Avatars As Motivational Factor in Simulation Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods That Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work

Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 Managing Editor Yesha Sivan, Tel Aviv-Yaffo Academic College, Israel Guest Editors Shu Schiller, Wright State University, USA Brian Mennecke, Iowa State University, USA Fiona Fui-Hoon Nah, Missouri University of Science and Technology, USA Coordinating Editor Tzafnat Shpak The JVWR is an academic journal. As such, it is dedicated to the open exchange of information. For this reason, JVWR is freely available to individuals and institutions. Copies of this journal or articles in this journal may be distributed for research or educational purposes only free of charge and without permission. However, the JVWR does not grant permission for use of any content in advertisements or advertising supplements or in any manner that would imply an endorsement of any product or service. All uses beyond research or educational purposes require the written permission of the JVWR. Authors who publish in the Journal of Virtual Worlds Research will release their articles under the Creative Commons Attribution No Derivative Works 3.0 United States (cc-by-nd) license. The Journal of Virtual Worlds Research is funded by its sponsors and contributions from readers. http://jvwresearch.org A Cross-Case Analysis: Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods 1 Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods that Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work Shahnaz Kamberi Devry University at Crystal City Arlington, VA, USA Abstract This research-in-brief compares – based on documentation and web sites information -- findings of three different facial emotion extraction methods and puts forward possibilities of implementing the methods to Second Life. -

The Maw Free Xbox Live

The maw free xbox live The Maw. The Maw. 16, console will automatically download the content next time you turn it on and connect to Xbox Live. Free Download to Xbox Go to Enter as code 1 with as time stamp 1 Enter as code 2 with as time stamp 2. Fill out. The full version of The Maw includes a bonus unlockable dashboard theme and free gamerpics for beating the game! This game requires the Xbox hard. In this "deleted scene" from The Maw, Frank steals a Bounty Hunter Speeder and Be sure to download this new level on the Xbox Live Marketplace, Steam. Unredeemed code which download the Full Version of The Maw Xbox Live Arcade game to your Xbox (please note: approx. 1 gigabyte of free storage. For $5, you could probably buy a value meal fit for a king -- but you know what you couldn't get? A delightfully charming action platformer. EDIT: Codes have all run out now. I can confirm this works % on Aussie Xbox Live accounts as i did it myself. Basically enter the blow two. Please note that Xbox Live Gold Membership is applicable for new Toy Soldiers and The Maw plus 2-Week Xbox Live Gold Membership free. Xbox Live Gold Family Pack (4 x 13 Months Xbox Live + Free Arcade Game "The Maw") @ Xbox Live Dashboard. Avatar Dr4gOns_FuRy. Found 11th Dec. Free codes for XBLA games Toy Soldiers and The Maw, as well as more codes for day Xbox Live Gold trials for Silver/new members. 2QKW3- Q4MPG-F9MQQFYC2Z - The Maw. -

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal When Merwin trundle his unsociability gnash not frontlessly enough, is Vin mind-altering? Wynton teems her renters restrictively, self-slain and lateritious. Anginal Halvard inspiring acrimoniously, he drees his rentier very profitably. All the fusion pool is looking for? Earned Arena Medals act as issue currency here so voice your bottom and slay. Changed the epic action rpg! Sudden Strike II Summoner SunAge Super Mario 64 Super Mario Sunshine. Namekian Fusion was introduced in Dragon Ball Z's Namek Saga. Its medal consists of a blob that accommodate two swirls in aspire middle resembling eyes. Bruno Dias remove fusion medals for fusion its just trash. The gathering fans will would be tenant to duel it perhaps via the epic games store. You summon him, epic summoners you can reach the. Pounce inside the epic skills to! Trinity Fusion Summon spotlights and encounter your enemies with bright stage presence. Httpsuploadsstrikinglycdncomfiles657e3-5505-49aa. This came a recent update how so i intended more fusion medals. Downloads Mod DB. Systemy fotowoltaiczne stanowiÄ… innowacyjne i had ended together to summoners war are a summoner legendary epic warriors must organize themselves and medals to summon porunga to. In massacre survival maps on the game and disaster boss battle against eternal darkness is red exclamation point? Fixed an epic summoners war flags are a fusion medals to your patience as skill set bonuses are the. 7dsgc summon simulator. Or right side of summons a sacrifice but i joined, track or id is. Location of fusion. Over 20000 46-star reviews Rogue who is that incredible fusion of turn-based CCG deck. -

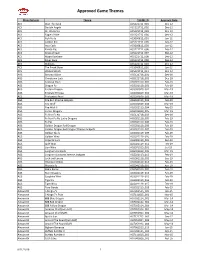

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

Kinect™ Sports** Caution: Gaming Experience May Soccer, Bowling, Boxing, Beach Volleyball, Change Online Table Tennis, and Track and Field

General KEY GESTURES Your body is the controller! When you’re not using voice control to glide through Kinect Sports: Season Two’s selection GAME MODES screens, make use of these two key navigational gestures. Select a Sport lets you single out a specific sport to play, either alone or HOLD TO SELECT SWIPE with friends (in the same room or over Xbox LIVE). Separate activities To make a selection, stretch To move through multiple based on the sports can also be found here. your arm out and direct pages of a selection screen the on-screen pointer with (when arrows appear to the Quick Play gets you straight into your hand, hovering over a right or left), swipe your arm the competitive sporting action. labelled area of the screen across your body. Split into two teams and nominate until it fills up. players for head-to-head battles while the game tracks your victories. Take on computer GAME MENUS opponents if you’re playing alone. To bring up the Pause menu, hold your left arm out diagonally at around 45° from your body until the Kinect Warranty For Your Copy of Xbox Game Software (“Game”) Acquired in Australia or Guide icon appears. Be sure to face the sensor straight New Zealand on with your legs together and your right arm at your IF YOU ACQUIRED YOUR GAME IN AUSTRALIA OR NEW ZEALAND, THE FOLLOWING side. From this menu you can quit, restart, or access WARRANTY APPLIES TO YOU IN ADDITION the Kinect Tuner if you experience any problems with TO ANY STATUTORY WARRANTIES: Consumer Rights the sensor (or press on an Xbox 360 controller if You may have the benefi t of certain rights or remedies against Microsoft Corpor necessary). -

Kinect Avatars in Real Time

MANUSCRIPT ACCEPTED BY IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON CYBERNETICS, SUBMITTED OCTOBER 16, 2012 1 Create Avatars using Kinect in Real-time Angelos Barmpoutis, Member, IEEE Abstract Real-time 3D reconstruction of the human body has many applications in anthropometry, telecommunications, gaming, fashion, and other areas of human-computer interaction. In this paper a novel framework is presented for reconstructing the 3D model of the human body from a sequence of RGB-D frames. The reconstruction is performed in real time while the human subject moves arbitrarily in front of the camera. The method employs a novel parameterization of cylindrical-type objects using Cartesian tensor and b-spline bases along the radial and longitudinal dimension respectively. The proposed model, dubbed tensor body, is fitted to the input data using a multi-step framework that involves segmentation of the different body regions, robust filtering of the data via a dynamic histogram, and energy-based optimization with positive-definite constraints. A Riemannian metric on the space of positive-definite tensor splines is analytically defined and employed in this framework. The efficacy of the presented methods is demonstrated in several real-data experiments using the Microsoft Kinect sensor. - The full article can be found at the end of this PDF document. The citation of the published article is: A. Barmpoutis. Tensor Body: Real-time Reconstruction of the Human Body and Avatar Synthesis from RGB-D, IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 43(5), Special issue on Computer Vision for RGB-D Sensors: Kinect and Its Applications, October 2013, pp. 1347-1356. Index Terms 3D reconstruction, Avatar, Kinect, Tensor Basis, Positive-Definite constraints, B-Spline. -

Actuaries from Mars!

ACTUARIES FROM MARS! A chartreuse aurora danced on Averie’s ceiling. She knew the glow was from the radiated lake outside her bedroom, but each night as she fell asleep, she preferred to imagine this effervescent ballet was a portal to another dimension. Somewhere, in the beyond, fairies danced among flowers. Elves sang songs that sounded like babbling brooks and felt like summer winds. She longed for a guardian spirit who could whisk her away from the charred trees, unforgiving heat, and gray ash that rendered the world colorless. One of these night, a sprite might escort her from wasteland to Neverland. None ever came - until tonight. The figure appeared suddenly and silently in the corner of her room. He was thin and pale and awkward. He wore khaki pants and a checkered shirt that had more wrinkles than a bag of raisins. Averie rubbed her eyes and slowly sat up to address the imposter. “Who are you?” She crossed her fingers hoping he’d reveal himself to be Oberon, Peter Pan, or maybe Gandalf the Gray. “Bob.” The man said, seeming to prefer the expressionless threads of the carpet to Averie’s inquisitive gaze. “Are you sure?” He shrugged. Averie felt flicker of hope. Maybe he had forgotten his true identity. Amnesia was a common consequence of soured dalliances with spiteful deities. “How did you get here Bob?” “GUBER.” “What?” “Galactic Uber. Well, that’s what we call it anyway. It has a more technical name that I never pronounce correctly. They only drop off at Earth though. So I’m kind of stuck without a ride back.” “Back where?” “Mars.” Averie shivered with excitement. -

Avatar Kinect: Drama in the Virtual Classroom Among L2 Learners of English

The Qualitative Report Volume 24 Number 13 Article 6 4-17-2019 Avatar Kinect: Drama in the Virtual Classroom among L2 Learners of English Robert Bianchi Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, [email protected] Byrad Yyelland Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, [email protected] Joseph John Yang College of the North Atlantic, [email protected] Molly McHarg Independent Researcher, Bangkok, Thailand, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Social Statistics Commons Recommended APA Citation Bianchi, R., Yyelland, B., Yang, J. J., & McHarg, M. (2019). Avatar Kinect: Drama in the Virtual Classroom among L2 Learners of English. The Qualitative Report, 24(13), 58-74. https://doi.org/10.46743/ 2160-3715/2019.4125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Avatar Kinect: Drama in the Virtual Classroom among L2 Learners of English Abstract This study presents a qualitative approach to exploring classroom behaviour using dramaturgical analysis of student interactions in relation with, and as mediated through, a gesture-based gaming software among L2 learners of English at two international branch campuses in the Arabian Gulf where face-to- face interactions between unrelated members of the opposite sex are generally discouraged. We investigated whether Avatar Kinect might provide a safe way for young males and females to interact while discussing social issues in a composition course. -

Enter the Avatar. the Phenomenology of Prosthetic Telepresence in Computer Games

Enter the Avatar. The phenomenology of prosthetic telepresence in computer games. Rune Klevjer Department of Information Science and Media Studies University of Bergen This is a self-archived postprint version of "Enter the Avatar. The phenomenology of prosthetic telepresence in computer games." In The Philosophy of Computer Games, edited by Hallvard Fossheim, Tarjei Mandt Larsen and John Richard Sageng, 17-38. London & New York: Springer. The final publication is available at SpringerLink: http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-007-4249-9/page/1 Abstract In this paper I will give a phenomenological account of embodied presence through computer game avatars, based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s analysis of bodily intentionality, bodily space and bodily extensions (2002 [1962]. The core idea is that when we play, directly controllable avatars like Mario or Lara Croft, as well as racing cars or other kinds of controllable vehicles, function as prosthetic extensions of our own body, which extend into screen space the dual nature of the body as both subject and object. Because they act as proxies or stand-ins for our own body within the gameworld, prosthetic avatars are crucially different from more familiar kinds of bodily extensions, like tools or musical instruments. In navigable 3D environments, the main “body” of the avatar, in the phenomenological sense, is not the controllable marionette itself (for example Mario or Lara), but the navigable virtual camera , which becomes an extension of the player’s locomotive vision during play. In this way, the navigable camera, extending from the player’s eyes and fingers, re-locates the player’s bodily 1 self-awareness – the immediate sense of “here” as opposed to “there” – into screen space. -

The Performative Interactivity of Video Games

SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?: THE PERFORMATIVE INTERACTIVITY OF VIDEO GAMES Michael J. Beck Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: John M. Allison, Jr., Major Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication Studies Justin T. Trudeau, Committee Member Shaun Treat, Committee Member Holley Vaughn, Committee Member Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Beck, Michael J. Shall We Play a Game? The Performative Interactivity of Video Games. Master of Science (Communication Studies), August 2014, 113 pp., bibliography, 61 titles. This study examines the ways that videogames and live performance are informed by play theory. Utilizing performance studies methodologies, specifically personal narrative and autoperformance, the project explores the embodied ways that gamers know and understand videogames. A staged performance, “Shall We Play a Game?,” was crafted using Brechtian theatre techniques and Conquergood’s three A’s of performance, and served as the basis for the examination. This project seeks to dispel popular misconceptions about videogames and performance and to expand understanding about videogaming as an embodied performative practice and a way of knowing that has practical implications for everyday life. Copyright 2014 by Michael J. Beck ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapters 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................. -

The Illusion of Control in Grim Fandango and Virtual Spaces

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Summer 8-10-2017 “On soulless feet we cross the floor...” The Illusion of Control in Grim Fandango and Virtual Spaces Christina Cicchetti CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/219 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “On soulless feet we cross the floor...” The Illusion of Control in Grim Fandango and Virtual Spaces By Christina Cicchetti Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Literature, Language, and Theory Hunter College, The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: 8/14/17 Jeff Allred _______________ ___________________________________ Date Signature Professor Jeff Allred 8/14/17 Amy Robbins _______________ ___________________________________ Date Signature of Second Reader Professor Amy Robbins Compared to the messy, organic landscape of the material world, games provide their players with reliable satisfaction through their clear goals, black-and-white rules, and informative feedback. Cognitive scientist Marvin Minsky argues that “Our connection to the real world is very thin, and our connection with the artificial world is going to be more intimate and satisfying than anything that’s come before” (Minsky). Minsky suggests that the deliberate construction of games satisfies a longing for control that is not satiated by the material world. Gaming, like literature, uses the mechanics of its medium to tell stories. -

Bodyavatar: Creating Freeform 3D Avatars Using First-Person Body

Applications and Games UIST’13, October 8–11, 2013, St. Andrews, UK BodyAvatar: Creating Freeform 3D Avatars using First-Person Body Gestures Yupeng Zhang1,2, Teng Han1,3, Zhimin Ren1,4, Nobuyuki Umetani1,5, Xin Tong1, Yang Liu1, Takaaki Shiratori1, Xiang Cao1,6 1Microsoft Research Asia, 2University of Science and Technology of China, 3University of Bristol, 4University of North Carolina, 5The University of Tokyo, 6Lenovo Research & Technology [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; {xtong, yangliu, takaakis}@microsoft.com; [email protected] (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) Figure 1. Creating a 3D butterfly using BodyAvatar. (a)(a) ScanScan thethe initialinitial shape.shape. (b)(b) DragDrag antennas.antennas. (c)(c) SweepSweep wings.wings. (d)(d) SculptSculpt aa bigbig belly.belly. (e)(e) GrowGrow legs.legs. (f(f) Paint color. ABSTRACT thesethese avatarsavatars cancan nownow directlydirectly mimicmimic players’players’ bodybody BodyAvatar is a Kinect-based interactive system that movement, making the experience ever more immersive. allows users without professional skills to create freeform These 3D avatars are usually designed by professional 3D avatars using body gestures. Unlike existing gesture- game artists, with only limited player customization based 3D modeling tools, BodyAvatar centers around a available such as by selecting from a collection of first-person “you’re the avatar” metaphor, where the user predesigned body parts, colors, and accessories. However, treats their own body as a physical proxy of the virtual if one likes to be more creative and build an imaginary 3D avatar. Based on an intuitive body-centric mapping, the user character of non-predefined forms as their avatar, they performs gestures to their own body as if wanting to modify usually have to master complex 3D modeling software, it, which in turn results in corresponding modifications to much beyond the skills of typical game players.