Agatha: Slavic Versus Salian Solutions -31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding Neil Oliver, “History of Scotland” BBC2, 2009 “ The many armies, tens of thousands of warriors clashed at the site known as Brunanburh where the Mersey Estuary enters the sea . For decades afterwards it was simply known called the Great Battle. This was the mother of all dark-age bloodbaths and would define the shape of Britain into the modern era. Althouggg,h Athelstan emerged victorious, the resistance of the northern alliance had put an end to his dream of conquering the whole of Britain. This had been a battle for Britain, one of the most important battles in British historyyy and yet today ypp few people have even heard of it. 937 doesn’t quite have the ring of 1066 and yet Brunanburh was about much more than blood and conquest. This was a showdown between two very different ethnic identities – a Norse-Celtic alliance versus Anglo-Saxon. It aimed to settle once and for all whether Britain would be controlled by a single Imperial power or remain several separate kingdoms. A split in perceptions which, like it or not, is still with us today”. Some of the people who’ve been trying to sort it out Nic k Hig ham Pau l Cav ill Mic hae l Woo d John McNeal Dodgson 1928-1990 Plan •Background of Brunanburh • Evidence for Wirral location for the battle • If it did happen in Wirra l, w here is a like ly site for the battle • Consequences of the Battle for Wirral – and Britain Background of Brunanburh “Cherchez la Femme!” Ann Anderson (1964) The Story of Bromborough •TheThe Viking -

St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman's

2021 VIII The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B. R. Massey Article: The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B.R. Massey MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY Abstract: James VI of Scotland’s succession to the English throne as James I in 1603 was usually justified by contemporaries on the grounds that James was Henry VII’s senior surviving descendant, making him the rightful hereditary claimant. Some works, however, argued that James also had the senior Saxon hereditary claim to the English throne due his descent from St Margaret of Scotland—making his hereditary claim superior to that of any English monarch from William the Conqueror onwards. Morgan Colman’s Arbor Regalis, a large and impressive genealogy, was a visual assertion of this argument, showing that James’s senior hereditary claims to the thrones of both England and Scotland went all the way back to the very foundations of the two kingdoms. This article argues that Colman’s genealogy could also be interpreted in support of James’s Anglo-Scottish union project, showing that the permanent union of England and Scotland as Great Britain was both historically legitimate and a justifiable outcome of James’s combined hereditary claims. Keywords: Jacobean; genealogies; Great Britain; hereditary right; succession n 24 March 1603, Queen Elizabeth I of England died and her Privy Council proclaimed that James VI, King of Scots, had succeeded as King of England. -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Eric J. Hobsbawm, Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959). 2. Eric J. Hobsbawm, Bandits, rev. ed. (1961; New York: Pantheon, 1981), p. 23. 3. Ibid., p. 17. 4. Ibid., pp. 22–28. 5. Anton Blok, “The Peasant and the Brigand: Social Banditry Reconsidered,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 1:4 (1972), 494–503. See also Richard W. Slatta, ed., Bandidos: The Varieties of Latin American Banditry (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1987). 6. See the summary by Richard W. Slatta, “Eric J. Hobsbawm’s Social Bandit: A Critique and Revision,” A Contracorriente 1:2 (2004), 22–30. 7. Paul Kooistra, Criminals as Heroes: Structure, Power, and Identity (Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1989), p. 29. 8. See Steven Knight’s Robin Hood: A Complete Study of the English Outlaw (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994); and Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003). 9. Mary Grace Duncan, Romantic Outlaws, Beloved Prisons: the Unconscious Meanings of Crime and Punishment (New York: New York University Press, 1996), p. 61. 10. Charles Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (London, 1841). 11. See, for instance, Kenneth Munden, “A Contribution to the Psychological Understanding of the Cowboy and His Myth,” American Imago Summer (1958), 103–48. 12. William Settle, for instance, makes the argument in the introduction to his Jesse James Was His Name (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1966). 13. Hobsbawm, Bandits, pp. 40–56. 14. Joseph Ritson, ed., Robin Hood: A Collection of all the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, now Extant Relative to that Celebrated English Outlaw, 2 vols (London: Egerton and Johnson, 1795; rpt. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Textual Englishness, 1175 – 1330 Joseph Richard Wingenbach Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 “Þe Inglis in seruage”: Textual Englishness, 1175 – 1330 Joseph Richard Wingenbach Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wingenbach, Joseph Richard, "“Þe Inglis in seruage”: Textual Englishness, 1175 – 1330" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 844. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/844 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “ÞE INGLIS IN SERUAGE”: TEXTUAL ENGLISHNESS, 1175 – 1330 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State Univeristy and Agricultural and Mechanical in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Joseph Wingenbach B.A., Randolph-Macon College, 2002 M.A., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2007 May 2016 This is study is dedicated to the memory of Lisi Oliver: advisor, mentor, and friend. ii Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………..... iv Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter I. “Wher beth they biforn us weren”: Old English Epic Poetry and Middle English Romance ………………….......................................................................................… 47 II.“Ne may non ryhtwis king [ben] vnder Criste seoluen, bute-if he beo in boke ilered”: The Ingenious Compilator of the Proverbs of Alfred ………………..........……….... 143 III.The Castle and the Stump: The Owl and the Nightingale and English Identity...... -

Converted by Filemerlin

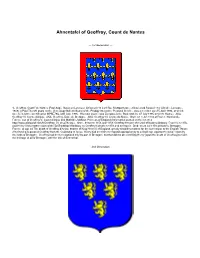

Ahnentafel of Geoffroy, Count de Nantes --- 1st Generation --- 1. Geoffroy, Count1 de Nantes (Paul Augé, Nouveau Larousse Universel (13 à 21 Rue Montparnasse et Boulevard Raspail 114: Librairie Larousse, 1948).) (Paul Theroff, posts on the Genealogy Bulletin Board of the Prodigy Interactive Personal Service, was a member as of 5 April 1994, at which time he held the identification MPSE79A, until July, 1996. His main source was Europaseische Stammtafeln, 07 July 1995 at 00:30 Hours.). AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte d'Anjou. AKA: Geoffroy, Duke de Bretagne. AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte du Maine. Born: on 3 Jun 1134 at Rouen, Normandie, France, son of Geoffroy V, Count d'Anjou and Mathilde=Mahaut, Princess of England (Information posted on the Internet, http://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Geoffroy_VI_d%27Anjou.). Note - between 1156 and 1158: Geoffroy became the Lord of Nantes (Brittany, France) in 1156, and Henry II his brother claimed the overlordship of Brittany on Geoffrey's death in 1158 and overran it. Died: on 26 Jul 1158 at Nantes, Bretagne, France, at age 24 The death of Geoffroy d'Anjou, brother of King Henry II of England, greatly simplifies matters for the succession to the English Throne. After having separated Geoffroy from the Countship of Anjou, Henry had sent him to respond appropriatetly to a challenge against the ducal crown by the lords of Bretagne. Geoffroy had been recognized only by part of Bretagne, but that did not prevent King Henry [upon the death of Geoffroy] to claim the heritage of all of Bretagne, with the title of Seneschal. --- 2nd Generation --- Coat of Arm associated with Geoffroy V, Comte d'Anjou. -

O'neal Dissertation

© Copyright by Amy Michele O’Neal May, 2008 PRAGMATISM, PATRONAGE, PIETY AND PARTICIPATION: WOMEN IN THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLES ______________________________________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ By Amy Michele O’Neal May, 2008 ii PRAGMATISM, PATRONAGE, PIETY AND PARTICIPATION: WOMEN IN THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLES By: _______________________________ Amy Michele O’Neal Approved: ____________________________________ Sally N. Vaughn, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________________ Catherine F. Patterson, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Patricia R. Orr, Ph.D. _____________________________________ John A. Moretta, Ph.D. ______________________________________ John J. Antel, Ph.D. Dean, College of Humanities and Fine Arts Department of Economics iii PRAGMATISM, PATRONAGE, PIETY AND PARTICIPATION: WOMEN IN THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLES An Abstract to the Doctoral Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Amy Michele O’Neal May, 2008 iv PRAGMATISM, PATRONAGE, PIETY AND PARTICIPATION: WOMEN IN THE ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLES This dissertation examines the chronicles written in England and Normandy in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and explores how the writers of these histories perceived women. This study is meant to illuminate the lives of the women in the Anglo-Norman chronicles at every stage of life. While many modern books have addressed medieval women, they have attempted to deal with women more generally, looking at many areas and societies over hundreds of years. Other modern historians have focused on a few select women using evidence from the same Anglo-Norman chronicles used in this study. -

Russian Viking and Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY RUSSIAN/VIKING ANCESTRY Direct Lineage from: Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus to: Lars Erik Granholm 1 Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus b. 830 d. 879 m. Efenda (Edvina) Novgorod m. ABT 876 b. ABT 850 2 Igor Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 835 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia d. 945 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia m. Olga Prekrasa of Kiev b. ABT 890 d. 11 Jul 969 Kiev 3 Sviatoslav I Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 942 d. MAR 972 m. Malusha of Lybeck b. ABT 944 4 Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev b. 960 Kiev, Ukraine d. 15 Jul 1015 Berestovo, Kiev m. Rogneda Princess of Polotsk b. 962 Polotsk, Byelorussia d. 1002 [daughter of Ragnvald Olafsson Count of Polatsk] m. Kunosdotter Countess of Oehningen [Child of Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev and Rogneda Princess of Polotsk] 5 Yaroslav I the Wise Grand Duke of Kiew b. 978 Kiev d. 20 Feb 1054 Kiev m. Ingegerd Olofsdotter Princess of Sweden m. 1019 Russia b. 1001 Sigtuna, Sweden d. 10 Feb 1050 [daughter of Olof Skötkonung King of Sweden and Estrid (Ingerid) Princess of Sweden] 6 Vsevolod I Yaroslavich Grand Prince of Kiev b. 1030 d. 13 Apr 1093 m. Irene Maria Princess of Byzantium b. ABT 1032 Konstantinopel, Turkey d. NOV 1067 [daughter of Constantine IX Emperor of Byzantium and Sclerina Empress of Byzantium] 7 Vladimir II "Monomach" Grand Duke of Kiev b. 1053 d. 19 May 1125 m. Gytha Haraldsdotter Princess of England m. 1074 b. ABT 1053 d. 1 May 1107 [daughter of Harold II Godwinson King of England and Ealdgyth Swan-neck] m. -

Welsh Kings at Anglo-Saxon Royal Assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Keynes The Henry Loyn Memorial Lecture for 2008 Welsh kings at Anglo-Saxon royal assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes A volume containing the collected papers of Henry Loyn was published in 1992, five years after his retirement in 1987.1 A memoir of his academic career, written by Nicholas Brooks, was published by the British Academy in 2003.2 When reminded in this way of a contribution to Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman studies sustained over a period of 50 years, and on learning at the same time of Henry’s outstanding service to the academic communities in Cardiff, London, and elsewhere, one can but stand back in awe. I was never taught by Henry, but encountered him at critical moments—first as the external examiner of my PhD thesis, in 1977, and then at conferences or meetings for twenty years thereafter. Henry was renowned not only for the authority and crystal clarity of his published works, but also as the kind of speaker who could always be relied upon to bring a semblance of order and direction to any proceedings—whether introducing a conference, setting out the issues in a way which made one feel that it all mattered, and that we stood together at the cutting edge of intellectual endeavour; or concluding a conference, artfully drawing together the scattered threads and making it appear as if we’d been following a plan, and might even have reached a conclusion. First place at a conference in the 1970s and 1980s was known as the ‘Henry Loyn slot’, and was normally occupied by Henry Loyn himself; but once, at the British Museum, he was for some reason not able to do it, and I was prevailed upon to do it in his place. -

2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER the JOURNAL of the LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A

ISSN 0950 - 2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER THE JOURNAL OF THE LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A. Clayton EDITORIAL 3 CLUB TALKS From Gothic to Roman: Letter Forms on the Tudor Coinage, by Toni Sawyer 5 Scottish Mints, by Michael Anderson 23 Members' Own Evening 45 Mudlarking on the Thames, by Nigel Mills 50 Patriotics and Store Cards: The Tokens of the American 1 Civil War, by David Powell 64 London Coffee-house Tokens, by Robert Thompson 79 Some Thoughts on the Copies of the Coinage of Carausius and Allectus, by Hugh Williamson 86 Roman Coins: A Window on the Past, by Ian Franklin 93 AUCTION RESULTS, by Anthony Gilbert 102 BOOK REVIEWS 104 Coinage and Currency in London John Kent The Token Collectors Companion John Whitmore 2 EDITORIAL The Club, once again, has been fortunate in having a series of excellent speakers this past year, many of whom kindly supplied scripts for publication in the Club's Newsletter. This is not as straightforward as it may seems for the Editor still has to edit those scripts from the spoken to the written word, and then to type them all into the computer (unless, occasionally, a disc and a hard copy printout is supplied by the speaker). If contributors of reviews, notes, etc, could also supply their material on disc, it would be much appreciated and, not least, probably save a lot of errors in transmission. David Berry, our Speaker Finder, has provided a very varied menu for our ten meetings in the year (January and August being the months when there is no meeting). -

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti Eethelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti EEthelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi Nicola Jane Robertson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, Centre for Medieval Studies, September 2003 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Mary Swan and Professor Ian Wood for their guidance and support throughout the course of this project. Professor Wood's good-natured advice and perceptive comments have helped guide me over the past four years. Dr Swan's counsel and encouragement above and beyond the call of duty have kept me going, especially in these last, most difficult stages. I would also like to thank Dr William Flynn, for all his help with my Latin and useful commentary, even though he was not officially obliged to offer it. My advising tutor Professor Joyce Hill also played an important part in the completion of this work. I should extend my gratitude to Alison Martin, for a constant supply of stationery and kind words. I am also grateful for the assistance of the staff of the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. I would also like to thank all the students of the Centre for Medieval Studies, past and present, who have always offered a friendly and receptive environment for the exchange of ideas and assorted cakes. -

The Annals of Herman of Niederaltaich, 1236-60 Herman

1 The Annals of Herman of Niederaltaich, 1236-60 Herman was abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Niederaltaich in the diocese of Passau from October 1242 until his resignation on grounds of old age in March 1273. He died two years later, on 31st July 1275. He wrote a number of historical works about his monastery, and continued an existing abbey chronicle, on which he began to work after 1251; although he would seem to have gone back to continue the account from 1235 onwards. (The entries for these earlier years are clearly retrospective). His chronicle is a contemporary Bavarian witness of the German crisis of the mid-thirteenth century, and especially insofar as it affected Bavaria and Austria. Niederaltaich, founded in the mid- eighth century, was one of the most ancient and prestigious monasteries in Bavaria. [Translated from Hermanni Altahensis Annales, MGH SS xvii.392-402; translation (c) G.A. Loud (2010)] (1236) Duke Frederick of Austria and Styria was outlawed by the emperor at Augsburg. 1 This Frederick was a severe man, great-hearted in battle, strict and cruel in justice, greedy in amassing treasures, who so spread terror both among his own subjects and neighbouring peoples that he was not only not loved but was feared by all. For he led a campaign with his army into Moravia against King Wenceslas of the Bohemians, and when he also entered the land of Hungary he ravaged the bounds of both lands with fire and sword. He strove to oppress the nobles and better people of his land and to exalt the ignoble.