Hamiduddin IHRH Chapter Oct2017final Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Rail and Tram Statistics, England: 2017/18

Statistical Release 28 June 2018 Light Rail and Tram Statistics, England: 2017/18 About this release This statistical release presents the latest annual information on light rail and tram systems in England during the 2017/18 covers light rail and tram use, infrastructure, revenue and passenger experience. This publication covers eight urban systems that are predominantly surface-running (see table 1 for a list of systems covered). Smaller systems, e.g. heritage railway and airport transit systems, are not included. London and Glasgow undergrounds and Edinburgh Trams are also excluded but statistics for these systems are However, outside London passenger journeys increased available online. by 2.4%. There were 267.2 million passengers journeys In this made on the eight light rail and tram systems in publication England, a 0.2% (416,000 passenger journeys) 3 passenger journeys decrease compared with the previous year. Passenger journeys 4 0.2% Concessionary journeys 6 decreased since 2009/10. since 2016/17 Vehicle mileage 7 Infrastructure 7 Despite this, passenger journeys on Blackpool Revenue 8 Tramway, Manchester Metrolink and Nottingham Express Transit increased when compared to the 45% Vehicle occupancy 9 previous year. of passenger Passenger satisfaction 9 journeys are by Docklands Contextual information 11 Almost half (45%) of journeys in 2017/18 Light Railway 12 consisted of those made on Docklands Light Background 15 Railway. RESPONSIBLE STATISTICIAN: Claire Pini AUTHOR: Fazeen Khamkar FURTHER INFORMATION: Media: 020 7944 3066 Public: 020 7944 3094 [email protected] Light Rail and Tram Factsheet Passenger journeys Concessionary journeys 15.4 passenger journeys passenger journeys passenger journeys per head 12% of all light rail passenger journeys were Passenger journeys decreased by 0.2% in 2017/18. -

Chronik Des Werra-Meißner-Kreises Anlässlich Des 40-Jährigen Jubiläums Der Kreisgründung

Chronik des Werra-Meißner-Kreises anlässlich des 40-jährigen Jubiläums der Kreisgründung Diese Publikation wurde durch die freundliche Unterstützung der Sparkasse Werra-Meißner möglich. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis / Impressum 1. Vorwort 3 2. Einleitung 4 3. Die territoriale Vorgeschichte der Region um Werra und Meißner 4 3.1. Von der Landvogtei an der Werra zum Distrikt Eschwege – Die Werra-Meißner-Region zwischen Spätmittelalter und Franzosenherrschaft 4 3.1.1. Der hessisch-thüringische Erbfolgekrieg 4 3.1.2. Die Städte und Ämter im Werraland 5 3.1.3. Die Landvogtei an der Werra 5 3.1.4. Die Landvogtei nach dem „Sterner“-Krieg 5 3.1.5. Landadel muss hessische Landeshoheit anerkennen 6 3.1.6. Das Werraland im „Ökonomischen Staat“ und seine Verwaltungsorganisation 6 3.1.7. Die Rotenburger Quart 7 3.1.8. Teil des „Königreiches Westphalen“ 7 4. Verwaltungsgeschichte der Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen 1821–1945 8 4.1. Die kurhessische Verwaltungsreform von 1821 und die Gründung der Landkreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen 8 4.1.1. Von der Kreisgründung 1821 bis zur bürgerlichen Revolution 1848 8 4.1.2. 1848 und die Folgen: Demokratisches Zwischenspiel 10 4.1.3. 1851–1866 11 4.1.4. Die Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen im Kaiserreich (1866–1918) 11 4.1.5. Kreis Eschwege 12 4.1.6. Kreis Witzenhausen 13 4.2. Die Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik und des „Dritten Reiches“ 1918–1945 14 4.2.1. Kreis Eschwege 14 4.2.2. Kreis Witzenhausen 17 5. Von der Stunde „Null “ zur Gebietsreform 21 5.1. Wiedergeburt der Demokratie und Integration der Flüchtlinge 21 5.2. -

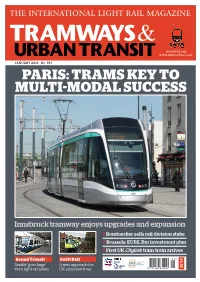

Paris: Trams Key to Multi-Modal Success

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com JANUARY 2016 NO. 937 PARIS: TRAMS KEY TO MULTI-MODAL SUCCESS Innsbruck tramway enjoys upgrades and expansion Bombardier sells rail division stake Brussels: EUR5.2bn investment plan First UK Citylink tram-train arrives ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Sound Transit Swift Rail 01 Seattle ‘goes large’ A new approach for with light rail plans UK suburban lines 9 771460 832043 For booking and sponsorship opportunities please call +44 (0) 1733 367600 or visit www.mainspring.co.uk 27-28 July 2016 Conference Aston, Birmingham, UK The 11th Annual UK Light Rail Conference and exhibition brings together over 250 decision-makers for two days of open debate covering all aspects of light rail operations and development. Delegates can explore the latest industry innovation within the event’s exhibition area and examine LRT’s role in alleviating congestion in our towns and cities and its potential for driving economic growth. VVoices from the industry… “On behalf of UKTram specifically “We are really pleased to have and the industry as a whole I send “Thank you for a brilliant welcomed the conference to the my sincere thanks for such a great conference. The dinner was really city and to help to grow it over the event. Everything about it oozed enjoyable and I just wanted to thank last two years. It’s been a pleasure quality. I think that such an event you and your team for all your hard to partner with you and the team, shows any doubters that light rail work in making the event a success. -

Göttingen Eichenberg Esch W Eg E Bebra Achtung: Baustellenbedingte

Montag - Freitag r 4 Linie RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 Verkehrsbeschränkungen Anmerkungen Göttingen ab 4.14 5.14 6.14 6.59 8.14 9.14 10.14 11.14 12.14 13.14 14.14 15.14 16.14 17.14 18.14 19.14 Friedland (Han) 4.23 5.24 6.23 7.09 8.23 9.23 10.23 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.23 17.23 18.23 19.23 Eichenberg an 4.28 5.28 6.28 7.14 8.28 9.28 10.28 11.28 12.28 13.28 14.28 15.28 16.28 17.28 18.28 19.28 RB87 Eichenberg ab 4.30 5.30 6.30 7.15 8.30 9.30 10.30 11.30 12.30 13.30 14.30 15.30 16.30 17.30 18.30 19.30 Bad Sooden-Allendorf 4.40 5.40 6.40 7.25 8.40 9.40 10.40 11.40 12.40 13.40 14.40 15.40 16.40 17.40 18.40 19.40 Eschwege-Niederhone 4.48 5.48 6.48 7.33 8.48 9.48 10.48 11.48 12.48 13.48 14.48 15.48 16.48 17.48 18.48 19.48 Eschwege an 4.51 5.51 6.51 7.36 8.51 9.51 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 16.51 17.51 18.51 19.51 Eschwege ab 4.59 5.59 6.59 7.59 8.59 9.59 10.59 11.59 12.59 13.59 14.59 15.59 16.59 17.59 18.59 19.59 Wehretal-Reichensachsen 5.06 6.06 7.06 8.06 9.06 10.06 11.06 12.06 13.06 14.06 15.06 16.06 17.06 18.06 19.06 20.06 Sontra 5.12 6.12 7.12 8.12 9.12 10.12 11.12 12.12 13.12 14.12 15.12 16.12 17.12 18.12 19.12 20.12 Bebra an 5.26 6.26 7.26 8.26 9.26 10.26 11.26 12.26 13.26 14.26 15.26 16.26 17.26 18.26 19.26 20.26 r RE5/RB5 Bebra ab 5.59 6.42 7.31 8.34 9.35 10.31 11.31 12.31 13.35 14.31 15.35 16.31 17.35 18.31 19.35 20.31 r RE5/RB5 Bad Hersfeld an 6.09 6.53 7.42 8.45 9.45 10.41 11.41 12.41 13.45 14.41 15.45 16.41 17.45 18.41 19.45 20.41 r RE5/RB5 Bebra ab 5.33 6.33 7.33 -

Format Acrobat

N° 88 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 1996-1997 Annexe tu procès-verbal de la séance du 21 novembre 1996. AVIS PRÉSENTÉ au nom de la commission des Affaires économiques et du Plan (1) sur le projet de loi de finances pour 1997, ADOPTÉ PAR L'ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE, TOME XVIII TRANSPORTS TERRESTRES Par M. Georges BERCHET, Sénateur. (1) Cette commission est composée de : MM. Jean François-Poncet, président ; Gérard Larcher, Henri Revol, Jean Huchon, Fernand Tardy, Gérard César, Louis Minetti, vice-présidents ; Georges Berchet, William Chervy, Jean-Paul Émin, Louis Moinard, secrétaires ; Louis Althapé, Alphonse Arzel, Mme Janine Bardou, MM. Bernard Barraux, Michel Bécot, Jean Besson, Claude Billard, Marcel Bony, Jean Boyer, Jacques Braconnier, Gérard Braun. Dominique Braye, Michel Charzat, Marcel-Pierre Cleach, Roland Courteau, Désiré Debavelaere, Gérard Delfau, Fernand Demilly, Marcel Deneux, Rodolphe Désiré, Jacques Dominati, Michel Doublet. Mme Josette Durrieu, MM. Bernard Dussaut, Jean-Paul Émorine, Léon Fatous, Hilaire Flandre, Philippe François, Aubert Garcia, François Gerbaud, Charles Ginésy, Jean Grandon, Francis Grignon, Georges Gruillot, Claude Haut, Mme Anne Heinis, MM. Pierre Hérisson, Rémi Herment, Bernard Hugo, Bernard Joly, Edmond Lauret, Jean-François Le Grand, Félix Leyzour, Kléber Malécot, Jacques de Menou, Louis Mercier, Mme Lucette Michaux-Chevry, MM. Jean-Marc Pastor, Jean Pépin, Daniel Percheron, Jean Peyrafitte, Alain Pluchet, Jean Pourchet, Jean Puech, Paul Raoult, Jean-Marie Rausch, Charles Revet, Roger Rigaudière, Roger Rinchet, Jean-Jacques Robert, Jacques Rocca Serra, Josselin de Rohan, René Rouquet, Raymond Soucaret, Michel Souplet, André Vallet, Jean-Pierre Vial. Voir les numéros : Assemblée nationale (l0ème législ.) : 2993. 3030 à 3035 et TA. 590. Sénat: 85 et 86 (annexe n° 18) (1996-1997). -

The International Light Rail Magazine

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com JUNE 2017 NO. 954 BLACKPOOL GOES FROM STRENGTH TO STRENGTH Sacramento: New lines and new life for San Jose cars US Congress rejects transit cutbacks Siemens and Bombardier to merge? Strasbourg opens cross-border link The art of track Saving Gent 06> £4.40 Challenges of design The impact and and maintenance legacy of the PCCs 9 771460 832050 Phil Long “A great event, really well organised and the dinner, reception and exhibition space made for great networking time.” Andy Byford – CEO, Toronto Transit Commission MANCHESTER “Once again your team have proved your outstanding capabilities. The content was excellent and the feedback from participants was great.” 18-19 July 2017 Simcha Ohrenstein – CTO, Jerusalem LRT Topics and themes for 2017 include: > Rewriting the business case for light rail investment > Cyber security – Responsibilities and safeguards > Models for procurement and resourcing strategies > Safety and security: Anti-vandalism measures > Putting light rail at the heart of the community > Digitisation and real-time monitoring > Street-running safety challenges > Managing obsolescence > Next-generation driver aids > Wire-free solutions > Are we delivering the best passenger environments? > Composite & materials technologies > From smartcard to smartphone ticketing > Rail and trackform innovation > Traction energy optimisation and efficiency > Major project updates Confirmed speakers include: SUPPORTED BY > Geoff Inskip – Chairman, UKTram > Danny Vaughan – Head -

Anlage 5 Tabellen Der Natura 2000-Gebiete, Die Mit Ihrem Größeren Flächenanteil in Einem Der Nachbarregierungsbezirke Liegen

Anlage 5 Tabellen der Natura 2000-Gebiete, die mit ihrem größeren Flächenanteil in einem der Nachbarregierungsbezirke liegen und daher in der dortigen Natura 2000-Verordnung gesichert werden. Sie sind in dieser Anlage nur nachrichtlich aufgeführt und in der Übersichtskarte (Anlage 2) zu dieser Verordnung nur nachrichtlich mit dünner blauer Schraffur dargestellt oder bei sehr schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässergebieten mit einem textli- chen Hinweis in der Karte „Rechtliche Sicherung durch das benannte Nachbarregierungspräsidium“ versehen. Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verord- nung mit dünner blauer Schraffur und Natura-Nummer nachrichtlich dargestellt werden NATURA_NR NAME HA REG_BEZ KREIS GEMEINDE 5518-301 Salzwiesen von Münzenberg 64.20 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Gießen, Münzenberg, Lich Gießen 5520-302 Talauen von Nidder und Hillersbach 253,90 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Gedern, Schotten bei Gedern und Burkhards Gießen 5520-306 Waldgebiete südlich und südwestlich 1680,60 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Hirzenhain, Nidda, Schot- von Schotten Gießen ten 5622-310 Steinaubachtal und Ürzeller Wasser 45,30 Darmstadt, Main-Kinzig-Kreis, Vogelsbergkreis Steinau an der Straße, Gießen Schlüchtern, Freiensteinau Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässer-FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verordnung mit dem textlichen Hinweis -

Sas Ile Folien Amenagement De L'ile Folien a Valenciennes (59)

Aménagement de l’Ile Folien – Valenciennes (59) S.A.S. Ile Folien Etude d’impact sur l’environnement S.A.S. ILE FOLIEN AMENAGEMENT DE L’ILE FOLIEN A VALENCIENNES (59) Etude d’impact sur l’environnement 11010018-V1 Version 4 du 05/07/2016 1 Aménagement de l’Ile Folien – Valenciennes (59) S.A.S. Ile Folien Etude d’impact sur l’environnement 11010018-V1 2 Version 4 du 05/07/2016 Aménagement de l’Ile Folien – Valenciennes (59) S.A.S. Ile Folien Etude d’impact sur l’environnement SOMMAIRE CHAPITRE 6. COUTS COLLECTIFS DES POLLUTIONS ET NUISANCES ET DES AVANTAGES INDUITS POUR LA COLLECTIVITE ..................................... 203 CHAPITRE 1. RESUME NON TECHNIQUE .......................................... 9 CHAPITRE 7. ANALYSE EFFETS NEGATIFS ET POSITIFS, DIRECTS ET INDIRECTS, TEMPORAIRES ET PERMANENTS A COURT MOYEN ET LONG TERME ET DES MESURES , , PRISES POUR REDUIRE, SUPPRIMER OU COMPENSER ............................... 205 CHAPITRE 2. CADRE REGLEMENTAIRE .......................................... 19 7.1 IMPACTS, MESURES, SUIVIS ET COUTS LIES AU MILIEU PHYSIQUE ................ 206 2.1 CONTEXTE REGLEMENTAIRE .................................................... 20 7.2 IMPACTS, MESURES ET COUTS LIES AU PATRIMOINE NATUREL ................... 214 2.2 LES TEXTES .................................................................... 21 7.3 IMPACTS, MESURES, SUIVI ET COUTS LIES A LA SANTE, AU CADRE DE VIE, AUX RISQUES ET AUX POLLUTIONS.................................................. 232 7.4 IMPACTS, MESURES, SUIVI ET COUTS LIES AU MILIEU HUMAIN -

Territorial Opportunities of Tram-Based Systems Cyprien Richer, Sophie Hasiak

Territorial opportunities of tram-based systems Cyprien Richer, Sophie Hasiak To cite this version: Cyprien Richer, Sophie Hasiak. Territorial opportunities of tram-based systems: Comparative analysis between Nottingham (UK) and Valenciennes (FRA). Town Planning Review, Liverpool University Press, 2014, 85 (2), pp.217-236. halshs-00993568 HAL Id: halshs-00993568 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00993568 Submitted on 6 Mar 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Town Planning Review Special Issue “Has rail saved the city? - Rail and Urban Development in Comparative Perspective“ Territorial opportunities of tram-based systems: Comparative analysis between Nottingham (UK) and Valenciennes (FRA) Cyprien Richer and Sophie Hasiak Cerema (Center for studies and expertise on Risks, Environment, Mobility, and Urban and Country Planning) Territorial Division for the Northern and Picardie Regions, 2 rue de Bruxelles CS 20275, 59019 Lille email: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Within the European project « Sintropher », this paper focuses on a comparative analysis between two tramway systems in Nottingham (UK) and Valenciennes (FRA). The aim is to understand how these tram-based systems were successfully integrated in the urban areas. -

Final Thesis MULTICRITERIA ANALYSIS to RELAUNCH SANGRITANA S.P.A. RAILWAYS in the LANCIANO AREA

FACULTY OF CIVIL AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING MASTER’S DEGREE IN TRANSPORT SYSTEMS ENGINEERING Final Thesis MULTICRITERIA ANALYSIS TO RELAUNCH SANGRITANA S.p.A. RAILWAYS IN THE LANCIANO AREA SEVKET OGUZ KAGAN CAPKIN Matricola.1784288 Relatore PROF. MARIA VITTORIA CORAZZA A.Y. 2018-2019 Summary ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................ 3 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 8 1. Information about Travel Mode Chosen by The Users .................................................... 8 2. Public Transportation in Italy ............................................................................................ 11 3. Definition of Tram-Train ..................................................................................................... 15 4. Features of the Tram-Train Systems .................................................................................. 17 5. Examples of Tram-Train Services in European Union -

Folgende Ortsteile Wurden Im Rahmen Des Breitbandausbaus Nordhessen Erschlossen

Folgende Ortsteile wurden im Rahmen des Breitbandausbaus Nordhessen erschlossen: Landkreis PLZ Gemeinde Ortsteil Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Heinebach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Hergershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Licherode Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Niederellenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Oberellenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36211 Alheim Sterkelshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Allmershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Beiershausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Heenes Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36251 Bad Hersfeld Kohlhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Blankenheim Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Breitenbach Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Iba Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Imshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Lüdersdorf Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Rautenhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36179 Bebra Solz Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Breitenbach a. H. Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Gehau Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Hatterode Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Machtlos/B. Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36287 Breitenbach am Herzberg Oberjossa Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Cornberg Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Königswald Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36219 Cornberg Rockensüß Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Friedewald Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Hillartshausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Lautenhausen Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36289 Friedewald Motzfeld Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36282 Hauneck Bodes Hersfeld-Rotenburg 36166 Haunetal -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [Rutgers University] On: 3 October 2008 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 788777707] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Transport Reviews Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713766937 Urban transport in Germany: providing feasible alternatives to the car John Pucher a a Department of Urban Planning, Rutgers University, Bloustein School of Public Policy, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA Online Publication Date: 01 October 1998 To cite this Article Pucher, John(1998)'Urban transport in Germany: providing feasible alternatives to the car',Transport Reviews,18:4,285 — 310 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/01441649808717020 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01441649808717020 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.