Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Official Catholic Directory® 2016, Part II

PRINT MEDIA KIT The Offi cial Catholic Directory® 2016, Part II 199 Years of Service to the Catholic Church ABOUT THE OFFICIAL CATHOLIC DIRECTORY Historically known as The Kenedy Directory, The O cial Catholic Directory is undeniably the most extensive and authoritative source of data available on the Catholic Church in the U.S. This 2-volume set is universally recognized and widely used by clergy and professionals in the Catholic Church and its institutions (parishes, schools, universities, hospitals, care centers and more). DISTRIBUTION Reservation Deadline: The O cial Catholic Directory 2016, Part II, to be published in December October 3, 2016 2016, will be sold and distributed to nearly 9,000 priests, parishes, (arch)dioceses, Materials Due: educational and other institutions, and has a reach of well over 30,000 clergy and October 10, 2016 other professionals. This includes a ‘special honorary distribution’ to members of the church hierarchy – every active Cardinal, Archbishop, Bishop and Chancery Offi ce in Publication Date: the U.S. December 2016 REACH THIS HIGHLY TARGETED AUDIENCE • Present your product or service to a highly targeted audience with purchasing power. • Reach over 30,000 Catholic clergy and professionals across the U.S. • Attain year-round access to decision makers. • Gain recognition in this highly respected publication used throughout the Catholic Church and its institutions. • Enjoy a FREE ONLINE LISTING in our Products & Services Guide with your print advertising http://www.offi cialcatholicdirectory.com/mp/index.php. • Place your advertising message directly into the hands of our readers via our outsert program. “Th e Offi cial Catholic Directory is an indispensible tool for keeping up to date with the church in the U.S. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

38 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 10|2015 MICROSTATE AND SUPERPOWER THE VATICAN IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Christian E. Rieck / Dorothee Niebuhr At the end of September, Pope Francis met with a triumphal reception in the United States. But while he performed the first canonisation on U.S. soil in Washington and celebrated mass in front of two million faithful in Philadelphia, the attention focused less on the religious aspects of the trip than on the Pope’s vis- its to the sacred halls of political power. On these occasions, the Pope acted less in the role of head of the Church, and therefore Christian E. Rieck a spiritual one, and more in the role of diplomatic actor. In New is Desk officer for York, he spoke at the United Nations Sustainable Development Development Policy th and Human Rights Summit and at the 70 General Assembly. In Washington, he was in the Department the first pope ever to give a speech at the United States Congress, of Political Dialogue which received widespread attention. This was remarkable in that and Analysis at the Konrad-Adenauer- Pope Francis himself is not without his detractors in Congress and Stiftung in Berlin he had, probably intentionally, come to the USA directly from a and member of visit to Cuba, a country that the United States has a difficult rela- its Working Group of Young Foreign tionship with. Policy Experts. Since the election of Pope Francis in 2013, the Holy See has come to play an extremely prominent role in the arena of world poli- tics. The reasons for this enhanced media visibility firstly have to do with the person, the agenda and the biography of this first non-European Pope. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

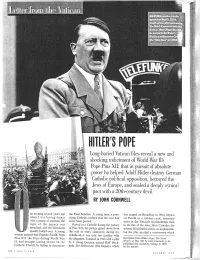

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Acta Apostolicae Sedis

ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE ANNUS XII - VOLUMEN XII ROMAE TYPIS POLYGLOTTIS VATICANIS MCMXX fr fr Num. 1 ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE ACTA BENEDICTI PP. XV CONSTITUTIO APOSTOLICA AGRENSIS ET PURUENSIS ERECTIO PRAELATURAE NULLIUS BENEDICTUS EPISCOPUS SERVUS SERVORUM DEI AD PERPETUAM REI MEMORIAM Ecclesiae universae regimen, Nobis ex alto commissum, onus Nobis imponit diligentissime curandi ut in orbe catholico circumscriptionum ecclesiasticarum numerus, ceu occasio vel necessitas postulat, augeatur, ut, coarctatis dioecesum finibus ac proinde minuto fidelium grege sin gulis Pastoribus credito, Praesules ipsi munus sibi commissum facilius ac salubrius exercere possint. Quum autem apprime constet dioecesim Amazonensem in Brasi liana Republica latissime patere, viisque quam maxime deficere, prae sertim in occidentali parte, in provinciis scilicet, quae Alto Aere et Alto Purus vocantur, ubi fideles commixti saepe saepius cum indigenis infidelibus vivunt et spiritualibus subsidiis, quibus christiana vita alitur et sustentatur, ferme ex integro carent; Nos tantae necessitati subve niendum duximus. Ideoque, collatis consiliis cum dilectis filiis Nostris S. R. E. Car dinalibus S. Congregationi Consistoriali praepositis, omnibusque mature perpensis, partem territorii dictae dioecesis Amazonensis, quod prae dictas provincias Alto Aere et Alto Purus complectitur, ab eadem dioe cesi distrahere et in Praelaturam Nullius erigere statuimus. 6 Acta Apostolicae Sedis - Commentarium Officiale Quamobrem, potestate -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

How the World Is, and Has Been Controlled by the Same Families for Millennia

How the World is, and has been controlled by the same Families for Millennia These are the Secret Elite Families that rule the world from behind the scenes and what WE can do to change society for the better Let us begin with a quick look at the current (as of May 2015) British Prime Minister David Cameron; Aristocracy and politics Cameron descends from King William IV and his mistress Dorothea Jordan through their illegitimate daughter Lady Elizabeth FitzClarence to the fifth female generation Enid Agnes Maud Levita. His father's maternal grandmother, Stephanie Levita (née Cooper) was the daughter of Sir Alfred Cooper and Lady Agnes Duff (sister of Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife) and a sister of Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich GCMG DSO PC, the Conservative statesman and author. His paternal grandmother, Enid Levita, who married secondly in 1961 a younger son of the 1st Baron Manton, was the daughter of Arthur Levita and niece of Sir Cecil Levita KCVO CBE, Chairman of London County Council in 1928. Through the Mantons, Cameron also has kinship with the 3rd Baron Hesketh KBE PC, Conservative Chief Whip in the House of Lords 1991–93. Cameron's maternal grandfather was Sir William Mount, 2nd Baronet, an army officer and the High Sheriff of Berkshire, and Cameron's maternal great-grandfather was Sir William Mount Bt CBE, Conservative MP for Newbury 1910–1922. Lady Ida Feilding, Cameron's great-great grandmother, was third daughter of William Feilding, Earl of Denbigh and Desmond GCH PC, a courtier and Gentleman of the Bedchamber. -

Annuntio Vobis Gaudium Magnum; Habemus Papam: Eminentissimum

overcome the consequences of the conflicts from the turn of 1980s and Annuntio vobis gaudium magnum; 1990s". habemus Papam: The issue of the Ukrainian Catholic Church is at the core of the "conflicts" Eminentissimum ac Reverendissimum Dominum, to which Hilarion was referring. Although it was unbanned following the Dominum Georgium Marium collapse of the Soviet Union, it was left without its original churches, which had been seized by the Communists under Soviet rule and later Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Cardinalem Bergoglio transferred to the Orthodox Church. qui sibi nomen imposuit Franciscum. Still, "on several occasions, Pope Francis has shown spiritual sympathy towards the Orthodox Church and a desire for closer contacts," Hilarion Statement on our new Pope from Metropolitan William said. It is his hope that under the new pontificate "relations of alliance will develop and that our ties will be strengthened." Congratulations to our newly-elected Pope Francis I. The first modern-day Pope born outside of Europe, the first Jesuit, and the first to be named after Saint Francis, Pope Francis has been very supportive of the Eastern Catholic Churches in Latin America during his tenure as Archbishop of Buenos Aires in his native Argentina. For this, we are especially thankful. Bishop Gerald Dino of Phoenix and I are in Rome and will represent our Byzantine Catholic Metropolitan Church at his enthronement at Saint Peter's Basilica on Tuesday, March 19. You can already feel the joy, hope and excitement for the future. As we begin to remember his name in the litanies of the Divine Liturgy and in our daily prayer, we ask that our new Pope receives strength from the Father and wisdom from the Holy Spirit. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Refugee Policies from 1933 Until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities

Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities ihra_4_fahnen.indd 1 12.02.2018 15:59:41 IHRA series, vol. 4 ihra_4_fahnen.indd 2 12.02.2018 15:59:41 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (Ed.) Refugee Policies from 1933 until Today: Challenges and Responsibilities Edited by Steven T. Katz and Juliane Wetzel ihra_4_fahnen.indd 3 12.02.2018 15:59:42 With warm thanks to Toby Axelrod for her thorough and thoughtful proofreading of this publication, to the Ambassador Liviu-Petru Zăpirțan and sta of the Romanian Embassy to the Holy See—particularly Adina Lowin—without whom the conference would not have been possible, and to Katya Andrusz, Communications Coordinator at the Director’s Oce of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. ISBN: 978-3-86331-392-0 © 2018 Metropol Verlag + IHRA Ansbacher Straße 70 10777 Berlin www.metropol-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Druck: buchdruckerei.de, Berlin ihra_4_fahnen.indd 4 12.02.2018 15:59:42 Content Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust ........................................... 9 About the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) .................................................... 11 Preface .................................................... 13 Steven T. Katz, Advisor to the IHRA (2010–2017) Foreword The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the Holy See and the International Conference on Refugee Policies ... 23 omas Michael Baier/Veerle Vanden Daelen Opening Remarks ......................................... 31 Mihnea Constantinescu, IHRA Chair 2016 Opening Remarks ......................................... 35 Paul R. Gallagher Keynote Refugee Policies: Challenges and Responsibilities ........... 41 Silvano M. Tomasi FROM THE 1930s TO 1945 Wolf Kaiser Introduction ............................................... 49 Susanne Heim The Attitude of the US and Europe to the Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany ....................................... -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet.