Mark Laver Jazzvertising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montreal, Québec

st BOOK BY BOOK BY DECEMBER 31 DECEMBER 31st AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE RESERVATION FORM: (Please Print) TOUR CODE: 18NAL0629/UArizona Enclosed is my deposit for $ ______________ ($500 per person) to hold __________ place(s) on the Montreal Jazz Fest Excursion departing on June 29, 2018. Cost is $2,595 per person, based on double occupancy. (Currently, subject to change) Final payment due date is March 26, 2018. All final payments are required to be made by check or money order only. I would like to charge my deposit to my credit card: oMasterCard oVisa oDiscover oAmerican Express Name on Card _____________________________________________________________________________ Card Number ______________________________________________ EXP_______________CVN_________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME FOR NAME BADGE IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE: 1)____________________________________ 2)_____________________________________ STREET ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________ CITY:_______________________________________STATE:_____________ZIP:___________________ PHONE NUMBERS: HOME: ( )______________________ OFFICE: ( )_____________________ 1111 N. Cherry Avenue AZ 85721 Tucson, PHOTO CREDITS: Classic Escapes; © Festival International de Jazz de Montréal; -

RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector's Series”

RCA Discography Part 28 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector’s Series” The LCT series was releases in the Long Play format of material that was previously released only on 78 RPM records. The series was billed as the Collector’s Treasury Series. LCT 1 – Composers’ Favorite Intepretations - Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra [195?] Rosca: Recondita Amonia – Enrico Caruso/Madama Butterfly, Entrance of Butterfly – G. Farrar/Louise: Depuis Le Jour – M. Garden/Louise: Depuis Longtemps j’Habitais – E Johnson/Tosca: Vissi D’Arte – M. Jeritza/Der Rosenkavailier Da Geht ER Hin and Ich Werd Jetzt in Die Kirchen Geh’n – L Lehmann/Otello: Morte d’Otello – F. Tamagno LCT 2 – Caruso Sings Light Music – Enrico Caruso and Mischa Elman [195?] O Sole Mio/The Lost Chord/For You Alone/Ave Maria (Largo From "Xerxes")/Because/Élégie/Sei Morta Nella Vita Mia LCT 3 – Boris Goudnoff (Moussorgsky) – Feodor Chalipin, Albert Coates and Orchestra [1950] Coronation Scene/Ah, I Am Suffocating (Clock Scene)/I Have Attained The Highest Power/Prayer Of Boris/Death Of Boris LCT 4 LCT 5- Hamlet (Shakespeare) – Laurence Olivier with Philharmonia Orchestra [1950] O That This Too, Too Solid Flesh/Funeral March/To Be Or Not To Be/How Long Hast Thou Been Gravemaker/Speak The Speech/The Play Scene LCT 6 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in G Minor Op. 63 (Prokofieff) – Jascha Heifetz and Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra [1950] LCT 7 – Haydn Symphony in G Major – Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra [195?] LCT 8 LCT 9 LCT 10 –Rosa Ponselle in Opera and Song – Rosa Ponselle [195?] La Vestale: Tu Che Invoco; O Nume Tutelar, By Spontini/Otello: Salce! Salce! (Willow Song); Ave Maria, By Verdi/Ave Maria, By Schubert/Home, Sweet Home, By Bishop LCT 11 – Sir Harry Lauder Favorites – Harry Lauder [195?] Romin' In The Gloamin'/Soosie Maclean/A Wee Deoch An' Doris/Breakfast In Bed On Sunday Morning/When I Met Mackay/Scotch Memories LCT 12 – Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. -

School Trustees Won't Run Again

h amp season t on the P1soor Smashed Standard reporter has a. Local square dancing club Speedway fans witness go at a roster spot with with dwindling numbers looks metal carnage on final ’, 5 the second-year River for younger recruits stock car racing day , Kings\NIEWS A5 \COMMUNlrY BI \SPORTS B4 A \ -0 -0 $1.OO PLUS 74 GST -vl - ($1.10 plus 813 GST outside of the Terrace area) -00 -- , h I, School trustees won’t run again By DUSTIN QUEZADA that frightens two-term Terrace trustee Hal Stead- elected. 2 teacher’s strike.” A DIFFICULT three years for school district 82 ham, who’s undecided but leaning toward seeking Other incumbent Terrace trustees include Diana Kitimat’s King said a strike should deter candi- have left many incumbent board trustees choosing re-election. Penner and Nicole Bingham-Georgelin. dates from stepping forward. 0 not to run again in November. Steadham said he wouldn’t want to walk away Penner, who has served two terms, is undecided. “I’ve been through two previous strikes and ’ Of the nine current trustees, two have decided to with the problems that face the board. Penner-cited a combination of work constrainsts it’s part of what’s necessary to negotiate an agree- run again, two are undecided, four are not seeking “If I knew the majority were coming back, impor- and a frustration with the government. ment,” King said. “The decisions are out of our re-election and one didn’t return phone calls. tant decisions would be made,” Steadham said. -

Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1947 Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947)." , (1947). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/181 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. XUQfr JNftr o 10 I s vation Army Band, has retired, after an AARON COPLAND’S Third Symphony unbroken record of sixty-four years’ serv- and Ernest Bloch’s Second Quartet have ice as Bandmaster in the Salvation Army. won the Award of the Music Critics Cir- cle of New York as the outstanding music American orchestral and chamber THE SALZBURG FESTI- BEGINNERS heard for the first time in New York VAL, which opened on PIANO during the past season. YOUNG July 31, witnessed an im- FOB portant break with tra- JOHN ALDEN CARPEN- dition when on August TER, widely known con- 6 the world premiere of KEYBOARD TOWN temporary American Gottfried von Einem’s composer, has been opera, “Danton’s Tod,” By Louise Robyn awarded the 1947 Gold was produced. -

Second Annual Report

THE CANADA CQUNCIL Second Annual Report TO MARCH 31, 1959 THE CANADA COUNCIL Patfo”: June 30, 1959 The Right Hon. John G. Diefenbaker, P.C., M.P. Prime Minister of Canada Ottawa, Ontario Sir: 1 have the honour to transmit herewith the Annual Report of The Canada Council as required bg section 23 of The Canada Council Act (5-6 Elizabeth II, 1957, Chap. 3) for the fiscal year ending March. 31, 1959. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, Chairman TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction . 1 PART ONE: ORGANIZATION Meetings , . Publications . The Staff . Co-operating Agencies . The Kingston Conference . Help given the Cou&l . PART Two: UNIVERSITY CAPITAL GKANTS Eligibility . 9 Grants Made’ : : : : : : : : : : : . 10 PARTTEREE: ENDOWMENTFUND Objects and Powers . 11 Scholarship and FeIlowship Scheme . 11 Grants to Organizations . 14 Other Contributions . 18 PART Fou~: A POLIcY FOR TEE ARTS New Music from the Composers . 20 The Canadian Music Centre . 21 Commissions for Dramatists . 21 Purchase Awards for Painters . 22 Commissions for Sculptors . 22 Assistance to Organizations Presenting the Arts 23 Organizations Presenting the Visual Arts 23 Orchestras . - . 24 Summer Concerts . 25 Assistance to Choirs . 25 The Theatre . 26 Dominion Drama Festival . 27 Review of Arts Policies . 27 Some Problems of Creative Ar&ts 28 Touring Organizations . opp. p. 28 Taxation on Creative Work . 30 Aid to Publication . 31 Aid to Periodicals . 31 Ballet Survey . 32 Confederation Centenniai : : 1 33 A National Theatre . 33 PART FIYE: INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL RELATIONS Objective .......... 36 Cultural exchanges -‘Orga&ations ......... 36 Canada Council Lectureships ........... 36 Visiting Lecturers .............. 37 Individuals ................ 37 TABLE OF CONTENTS- (Continued) Page Senior Non-Resident Fellowships .......... -

CBC Times 500709.PDF

0"'''n ... - ... "'''' ......."'" 0:0:<... o~'" or 7.: ...... ~ .... ~ ... PRAIRIE REGI '"',.,... SCHEDULE ... July 9 -Z5, 195 '" Issued Each Week by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation VOLUME III No. 28 ISSUED AT WINNIPEG. JUNE 30 Sc PER COPY $1.00 PER YEAR This Week: Winnipeg Strings (Page 2) * Canadian Family Tree (Page 3) Korda On* Movies (Page 4) * Shaw's Village Wooing (Page 5) Lo~t'cr Basin* Street (Page 8) N the garden of a recently-flooded* Winnipeg I home, a CDC Special Events crew is recording an item for Saturday Magazine (Saturday~' 2:03 1:03 p.m.), in this week's cOver picture. Left to right arc: Bon WILSON and NORMAN MCnAIN (with microphone), cnc annoum..'CTS; MISS CATU .,:HINE MAcIvl::Il. CBe talks producer; VINCENT ~lc~IAJION> cac operator; C. C. GUNNIKC. CBe news editor (standing) and JACK \VllITEHOUSf;' owner of the flooded home. *** Special Events "Showing one end of Canada to the other and hoth ends to the middle:' That's how A. E. Powley of Toronto sums up the idea behind his work in planning and arran~ ing special ('vents hroadcasts for the CBC. The actuality broadcast, he points out, is one of radio's nni(lue talents. The CBC exploits it cxtensively during the summer more than in anv other season -"to seek out and bring to the Canadian audience by means of on-th£O-spot description happeninJ(s and customs and plal.'(,'S that go to make up the Canadian scene. Actuality programs (most important of which is Saturday Magazine on the Trans-Canada network) Powley says are based on the idea that the Cana dian scene is so wide and varied as to be full of eRe Saturday Magazine materials of interest to listeners across the country. -

Barcelona Cultura Nº 3

EDITORIAL Sumari El debat sobre la conservació de les restes maig-juny 2002 Junta de Govern arqueològiques aparegudes al subsòl de l'antic mercat Ferran Mascarell del Born ha posat en relleu el desconeixement general president Marina Subirats que hi ha sobre els procediments d'intervenció en vicepresidenta aquests casos i l'aparell legal en què es fonamenten. La conservació de les restes Jordi Hereu arqueològiques 4 Ernest Maragall En l'article molt esclaridor que publiquem en aquest Maravillas Rojo Jaume Ciurana número, el director del Museu d'Història de la Ciutat, Joana Ortega Entrevista a Gabriel Planella 8 Santiago Fisas Antoni Nicolau, que és un dels membres de la Jordi Portabella Imma Mayol comissió tècnica que elabora els informes valoratius Sis setmanes de poesia, sis 10 Blanca Barbero Júlia Pérez sobre la importància de les troballes, situa la qüestió i Any Verdaguer 11 Montserrat Mascaró aporta una valuosa informació sobre els criteris i la secretària delegada Lluís Salvat metodologia emprats per objectivar al màxim possible Una ciutat de festival 12 interventor delegat el treball dels tècnics. És un assumpte d'alt d'interès, perquè es tracta de la renovació del teixit urbà i del Art emergent 13 respecte a la història, que s'enfoca de maneres molt Setmana digital 14 Vista general del carrer diverses segons els casos i els països, fins al punt que del Bonaire i l'entrada del Palau de Pere Montoliu. la Unió Europea està començant a treballar amb Excavació del Born, 2002 Biblioteques: més que llibres Foto MHCB l'objectiu de donar uns criteris i unes pautes comunes 15 Equip editorial d'actuació. -

Senate Approves Graduating Students' Right to Choose Name of Degree

Vol. 16 No. 17 February 13, 1992 Degree nomenclature issue sparked by request for Mistress of Arts Senate approves graduating students' right to choose name of degree Claudie Solar, the Advisor to the Rec a motion at last Friday's Senate meeting tor on the Status of Women, told Senate to allow students to choose the name of nna Varrica that universities across Canada were their degrees. watching Concordia to see what it "Language can be a vehicle for bias, would do. And what it did was approve denoting heterosexism and racism," said Solar. That bias may be removed and graduating students may eventually be able to choose between a Bachelor's de The spills of the Fifth Annual Corey Cup gree or a 'baccalaureate,' the Master's degree or the 'magisteriate.' Doctoral at the Forum bring thrills but no victory degrees will remain unchanged. The Senate Ad Hoc Committee on De gree Nomenclature was established in PHOTO: Jonas Papaurelis April 1990 in response to student Carolyn Gammon's request for a The Fifth Annual Corey Cup hockey game Mistress of Arts instead of a Master of between Concordia and McGill resurrected Arts after completing the requirements the cross-town rivalry of the two teams. for her degree. The Committee was Though Concordia put in a valiant effort, com chaired by Religion Professor Michael ing from behind in the second period with Oppenheim. goals scored by Steve Salhany and Stephane Therrien, McGill rallied in the third to take the The Committee unanimously voted match 4-2. Proceeds from the game went to to deny Gammon's request, but it did the Quebec Society for Disabled Children. -

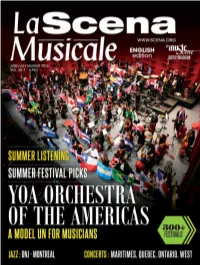

Lsm11-6 Ayout

sm20-7_EN_p01_coverV2_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:55 PM Page 1 RCM_LaScenaMusicale_4c_fp_June+Aug15.qxp_Layoutsm20-7_EN_p02_rcmAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:56 1 2015-05-27PM Page 2 9:33 AM Page 1 2015.16 Terence CONCERT Blanchard SEASON More than 85 classical, jazz, pop, world music, and family concerts to choose from! Koerner Hall / Mazzoleni Concert Hall / Conservatory Theatre Igudesman & Joo Daniel Hope Vilde Frang Jan Lisiecki SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 12 SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 19 416.408.0208 www.performance.rcmusic.ca 273 BLOOR STREET WEST (BLOOR ST. & AVENUE RD.) TORONTO sm20-7_EN_p03_torontosummerAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:57 PM Page 3 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS JUL 16-AUG 9 DANISH STRING KARITA MATTILA QUARTET GARRICK AMERICAN OHLSSON AVANT-GARDE DANILO YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS PÉREZ WITH INGRID FLITER AND MUCH MORE! UNDER 35 YEARS OLD? TICKETS ONLY $20! TORONTOSUMMERMUSIC.COM 416-408-0208 an Ontario government agency un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario sm20-7_EN_p04_TOC_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:58 PM Page 4 VOL 20-7 JUNE/JULY/AUGUST 2015 CONTENTS 10 INDUSTRY NEWS 11 Orchestre National de Jazz - Montréal 12 Jazz Festival Picks 14 Classical Festival Picks 19 Arts Festival Picks 21 Summer Listening GUIDES 22 Canadian Summer Festivals 37 REGIONAL CALENDAR 38 CONCERT PREVIEWS YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS 6 FOUNDING EDITORS PUBLISHER OFFICE MANAGER TRANSLATORS SUBSCRIPTIONS Wah Keung Chan, Philip Anson Wah Keung Chan Brigitte Objois Michèle Duguay, Véronique Frenette, Surface mail subscriptions (Canada) cost EDITOR-IN-CHIEF SUBSCRIPTIONS & DISTRIBUTION Cecilia Grayson, Eric Legault, $33/ yr (taxes included) to cover postage and La Scena Musicale VOL. -

Box # # of Items in Folder Name of Organization

Box # of Name of Organization (note: names that are underlined are filed by the underlined word in alphabetical order) Location # Items in Folder 1 1 Feike Asma. Organ recital. Toronto Toronto 1 ARS NOVA presents Theatre of Early Music presents "Star of Wonder" A Christmas Concert. Knox Presbyterian Church, Ottawa Ottawa. 1 ARS Omnia with Contemporary Music Projects presents The Inspiration of Greece and China. A trans-cultural Toronto contemporary music event. Kings College Circle, University of Toronto. 1 2 ARS Organi. Montreal 1 L'ARMUQ Quebec 1 1 A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 L'Academie Commerciale Catholique de Montreal. Montreal 1 1 L'Academie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 1 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] 2 Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 2 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto 1 2 Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 Acustica International Montreal. Montreal 1 1 John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 1 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto 1 2 Afternoon Concert Series. The Women's Musical Club of Toronto. -

Legacy of the OLYMPIC GAMES in Montreal – an Introduction

3eme Congrès Olympique Canadien Legacy of the OLYMPIC GAMES in Montreal – An Introduction par Michel Guay Association Olympique Canadienne Montréal, 27 avril, 1996 Legacy of the OLYMPIC GAMES in Montreal – An Introduction Introduction Let me first thank the Canadian Olympic Association for this invitation to talk about of the benefits from the Games of the XXI Olympiad held in Montreal in 1976. In addressing you to- day, I have some very mixed feelings. On one hand, I am very proud about the great achievement that resulted from the excellent work of all my colleagues at COJO and the other Canadians that made possible the tremendous great success of 1976. Once, in a while we, the people of C07076, are still boost up by the comments of people like: • Dr. Havelange, president of FIFA, who stated that: "the Montreal Games are still the reference in terms of the quality of the organization" • the Canadian athletes winning a Gold Medal and saying that the Montreal Games were their trigger in their pursuit of excellence, and • the many events that take place and which are almost direct descendant of the Games. But at the same time, I feel like the "Athlete" that has worked very hard to achieve the world's highest level of performance in his sport but is prevented to participate in "his Olympic games" by some event beyond his control! Obviously, you know that I am referring to the negative image of the Montreal Games that is too often presented in relationship with one aspect of the Olympic project, the costs of the Olympic Park installations (Stadium, Swimming Pool and Velodrome) and the political football the whole situation has become since the closing of the Games in August 1976. -

May 1941) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 5-1-1941 Volume 59, Number 05 (May 1941) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 59, Number 05 (May 1941)." , (1941). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/250 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M . N»J " '** fifty jM( * 'H it' » f A f ’\Jf ? I» ***v ASCAP STATES ITS POLICY OF CO-OPERATION WITH ALL MUSIC EDUCATORS, ASSOCIATIONS, AND RELATED GROUPS: music educators, teachers, _, HERE HAS BEEN some misunderstanding upon the part of institutions, and others, music of our members has been withdrawn by ASCAP from use by X to the effect that the copyrighted educational and civic programs. This is not the fact. broadcasters in non-commercial religious, stations (network controlled) will not permit The radio networks and most of the important to be per- by any member of ASCAP, regardless of the nature of the formed on their airwaves, any music composed and presented by a church, school, club, civic group, or music program, even if entirely non-commercial, students or classes.