The American Poetry Review – September/October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS by Maeve Kirk

In whatever wreckage remains Item Type Thesis Authors Kirk, Maeve Download date 24/09/2021 15:50:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6617 IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS By Maeve Kirk RECOMMENDED: Advisory Committee Chair Richard Carr, PhD Chair, Department of English --- ---^ APPROVED: ------ Todd Sherman, MFA IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts by Maeve Kirk, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2016 Abstract In Whatever Wreckage Remains is a collection of realistically styled short stories that examines both the danger and potential of change. These pieces are driven by the psychology of the men and woman roaming these pages, seeking to provide insight into the unique weight of their personal wreckage. From a woman craving motherhood who combs through forests searching for the unclaimed body of a runaway to a spitfire retiree’s struggle to accept her husband’s failing health, the individuals in these narratives are all navigating transitional spaces in their lives, often unwillingly. Along the way, they must balance the pressures of familial roles, romantic relationships, and personal histories while attempting to reshape their understanding of self. These stories explore the shifting landscape of identity, belonging, and the sometimes conflicting responsibilities we hold to others and to ourselves. v vi Dedication This manuscript is dedicated to my parents, who read me so many stories. vii viii -

![Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0056/celebrating-the-best-american-poetry-2018-at-villanova-3-450056.webp)

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova February 6, 2019 5:00 Connelly Center Cinema 6:15 (St. David’s Room) Reception and Book Signing Villanova University is honored to host the regional launch of the thirtieth anniversary edition of The Best American Poetry, guest edited by Dana Gioia, David Lehman, general editor. For three decades, the Best American Poetry has served as an annual occasion to recognize new work by American authors; inclusion is one of the great honors established and emerging poets may receive. The anthology was officially launched at New York University, in September 2018, but Villanova now brings together six of the anthology’s authors, along with David Lehman, for an evening of reading, discussion, and fellowship on our campus. David Lehman will chair the event, which will feature short readings from six poets: Maryann Corbett, Ernest Hilbert, Mary Jo Salter, Adrienne Su, Ryan Wilson, and Villanova’s own James Matthew Wilson. The public is warmly invited to this special evening to celebrate the achievement of contemporary letters and to join us for food and conversation afterwards. This event is sponsored by the Honors Program, the Villanova Center for Liberal Education, the Department of English, and the Department of Humanities. For more information, contact James Matthew Wilson, at [email protected] About the poets Maryann Corbett was born in Washington, DC, and grew up in northern Virginia. She earned a BA from the College of William and Mary and an MA and PhD from the University of Minnesota. She has published three books of poetry: Breath Control (2012); Credo for the Checkout Line in Winter (2013), which was a finalist for the Able Muse Book Prize; and Mid Evil (2014), the winner of the Richard Wilbur Award. -

The Mid-Twentieth-Century American Poetic Speaker in the Works of Robert Lowell, Frank O’Hara, and George Oppen

“THE OCCASION OF THESE RUSES”: THE MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN POETIC SPEAKER IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT LOWELL, FRANK O’HARA, AND GEORGE OPPEN A dissertation submitted by Matthew C. Nelson In partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2016 ADVISER: VIRGINIA JACKSON Abstract This dissertation argues for a new history of mid-twentieth-century American poetry shaped by the emergence of the figure of the poetic speaker as a default mode of reading. Now a central fiction of lyric reading, the figure of the poetic speaker developed gradually and unevenly over the course of the twentieth century. While the field of historical poetics draws attention to alternative, non-lyric modes of address, this dissertation examines how three poets writing in this period adapted the normative fiction of the poetic speaker in order to explore new modes of address. By choosing three mid-century poets who are rarely studied beside one another, this dissertation resists the aesthetic factionalism that structures most historical models of this period. My first chapter, “Robert Lowell’s Crisis of Reading: The Confessional Subject as the Culmination of the Romantic Tradition of Poetry,” examines the origins of M.L. Rosenthal’s phrase “confessional poetry” and analyzes how that the autobiographical effect of Robert Lowell’s poetry emerges from a strange, collage-like construction of multiple texts and non- autobiographical subjects. My second chapter reads Frank O’Hara’s poetry as a form of intentionally averted communication that treats the act of writing as a surrogate for the poet’s true object of desire. -

F18-Farrar-Straus-And-Giroux.Pdf

18F Macm Farrar, Straus and Giroux LEAD The Piranhas The Boy Bosses of Naples: A Novel by Roberto Saviano, translated by Antony Shugaar In Naples, there is a new kind of gang ruling the streets: the paranze, or the children's gangs, groups of teenage boys who divide their time between counting Facebook likes, playing Call of Duty on their PlayStations, and patrolling the streets armed with pistols and AK-47s, terrorizing local residents in order to mark out their Mafia bosses' territory. Roberto Saviano's The Piranhas tells the story of the rise of one such gang and its leader, Nicolas-known to his friends and enemies as the Maharajah. Nicolas's ambitions reach far beyond doing other men's bidding: he wants to be the one giving the orders, calling the shots, and ruling the city. But the violence he is accustomed to wielding and witnessing soon spirals beyond his control-with tragic consequences. "With the openhearted rashness that belongs to every true writer, Saviano returns to tell the story of the fierce and grieving heart of Naples." -Elena Farrar, Straus and Giroux Ferrante On Sale: Sep 1/18 6 x 9 • 368 pages 9780374230029 • $35.00 • CL - With dust jacket Author Bio Fiction / Literary Location: Roberto Saviano - Under police protection Notes Roberto Saviano was born in 1979 and studied philosophy at the University of Naples. Gomorrah, his first book, has won many awards, including the prestigious Viareggio Literary Award. Promotion National review attention Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator. He is the author of Coast to Coast -

Culture and Humor in Postwar American Poetry

Palacký University, Olomouc Culture and Humor in Postwar American Poetry Jiří Flajšar Olomouc 2014 Reviewers: doc. Mgr. Jakub Guziur, Ph.D. Mgr. Vladimíra Fonfárová “The research and publication of this book was in the years 2012–2014 financed by the Faculty of Arts, Palacký University, Olomouc from the Fund for the Research Advancement.” All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, now known or hereafter invented, without written permission by the copyright holder. © Jiří Flajšar, 2014 © Palacký University, Olomouc, 2014 First Edition ISBN 978-80-244-4158-0 This book is dedicated to my family. Contents Introduction 7 Crisis or Not: On the Situation of American Poetry and Its Audience 17 Humor as a Method in Postwar American Culture Poetry 33 Allen Ginsberg: Odyssey in the American Supermarket 43 Kenneth Koch: The Poet as Serious Comic 63 “Reality U.S.A.”: The Poetry of Mark Halliday 81 R.S. Gwynn: The New Formalist Shops at the Mall 107 Campbell McGrath: The Poet as a Representative Product of American Culture 127 Tony Hoagland: The Poetry of Ironic Self-Deprecation 185 Billy Collins: The Genteel Commentator 207 Culture, Identity, and Humor in Contemporary Chinese-American Poetry 215 Bibliography 227 Index 247 Introduction The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. —Walt Whitman Something we were withholding made us weak Until we found out that it was ourselves We were withholding from our land of living —Robert Frost What counted was mythology of the self, Blotched out beyond unblotching. -

Reading by David Lehman

FOR IMMEDIATE PRESS RELEASE 4-5-17 EVENTS: Poets of National Stature Reading Series presents: Leading poet David Lehman o Reading by David Lehman, author of Poems in the Manner Of… at Writer’s Block o Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook, lecture & discussion led by David Lehman. WHO: David Lehman is one of America’s leading poets using humor and everyday language to bring us great insight into the most powerful thoughts and feelings of life. He wrote an article recently regarding Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize for the Wall Street Journal and was quoted prominently on the topic in the Washington Post. David Lehman’s books include Yeshiva Boys, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters American Songs, and most recently, Poems in the Manner of.... He edits the Best American Poetry series the Oxford Book ofAmerican Poetry. As series editor, he has earned high acclaim for his pivotal role in garnering contemporary American poetry a larger audience. One of the foremost editors, literary critics, and anthologists of contemporary American literature, David Lehman is also one of our most accomplished poets. WHEN: Reading by David Lehman: Saturday, May 20, 7:00-8:30 p.m., Writer’s Block 1020 Fremont St #100, Las Vegas, NV 89101. Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook – Lecture & Discussion by David Lehman: Sunday, May 21, 3 - 4:30 p.m. Congregation Ner Tamid, Beit Tefillah (Room) 55 N Valle Verde Dr, Henderson, NV 89074. COST: Both events are free and open to the public. CONTACT: Bruce Isaacson, CC Poet Laureate 702-205-7100 or [email protected] Angela M. -

The Piranhas the Boy Bosses of Naples: a Novel Roberto Saviano; Translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar

The Piranhas The Boy Bosses of Naples: A Novel Roberto Saviano; Translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar The saga of a city under the rule of a criminal network and the Neapolitan boys who create their own gang In Naples, there is a new kind of gang ruling the streets: the paranze, or the children’s gangs, groups of teenage boys who divide their time between counting Facebook likes, playing Call of Duty on their PlayStations, and FICTION patrolling the streets armed with pistols and AK-47s, terrorizing local residents in order to mark out their Mafia bosses’ territory. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/4/2018 9780374230029 | $27.00 / $35.00 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 368 pages Roberto Saviano’s The Piranhas tells the story of the rise of one such gang Carton Qty: 20 | 9 in H | 6 in W and its leader, Nicolas—known to his friends and enemies as the Maharajah. Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: The Wylie Agency Nicolas’s ambitions reach far beyond doing other men’s bidding: he wants to Audio: FSG be the one giving the orders, calling the shots, and ruling the city. But the violence he is accustomed to wielding and witnessing soon spirals beyond MARKETING his control—with tragic consequences. National review attention Roberto Saviano was born in 1979 and studied philosophy at the University of Print features and profiles Men’s interest media outreach Naples. Gomorrah, his first book, has won many awards, including the prestigious NPR and radio interviews Viareggio Literary Award. Original author essays Author appearances Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator. -

The Best American Poetry 2009 Series Editor David Lehman 1St Edition Download Free

THE BEST AMERICAN POETRY 2009 SERIES EDITOR DAVID LEHMAN 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Wagoner | 9780743299770 | | | | | The Best American Poetry 2009 : Series Editor David Lehman Views Read Edit View history. The list doesn't have to make any sense at all. All right, I'll say weird stuff about the fifty states, just meaningless stuff, and string it all togetherthinks Bibbins's clogged brain one fall morning at the New School. Please enter a valid email address. The editor groups poems of particular styles together, and they seemed to progress from more traditional to those that have a more modern flavor. Email address. Known for his marvelous narrative skill and humane wit, David Wagoner is one of the few poets of his generation to win the universal admiration of his peers. Like, what are the things I would do if I met Moses in a laundry room in a twenty-fifth century spaceship? He has been a contributing editor at The American Scholar[35] sincewhere he acts as quiz master for the weekly column Next Line, Pleasea public poetry-writing contest, in addition to writing various articles. A smile of complicity. For years, the Best American Poetry series, edited by David Lehman, has been on a downward slope using slope in the most generous sense of the word. Lehman, David December 4, And poets in America today are defining nothing as much as they are defining poetry itself. About This Item. Join HuffPost. See our disclaimer. This is gibberish pretending to be poetry. To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. -

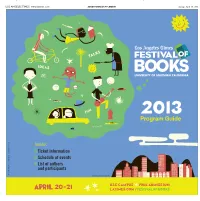

Program Guide

User: jjenisch Time: 04-09-2013 13:54 Product: LAAdTab PubDate: 04-14-2013 Zone: LA Edition: 1 Page: T1 Color: CMYK LOS ANGELES TIMES | www.latimes.com ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT Sunday, April 14, 2013 Program Guide Inside: Ticket information Schedule of events List of authors and participants Los Angeles Times Festival of Books is in association with USC. Los Angeles Times Illustration © 2013 Frank Viva User: jjenisch Time: 04-09-2013 13:54 Product: LAAdTab PubDate: 04-14-2013 Zone: LA Edition: 1 Page: T2 Color: CMYK ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT LOS ANGELES TIMES | www.latimes.com • • SUNDAY, APRIL 14, 2013 T2 User: jjenisch Time: 04-09-2013 13:54 Product: LAAdTab PubDate: 04-14-2013 Zone: LA Edition: 1 Page: T3 Color: CMYK ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT latimes.com/festivalofbooks Thank you Download the free app for iPhone and Android. Search “Festival of Books” to our Sponsors Presenting Sponsor Table of Contents 4 Welcome to the 2013 Festival of Books The Los Angeles Times Book Prizes 6 honor the best books of 2012 CENTER Major Sponsor PULLOUT Meet this year’s illustrator 9 Programming grid! Attendee tips! Kid tested, parent approved: 10 The Target Children’s Area Festival map! And more! 16 Ticket information Contributing Sponsors 18 Directions, parking and public transportation info A list of authors, entertainers and 20 Festival participants 47 Exhibitor listings Supporting Sponsors Notable book signings by authors 50 LOS ANGELES TIMES | Participating Sponsors Festival of Books Staff: www.latimes.com Ann Binney John Conroy Colleen McManus Kenneth -

Unha Introdución a the Sopranos'studies

BOLETÍN GALEGO DE LITERATURA, nº 46 / 2º SEMESTRE (2011): pp. 25-43 / ISSN 02149117 ESTUDOS Co debido respecto: / unha introdución a The Sopranos’Studies STUDIES Anxo Abuín [Recibido, xullo 2011; aceptado, outubro 2011] RESUMO A televisión estase a lexitimar como obxecto de estudo, tamén dende o ámbito da Literatura Comparada. O autor propón nes- te artigo, con certa ironía, crear unha subdisciplina académica chamada The Sopranos’Studies, que se ocupará de analizar os trazos fundamentais tanto formais coma temáticos desta serie norteamericana (HBO), convertida inmediatamente en obxecto de culto. Préstase especial atención ao concepto de flexinarrativa, que sustenta a achega aos mecanismos do relato televisivo postos en práctica por esta serie. PALABRAS CHAVE: imprevisibilidade, narración, posmodernismo, Quality TV, serialidade, Os Soprano, televisión. ABSTRACT Television is becoming a legitimate object of study in the area of 25 Comparative Literature. In this article the autor proposes, some- what ironically, the creation of an academic sub-discipline called Soprano’Studies, which would deal with both the formal and thematic aspects of this US soap opera on HBO, which rapidly became a cult series. The flexinarrative technique, which allows access to the televisual narrative mechanisms used in the series, is highlighted. KEYWORDS: entropy, narrative, postmodernism, Quality TV, series, televi- sion, The Sopranos. Poucas series mereceron tanta atención crítica como a que hoxe nos ocu- pa. Son centos as recensións que un pode atopar na internet, non sempre favorábeis, pero o certo é que tamén dende o ámbito académico Os Soprano (OS, HBO, 1999-2007) suscitou un interese extraordinario que se plasma na longa lista de artigos e monografías publicadas até a data. -

Louise Elisabeth Glück TEACHING EXPERIENCE

Louise Elisabeth Glück TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Stanford University, Stanford, California, Winter, 2011; 2013; 2014; 2018: MOHR PROFESSOR OF POETRY Stanford University, Stanford, California: VISITING PROFESSOR, CLASS FOR STEGNER FELLOWS Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts, Spring, 2008 – 2011: LECTURER, MFA PROGRAM Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, September, 2004 – : ROSENKRANZ WRITER IN RESIDENCE, ADJUNCT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, January – May, 1996: HURST PROFESSOR Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, January – May, 1995: VISITING PROFESSOR (replacing Seamus Heaney) Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September, 1984 – May, 2004 PRESTON S. PARISH ’41 THIRD CENTURY LECTURER IN ENGLISH; July, 1998 – May, 2004. Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September, 1984 – May, 2004 SENIOR LECTURER IN ENGLISH September, 1984 – June, 1998 University of California, Los Angeles, California, April 1987, 1986, 1985: REGENTS PROFESSOR Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September – December, 1983: SCOTT PROFESSOR OF POETRY University of California, Irvine, California, January – May, 1984: VISITING PROFESSOR University of California, Davis, California, January – March, 1983: VISITING PROFESSOR University of California, Berkeley, California, April, 1982: HOLLOWAY LECTURER Warren Wilson College, Swannanoa, North Carolina, 1980-1984: FACULTY AND BOARD MEMBER, M.F.A. Program for Writers Columbia University, New York, New York, January – May, 1979: VISITING PROFESSOR -

NYU Alumni Magazine Issue 10

PORTRAIT OF AN ISSUE #10 / SPRING 2008 NYC ART SCENE CHARLES SIMIC: AMERICA’S HESITANT POET LAUREATE SOLVING THE FEAR RIDDLE www.nyu.edu/alumnimagazine 0607_A012_Final_SCPSNYUMagLaPeitra.qxd 8/14/06 2:37 PM Page 1 Job: 0607_A012 Issue Date: 10/1/06 Publication: NYU Alumni Magazin Closing Date: 7/3/06 Size: 9” x 10.875” Trim Proof: Final 9.25” x 11.125” Bleed Date: 8/14/06 8.25” x 10.125” Live Designer: NMC Color(s): 4/Colors Material Type: PDF Line Screen: NA Delivery: 7/3/06 “Intellect is great. I have no compunctions about having studied it.But ultimately what’s needed here and abroad are people of good character.” —HOWARD GARDNER, EDUCATIONAL THEORIST AND VISITING PROFESSOR, DELIVERING THE INAUGURAL JACOB K. JAVITS LECTURE “FROM MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES TO FUTURE MINDS” HEARD ON CAMPUS “The number of times that “I’m not claiming for a totally my reviews made a decisive open border, I’m claiming for difference in the fortunes of an orderly flow of immigrants a movie is a very small one. to this land, for full respect of But on the other hand, it is a human and labor rights.Who very loud bullhorn that I have… would crop the vegetable if you say something mean in fields in San Joaquin Valley? The New York Times, it’s like Who would serve the hotels 100 times as mean as it was in Vegas,the restaurants here meant to have been.” in New York?” —NEW YORK TIMES CO-CHIEF FILM CRITIC A. O. SCOTT VISITING A MEDIA —VICENTE FOX QUESADA, FORMER PRESIDENT OF MEXICO, AT THE VOICES ETHICS CLASS AT THE JOURNALISM DEPARTMENT OF LATIN AMERICAN LEADERS SPEAKER