Montreal's Chinese Diaspora Breaks Out/In Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

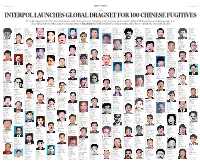

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Montreal, Québec

st BOOK BY BOOK BY DECEMBER 31 DECEMBER 31st AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE RESERVATION FORM: (Please Print) TOUR CODE: 18NAL0629/UArizona Enclosed is my deposit for $ ______________ ($500 per person) to hold __________ place(s) on the Montreal Jazz Fest Excursion departing on June 29, 2018. Cost is $2,595 per person, based on double occupancy. (Currently, subject to change) Final payment due date is March 26, 2018. All final payments are required to be made by check or money order only. I would like to charge my deposit to my credit card: oMasterCard oVisa oDiscover oAmerican Express Name on Card _____________________________________________________________________________ Card Number ______________________________________________ EXP_______________CVN_________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME FOR NAME BADGE IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE: 1)____________________________________ 2)_____________________________________ STREET ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________ CITY:_______________________________________STATE:_____________ZIP:___________________ PHONE NUMBERS: HOME: ( )______________________ OFFICE: ( )_____________________ 1111 N. Cherry Avenue AZ 85721 Tucson, PHOTO CREDITS: Classic Escapes; © Festival International de Jazz de Montréal; -

TV Show Knows What's in Your Fridge Is Food for Thought

16 | Wednesday, June 17, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY YOUTH ometimes you have to travel didn’t enjoy traditional Chinese to appreciate your own. music that much until he pursued his Sometimes, waking up in a music studies in the United States. foreign land gives you a pre- When leaving China, he took with Scious insight into your own country. him the hulusi, a kind of Chinese Fang Songping is a musician and wind instrument made from a has traveled but when he was at gourd, and played it recreationally home with his pipa-player father, in the college. The exotic sound of Fang Jinlong, he preferred Western the instrument won him lots of fans rock. and requests to perform on stage. It was hulusi, the gourd-like Then he started researching about instrument, that really changed his traditional Chinese music and com- life. He happened to bring it to Los bining elements of it into his own Angeles, while studying music there. compositions. In 2015, he returned His classmates were fascinated to China and started his career as an when he played music with it, and a indie musician. new horizon opened up before him. Now, Fang Songping works as the According to a recent report on music director of a popular reality traditional Chinese music, young show, Gems of Chinese Poetry, Chinese people are turning their which centers on traditional Chi- attention to traditional arts. More nese arts, such as poetry, music, and more are listening to traditional dance and paintings. He composed Chinese music. eight original instrumental pieces, The report was released on June inspired by traditional Chinese cul- 2, under the guidance of the China ture, like music, chess, calligraphy Association of Performing Arts, by and paintings. -

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart 王⾠威 编辑 Version 1 Compiled by WANG Chenwei 2021-04-29 26-Musician Orchestra for SCO Composer Workshop 2022 [email protected] Recommendedabbreviations ofinstrumentnamesareshown DadiinF DadiinG DadiinA QudiinBb QudiinC QudiinD QudiinEb QudiinE BangdiinF BangdiinG BangdiinA XiaodiinBb XiaodiinC XiaodiinD insquarebrackets ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ 2Di ‹ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ [Di] ° & ˙ (Transverseflute) & ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ¢ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ b˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ s˙ounds 8va -DiplayerscandoubleontheXiaoinForG(samerangeasDadiinForG) -ThischartnotatesmiddleCasC4,oneoctavehigherasC5etc. #w -WhileearlycompositionsmightdesignateeachplayerasBangdi,QudiorDadi, -8va=octavehigher,8vb=octavelower,15ma=2octaveshigher 1Gaoyin-Sheng composersareactuallyfreetochangeDiduringthepiece. -PleaseusethetrebleclefforZhonghupartscores [GYSh] ° -Composerscouldwriteonestaffperplayer,e.g.Di1,Di2andspecifywhentousewhichtypeofDi; -Pleaseusethe8vbtrebleclefforZhongyin-Sheng, (Sopranomouthorgan) & ifthekeyofDiislefttotheplayers'discretion,specifyatleastwhetherthepitchshould Zhongyin-GuanandZhongruanpartscores w soundasnotatedor8va. w -Composerscanrequestforamembranelesssound(withoutdimo). 1Zhongyin-Sheng -WhiletheDadiandQudicanplayanother3semitonesabovethestatedrange, [ZYSh] theycanonlybeplayedforcefullyandthetimbreispoor. -ForeachkeyofDi,thesemitoneabovethelowestpitch(e.g.Eb4ontheDadiinG)sounds (Altomouthorgan) & w verymuffledduetothehalf-holefingeringandisunsuitableforloudplaying. 低⼋度发⾳ ‹ -Allinstrumentsdonotusetransposednotationotherthantranspositionsattheoctave. -

Pipa Virtuoso Fang Leads WSO Back to Classics

Print Story - canada.com network Page 1 of 2 Saturday » February 16 » 2008 Pipa virtuoso Fang leads WSO back to classics Ted Shaw The Windsor Star Sunday, February 10, 2008 It was back to the classics Saturday for the Windsor Symphony Orchestra, but the spirit of the recent Windsor Canadian Music Festival lingered in a contemporary Chinese work. WCMF unveils new Canadian compositions with often unconventional or experimental instrumentation. While Tan Dun's Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa is not Canadian, it was performed by Montreal-based pipa virtuoso, Liu Fang, and called upon the string players to beat the tops of their instruments at times and shout Chinese words. It was particularly striking in the context of the rest of the program of works written before the first decade of the 19th century. CREDIT: Scott Webster, The Windsor Star Pipa player Liu Fang performs with the Windsor Chinese-born Tan Dun is the Grammy and Oscar-winning Symphony Orchestra Saturday night. composer of such film soundtracks as Hero and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. His use of traditional Chinese instruments in the context of Western musical idioms has earned him a special place among the new generation of composers living in the United States. His pipa concerto is classically structured and borrows liberally from the concerto tradition, including having a cadenza. But the instrument itself is decidedly exotic in sound. Pear-shaped like a lute but lacking a sound hole, the pipa has a percussive quality and is plucked with plectrums, although there is a considerable amount of chord work and strumming involved, as well. -

Three Millennia of Tonewood Knowledge in Chinese Guqin Tradition: Science, Culture, Value, and Relevance for Western Lutherie

Savart Journal Article 1 Three millennia of tonewood knowledge in Chinese guqin tradition: science, culture, value, and relevance for Western lutherie WENJIE CAI1,2 AND HWAN-CHING TAI3 Abstract—The qin, also called guqin, is the most highly valued musical instrument in the culture of Chinese literati. Chinese people have been making guqin for over three thousand years, accumulating much lutherie knowledge under this uninterrupted tradition. In addition to being rare antiques and symbolic cultural objects, it is also widely believed that the sound of Chinese guqin improves gradually with age, maturing over hundreds of years. As such, the status and value of antique guqin in Chinese culture are comparable to those of antique Italian violins in Western culture. For guqin, the supposed acoustic improvement is generally attributed to the effects of wood aging. Ancient Chinese scholars have long discussed how and why aging improves the tone. When aged tonewood was not available, they resorted to various artificial means to accelerate wood aging, including chemical treatments. The cumulative experience of Chinese guqin makers represent a valuable source of tonewood knowledge, because they give us important clues on how to investigate long-term wood changes using modern research tools. In this review, we translated and annotated tonewood knowledge in ancient Chinese books, comparing them with conventional tonewood knowledge in Europe and recent scientific research. This retrospective analysis hopes to highlight the practical value of Chinese lutherie knowledge for 21st-century instrument makers. I. INTRODUCTION In Western musical tradition, the most valuable musical instruments belong to the violin family, especially antique instruments made in Cremona, Italy. -

Mark Laver Jazzvertising

Jazzvertising: Music, Marketing, and Meaning by Mark Laver A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Mark Laver 2011 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-78257-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-78257-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. -

Video Competition 2020

VIDEO COMPETITION 2020 ABOUT: The United States International Music Competition is organized by the United States International Music Foundation affiliated with the Chinese Music Teachers’ Association of Northern California, a non-profit organization. This competition provides young musicians with an opportunity to exhibit their talents and reward their hard work, as well as to encourage them to appreciate cross-cultural exchanges . ELIGIBILITY: Contestants of all nationalities.No Age Limit. Past First Place winners may not compete in an age group that they have won previously. However, they may elect to compete in another age-appropriate group. INSTRUMENT CATEGORIES: Piano (Solo, Duet, and Concerto), Violin, Viola, Cello, Classical Chamber Ensembles (Western Instruments), Vocal (Solo and Ensemble), Marimba, and Traditional Chinese Instruments categories are held annually. Harp and Classical Guitar are also included in the 2020 competition categories. AGE GROUPS: Eligibility for each group will be determined by the contestant’s age as of June 1, 2020. Each instrument category has different age groups. Category & Piano Violin Viola Cello Vocal Age groups A Age 9 or under Age 9 or under Age 14 or under Age 11 or under Age 9 or under B Age 11 or under Age 13 or under Age 18 or under Age 14 or under Age 12 or under C Age 14 or under Age 18 or under Age 19 or above Age 18 or under Age 14 or under D Age 18 or under Age 19 or above Age 19 or above Age 18 or under E Age 19 or above Age 19 or above Piano Duet Category -

Ming Wang Whilst Studying Painting in the 1970'S, I Began Learning Chinese Music

A review of my experiences, and criticism of the music exchange projects Ming Wang Whilst studying painting in the 1970's, I began learning Chinese music. This was introduced to Taiwan from mainland China after the Chinese Civil War in 1949. Hence my first “great love” of this music, but it was extremely difficult to learn. Because of the political situation with mainland China the culture of this music was totally separated from its roots. We had very limited teaching material and literature, had no systematic pedagogical methodology. We were young and passionate at the time and wanted to find a solution, a future for this music. The introduction of Western Modernism was a great hope for us then, as it has often been in the history of China over the last 150 years. While my music friends founded the first revolutionary ensemble with Chinese instruments, to specialize in Taiwanese and Western contemporary music, I decided to study composition in Europe; to learn the western avant-garde, so that we could enrich Chinese music. With this goal in mind, since 1996 – during my studies - I have initiated or participated in several exchange projects between Austria and Taiwan. I try not only to present new european music in Taiwan, but also to introduce Taiwanese musicians, Chinese instruments and music to Europe. Twenty years later in the age of globalisation, I often think about whether such exchange projects really make artistic sense, or whether we have gradually lost our ideals in the workings of the music business. With a few concrete examples, I would like to give a review of my years of experience with the music exchange projects, and offer this topic for discussion. -

Download Article (PDF)

International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2015) Birth and Research of Erhu Concerto Jindi Zhang Art College, Shandong University, Weihai, 264209, China Keywords: Erhu; Concerto Abstract. Erhu concerto is a type of music which was born under integration of Chinese and western cultures. It is one of the most typical solo concertos in Chinese national musical instruments. Since the establishment of new China, Erhu concerto has developed rapidly. It gained different development in four historical periods: before the reform and opening-up, 1980s, 1990s and the 21st century. Erhu concerto generates significant influence on development of Erhu music and occupies an important position in development history of Erhu music. Birth of Erhu concerto Since the 20th century, Erhu concerto born under multi-culture development is a kind of new music expression form. It derives from European music, but is different from European music. In 1930s, Erhu divertimento The Death of Yang Yuhuan created by Russian Jewish composer AapoHABUiajiyMOB (1894-1965) consists of 6 songs and adopts the form of Erhu and symphony orchestra. This is the earliest Erhu concerto recorded in the history and originated from the melody of self-created song Evening Scene of Ynag Yuhuan in 1936. In Yearbook of Chinese Music (2002), Mr. Zheng Tisi said in his memoirs that, this works was performed in public in Shanghai Lanxin Theater. The band was Shanghai Municipal Council Orchestra. The outstanding folk music performer Mr. Wei Zhonglei took charge of Erhu solo, and the composer was responsible for commanding. Such manifestation pattern of Erhu music was certain far-sighted in the development of world music and also reflected world culture had walked out of European cultural circle and went to other developing countries. -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for Degree of Doct

Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2021 Copyright of Mahasarakham University เทคนิคการบรรเลงของซอบา่ นหู ในภาคเหนือ ของประเทศจีน วิทยานิพนธ์ ของ Yun Meng เสนอต่อมหาวทิ ยาลยั มหาสารคาม เพื่อเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตร ปริญญาปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาดุริยางคศิลป์ กุมภาพันธ์ 2564 ลิขสิทธ์ิเป็นของมหาวทิ ยาลยั มหาสารคาม Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (Music) February 2021 Copyright of Mahasarakham University The examining committee has unanimously approved this Thesis, submitted by Mr. Yun Meng , as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Music at Mahasarakham University Examining Committee Chairman (Assoc. Prof. Wiboon Trakulhun , Ph.D.) Advisor (Asst. Prof. Sayam Juangprakhon , Ph.D.) Committee (Asst. Prof. Peerapong Sensai , Ph.D.) Committee (Asst. Prof. Khomkrit Karin , Ph.D.) Committee (Assoc. Prof. Phiphat Sornyai ) Mahasarakham University has granted approval to accept this Thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Music (Asst. Prof. Khomkrit Karin , Ph.D.) (Assoc. Prof. Krit Chaimoon , Ph.D.) Dean of College of Music Dean of Graduate School D ABSTRACT TITLE Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China AUTHOR Yun Meng ADVISORS Assistant Professor Sayam Juangprakhon , Ph.D. DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy MAJOR Music UNIVERSITY Mahasarakham University YEAR 2021 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to study the technique and application of Banhu. The purposes of this study are: 1) to examine the history of Banhu in northern China; 2) to classify banhu according to the difficulty of his playing skills; 3) to analyze selected music examples.