Rethinking Early Ryukyuan History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Has Still Yet to Recognize Ryukyu/Okinawan Peoples

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan Prepared for 128th Session, Geneva, 2 March - 27 March, 2020 Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. II. Introduction The nation of Japan has made some significant strides in addressing historical issues of marginalization and discrimination against the Ainu Peoples. However, Japan has not made the same effort to address such issues regarding the Ryukyu Peoples. Both Peoples have been subject to historical injustices such as suppression of cultural practices and language, removal from land, and discrimination. Today, Ainu individuals continue to suffer greater rates of discrimination, poverty and lower rates of academic success compared to non-Ainu Japanese citizens. Furthermore, the dialogue between the government of Japan and the Ainu Peoples continues to be lacking. The Ryukyu Peoples continue to not be recognized as Indigenous by the Japanese government and face the nonconsensual use of their traditional lands by the United States military. -

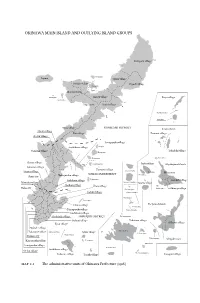

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Procedure for Marrying Japanese in Okinawa

Procedure for Marrying Japanese in Okinawa Affidavit of Competency to Marry (Required Document for marriage in Japan): Legal will assist with completion and endorsement of Affidavit of Competency to Marry for the service member. Translations: Have Affidavit of Competency to Marry Translated into Japanese. Translate Birth Certificate into Japanese or use a Passport. Complete Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage) in Japanese. - This form can be obtained from any City Hall office in Japan. - Two witnesses, 20 years of age or older are required. If they are not Japanese, they must provide proof of citizenship in the form of a Birth Certificate with translation or Passport. City Hall Office: Must go to City Hall where fiancée’s address is registered or where Koseki (Family Tree) is filed Bring the following: Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage) Original documents: Birth Certificate or Passports for the service member. Affidavit of Competency to Marry for the service member. Translated Affidavit of Competency to Marry. Translated Birth Certificate. Copies of witnesses citizenship documents and translations (if applicable). Another form of picture ID. Koseki Tohon. - City hall officials register marriage and issue Marriage Certificate. - Large certificate (A3) has witness names on it (associated costs). - Small certificate (B4) (associated costs). Translation Office: Translate marriage certificate into English (must be “official English translation”). Personnel Office (IPAC): Present Marriage Certificate with translation. Bring all the necessary documents to IPAC for your new spouse to acquire military I.D card. Please call IPAC ID section at 645-4038/5742 for more information. Version 2. Location: Building 5717 Camp Foster, down the hill from the Naval Hospital. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Genetic Lineage of the Amami Islanders Inferred from Classical Genetic Markers

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic lineage of the Amami islanders inferred from classical genetic markers Yuri Nishikawa and Takafumi Ishida Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence: Yuri Nishikawa, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. E-mail address: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The peopling of mainland Japan and Okinawa has been gradually unveiled in the recent years, but previous anthropological studies dealing people in the Amami islands, located between mainland Japan and Okinawa, were less informative because of the lack of genetic data. In this study, we collected DNAs from 104 subjects in two of the Amami islands, Amami-Oshima island and Kikai island, and analyzed the D-loop region of mtDNA, four Y-STRs and four autosomal nonsynonymous SNPs to clarify the genetic structure of the Amami islanders comparing with peoples in Okinawa, mainland Japan and other regions in East Asia. -

Restoration of the Native Species to Amami Oshima Island

alien species in Amami Oshima Island In addition to the Small Indian mongoose, many other alien species (e.g., feral cats, feral goats, black rats and the Lanceleaf tickseed) have become established on Amami Oshima. Please be sure never to leave behind alien species in the wild nor let them escape. Feral cat Feral goat Black rat Lanceleaf tickseed ● Alien species of Amami Islands HP http://kyushu.env.go.jp/naha/wildlife/data/130902aa.pdf We ask for your cooperation in The mongoose eradication project activity of Amami Mongoose Busters in Amami Oshima The Amami Mongoose Busters, which was formed in 2005, has continued its efforts to eradicate mongooses with the support of people in the island and researchers. We ask for your continued onservation of a precious understanding and support of the mongoose control project as C well as the Amami Mongoose Busters. ecosystem in ■ Amami Mongoose Busters Blog http://amb.amamin.jp/ ■ Amami Mongoose Busters Facebook Amami Oshima Island https://www.facebook.com/amamimongoosebusters March 2014 Amami Wildlife Conservation Center, Published by: Ministry of the Environment, Japan Naha Nature Conservation Office, 551 Koshinohata, Ongachi, Yamato-son, Oshima-gun, Ministry of the Environment, Japan Kagoshima 894-3104 TEL:+81-997-55-8620 Okinawa Tsukansha Building 4F, 5-21 Yamashita-cho, Japan Wildlife Research Center, Naha-shi, Okinawa 900-0027 Amami Ooshima Division (Amami Mongoose Busters) 1385-2 Naze, Uragami,Amami-City, Kagoshima 894-0008 TEL:+81-997-58-4013 Edited by : Japan Wildlife Research Center FOR ALL THE LIFE ON EARTH Design : artpost inc. Photos : Mamoru Tsuneda, Teruho Abe, Yoshihito Goto, Kazuki Yamamuro, Biodiversity Ryuta Yoshihara, Japan Wildlife Research Center Animals and plants Habu snake Protobothrops flavoviridis This poisonous snake is found on Amami Oshima, Tokunoshima, Okinawa in Amami Oshima Island Island, and other several neighboring small islands. -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

Sino-US Relations and Ulysses S. Grant's Mediation

Looking for a Friend: Sino-U.S. Relations and Ulysses S. Grant’s Mediation in the Ryukyu/Liuqiu 琉球 Dispute of 1879 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad Michael Berry Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Christopher A. Reed, Advisor Robert J. McMahon Ying Zhang Copyright by Chad Michael Berry 2014 Abstract In March 1879, Japan announced the end of the Ryukyu (Liuqiu) Kingdom and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in its place. For the previous 250 years, Ryukyu had been a quasi-independent tribute-sending state to Japan and China. Following the arrival of Western imperialism to East Asia in the 19th century, Japan reacted to the changing international situation by adopting Western legal standards and clarifying its borders in frontier areas such as the Ryukyu Islands. China protested Japanese actions in Ryukyu, though Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) leaders were not willing to go to war over the islands. Instead, Qing leaders such as Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) and Prince Gong (1833-1898) sought to resolve the dispute through diplomatic means, including appeals to international law, rousing global public opinion against Japan, and, most significantly, requesting the mediation of the United States and former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). Initially, China hoped Grant’s mediation would lead to a restoration of the previous arrangement of Ryukyu being a dually subordinate kingdom to China and Japan. In later negotiations, China sought a three-way division of the islands among China, Japan, and Ryukyu. -

K=O0 I. SONG- Part I INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS Mitsugu Sakihara

~1ASAT6 . MAISt;1 -- 1DMO¥ffiHI -KUROKAWA MINJ!K=o0 I. SONG- Part I INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS Mitsugu Sakihara Ryukyuan Resources at the University of Hawaii Okinawan Studies in the United St9-tes During the 1970s RYUKYUAN RESOURCES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII Introduction The resources for Ryukyuan studies at the University of Hawaii, reportedly the best outside of Japan, have attracted many scholars from Japan and other countries to Hawaii for research. For such study Ryukyu: A Bibliographical Guide to Okinawan Studies (1963) and Ryukyuan Research Resources at the University of Hawaii (1965), both by the late Dr. Shunzo Sakamaki, have served as the best intro duction. However, both books have long been out of print and are not now generally available. According to Ryukyuan Research Resources at the University of Hawaii, as of 1965, holdings totalled 4,197 titles including 3,594 titles of books and documents and 603 titles on microfilm. Annual additions for the past fifteen years, however, have increased the number considerably. The nucleus of the holdings is the Hawley Collection, supplemented by the books personally donated by Dro Shunzo Sakamaki, the Satsuma Collection, and recent acquisitions by the University of Hawaii. The total should be well over 5,000 titles. Hawley Collection The Hawley Collection represents the lifetime work of Mr. Frank Hawley, an English journalist and a well-known bibliophile who resided in Japan for more than 30 yearso When Hawley passed away in the winter of 1961 in Kyoto, Dr. Sakamaki, who happened 1 utsu no shi oyobi jo" [Song to chastize Ryukyu with preface], com posed by Priest Nanpo with the intention of justifying the expedition against Ryukyu in 1609 and of stimulating the morale of the troops. -

Recent Developments in Japan-China Relations - Basic Facts on the Senkaku Islands and the Recent Incident

Recent Developments in Japan-China Relations - Basic Facts on the Senkaku Islands and the Recent Incident - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan October 2010 1 Senkaku Islands ◦ Location ◦ The Basic Facts of the Senkaku Islands Obstruction of the execution of official duty by a Chinese fishing trawler (September 7, 2010) Recent Developments in Japan-China Relations Japan’s Position (Statement by MOFA Press Secretary on September 25 2010) 2 China 330km Uotsuri-Shima Okinawa 170km 410km Japan 170km Taiwan Ishigaki-Shima East China Sea Main island of Okinawa Ishigaki-Shima Kuba-Shima Taisho-To About 27km About Uotsuri-Shima 110km Kitako-Shima About 5km Minamiko-Shima ◦ From 1885 on, the Senkaku Islands had been thoroughly surveyed by the Government of Japan through the agencies of Okinawa Prefecture and by way of other methods. Through these surveys, it was confirmed that the Senkaku Islands had been uninhabited and showed no trace of having been under the control of China. Based on this confirmation, the Government of Japan made a Cabinet Decision on 14 January 1895 to erect a marker on the Islands to formally incorporate the Senkaku Islands into the territory of Japan. ◦ Since then, the Senkaku Islands have continuously remained as an integral part of the Nansei Shoto Islands which are the territory of Japan. These islands were neither part of Taiwan nor part of the Pescadores Islands which were ceded to Japan from the Qing Dynasty of China in accordance with Article II of the Treaty of Shimonoseki which came into effect in May of 1895. ◦ Accordingly, the Senkaku Islands are not included in the territory which Japan renounced under Article II of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. -

Amami Island Religion - Historical Dynamics of the Islanders’ Spirit - Megumi TAKARABE and Akira NISHIMURA

KAWAI, K., TERADA, R. and KUWAHARA, S. (eds): The Islands of Kagoshima Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands, 15 March 2013 Chapter 3 Amami Island Religion - Historical Dynamics of the Islanders’ Spirit - Megumi TAKARABE and Akira NISHIMURA 1. Introduction into “aman’yu” (Amami period),” “aji’yu” (Lords enerally speaking, Japan’s indigenous Shinto period), “nahan’yu” (Ryukyu kingdom period), Gand exogenous Buddhism represent the ma- “yamaton’yu” (Shimadzu controlling period) and jority religions in Japan. These religions have been “america’yu” (American controlling period). Re- recognized as the spiritual pillars of the Japanese. cords are only available from the Naha period on- When compared with the history of religion in Ja- wards and it was the Ryukyu-dominated Amami Is- pan, “Amami Island religion” can be considered lands that welcomed the first unified regime. There unique for its history as well as for its distant loca- are two theories concerning this period, one that it tion from mainland Japan. This is because the reli- began in 1266 (SAKAGUCHI 1921, NOBORI 1949) and gious culture which has existed in various parts of one that it began in 1440 (Richo Jitsuroku). The the Amami Islands comprise a long-standing spiri- latter theory is currently the prevailing view. Ac- tual pillar of the islanders. In other words, the Ama- cordingly, the Amami Islands in the Naha period mi Islands have enjoyed a religious culture of the are said to have lasted for approximately 170 years Ryukyu legacy rather than that of mainland Japan. from 1440 to 1609. This religious culture informs the spiritual base of During the Naha period and the reign of the the Amami Islands today.