Al-Biruni, Muhammad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al-Biruni: a Great Muslim Scientist, Philosopher and Historian (973 – 1050 Ad)

Al-Biruni: A Great Muslim Scientist, Philosopher and Historian (973 – 1050 Ad) Riaz Ahmad Abu Raihan Muhammad bin Ahmad, Al-Biruni was born in the suburb of Kath, capital of Khwarizmi (the region of the Amu Darya delta) Kingdom, in the territory of modern Khiva, on 4 September 973 AD.1 He learnt astronomy and mathematics from his teacher Abu Nasr Mansur, a member of the family then ruling at Kath. Al-Biruni made several observations with a meridian ring at Kath in his youth. In 995 Jurjani ruler attacked Kath and drove Al-Biruni into exile in Ray in Iran where he remained for some time and exchanged his observations with Al- Khujandi, famous astronomer which he later discussed in his work Tahdid. In 997 Al-Biruni returned to Kath, where he observed a lunar eclipse that Abu al-Wafa observed in Baghdad, on the basis of which he observed time difference between Kath and Baghdad. In the next few years he visited the Samanid court at Bukhara and Ispahan of Gilan and collected a lot of information for his research work. In 1004 he was back with Jurjania ruler and served as a chief diplomat and a spokesman of the court of Khwarism. But in Spring and Summer of 1017 when Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna conquered Khiva he brought Al-Biruni, along with a host of other scholars and philosophers, to Ghazna. Al-Biruni was then sent to the region near Kabul where he established his observatory.2 Later he was deputed to the study of religion and people of Kabul, Peshawar, and Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and other areas of Pakistan and India under the protection of an army regiment. -

The History of Arabic Sciences: a Selected Bibliography

THE HISTORY OF ARABIC SCIENCES: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Mohamed ABATTOUY Fez University Max Planck Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin A first version of this bibliography was presented to the Group Frühe Neuzeit (Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin) in April 1996. I revised and expanded it during a stay of research in MPIWG during the summer 1996 and in Fez (november 1996). During the Workshop Experience and Knowledge Structures in Arabic and Latin Sciences, held in the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin on December 16-17, 1996, a limited number of copies of the present Bibliography was already distributed. Finally, I express my gratitude to Paul Weinig (Berlin) for valuable advice and for proofreading. PREFACE The principal sources for the history of Arabic and Islamic sciences are of course original works written mainly in Arabic between the VIIIth and the XVIth centuries, for the most part. A great part of this scientific material is still in original manuscripts, but many texts had been edited since the XIXth century, and in many cases translated to European languages. In the case of sciences as astronomy and mechanics, instruments and mechanical devices still extant and preserved in museums throughout the world bring important informations. A total of several thousands of mathematical, astronomical, physical, alchemical, biologico-medical manuscripts survived. They are written mainly in Arabic, but some are in Persian and Turkish. The main libraries in which they are preserved are those in the Arabic World: Cairo, Damascus, Tunis, Algiers, Rabat ... as well as in private collections. Beside this material in the Arabic countries, the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, the Biblioteca del Escorial near Madrid, the British Museum and the Bodleian Library in England, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the Süleymaniye and Topkapi Libraries in Istanbul, the National Libraries in Iran, India, Pakistan.. -

The Importance of Translation Mathematics Old Script ABSTRACT

Malaysian Journal of Mathematical Sciences 3(1): 55-66 (2009) The Importance of Translation Mathematics Old Script 1Shahrul Nizam Ishak, 2Noor Hayati Marzuki, 3Jamaludin Md. Ali School of Mathematical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper, a concise discussion of the text study will be carried out by focusing on the significant of Malay mathematics old script translation. We also discuss the importance of the translation work that need to emphasize. Stages of the translation period based on history knowledge also been highlighted. An example of the translation from Rau ḍat al-Ḥuss āb f ī ‘Ilm al-Ḥis āb that was written by Malay ‘Ulama 1 in 1307H/1893M is also shown here. The book was printed in Egypt and has been used in teaching and learning among the student at the Holy Mosque ( Masjid al- Har ām). Therefore, from this work hope that the introduction of the book presented here is sufficient to stimulate interest in readers and researchers to embark and investigate the beauty and the power of script translation in providing more knowledge especially in the mathematics education area. Keywords: Mathematics Translation, Old Script, Rau ḍat al-Ḥuss āb. INTRODUCTION The amount of translation into Arabic from Greek, Syrian, Persian and Sanskrit was at its peak during the ninth and tenth century. ‘Ulama of Islam, Christianity, Judaism and even Zoroastrianism were employed in the translation and writing new scientific masterpieces. In the course of time the works of Euclid, Ptolemy, Aristotle, Apollonius, Archimedes, Heron, Diophantus and the Hindus were accessible in Arabic. -

By Sean Jenkins

Web-Based Homework versus Paper-Based Homework in United Arab Emirates Secondary Mathematics By Sean Jenkins A Dissertation Submitted in Fulfilment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (Mathematics Education) Of University College London Institute of Education Department of Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment University College London March 05, 2021 Abstract This study investigated whether Web-based homework (WBH) in mathematics is a method of homework delivery more suitable than traditional paper-based homework (PBH) for United Arab Emirates (UAE) secondary students in Abu Dhabi. Few studies have addressed delivery methods for mathematics homework outside of a context where homework is considered usual practice. The study centres in the UAE because of its culturally distinctive attitudes towards homework completion and reportedly low levels of self-efficacy among Emirate students. If homework completion and performance were to increase, WBH could offer opportunities to enrich student learning and engagement in mathematics. This study used the WBH tools Myimaths and GeoGebra in selected school years. The research questions for this study were as follows: (1) Do students interact more with WBH than with PBH? (2) What are student perceptions of their learning with WBH and PBH? The sample consisted of approximately 2,000 students. The data for this two-group, pre-and post-test control group design was collected over three years, covering school years 2012 to 2015. As a measure of interaction, a Pearson Chi-square test suggested that student homework completion was significantly higher in the WBH group. The result led to the rejection of the null hypothesis for the first research question, suggesting that students do interact more with WBH than with PBH. -

Dramatis Personae •

Dramatis Personae • Note: all dates are approximate. ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356– 323 bc). Macedonian ruler who, af- ter invading Central Asia in 329 bc, spent three years in the region, establishing or renaming nine cities and leaving behind the Bactrian Greek state, headquartered at Balkh, which eventually ruled territo- ries extending into India. Awhad al- Din ANVARI (1126– 1189). Poet and boon companion of Sultan Sanjar at Merv who, boasting of his vast knowledge, wrote that, “If you don’t believe me, come and test me. I am ready.” Nizami ARUDI. Twelfth- century Samarkand- born poet and courtier of the rulers of Khwarazm and of Ghor, and author of Four Discourses, in which he argued that a good ruler’s intellectual stable should include secretaries, poets, astrologers, and physicians. Abu Mansur Ali ASADI. Eleventh- century poet from Tus and follower of Ferdowsi. Working at a court in Azerbaijan, Asadi versified The Epic of Garshasp (Garshaspnameh), which ranks second only to Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh among Persian epic poems. Farid al- Din ATTAR (1145– 1221). Pharmacist and Sufi poet from Nishapur, who combined mysticism with the magic of the story- teller’s art. His Conference of the Birds is an allegory in which the birds of the world take wing in search of Truth, only to find it within themselves. Yusuf BALASAGUNI (Yusuf of Balasagun). Author in 1069 of the Wisdom of Royal Glory, a guide for rulers and an essay on ethics. Written in a Turkic dialect, Yusuf’s volume for the first time brought a Turkic language into the mainstream of Mediterranean civilization and thought. -

The Islamic Connection

THE ISLAMIC CONNECTION CONTRIBUTIONS MADE BY THE ARABS TO MATHEMATICS by John E. Sasser, Ph.D. COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2007 by John E. Sasser. All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. 2 The Arab Contribution to Mathematics CONTENTS Foreword...............................................……............... 4 Dedication..................................................…….......... 5 Preface........................................................…….......... 7 Map............................................................…….......... 9 List of Illustrations…………………………………... 10 Introduction..................................................……........ 11 The Search for Knowledge.....................…................. 23 Antiquity and the European Renaissance: Translations. Geometry: Geometric Constructions……………….. Trigonometry Direction Time NumberTheory: ……………………………………. The Hindu-Arabic Numeration System. Astronomy and the Calendar: Algebra: Conclusion..........................................……................. References........................................……................... Glossary……………………………………………... Index......................................................…….............. 3 The Arab Contribution to Mathematics FOREWORD This paper describes selected principal contributions to mathematics and the Arabs. Selection of appropriate examples to illustrate -

History of Islamic Science

History of Islamic Science George Sarton‟s Tribute to Muslim Scientists in the “Introduction to the History of Science,” ”It will suffice here to evoke a few glorious names without contemporary equivalents in the West: Jabir ibn Haiyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Fargani, Al-Razi, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Battani, Hunain ibn Ishaq, al-Farabi, Ibrahim ibn Sinan, al-Masudi, al-Tabari, Abul Wafa, ‘Ali ibn Abbas, Abul Qasim, Ibn al-Jazzar, al-Biruni, Ibn Sina, Ibn Yunus, al-Kashi, Ibn al-Haitham, ‘Ali Ibn ‘Isa al- Ghazali, al-zarqab,Omar Khayyam. A magnificent array of names which it would not be difficult to extend. If anyone tells you that the Middle Ages were scientifically sterile, just quote these men to him, all of whom flourished within a short period, 750 to 1100 A.D.” Preface On 8 June, A.D. 632, the Prophet Mohammed (Peace and Prayers be upon Him) died, having accomplished the marvelous task of uniting the tribes of Arabia into a homogeneous and powerful nation. In the interval, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, the whole North Africa, Gibraltar and Spain had been submitted to the Islamic State, and a new civilization had been established. The Arabs quickly assimilated the culture and knowledge of the peoples they ruled, while the latter in turn - Persians, Syrians, Copts, Berbers, and others - adopted the Arabic language. The nationality of the Muslim thus became submerged, and the term Arab acquired a linguistic sense rather than a strictly ethnological one. As soon as Islamic state had been established, the Arabs began to encourage learning of all kinds. -

![Astronomers and Astrologers[Edit] Main Article: List of Muslim Astronomers Sind Ibn Ali (-864) Ali Qushji (1403-1474) Ahmad Khan](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0228/astronomers-and-astrologers-edit-main-article-list-of-muslim-astronomers-sind-ibn-ali-864-ali-qushji-1403-1474-ahmad-khan-3480228.webp)

Astronomers and Astrologers[Edit] Main Article: List of Muslim Astronomers Sind Ibn Ali (-864) Ali Qushji (1403-1474) Ahmad Khan

Astronomers and astrologers[edit] Main article: List of Muslim astronomers Sind ibn Ali (-864) Ali Qushji (1403-1474) Ahmad Khani (1650-1707) Ibrahim al-Fazari (-777) Muhammad al-Fazari (-796 or 806) Al-Khwarizmi, Mathematician (780-850 CE) Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (Albumasar) (787-886 CE) Al-Farghani (800/805-870) Banū Mūsā (Ben Mousa) (9th century) Dīnawarī (815-896) Al-Majriti (d. 1008 or 1007 CE) Al-Battani (858-929 CE) (Albatenius) Al-Farabi (872-950 CE) (Abunaser) Abd Al-Rahman Al Sufi (903-986) Abu Sa'id Gorgani (9th century) Kushyar ibn Labban (971-1029) Abū Ja'far al-Khāzin (900-971) Al-Mahani (8th century) Al-Marwazi (9th century) Al-Nayrizi (865-922) Al-Saghani (-990) Al-Farghani (9th century) Abu Nasr Mansur (970-1036) Abū Sahl al-Qūhī (10th century) (Kuhi) Abu-Mahmud al-Khujandi (940-1000) Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī (940-998) Ibn Yunus (950-1009) Ibn al-Haytham (965-1040) (Alhacen) Bīrūnī (973-1048) Avicenna (980-1037) (Ibn Sīnā) Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī (1029-1087) (Arzachel) Omar Khayyám (1048-1131) Al-Khazini (fl. 1115-1130) Ibn Bajjah (1095-1138) (Avempace) Ibn Tufail (1105-1185) (Abubacer) Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi (-1204) (Alpetragius) Averroes (1126-1198) Al-Jazari (1136-1206) Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī (1135-1213) Anvari (1126-1189) Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (-1266) Nasir al-Din Tusi (1201-1274) Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236-1311) Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī (1250-1310) Ibn al-Shatir (1304-1375) Shams al-Dīn Abū Abd Allāh al-Khalīlī (1320-80) Jamshīd al-Kāshī (1380-1429) Ulugh Beg (1394-1449) Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf (1526-1585) -

Inventory of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Library of the University of Leiden

INVENTORIES OF COLLECTIONS OF ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS INVENTORY OF THE ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LEIDEN VOLUME 2 MANUSCRIPTS OR. 1001 – OR. 2000 REGISTERED IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY IN THE PERIOD BETWEEN 1665 AND 1871 COMPILED BY JAN JUST WITKAM PROFESSOR OF PALEOGRAPHY AND CODICOLOGY OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY INTERPRES LEGATI WARNERIANI TER LUGT PRESS LEIDEN 2007 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007. The form and contents of the present inventory are protected by Dutch and international copyright law and database legislation. All use other than within the framework of the law is forbidden and liable to prosecution. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First electronic publication: 27 October 2006. Latest update: 13 August 2007 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007 2 PREFACE The arrangement of the present volume of the Inventories of Oriental manuscripts in Leiden University Library does not differ in any specific way from the volumes which have been published earlier. For the sake of brevity I refer to my prefaces in those volumes. A few essentials my be repeated here. Not all manuscripts mentioned in the present volume were viewed by autopsy, but many were. The sheer number of manuscripts makes this impossible. At a later stage this may be achieved, but trying to achieve this at the present stage of inventorizing would seriously hamper the progress of the present project. -

846-856 Research Article Different Approaches to Studying the Natural-Scientific and Historical-Philosophical Heritage of the Khorezm Academy of Ma’Mun

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No.11 (2021), 846-856 Research Article Different Approaches To Studying The Natural-Scientific And Historical-Philosophical Heritage Of The Khorezm Academy Of Ma’mun Masharipova Gularam Kamilovna1 1Professor of the Tashkent Institute of Textile and Light Industry Article History: Received: 11 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 10 May 2021 Abstract: The article scientifically analyzes the rich natural science heritage and socio-philosophical views of the scientists of the Khorezm Academy of Ma’mun. The rich scientific research and socio-philosophical views of Abu Raikhan al-Biruni, Abu Nasr ibn Iraq and Abu Ali ibn Sina in the field of exact and philosophical sciences, characteristic of this period, are studied. based on exhaustive sources. Keywords: exact and philosophical sciences, mathematics, astronomy, philosophical views, world, man, values, social relations, Renaissance, science, fundamental research. 1. Relevance of the topic Eastern sources, including works written in the field of philosophical sciences in Khorezm in the X-XII centuries and which have come down to us, served as an important source, on the other hand, materials of archaeological research were used as material. Speaking about the origins of the development of philosophical sciences in Khorezm in the X-XII centuries, it should be noted that there is a tradition of continuity in science and the influence of ancient Greek science. The achievements of ancient Greek science were introduced in Khorezm in the X-XII centuries in two ways: the first - through direct translation and assimilation of the works of ancient Greek scientists from Greek into Arabic in Khorezm. -

Mathematicians Timeline

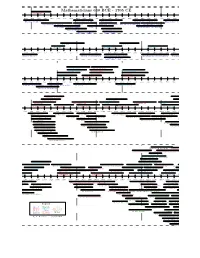

Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold Sergey Bernstein Gotthold Eisenstein Edmund Landau Issai Schur Leoplod Kronecker Paul Halmos Hermann Minkowski Hermann von Helmholtz Paul Erd}os Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Vladimir Steklov Karl Weierstrass Kurt G¨odel Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Andrei Markov Ernst Eduard Kummer Alexander Grothendieck Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Sofia Kovalevskya Andrey Kolmogorov Moritz Stern Friedrich Hirzebruch Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Georg Cantor Carl Goldschmidt Ferdinand von Lindemann Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Pafnuti Chebyshev Oscar Zariski Carl Gustav Jacobi F Georg Frobenius Peter Lax Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Solomon Lefschetz Julius Pl¨ucker Hermann Weyl Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Karl von Staudt Eugene Wigner Martin Ohm Emil Artin Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold August Ferdinand -

Universidade Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Tecnologia E Ciências Instituto De Matemática E Estatística

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Centro de Tecnologia e Ciências Instituto de Matemática e Estatística Pedro Henrique Vieira da Rosa Estudo analítico entre os sistemas de ensino da matemática no Irã e no Brasil: Uma proposta inovadora Rio de Janeiro 2019 Pedro Henrique Vieira da Rosa Estudo analítico entre os sistemas de ensino da matemática no Irã e no Brasil: uma proposta inovadora Dissertação apresentada, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Mestrado Profissional em Matemática em Rede Nacional - PROFMAT, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Younes Nikdelan Rio de Janeiro 2019 CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE UERJ / REDE SIRIUS / BIBLIOTECA CTC-A R788 Rosa, Pedro Henrique Vieira. Estudo analítico entre os sistemas de ensino da matemática no Irã e no Brasil: uma proposta inovadora / Pedro Henrique Vieira da Rosa. – 2019. 132f.: il. Orientador: Younes Nikdelan. Dissertação (Mestrado Profissional em Matemática Rede Nacional - PROFMAT), Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Matemática e Estatística. 1. Matemática - Estudo e ensino - Teses. 2. Matemática - Estudo e ensino - Irã - Teses. I. Nilkdealan, Younes. II. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Instituto de Matemática e Estatística. III. Título. CDU 51:37 Patricia Bello Meijinhos - CRB/5217- Bibliotecária responsável pela elaboração da ficha catalográfica Autorizo, apenas para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta dissertação, desde que citada a fonte. ______________________________ ________________________ Assinatura Data Pedro Henrique Vieira da Rosa Estudo analítico entre os sistemas de ensino da matemática no Irã e no Brasil: uma proposta inovadora Dissertação apresentada, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Mestrado Profissional em Matemática em Rede Nacional - PROFMAT, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.