Space and Society an Introduction to the Special Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Social and Natural Opportunities for the Renewable Energy Utilization in the Koppany Valley Development Area

Social and Natural Opportunities for the Renewable Energy Utilization in the Koppany Valley Development Area Alexander Titov Kaposvar University, Faculty of Economic Science, Hungary [email protected] Kinga Szabó Kaposvar University, Faculty of Economic Science, Hungary [email protected] Bernadett Horváthné Kovács Kaposvar University, Faculty of Economic Science, Hungary [email protected] Abstract. Koppany Valley is located in one of the most underdeveloped Hungarian territories considering serious economic, social and infrastructural issues. Despite this fact, there is significant potential regarding the green energy sector if taking into account essential amount of local raw bio- material production. The estimated theoretical potential of biomass in the area is substantial, although however it is complicated to realise due to the social barriers such as lack of knowledge and low level of awareness regarding renewables among the local stakeholders. During 16 months of our research the most important social, economic and biomass production data of the examined settlements were collected primarily as well as secondary statistical data. Three hundred questionnaires were distributed in 10 rural settlements of the tested micro region. It was concentrated to three main parts of questions: general information about respondents (background information), awareness regarding renewable energy and different types of sources and a separate block considered biomass data specifically. In the questionnaire mostly Likert scale and multiple choice questions were applied. The study of social and natural opportunities for the renewable energy utilization helps to determine local economic circumstances by describing the social environment of the Koppany Valley. The main factors affecting public behavior towards local sustainable energy improvement were investigated. -

Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán És a Környező Falvak Példáján

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kaposvári Egyetem Folyóiratai / Kaposvar University: E-Journals Act Sci Soc 34 (2011): 181–196 Falucsúfolók, szállóigék és a falvak egymás közti divatja: Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán és a környező falvak példáján Lanszkiné Széles Gabriella Abstract Village-flouting, adages, and fashion differences between villag- es: an example of Fonó, Gölle, Kisgyalán, and the surrounding villages. The pop- ulation of villages has made no secret of their views about other communities; either it was a good or a bad judgment. Opinions formed of each other enhanced together- ness within their own village. The awareness of differing from the other village – manifested in fashion or action – created a strong connection between community members. The willingness to overtake the neighboring village expressed ambition and skills to advance. The aim of the data collection was to introduce folk costumes, wan- dering stories and the economy of villages based on village-flouting. Even alterca- tions and fights evolved from mockery in the beginning of the last century; but nowa- days these are devoted to the benefit of villages. Today, history is more valued, cele- brations are held in honor to village-flouting, village chorus protect their folk cos- tumes. With collaboration, the traditions of the past live on. Keywords village-flouting, folk costume, wandering stories, anecdote, com- monality, hostility, tradition Bevezetés Fonó község Somogy megye keleti részén, dombos területen, a Kapos-völgyében fekszik, Kaposvár vonzáskörzetéhez tartozik. A község közvetlenül határos északon Kisgyalán, keleten Mosdós, délen Baté, nyugaton Taszár és Zimány községekkel. -

Patalomi Hírek Patalomipatalomi Hírekhírek 1

Patalomi hírek PatalomiPatalomi hírekhírek 1 3. évfolyam, 1. szám Patalom Község Önkormányzatának Hírlevele 2009. január Tisztelt Patalomiak! Karácsony szent ünnepe mindannyiunkban megszólaltatta a szeretet örök csöngettyûjét. Ez a hang a családot, az otthon melegét juttatta eszünkbe. Az ünnep hangulatában a másik emberre figyeltünk és arra gondoltunk, hogy mit nyújthatnánk szeretteinknek és azoknak, akik fontosak számunkra. Ez a mi leg- emberibb értékünk. Az az Ember, aki nem csak saját magáért él, aki igazi harmóniát tud teremte- ni belsõ világában, saját lelkében és környezetében egyaránt. Ahol harmónia, béke, szeretet van, ott meghitt, bensõséges kapcsolatokra épülõ családot, kö- zösséget lehet teremteni. Ezen gondolatok jegyében kívánok Önöknek sikeres, eredményekben gaz- dag, boldog új esztendõt. Patalom, 2009. január 1. Tisztelettel: Keszler Ferenc polgármester Ballag már az esztendõ, vissza-visszanézve, Újévi köszöntõ nyomában az öccse jõ, vígan fütyörészve. Beéri az öreget s válláról a terhet legényesen leveszi, Békés álmainkban ne csalódjunk soha pedig még csak gyermek. Oltalmazzon minket angyalok mosolya Lépegetnek szótlanul, s mikor éjfél eljõ, Lelkünkben béke és szeretet virítson férfiasan kezet fog Múlttal a Jövendõ. Düh és gaz álnokság meg ne szomorítson Ostoba szólamra ne hajoljon szívünk Magyar szilveszteri babonák Gazdagság kísérje minden vidám léptünk • Ha nem falunk fel mindent szilveszterkor, akkor az újesztendõben sem fogunk hiányt szenvedni. Útjaink vigyenek igaz célunk felé • Ne feledjük, hogy tilos baromfihúst ennünk, mert a baromfi hátra- Jövendõnk munkája ne váljon keresztté kaparja a szerencsénket. • Disznóhúst együnk, mert a disznó viszont kitúrja a szerencsét. Éjszaka pompásan ragyogjon csillagod • A gazdagságot sokfajta rétessel lehet hosszúra nyújtani. • Régi szokás az egész kenyér megszegése is, hogy mindig legyen a Veled lehessek, amikor csak akarod családnak kenyere. -

Kaposszerdahelyi Krónika 2017. December

2017 ÉV DECEMBER IMPRESSZUM KÖSZÖNTŐ Kaposszerdahelyi Krónika Alapító és kiadó Kaposszerdahelyért Egyesület Szerkesztőség Kaposszerdahely Kapoli utca 4. 7476 Nyomás a várva várt ünnepek… Centrál Press Nyomda, Ó Minden évben újra- és újraéljük a készülődés Kaposvár bizsergető izgalmát, az ajándékozás gyönyörűségeit, a titkolózás, a várakozás szelíd boldogságát és az együttlét örömeit. Kiadásért felel Mester József Az előkészületek első lépéseként kürtöljük össze a családi kupaktanácsot, hogy mindenki elmondhassa vágyait, kívánságait, aztán kiderül, hogy mindenkinek van valami kiváló adottsága: ki a vásárlás bajnoka, ki a Főszerkesztő diótörők gyöngye, ki a hústűzdelés mestere, ki a terítés Mester József művésze…, így gyorsan jókedvűen megy a közösen végzett munka. Az öröm különös portéka: minél többet tud adni az ember, annál több marad belőle… weboldal www.szerdahelyert.hu M E S T E R J Ó Z S E F Kaposszerdahelyért Egyesület elnöke ISSN 2060-792X A Kaposszerdahelyért Egyesület kellemes karácsonyi ünnepeket, örömökben, sikerekben gazdag boldog új évet kíván a falu lakóinak! A békesség hírnöke jön hozzánk Isten békességet akar adni mindannyiunknak. Egy olyan belső békét, amelyben nincsen harag, nincsen gyűlölet a másik iránt, hanem arról a szeretetről szól, aki megtestesült közöttünk azon a szent éjszakán, a békesség éjszakáján. Jézus azt mondja: békességet hagyok rátok, az én békémet adom nektek. De vajon készek vagyunk befogadni ezt a békességet? Kiüresítettük-e a kezünket arra, hogy Isten megajándékozzon bennünket az ő jelenlétével? Oda tudunk figyelni a másikra, vagy csak a saját gondolataink töltenek el bennünket? Észrevesszük-e a másik kiáltó szükségét? Kérjük-e Istentől, hogy nyissa meg a szemünket, hogy békességet tudjunk vinni oda, ahol viszálykodás van, hogy a gyűlölet helyébe oda tudjuk vinni a szeretetet? Isten ezt a belső békességet a vele való találkozásban adja meg, amikor csendben, lélekben leborulunk előtte. -

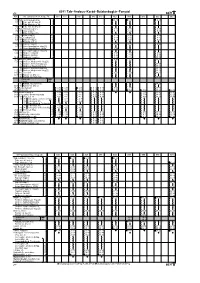

6071 Tab–Andocs–Karád–Balatonboglár–Fonyód 6071 6071

6071 Tab–Andocs–Karád–Balatonboglár–Fonyód 376 6071 Km Dél–dunántúli Közl. Közp. Zrt. 881 871 891 823 813 863 843 853 833 865 0,0 Tab, autóbusz–állomás 6 12 6 45 9 30 0,2 0,0 Tab, aut. áll. bej. út 0,9 Tab, Munkás u. 28. 0,2 0,0 Tab, aut. áll. bej. út 1,1 Tab, Kossuth Lajos u. 6 13 6 47 9 37 2,4 0,0 Zalai elág.[2] 6 15 6 49 9 39 3,2 Zala, Bótapuszta 2,4 0,0 Zalai elág.[2] 6 6 15 6 49 9 39 5,2 Tab, Csabapuszta 0 6 18 6 52 9 42 5,8 0,0 Kapolyi elág.[1] 7 6 19 6 53 9 43 1,6 Kapoly, aut. vt. 0 5,8 0,0 Kapolyi elág.[1] 6 19 6 53 9 43 8,7 0,0 Somogymeggyesi elág.[3] 4,8 Somogymeggyes, iskola 6 30 8,7 0,0 Somogymeggyesi elág.[3] 12,3 0,0 Nágocsi elág.[3] 6 40 7 03 9 51 2,8 Nágocs, faluház 6 44 7 07 9 57 16,8 6,2 Andocs, templom 6 48 7 12 10 02 16,8 Andocs, templom 6 49 7 13 10 02 17,2 0,0 Andocs, toldipusztai elág.[3] 1,3 Andocs, Németsűrűpuszta 10 05 3,2 Andocs, Nagytoldipuszta 10 08 1,3 Andocs, Németsűrűpuszta 10 10 17,2 0,0 Andocs, toldipusztai elág.[3] 10 13 18,5 Andocs, felső 6 51 7 16 10 15 23,1 0,0 Karád, vá. -

Commissie Van De Europese Gemeenschappen

COMMISSIE VAN DE EUROPESE GEMEENSCHAPPEN COM(93) 359 def Brussel, 1 september 1993 Voorstel voor een BESCHIKKING VAN DE RAAD betreffende de sluiting en de ondertekening van de overeenkomst tussen de Europese Economische Gemeenschap en de Republiek Bulgarije betreffende dte wederzijdse bescherming van en de controle op wijnbenamingen Voorstel voor een BESCHIKKING VAN DE RAAD betreffende de sluiting en de ondertekening van de overeenkomst tussen de Europese Economische Gemeenschap en de Republiek Hongarije betreffende de wederzijdse bescherming van en de controle op wijnbenamingen Voorstel voor een I BESCHIKKING VAN DE RAAD betreffende de sluiting en de ondertekening van de overeenkomst tussen de Europese Economische Gemeenschap en Roemenië betreffende de wederzijdse bescherming van en de controle op wijnbenamingen (door de Commissie ingediend) A TQEUCHTINfi 1. Bij besluit van 14.12.1992 heeft de Raad de Commissie gemachtigd met Bulgarije, Hongarije en Roemenië onderhandelingen te beginnen met het oog op de sluiting van bilaterale overeenkomsten betreffende de wederzijdse bescherming van en controle op wijnbenamingen alsmede betreffende de wederzijdse vaststelling van tariefcontingenten voor bepaalde wijnen. Dit voorstel heeft betrekking op de overeenkomsten betreffende wederzijdse bescherming en controle. 2. De onderhandelingen, die door de Commissie zijn gevoerd op basis van de onderhandelingsrichtsnoeren van de Raad, hebben geleid tot drie overeenkomsten voor wederzijdse bescherming, waarvan de voornaamste elementen als volgt kunnen worden -

2019.05.07. Vízbiztonsági Fejlesztések a KAVÍZ Kaposvári

Vízbiztonsági fejlesztések a KAVÍZ Kaposvári Víz- és Csatornamű Kft. működési területén szakértői audit alapján 2019.05.07. 1 Спасибо за внимание! Vízbiztonság „pillérei” VÍZBIZTONSÁG Jogszabályi Gazdasági Víziközmű Víziközmű- környezet környezet műszaki szolgáltató- állapot szervezet Hatósági felügyelet Befolyás? Jogszabály Költség- Pályázatok Létszám véleményezés csökkentés (KEOP, KEHOP, Szaktudás egyéb) Hatósági Árbevétel- Motiváltság kapcsolat- növelés GFT tartás, VBT VBT 2 Спасибо за внимание! Jogszabályi környezet 2011. évi CCIX. törvény (Vksztv.) 58/2013. (II. 27.) Korm. rendelet (Vhr.) 201/2001. (X. 25.) Korm. rendelet 16/2016. (V. 12.) BM rendelet … A tevékenység szabályozott! A vízközmű-szolgáltatók befolyása elhanyagolható. Hatósági felügyelet „Napi” kapcsolattartás (közegészségügy, katasztrófavédelem) Bizalmi viszony A jogszabályok meghatározzák a mozgásteret! Általánosságban nincs probléma! 3 Спасибо за внимание! Gazdasági környezet Alulfinanszírozottság: - túladóztatás - veszteséges alaptevékenység az alacsony díjak miatt Teljes költség-megtérülés elve? A díjakban meg nem térülő felújítási hányad Kényszerű vállalkozási tevékenység az árbevétel-növelés kényszere miatt a karbantartás rovására A vízközmű-szolgáltatók befolyása erősen korlátozott! Víziközmű műszaki állapot Elöregedő hálózati elemek Rekonstrukciós hányad alacsony Források korlátossága: - KEHOP: csak meghatározott vízminőségi probléma esetén - Egyéb: alacsony pályázati forrásösszeg - GFT: a használati díjak általában nem teszik lehetővé a szükséges beruházási, -

Deliverable D1.12

Deliverable D1.12 Final report on quality control and data homogenization measures applied per country, including QC protocols and measures to determine the achieved increase in data quality Contract number: OJEU 2010/S 110-166082 Deliverable: D1.12 Author: Tamás Szentimrey et al. Date: 5-06-2012 Version: final CARPATCLIM Date Version Page Report 02/10/2012 final 2 List of authors per country Hungarian Meteorological Service: Tamás Szentimrey, Mónika Lakatos, Zita Bihari, Tamás Kovács Szent Istvan University (Hungary): Sándor Szalai Central Institute of Meteorology and Geodynamics (Austria): Ingeborg Auer, Johann Hiebl Meteorological and Hydrological Service of Croatia: Janja Milković Czech Hydrometeorological Institute: Petr Štěpánek, Pavel Zahradníček, Radim Tolasz Institute of Meteorology and Water Management (Poland): Piotr Kilar, Robert Pyrc, Danuta Limanowka Ministry for Environment National Research and Development Institute for Environmental Protection (Romania): Sorin Cheval, Monica Matei Slovak Hydrometeorological Service: Peter Kajaba, Gabriela Ivanakova, Oliver Bochnicek, Pavol Nejedlik, Pavel Štastný Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia: Dragan Mihic, Predrag Petrovic, Tatjana Savic Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Institute: Oleg Skrynyk, Yurii Nabyvanets, Natalia Gnatiuk CARPATCLIM Date Version Page Report 02/10/2012 final 3 INTRODUCTION The homogenization, the data quality control and the data completion were implemented by common software on national level. According to the service contract and the accepted deliverables D1.7, D1.8, D1.11 the common method was MASH (Multiple Analysis of Series for Homogenization; Szentimrey, 1999, 2008, 2011). Between the neighbouring countries there was an exchange of the near border station data series in order to cross-border harmonization. 1. THE SOFTWARE MASHV3.03 The MASH software, which was developed for homogenization of monthly and daily data series, includes also quality control and missing data completion units for the daily as well as the monthly data. -

Communication from the Minister for National

13.6.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 187/47 Communication from the Minister for National Development of Hungary pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons (2017/C 187/14) PUBLIC INVITATION TO TENDER FOR A CONCESSION FOR THE PROSPECTION, EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION OF HYDROCARBON UNDER CONCESSION IN THE SOMOGYVÁMOS AREA On behalf of the Hungarian State, the Minister for National Development (‘the Contracting Authority’ or ‘the Minister’) as the minister responsible for mining and for overseeing state-owned assets hereby issues a public invitation to tender for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbon under a concession contract on the basis of Act CXCVI of 2011 on national assets (‘the National Assets Act’), Act XVI of 1991 on Concessions (‘the Concessions Act’) and Act XLVIII of 1993 on mining (‘the Mining Act’), subject to the following conditions. 1. The Minister will publish the invitation to tender, adjudge the bids and conclude the concession contract in coop eration with the Hungarian Office for Mining and Geology (Magyar Bányászati és Földtani Hivatal) in accordance with the Concessions Act and the Mining Act. Bids that meet the tender specifications will be evaluated by an Evaluation Committee set up by the Minister. On the recommendation of the Evaluation Committee the Minister will issue the decision awarding the concession, on the basis of which the Minister may then conclude the concession contract with the successful bidder in accordance with Section 5(1) of the Concessions Act (1). -

54 Abod Aggtelek Ajak Alap Anarcs Andocs Apagy Apostag Arka

Bakonszeg Abod Anarcs Baks Andocs Baksa Aggtelek Apagy Balajt Ajak Apostag Alap Balaton Arka Balsa 54 Barcs Bokor Berkesz Boldogasszonyfa Berzence Basal Besence Boldva Beszterec Bonnya Battonya Biharkeresztes Biharnagybajom Borota Bihartorda Biharugra Bekecs Bikal Biri Bocskaikert Botykapeterd Belecska Bodony Beleg Bodroghalom Bucsa Benk Bodrogkisfalud Buj Bodrogolaszi Beret Bojt 55 Csipkerek Cece Csobaj Dombiratos Cered Csokonyavisonta Csaholc Csaroda Dabrony Damak Csehi Csehimindszent Darvas Csengele Csenger Csengersima Demecser Dunavecse Derecske Detek Ecseg Ecsegfalva Devecser Csernely Egeralja Doba Egerbocs Doboz Egercsehi 56 Egerfarmos Fegyvernek Egyek Encs Encsencs Gadna Endrefalva Enying Eperjeske Garadna Garbolc Fiad Fony Erk Gelej Gemzse Etes Furta Geszt Fancsal Farkaslyuk Gige 57 Hirics Golop Hedrehely Hobol Hegymeg Homrogd Hejce Hencida Hencse H Heresznye Ibafa Igar Gyugy Igrici Iharos Ilk Imola Inke Halmaj Heves Iregszemcse Hevesaranyos Irota Hangony Istenmezeje Hantos 58 Kamond Kamut Kelebia Kapoly Kemecse Kemse Kaposszerdahely Kenderes Kengyel Karancsalja Karancskeszi Kerta Kaba Karcag Karcsa Kevermes Karos Kisar Kaszaper Kisasszond Kisasszonyfa 59 Kisbajom Kisvaszar Kisberzseny Kisbeszterce Kisszekeres Kisdobsza Kocsord Kokad n Krasznokvajda Kunadacs Kishuta Kiskinizs Kunbaja Kuncsorba Kiskunmajsa Kunhegyes Kunmadaras Kompolt Kismarja Kupa Kispirit Kutas Kistelek Lad 60 Magyaregregy Lak Magyarhertelend Magyarhomorog Laskod Magyarkeszi Magyarlukafa Magyarmecske Magyartelek Makkoshotyka Levelek Liget Litka Merenye Litke -

Somogy Megyei Katasztrófavédelmi Igazgatóság Siófok Katasztrófavédelmi Kirendeltség Siófoki Hivatásos Tűzoltó-Parancsnokság

SIÓFOKI HIVATÁSOS TŰZOLTÓ-PARANCSNOKSÁG Jóváhagyom: Wéber Antal tű. dandártábornok Igazgató Somogy Megyei Katasztrófavédelmi Igazgatóság Siófok Katasztrófavédelmi Kirendeltség Siófoki Hivatásos Tűzoltó-parancsnokság Beszámoló a 2017. évi tevékénységről Egyetértek: Felterjesztem: Oláh László tű. alezredes Kekecs K. Richárd tű. őrnagy Kirendeltségvezető Tűzoltóparancsnok Siófok, 2018. március 28. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ H-8600 Siófok, Somlay Artúr utca 3. H-8601 Siófok, Pf.: 94 Tel: (36-84) 310-938 Fax: (36-84) 310-509 E-mail: [email protected] A 2017. évben a Somogy Megyei Katasztrófavédelmi Igazgatóság Siófok Katasztrófavédelmi Kirendeltség Siófok Hivatásos Tűzoltó-parancsnokság ( továbbiakban: Siófok HTP) célkitűzése volt fő feladatként az állampolgárok védelme, a káresemények felszámolása, a katasztrófavédelem rendszerében a felettes szervek által tervszerűen meghatározott, valamint a kapott egyéb feladatok maradéktalan végrehajtása, a hivatásos tűzoltó-parancsnokság, valamint a felügyelete alá rendelt Balatonboglár – Balatonlelle Önkormányzati Tűzoltóság, és Tab Önkormányzati Tűzoltóság (továbbiakban ÖTP), önkéntes tűzoltó egyesületek (továbbikban ÖTE) technikai, szakmai felkészültségének ellenőrzése, annak magasabb szintre emelése, a Katasztrófavédelem hatósági tevékenységének, valamint a hatáskörébe utalt feladatokban történő részhatósági tevékenység (vízügyi hatósági feladatok, kéményseprő ipari szolgáltatás, stb.) végrehajtása Fejér, Tolna, valamint Somogy