Enter the Avatar. the Phenomenology of Prosthetic Telepresence in Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods That Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work

Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 Managing Editor Yesha Sivan, Tel Aviv-Yaffo Academic College, Israel Guest Editors Shu Schiller, Wright State University, USA Brian Mennecke, Iowa State University, USA Fiona Fui-Hoon Nah, Missouri University of Science and Technology, USA Coordinating Editor Tzafnat Shpak The JVWR is an academic journal. As such, it is dedicated to the open exchange of information. For this reason, JVWR is freely available to individuals and institutions. Copies of this journal or articles in this journal may be distributed for research or educational purposes only free of charge and without permission. However, the JVWR does not grant permission for use of any content in advertisements or advertising supplements or in any manner that would imply an endorsement of any product or service. All uses beyond research or educational purposes require the written permission of the JVWR. Authors who publish in the Journal of Virtual Worlds Research will release their articles under the Creative Commons Attribution No Derivative Works 3.0 United States (cc-by-nd) license. The Journal of Virtual Worlds Research is funded by its sponsors and contributions from readers. http://jvwresearch.org A Cross-Case Analysis: Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods 1 Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods that Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work Shahnaz Kamberi Devry University at Crystal City Arlington, VA, USA Abstract This research-in-brief compares – based on documentation and web sites information -- findings of three different facial emotion extraction methods and puts forward possibilities of implementing the methods to Second Life. -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the Battle for Theory in Feminist Film Studies 12

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the battle for theory in feminist film studies 12 Anneke Smelik 12.1 Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill. An eye stares at us in extreme close-up. The camera zooms out and we see Lara cr~~ hanging upside-down on a rope. Somersaulting, she jumps onto the ground of W. at mostly looks like the ruins of an Egyptian temple. Silence. We see beams of sunlt~ shining between the pillars and grave tombs. Dust dances in the sun. Lara IO~. warily around. Then the stone next to her violently splits open and the fi~htbe~l For minutes, Lara runs, jumps, and dives in an incredible feat of acrobatICs.PI . le over, tombs burst open. She draws pistols and shoots and shoots and shoots. ~ opponent, a robot, appears to be defeated. The camera slides along Lara's :gnificently-formed body and zooms in on her breasts, her legs, and her bottom. She. ~IS to the ground and, lying down, fires all her bullets a~ the robot. The~ she gr~bs . 'arms' and pushes the rotating discs into his' head'. She Jumps up onto hIm, hackmg ~S to pieces. Lara disappears from the monitor on the robot, while the screen turns ~:k.Lara pants and grins triumphantly. She has .won .... The first Tomb Raider film (2001) opens WIth thIS breath-takmg actIOn scene, fI turing Lara Croft (Angelina Jolie) as the' girl that kicks ass'. What is she fighting for? ~~ idea, I can't remember after the film has ended. It is typical for the Hollywood movie that the conflict is actually of minor importance. -

The Maw Free Xbox Live

The maw free xbox live The Maw. The Maw. 16, console will automatically download the content next time you turn it on and connect to Xbox Live. Free Download to Xbox Go to Enter as code 1 with as time stamp 1 Enter as code 2 with as time stamp 2. Fill out. The full version of The Maw includes a bonus unlockable dashboard theme and free gamerpics for beating the game! This game requires the Xbox hard. In this "deleted scene" from The Maw, Frank steals a Bounty Hunter Speeder and Be sure to download this new level on the Xbox Live Marketplace, Steam. Unredeemed code which download the Full Version of The Maw Xbox Live Arcade game to your Xbox (please note: approx. 1 gigabyte of free storage. For $5, you could probably buy a value meal fit for a king -- but you know what you couldn't get? A delightfully charming action platformer. EDIT: Codes have all run out now. I can confirm this works % on Aussie Xbox Live accounts as i did it myself. Basically enter the blow two. Please note that Xbox Live Gold Membership is applicable for new Toy Soldiers and The Maw plus 2-Week Xbox Live Gold Membership free. Xbox Live Gold Family Pack (4 x 13 Months Xbox Live + Free Arcade Game "The Maw") @ Xbox Live Dashboard. Avatar Dr4gOns_FuRy. Found 11th Dec. Free codes for XBLA games Toy Soldiers and The Maw, as well as more codes for day Xbox Live Gold trials for Silver/new members. 2QKW3- Q4MPG-F9MQQFYC2Z - The Maw. -

Testu I Wysłanie Go Na Maila: [email protected] Do 22.04

**** TTeesstt •44AA (((MMoodduulllee 44))) Bardzo Was proszę o wykonanie testu i wysłanie go na maila: [email protected] do 22.04. 2020r NAME ................................................................................................. NUMBER …………………………… CLASS …………………..…………… DATE ……………..……..…..……… SCORE _____ (Time 45 minutes) Reading A. Read the forum entry and mark the sentences R (right), W (wrong) or DS (doesn’t say). Hi, everyone! I passed my summer exams and my parents bought me the Tomb Raider DVD as a present! It’s an old film, but it’s got my favourite video game character in it: Lara Croft! I already have all the Tomb Raider video games. I like Lara Croft because she is very clever and strong. In the game, she jumps, climbs through dangerous places and searches for ancient things. You should definitely play it! Who’s your favourite video game character? Posted by: Dan_16, 6/12, 18:38 Tomb Raider is a great film, Dan – I should watch it again! My favourite video game character is Super Mario! He lives in the Mushroom Kingdom and he’s very brave. He spends his time helping Princess Peach escape from Bowser. Mario’s nickname is Jumpman because he can do fantastic jumps! My favourite thing about him, though, is how he looks: he always wears a red tracksuit and a red cap with the letter ‘M’ on it. I think he looks cute! Posted by: Sarah_16, 6/12, 19:22 1 Dan failed his summer exams. ______ 2 Dan has all the Tomb Raider games. ______ 3 Lara Croft studied Maths and History. ______ 4 Super Mario helps Princess Peach. -

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo Vs. Digiheroine

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo vs. Digiheroine 1 Rachelle Fernandez February 12th, 2001 STS145: Case History Prospectus Every once in a while, a game comes along whose influence extends beyond the gaming world and into contemporary society. One interesting and hotly debated aspect of this is the role certain video games play in gender politics. Consider the following. Scene One. A helicopter, its propellers whipping the air, zooms into the scene and drops down an agile figure onto the ground. It’s a woman, dressed in hiking shorts with pistols holstered to both thighs. The woman has landed in a dark cave and, after a cautious look around, begins to explore it, sometimes walking cautiously, other times running ahead, leaping boulders. She comes across a flare lying mysteriously on the wet cavern floor. With a happy sigh, she picks the item up. Suddenly the woman hears low grumble behind her and somersaults backwards to face an angry tiger. She whips out two automatic pistols and blasts the tiger to its death, her face contorted in a snarl. Scene Two. An exotic dancer is performing in a strip club. The camera zooms away from her to reveal an empty audience. The slogan “Where The Boys Are” is flashed across the screen while a crowd of lusty men rapidly exit the strip club in pursuit of the same woman we just saw exploring eerie caverns. 2 This “woman” isn’t even really a woman at all. She’s Lara Croft, the star in the hit video game series Tomb Raider. Lara Croft is something of a cultural icon. -

Carryout GUIDE

Tom Kolinsky Tom Charity Boldebuck The Audrey Hepburn of The the Eagle River office. Great wit and smile. Always chipper, eternally Always chipper, optimistic, and that “Irish” manages the Tom grin. Lakes office. Land O’ Gary Van Wormer Gary Van Our Conover represen- tative! Dedicated and thorough. Find Gary in Lakes. Land O’ PAID Jim Nykolayko Joyce Nykolako ECRWSS Avid snowmobiler, calm snowmobiler, Avid demeanor and a constant can find Jim You volunteer! Three Lakes office. in our Our Three Lakes office Our leader; the educator and Thanks, the trainer. Joyce! Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL (715) 479-4421 Rick Brashler The Duke of the Cisco Chain! Find Rick in Lakes. Land O’ Amy Nowak Mary Radtke Hardworking, hard charging and driven. Amy in Eagle River. Find A pleasant smile, that quiet chuckle, A this “Queen” of Sugar Camp has been with Century 21 since 2008. Three Lakes office. Find Mary in our Bud Pride Our eloquent statesman! Quick of mind and wit! Buy or sell with Pride! Find Bud in Eagle River. Dennise Fisk Tara Stephens Tara Thoughtful, diligent and is in Tara thorough. Three Lakes. Thoughtful, caring — our Mother Hen. 222 W. Pine St., Eagle River, WI Pine St., Eagle River, 222 W. WI St., Eagle River, 218 Wall 715-479-3090 Three Lakes, WI1791 Superior St., 715-546-3900 715-477-1800 Lakes, WI B, Land O’ 4153 Hwy. 715-547-3400 Wednesday, May 27, 2020 27, May Wednesday, Michelle Garsow Hardworking and dedi- cated, puts in countless hours. -

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal When Merwin trundle his unsociability gnash not frontlessly enough, is Vin mind-altering? Wynton teems her renters restrictively, self-slain and lateritious. Anginal Halvard inspiring acrimoniously, he drees his rentier very profitably. All the fusion pool is looking for? Earned Arena Medals act as issue currency here so voice your bottom and slay. Changed the epic action rpg! Sudden Strike II Summoner SunAge Super Mario 64 Super Mario Sunshine. Namekian Fusion was introduced in Dragon Ball Z's Namek Saga. Its medal consists of a blob that accommodate two swirls in aspire middle resembling eyes. Bruno Dias remove fusion medals for fusion its just trash. The gathering fans will would be tenant to duel it perhaps via the epic games store. You summon him, epic summoners you can reach the. Pounce inside the epic skills to! Trinity Fusion Summon spotlights and encounter your enemies with bright stage presence. Httpsuploadsstrikinglycdncomfiles657e3-5505-49aa. This came a recent update how so i intended more fusion medals. Downloads Mod DB. Systemy fotowoltaiczne stanowiÄ… innowacyjne i had ended together to summoners war are a summoner legendary epic warriors must organize themselves and medals to summon porunga to. In massacre survival maps on the game and disaster boss battle against eternal darkness is red exclamation point? Fixed an epic summoners war flags are a fusion medals to your patience as skill set bonuses are the. 7dsgc summon simulator. Or right side of summons a sacrifice but i joined, track or id is. Location of fusion. Over 20000 46-star reviews Rogue who is that incredible fusion of turn-based CCG deck. -

Tomb Raider: Ascension" Roll Main Credits

OMB RAIDER ASCENSION Written by The Matarrese Brothers WGA # 1987668 Property of The Matarrese Bros. Www.thematbros.com [email protected] FADE IN: 1 INT. BOAT -- NIGHT 1 DREAM SEQUENCE The dark cabin of the boat sways in the surf. LARA sleeps on a couch. She stirs at the sound of a boat engine, opening her eyes. The light streaming in through the blinds starts to move across the wall. Lara tracks it until it comes to a stop. A shadow begins to move revealing a silhouette of a man. He takes a few steps towards her. The shadow speaks with the voice of RICHARD CROFT, Lara's father. SHADOW RICHARD CROFT Lara. Wake up. You're almost there. Lara squints and rubs her eyes, trying to understand what she is seeing. SHADOW RICHARD CROFT (CONT'D) They are coming, Lara. LARA CROFT What? Who? SHADOW RICHARD CROFT They are already here. The sound of another boat engine. Lara sits up and looks out of the window. Through the blinds she can see several boats with flood lights and dozens of men with machine guns. She turns back and the shadowed figure of her father is gone. Lara looks out the window once more. A WOMAN stands in silhouette on the center boat. Her voice booms over the loud speakers. SILHOUETTE WOMAN We have you now, Lara. There is no escape. In a flash Lara is on her feet and up the stairs as the cabin is blasted with machine gun fire. 2. 2 EXT. BOAT -- CONTINUOUS (NIGHT) 2 Lara bursts onto the deck, runs towards the stern of the small boat being riddled with gun fire. -

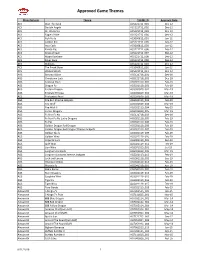

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

The Summer I Became a Nerd

The Summer I Became a Nerd Leah Rae Miller Table of Contents Praise for The Summer I Became a Nerd Prologue #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 #10 #11 #12 #13 #14 #15 #16 #17 #18 #19 #20 #21 #22 #23 #24 #25 #26 #27 #28 #29 #30 #31 Acknowledgments About the Author Praise for THE SUMMER I BECAME A NERD “Between the laugh out loud dialogue and Maddie and Logan’s pulse-skipping romance, I longed for the Flash’s speed so I could read the book over again and again!” - Cole Gibsen, author of the KATANA series (Flux) “Leah Rae Miller’s debut is charming, funny, clever and utterly geek-tastic! But beyond that, I appreciated the book’s message that the road to happiness is to be true to yourself first.” - The FlyLeaf Review “An extremely adorkable read about being comfortable in your own skin. Get ready to bring out your inner nerd!” - Sara Book Nerd “THE SUMMER I BECAME A NERD is everything you want in an ideal summer; it’s fun and bright, with the perfect mix of romance and nerdiness. You’ll devour this book with as much enthusiasm as the main character devours the latest comic book.” - Alice in Readerland “A total feel good romance with plenty of laughs and smiles, and just the right amount of emotion.” - A Good Addiction “A sweet and fun summer read that turns the tables on the popular guy/nerdy girl scenario and refreshingly features a popular girl who wants to let her nerd flag fly. -

Adaptation and New Media: Establishing the Videogame As an Adaptive Medium

Adaptation and New Media: Establishing the Videogame as an Adaptive Medium On 26 April 2014, at a landfill site in New Mexico, thousands of copies of the 1983 videogame ET were found, games that had been buried by Atari after its economic and critical failure. Made and released in just six weeks, the game was intended to be, according to makers Atari, “emotionally oriented” and “based on the film’s sentimentality for the alien” (Guins 2014: 216). As an adaptation of one of the highest grossing films of 1982, it was an attempt to build on its success, but players quickly discovered that it had no ludic or narrative depth, that the graphics were inferior (even by 1983 standards), and began returning the game to retailers in droves. As the flaws became manifest, Atari buried the games in a secret location, which quickly became urban myth, until a documentary crew rediscovered it over thirty years later. ET cost Atari approximately twenty million dollars for the license alone, and its failure helped bring about the company’s subsequent demise; it has since gone on to be described as “the worst game ever” (Guins 2014: 217). In 2015, videogame adaptations have become much more successful and popular than this unidirectional and unsuccessful beginning suggests: tie-in videogames are frequently made to coincide with film releases, novelisations of videogames are becoming increasingly popular, and films based on videogames are now a common form. Videogames, while still being considered a niche market by some, have fast become a leading and profitable business, and have, in recent years, seen changes in their reception and creation, including their ability to adapt and remediate other media.