • Beef katsu with blackpepper • Dory crispy salt and pepper • Dory sweet and sour • Dory blackpepper REGULAR •