Cosmos, Chaos: Finance, Power and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Out of the Ordinary: Finding Hidden Threats by Analyzing Unusual

RAND-INITIATED RESEARCH CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available CIVIL JUSTICE from www.rand.org as a public service of EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE Jump down to document6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit POPULATION AND AGING research organization providing PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges TERRORISM AND facing the public and private sectors HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND around the world. INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND-Initiated Research View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Out of the Ordinary Finding Hidden Threats by Analyzing Unusual Behavior JOHN HOLLYWOOD, DIANE SNYDER, KENNETH McKAY, JOHN BOON Approved for public release, distribution unlimited This research in the public interest was supported by RAND, using discretionary funds made possible by the generosity of RAND's donors, the fees earned on client-funded research, and independent research and development (IR&D) funds provided by the Department of Defense. -

September 11 Attacks

Chapter 1 September 11 Attacks We’re a nation that is adjusting to a new type of war. This isn’t a conventional war that we’re waging. Ours is a campaign that will have to reflect the new enemy…. The new war is not only against the evildoers themselves; the new war is against those who harbor them and finance them and feed them…. We will need patience and determination in order to succeed. — President George W. Bush (September 11, 2001) Our company around the world will continue to operate in this sometimes violent world in which we live, offering products that reach to the higher and more positive side of the human equation. — Disney CEO Michael Eisner (September 11, 2001) He risked his life to stop a tyrant, then gave his life trying to help build a better Libya. The world needs more Chris Stevenses. — U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (September 12, 2012) We cannot have a society in which some dictators someplace can start imposing censorship here in the United States because if somebody is able to intimidate us out of releasing a satirical movie, imagine what they start doing once they see a documentary that they don’t like or news reports that they don’t like. That’s not who we are. That’s not what America is about. — President Barack Obama (December 19, 2014) 1.1 September 11, 2001 I was waking up in the sunny California morning on September 11, 2001. Instead of music playing on my radio alarm clock, I was hearing fragments of news broadcast about airplanes crashing into the Pentagon and the twin towers of the World Trade Center. -

Some Visualization Challanges From

' $ Some visualization challenges from SNA Vladimir Batagelj University of Ljubljana Slovenia Workshop on Network Analysis and Visualisation In conjunction with Graph Drawing 2005 September 11, 2005, Limerick, Ireland & version: November 6, 2015 / 02 : 03% V. Batagelj: Some visualization challenges from SNA I-2 ' $ Outline 1 Some Examples..................................1 13 Networks...................................... 13 15 Types of networks................................. 15 20 Large Networks.................................. 20 21 Pajek ....................................... 21 23 Analysis and Visualization............................. 23 25 Representations of properties............................ 25 35 Large networks................................... 35 39 Dense networks.................................. 39 44 New graphical elements.............................. 44 46 Dynamic/temporal networks............................ 46 51 Challenges..................................... 51 Workshop on Network Analysis and Visualisation, September 11, 2005, Limerick, Ireland & s s y s l s y s s *6% V. Batagelj: Some visualization challenges from SNA 1 ' $ Some Examples The use of networks was introduced in sociology by Moreno developing the sociometry (1934, 1953, 1960). An overview of visualization of so- cial networks was prepared by Lin Freeman(1,2). The Ars Electronica 2004 in Linz, Austria gave special attention to networks by the exhibition Lan- Moreno guage of Networks (1,2,3,4). Some of the following examples are from the Gerhard -

The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2013 The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace Randal Sean Harrison Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Communication Commons Copyright 2013 Randal Sean Harrison Recommended Citation Harrison, Randal Sean, "The Problematic of Privacy in the Namespace", Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2013. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/666 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Communication Commons THE PROBLEMATIC OF PRIVACY IN THE NAMESPACE By Randal Sean Harrison A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In Rhetoric and Technical Communication MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Randal Sean Harrison This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Rhetoric and Technical Communication. Department of Humanities Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Daryl Slack Committee Member: Dr. Patty Sotirin Committee Member: Dr. Diane Shoos Committee Member: Dr. Charles Wallace Department Chair: Dr. Ronald Strickland I dedicate this work to my family for loving and supporting me, and for patiently bearing with a course of study that has kept me away from home far longer than I’d wished. I dedicate this also to my wife Shreya, without whose love and support I would have never completed this work. 4 Table of Contents Chapter 1. The Problematic of Privacy ........................................................................ 7 1.1 Privacy in Crisis ................................................................................................ -

Project Responder: National Technology Plan For

Project Responder: Project Responder National Technology Plan for Emergency Response to Catastrophic Terrorism National Technology Plan for Emergency Response to Catastrophic Terrorism April 2004 Prepared by Hicks and Associates, Inc. for The National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism and the United States Department of Homeland Security April 2004 Project Responder National Technology Plan for Emergency Response to Catastrophic Terrorism Edited by Thomas M. Garwin, Neal A. Pollard, and Robert V. Tuohy April 2004 Prepared by Hicks and Associates, Inc. for The National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism and the United States Department of Homeland Security Supported under Award Number MIPT106-113-2000-002, Project Responder from the Oklahoma City National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) and the Office of Domestic Preparedness, Department of Homeland Security. Points of view in this document are those of the editors and/or authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of MIPT or the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. ii PROJECT RESPONDER Executive Summary Executive Summary Purpose and Vision – Project Responder • Response and Recovery The National Memorial Institute for the • Emergency Management Preparation and Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) in Oklahoma Planning City focuses on “preventing and deterring terror- ism or mitigating its effects.” Since April 2001, • Medical Response MIPT has supported Hicks & Associates, Inc. in developing a National Technology Plan for • Public Health Readiness for Biological Agent Emergency Response to Catastrophic Terrorism, Events pursuant to a guiding vision: • Logistics Support Emergency responders should have the capability to prevent or mitigate terrorist use of chemical, biolog- • Crisis Evaluation and Management ical, radiological, nuclear, or high explosive/incen- • All-Source Situational Understanding diary (CBRNE) devices and emerging threats. -

Transparent World Minoritarian Tactics in the Age of Transparency

Interface Criticism | out: Culture and Politics Transparent World Minoritarian Tactics in the Age of Transparency by inke arns Giedion, Mendelsohn, Corbusier turned the abiding places of man into a transit area for every conceivable kind of energy and for electric currents and radio waves. The time that is coming will be dominated by transparency (Benjamin, “The Return of the Flâneur”). The coils of a serpent are even more complex than the burrows of a molehill (Deleuze). During the Cold War, the unimaginable usually came in the guise of a threat from outer space (which in western science-fiction was not infrequently a code word for communism), whereas today the unimaginable has moved almost indecently close to us. It is in our immediate proximity, on and in our own bodies. The production of unimaginably small nanomachines equipped with all kinds of capa- bilities is not the sole evidence of this development, as the transfor- mation of matter itself has become an ‘immaterial.’ The notion of ‘immaterials’ was coined by Jean-François Lyotard in 1985 with his ex- hibition “Les Immatériaux” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. ‘Imma- terial’ in his sense is not the equivalent of ‘immaterial’ (= opposite of 253 matter), but denotes new extensions of material that exclude the pos- sibility of direct human access: The good old matter itself comes to us in the end as some- thing which has been dissolved and reconstructed into complex formulas. Reality consists of elements, organised by structural rules (matrixes) in no longer human measures of space and time.1 At first glance, these immaterials are indistinguishable from the materials we know of old. -

Rdt&E Budget Item Justification Sheet

UNCLASSIFIED DATE RDT&E BUDGET ITEM JUSTIFICATION SHEET (R-2 Exhibit) February 2002 APPROPRIATION/BUDGET ACTIVITY R-1 ITEM NOMENCLATURE RDT&E, Defense-wide Command, Control and Communications Systems BA3 Advanced Technology Development PE 0603760E, R-1 #48 Cost To FY 2001 FY 2002 FY 2003 FY 2004 FY 2005 FY 2006 FY 2007 Total Cost COST (In Millions) Complete Total Program Element (PE) 129.162 115.149 130.101 182.889 225.085 276.986 313.089 Continuing Continuing Cost Command & Control 73.126 65.029 76.601 109.336 149.726 195.838 209.384 Continuing Continuing Information Systems CCC-01 Information Integration 56.036 50.120 53.500 73.553 75.359 81.148 103.705 Continuing Continuing Systems CCC-02 (U) Mission Description: (U) This program element is budgeted in the Advanced Technology Development Budget Activity because its purpose is to demonstrate and evaluate advanced information systems research and development concepts. (U) The goals in of the Command and Control Information Systems project are to develop and test innovative, secure architectures and tools to enhance information processing, dissemination and presentation capabilities for the commander. This will give the commander insight into the disposition of enemy and friendly forces, a joint situational awareness picture that will improve planning, decision-making and execution support capability, and provide secure multimedia information interfaces and assured software to “on the move users”. Integration of collection management, planning and battlefield awareness programs is an essential element for achieving battlefield dominance through assured information systems. The project will also focus on information techniques to counter terrorism. -

Anglo-American Privacy and Surveillance Laura K

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 96 Article 8 Issue 3 Spring Spring 2006 Anglo-American Privacy and Surveillance Laura K. Donohue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Laura K. Donohue, Anglo-American Privacy and Surveillance, 96 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1059 (2005-2006) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/06/9603-1059 THE JOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 96, No. 3 Copyright 0 2006 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in US.A. CRIMINAL LAW ANGLO-AMERICAN PRIVACY AND SURVEILLANCE LAURA K. DONOHUE* TABLE OF CONTENTS IN TROD UCTION ........................................................................................ 106 1 I. SURVEILLANCE AND THE LAW INTHE UNITED STATES ....................... 1064 A. REASONABLE EXPECTATION OF PRIVACY ............................ 1065 B. NATIONAL SECURITY AND SURVEILLANCE .......................... 1072 1. The R ed Scare............................................................................. 1073 2. Title III ........................................................................................ 10 7 7 3. Executive Excess ........................................................................ -

Breaking Down the State

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS 55 PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Duyvendak (eds) & Jasper Breaking Down the State: Protestors Engaged continues the new effort to analyze politics as the interplay of various players within structured arenas that its companion volume, Players and Arenas: The Interactive Dynamics of Protest, started. It breaks down the state into the players that really matter, and which really make decisions and pursue coherent strategies, moving beyond the tendency to lump various agencies together as ‘the state’. Breaking Down the State brings together world-famous experts on the interactions between political protestors and the many parts of the state, including courts, political parties, legislators, police, armies, and intelligence services. Jan Willem Duyvendak is a sociologist at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper is a sociologist at the CUNY Graduate Center, New York. They both have written a number of books on recent social movements, and are the co-editors of AUP’s book series Protest and Social Movements. State the Down Breaking Edited by Jan Willem Duyvendak and James M. Jasper Breaking Down the State Protestors Engaged ISBN: 978-90-8964-759-7 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 0 8 9 6 4 7 5 9 7 Breaking Down the State Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. -

On Their Own Terms: a Lexicon with an Emphasis on Information-Related Terms Produced by the U.S. Federal Government

Notes on the 6th edition.........................1 On Their Own Terms: A Lexicon with an Introduction..........................................2 – 15 Emphasis on Information-Related Terms Produced by the U.S. Federal Government Creative Commons License...................16 How to Cite this Work...........................16 Susan Maret, Ph.D. (6th ed., revised 2016) Contact Information.............................16 Terms ..................................................17- 432 Notes on the 6th edition Since the first edition in 2005, On Their on Terms has reported language that reflects the scope of U.S. information policy. Now in its sixth edition, the Lexicon features new terms that further chronicle the federal narrative of information and its relationship to national security, intelligence operations, freedom of information, privacy, technology, and surveillance, as well as types of war, institutionalized secrecy, and censorship. This edition also lists information terms of note that arise from popular culture, the scholarly literature, and I find interesting to federal information policy and the study of information. This edition of the Lexicon emphasizes the historical aspects of U.S. information policy and associated programs in that it is a testament to the information politics of specific presidential administrations, of particular the Bush-Cheney and Obama years; there is also a look back to historical agency record keeping practices such as the U.S. Army’s computerized personalities database, discovered in a 1972 congressional -

Governing by Networks (Sept. 2003)

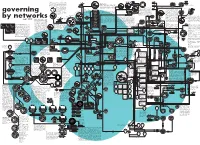

Deep Space Network -DSN CALEA redefines the ave Eme rnet Rese A cell-phone's Sim card W rg te a telecommunications industry’s d e n rc Nordnet can be located thanks obligation to assist law enforcement n n I h u c GWEN Ground Wave y Japan Verio 4 o y Netw Tracking & Data r G to one of the 30,000 in executing lawfully authorized r ? Emergency Network ce o # a RSN r r VERIO N a k t A E o G T p Relay Satellite Syst. TDRSS base stations of the M e electronic surveillance. In 1991, the - u e The Ground Wave Emergency Network (GWEN) S n largest global website hosting p t ? D LF/UHF w p GSM network or to one FBI held a series of secret meetings provides survivable connectivity to designated bomber a NTT S l Telstra e I ? P company p o N traffic exchange via BBN (Genuity) e r of the satellites used by with EU member states to persuade and tanker bases. The system is in sustainment. GWEN N r e t k D Global One (cable) R n survivable I the GPS (Global G them to incorporate CALEA into ( is designed as an ultra-high powered VLF [150-175 # ESSAIM G space network W omm traffic exchange Positioning System) E C u N European law. The meetings ) kHz] network intended to survive massive broadband space y n probe x ic included representatives from destructive interference produced by nuclear EMP. probe a a NTT l t Galaxy Communicator is an open source partnership Glob o State of Japan owns 66% al Canada, Hong Kong, Australia and GWEN is Scheduled to be Replaced by SCAMP in a ? ) S r architecture for constructing dialogue systems. -

Department of Defense FY 2003 Budget Estimate Feburary 2002

UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defense FY 2003 Budget Estimate Feburary 2002 NT OF E D M E T F R E A N P S E E D U N A I IC T R ED E S AM TATE S OF RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, TEST AND EVALUATION, DEFENSE-WIDE Volume 1 Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency UNCLASSIFIED DEFENSE ADVANCED RESEARCH PROJECTS AGENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME 1 SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS (ALL VOLUMES)…………………………………………………………………………………I TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME 1 IN R-1 ORDER………………………………………………………………………………II TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME 1 IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER………………………………………………………………III R-1 EXHIBIT FOR DARPA…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………IV R-1 NUMBER DARPA PAGE 2 0601101E Defense Research Science…………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 14 0602301E Computing Systems and Communications Technology…………………………………………………………… 31 15 0602302E Embedded Software and Pervasive Computing …………………………………………………………………… 89 16 0602383E Biological Warfare Defense………………………………………………………………………………………… 105 18 0602702E Tactical Technology………………………………………………………………………………………………… 122 20 0602712E Materials and Electronics Technology……………………………………………………………………………… 153 36 0603285E Advanced Aerospace Systems……………………………………………………………………………………… 192 45 0603739E Advanced Electronics Technologies………………………………………………………………………………… 218 48 0603760E Command, Control and Communications Systems………………………………………………………………… 246 49 0603762E Sensor and Guidance Technology…………………………………………………………………………………… 272 50 0603763E Marine Technology………………………………………………………………………………………………… 305 51 0603764E Land Warfare Technology……………………………………………………………………………………………