Do You Remember

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Infrastructure Capacity Report.Pdf

Social Infrastructure Capacity Report For a Proposed Strategic Housing Development At Belmayne P4, Belmayne, Dublin 13 Prepared by McGill Planning Ltd On behalf of Balgriffin Park Limited April 2021 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Site Context ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Proposed Development .......................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Demographics ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Planning Policy Context .......................................................................................................................... 8 Open Space and Sport ............................................................................................................................. 9 Education .............................................................................................................................................. 11 Childcare Facilites ................................................................................................................................ -

North Central Area Committee Agenda for September

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY MEETING OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE NORTHSIDE CIVIC CENTRE, BUNRATTY ROAD COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17 ON MONDAY 17th SEPTEMBER 2012 AT 2.00 P.M TO EACH MEMBER OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE You are hereby notified to attend the monthly meeting of the above Committee to be held in the Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 on 17th September 2012 at 2.00 pm to deal with the items on the agenda attached herewith. DAVE DINNIGAN AREA MANAGER Dated this the 11th September 2012 Contact Person: Ms. Dympna McCann, Ms. Yvonne Kirwan, Phone: 8166712 Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Fax: 8775851 EMAIL: [email protected] 1 Item Page Time 4467. Minutes of meeting held on the 16th July 2012 7-9 4468. Questions to Area Manager 60-68 4469. Area Matters 1hr 30mins a. Presentation from Raheny Barry Murphy/Con Clarke b. Presentation on Sutton to Sandycove Cycleway ( Con Kehely ) c. Update on North City Arterial Watermain at Clontarf/ 10-18 Hollybrook Road ( Adrian Conway ) d. Verbal update on Dublin Waste Water Treatment plant proposals.Pat Cronin e. Barnmore ( Marian Dowling ) North Central Area to write to Fingal councillors raising their concerns re Barnmore. Councillor Paddy Bourke to raise the issue of Barnmore at Regional Authority meeting on 17/7/2012. Clarify the actions open to FCC on foot of any enforcement notices being served and the likely date for the Supreme Court hearing Clarify on legal actions open to DCC on matter of permit Follow up on the carrying out of air quality and noise surveys f. -

Cycle Network Plan Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan

Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan Draft Greater Dublin Area Cycle Network Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: WRITTEN STATEMENT 3.8. Dublin South East Sector ................................................................................................ 44 INTRODUCTION 3.8.1 Dublin South East - Proposed Cycle Route Network........................................................... 44 CHAPTER 1 EXISTING CYCLE ROUTE NETWORK ....................................................... 1 3.8.2 Dublin South East - Proposals for Cycle Route Network Additions and Improvements...... 44 3.8.3 Dublin South East - Existing Quality of Service ................................................................... 45 1.1. Quality of Service Assessments ........................................................................................1 CHAPTER 4 GDA HINTERLAND CYCLE NETWORK ................................................... 46 1.2. Existing Cycling Facilities in the Dublin City Council Area..................................................1 4.1 Fingal County Cycle Route Network................................................................................ 46 1.3. Existing Cycling Facilities in South Dublin County Area.....................................................3 4.1.1 South Fingal Sector.............................................................................................................. 46 1.4. Existing Cycling Facilities in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown Area .............................................5 4.1.2 Central Fingal Sector -

Notification to Attend Monthly Meeting of the North Central Area Committee

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY MEETING OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE NORTHSIDE CIVIC CENTRE, BUNRATTY ROAD COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17 ON MONDAY 20th JULY 2015 AT 2.00 P.M TO EACH MEMBER OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE You are hereby notified to attend the monthly meeting of the above Committee to be held on 20th July 2015 at 2.00 pm in Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 to deal with the items on the agenda attached herewith. DAVE DINNIGAN AREA MANAGER Dated this day, 14th July 2015. Contact Person: Ms. Dympna McCann, Phone: 2228847 Ms. Yvonne Kirwan, Phone: 2228848 Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Fax: 8775851 EMAIL: [email protected] Page 1 of 183 Page Time 4937. Election of Chairperson 4938. Election of Vice Chairperson 4939. Minutes of meeting held on the 15th June 2015,30th June 2015 6-10 4940. Questions to Area Manager 58-66 4941. Area Matters 1 hour a. Clontarf to Amiens Street Cycle Route Tony Mc Gee b. Programme for Life Noel Kelly c. Housing Allocations ( Report herewith) Mary Flynn, Dave Keating 11-22 d. Cromcastle Court Heating ( Report to follow) e. Pre-Part 8 Notification for information purposes only – 23 Construction of Changing Rooms in Springdale Park, Raheny, Dublin 5 ( Report herewith) Bernard Brady, Eoin Ward f. Naming & Numbering Proposal for development on a site at 1-12 Castle 24 Vernon, Dollymount Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3.( Report herewith) Elaine Mulvenny g. Public Domain Report (Report herewith) –(Richard Cleary) 25-26 4942. -

Belcamp-Brochure-Jan.Pdf

E ST. 1793 HOMES BUILT WITH THEIR FOUNDATIONS Welcome to Belcamp, an outstanding IN HISTORY new development of spacious family homes on a historical site just off the prestigious Malahide Road in Dublin. Belcamp is a wonderful addition to this thriving neighbourhood, offering a great standard of living convenient to every amenity a growing family could want. CREATING A NEW CHAPTER IN The Story of Belcamp STANDING ON THE Belcamp brings together the practical needs of modern families with the traditional details of its historic buildings in a sympathetic and attractive design. A long grand avenue leads to the listed buildings, while a series of small roads and cul-de-sacs set off the avenue contain a variety of elegant concrete-built houses, traditional but classic in style with extensive use of red brick. Washington Avenue leads from the avenue to Shoulders of the old Washington Monument, overlooking a linear green area by the stream. Inscription on The Washington Monument at GIANTS Belcamp . “Oh, ill-fated Britain! The folly of Lexington and Concord will rend asunder and THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT MONUMENT THE WASHINGTON THE LAKE & THE LAKE & The homes at Belcamp are built in the The Belcamp estate was purchased by forever disjoin America from thy empire” grounds of the old Belcamp Hall, the the Oblate brothers in 1884. In 1903, the design of which was attributed to James brothers built a redbrick Gothic Revival- Hoban (who later designed The White style chapel, designed by architect George ARCHITECT 1755–1831 House in Washington DC) in 1763 for Coppinger Ashlin and containing stained JAMES HOBAN Sir Edward Newenham (1734-1814), an glass windows by the famous artist Harry MP and a colonel in the Irish Volunteers. -

Agenda Document for Arts, Culture and Recreation SPC, 13/11/2017 09:30

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MEETING OF THE ARTS, CULTURE AND RECREATION SPC TO BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, CITY HALL, DAME STREET, DUBLIN 2. ON MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 AT 9.30 AM AGENDA MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 PAGE 1 Minutes of meeting held on 11th September 2017 3 - 6 2 Presentation on the UNESCO City of Literature - Alison Lyons, Director of Dublin 7 - 16 UNESCO City of Literature 3 Presentation on the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane Draft Strategic Plan 2018 17 - 40 - 2023 - Barbara Dawson, Director a) Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane Draft Strategic Plan 2018 - 2023 41 - 52 4 Report of the Chief Executive, Owen Keegan, on the establishment of a Dublin 53 - 56 City Council Cultural Company - Ray Yeates, City Arts Officer 5 Review of the Passport for Leisure and Over 65's Scheme - Jim Beggan, Senior 57 - 62 Executive Officer 6 Report on George Bernard Shaw House - Brendan Teeling, Deputy City Librarian 63 - 64 7 Report on the Implementation of the Cultural Strategy - Arts Education and 65 - 68 Learning - Ray Yeates, City Arts Officer 8 Verbal update on the New City Library at Parnell Square - Margaret Hayes, Dublin City Librarian 9 Management Update 69 - 108 10 Proposed Dates for the Arts, Culture and Recreation SPC 2018 meetings 109 - 110 11 Approved Minutes of Dublin City Sports and Wellbeing Partnership Advisory 111 - Board meeting held 15th May 2017 114 12 Approved Minutes of the Commemorations Sub-Committe meeting held 17th May 115 - 2017 116 13 Approved Minutes of the Commemorative Naming Committee meeting held 17th 117 - May -

1 Notification to Attend Monthly Meeting of The

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY MEETING OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE NORTHSIDE CIVIC CENTRE, BUNRATTY ROAD COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17 ON MONDAY 18th MAY 2015 AT 2.00 P.M TO EACH MEMBER OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE You are hereby notified to attend the monthly meeting of the above Committee to be held on 18TH May 2015 at 2.00 pm in Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 to deal with the items on the agenda attached herewith. DAVE DINNIGAN AREA MANAGER Dated this the 12th May 2015 Contact Person: Ms. Dympna McCann, Phone: 2228847 Ms. Yvonne Kirwan, Phone: 2228848 Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Fax: 8775851 EMAIL: [email protected] 1 Items Page Time 4911. Minutes of meeting held on the 20th April 2015 6-8 5 mins 4912. Questions to Area Manager 55-61 4913. Area Matters 55 mins a. Representative from Iarnrod Eireann b. S to S Chris Manzira, Roughan 0’Donovan Consultant Engineers c. Fairview Village Public Realm Proposals ( Report herewith) 9 d. Update on all existing projects that received Sports Capital funding ( Report to follow ) e. Naming & Numbering Proposal for development on a site at 1A Clonturk 10 -11 Park, Drumcondra, Dublin 9 – (Report herewith) – Elaine Mulvenny f. Naming & Numbering Proposal for development on a site at the entrance 12 into Castleview, Artane, Dublin 5 ( Report herewith) Elaine Mulvenny g. Grant of a 4-year licence to operate a tearoom in the Red Stables, St. Anne’s Park, Mount Prospect Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3 to Olive’s Room 13-16 Ltd (Moloughney’s), 35 Kincora Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3. -

GDD Community Benefits Scheme

June 2018 Greater Dublin Drainage Community Benefits Scheme 1 | Irish Water | [Type Document Title] IW/FF/LDB/0115 Greater Dublin Drainage - Community Benefits Scheme Overview Irish Water is the national utility responsible for the delivery of Ireland’s water and wastewater infrastructure and services. Corporate responsibility is an important part of how we deliver our business. Our corporate responsibility initiatives underpin our commitment to enhancing the health and quality of life of the people of Ireland, protecting our environment and enabling economic and social development. If planning permission is granted, the Greater Dublin Drainage project will be the largest wastewater treatment advancement in Ireland for many years. Once operational from 2026, the GDD project will have the capacity to provide long- term wastewater treatment for the equivalent of half a million people in the Greater Dublin Area (GDA). The delivery of the GDD project is a key strategic investment priority under the National Planning Framework (Project Ireland 2040), the National Development Plan 2018-2027, Regional Planning Guidelines, and the Fingal Development Plan 2017-2023. The GDD project will underpin the sustainable growth of the Dublin region to 2050 forming a vital part of the primary infrastructure network that is essential to enable residential, commercial and public development. The project will bring significant, lasting benefits for the environment, for public health and for the economic and social growth through providing the wastewater treatment capacity that the region needs to support its growth. GDD will protect and enhance Dublin’s water quality for all. The project is necessary to achieve compliance with the Water Framework Directive, the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive and other relevant EU and national regulations related to water quality. -

Notification to Attend Monthly Meeting of the North Central Area

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY MEETING OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE NORTHSIDE CIVIC CENTRE, BUNRATTY ROAD, COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17, ON MONDAY 16 TH MAY 2011 AT 2.00 P.M TO EACH MEMBER OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE You are hereby notified to attend the monthly meeting of the above Committee to be held in the Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 , on 16 th May, 2011 at 2.00 p.m. to deal with the items on the agenda attached herewith. CÉLINE REILLY AREA MANAGER Dated this the 10th May 2011 Contact Person: Ms. Dympna McCann, Ms. Yvonne Kirwan, Phone: 8166712 Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Fax: 8775851 EMAIL: [email protected] 1 Item Page Time 4210. Minutes of meeting held on the 18 th April 2011 6-10 5 mins 4211. Questions to Area Manager 35-41 4212. Area Matters 1hr a. Representative from Dublin Bus --- Donal Keating b. Travellers Newtown Court ( Report herewith ) - Kieran 11 Cunningham c. Report on Traffic Management N32, Clare Hall, North Fringe 12 (Report herewith) Ronan O’Dea d. Report on Barnmore Construction ( Report herewith ) John 13 Bruckshaw e. Motion 4050 – September 2010. a. Motion in the name of Councillor Damian O’Farrell This Area Committee agrees to honour the memory of the late Sean Dublin Bay Loftus former Lord Mayor of Dublin. In agreement with Mr Loftus’s family and the Local Area Committee a suitable significant memorial will be decided upon. E.g. An existing walkway / promenade in his name. -

Manager's Report Volume 2

e Manager’s Report Draft Dublin City Development Plan 2011 - 2017 Volume 2 May 2010 MANAGER’S REPORT Draft Dublin City Development Plan 2011-2017 Table of Contents CHAPTER PAGE PART 1 – INTRODUCTION 5 PART 2 - SUBMISSION BY MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, HERITAGE & LOCAL GOVERNMENT & MANAGER’S RESPONSE AND RECOMMENDATIONS 11 PART 3 - SUMMARY OF SUBMISSIONS AND MANAGER’S RESPONSE AND RECOMMENDATIONS 17 1 BACKGROUND TO MAKING THE PLAN 19 2 CONTEXT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 23 3 DEVELOPMENT PLAN STRATEGY TO 2017 27 4 SHAPING THE CITY 49 5 CONNECTING AND SUSTAINING THE CITY’S INFRASTRUCTURE 57 6 GREENING THE CITY 91 7 FOSTERING DUBLIN’S CHARACTER AND CULTURE 105 8 MAKING DUBLIN THE HEART OF THE REGION 133 9 REVITALISING THE CITY’S ECONOMY 137 10 STRENGTHENING THE CITY AS THE NATIONAL RETAIL DESTINATION 151 11 PROVIDING QUALITY HOMES IN A COMPACT CITY 161 12 CREATING GOOD NEIGHBOURHOODS AND SUCCESSFUL COMMUNITIES 171 13 IMPLEMENTATION 179 14 DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT 183 15 LAND USE ZONING (including Site Specific Zoning submissions) 189 16 GUIDING PRINCIPLES 341 17 DEVELOPMENT STANDARDS 347 APPENDIX PAGE 2. National, Regional and Local Strategies 381 3. The Housing Strategy 382 4. The Retail Strategy 383 5. Travel Plans 386 6. Transport Assessment 387 7. Strategic Cycle Network 388 8. Road Standards for Various Classes of Development 389 11. Proposed Architectural Conservation Areas (ACAs) 390 12. Stone Setts to Be Retained Restored or Introduced 392 13. Paved Areas and Streets with Granite Kerbing 393 14. Guidelines for Waste Storage Facilities 394 15. Flood Defence Infrastructure 395 16. Guidelines for Telecommunications Antennae 396 17. -

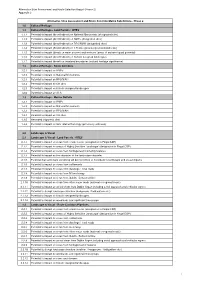

Appendix 3: List of Sub-Criteria

Alternative Sites Assessment and Route Selection Report (Phase 2) Appendix 3 Alternative Sites Assessment and Route Selection Matrix Sub-Criteria - Phase 2 1.0 Cultural Heritage 1.1 Cultural Heritage - Land Parcels / SITES 1.1.1 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on National Monuments (designated sites) 1.1.2 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on RMPs (designated sites) 1.1.3 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on RPS/NIAH (designated sites) 1.1.4 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on CH sites (previously unrecorded sites) 1.1.5 Potential to impact (direct) on water courses and environs (areas of archaeological potential) 1.1.6 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on historic designed landscapes 1.1.7 Potential to impact (direct) on townland boundaries (cultural heritage significance) 1.2 Cultural Heritage - Route Corridors 1.2.1 Potential to impact on RMPs 1.2.2 Potential to impact on National Monuments 1.2.3 Potential to impact on RPS/NIAH 1.2.4 Potential to impact on CH sites 1.2.5 Potential to impact on historic designed landscapes 1.2.6 Potential to impact on ACA 1.3 Cultural Heritage - Marine Outfalls 1.3.1 Potential to impact on RMPs 1.3.2 Potential to impact on National Monuments 1.3.3 Potential to impact on RPS/NIAH 1.3.4 Potential to impact on CH sites 1.3.5 Recorded shipwreck sites 1.3.6 Potential to impact on inter-tidal archaeology (previously unknown) 2.0 Landscape & Visual 2.1 Landscape & Visual - Land Parcels / SITES 2.1.1 Potential to impact on views from scenic routes (designation in Fingal CDP) 2.1.2 Potential -

Download Public Spending Code Report 2017 Detailed Inventory

Expenditure being considered Expenditure being incurred Expenditure recently ended Notes Current Capital > €0.5m > €0.5m Carlow County Council > €0.5m Capital Grant Schemes > Capital Projects Current Expenditure Capital Grant Schemes Capital Projects Current Expenditure Capital Grant Schemes Capital Projects €0.5m €0.5 - €5m €5 - €20m €20m plus Housing & Building A01 Maintenance/Improvement LA Housing €2,050,340 A03 Housing Rent and Tenant Purchase Administration €277,260 A06 Support to Housing Capital Programme €1,496,183 A07 RAS and Leasing Programme €5,656,316 16 Houses at Ard na Greine, Tullow (St Patricks Park) €2,000,000 2 Houses at Bilboa €315,000 26 Houses at Sleatty Street, Graiguecullen (CALF CLUID) €3,800,000 10 Houses at Rivercourt, Carlow (CALF CLUID) €1,900,000 4 Houses, Slate Row, Hacketstown €621,000 5 Houses, The Laurels, Carlow €430,000 1 house at Drummond, Carlow €140,000 Part V - Castleoaks (BRENCO) €700,000 4 houses at St Olivers Cresent, Myshall €650,000 4 houses at Mount Leinster Park, Carlow €547,000 4 houses at Pound Lane Borris €500,000 4 houses at St Olivers Park, Myshall €641,000 10 Houses Rathvilly €1,521,835 24 Houses Bagenalstown €3,370,828 5 Apartments, Maryborough Street, Graiguecullen €990,000 1 Rural Dwelling at Paulville, Tullow, Co Carlow €135,000 10 Houses at Barrett Street, Bagenalstown €1,400,000 4 Houses, Myshall, Co Carlow €510,000 21 Houses Dublin Road, Carlow €2,800,000 8 Houses Rathvilly, Co Carlow €1,200,000 42 Houses Bagenalstown Co Carlow €7,000,000 4 Apartments Main Street Borris Co Carlow