Adaptation and New Media: Establishing the Videogame As an Adaptive Medium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Januar Februar

brezpla~ni izvod po{tnina pla~ana pri po{ti 1106 ljubljana kinote~nik 2011 2012 januar-februar Rainer Werner Fassbinder retrospektiva ostanite {e naprej z nami Televizijskim ogledom in uvidom sledi {e ob{irnej{a, po skoraj dvajsetletnem "Televizija! Vzgojiteljica, mati, ljubica." doma~em zamolku toliko glasnej{a retrospektiva nem{kega scenarista, dramatika, Homer Simpson igralca, producenta in re`iserja Rainerja Wernerja Fassbinderja, ki bo prinesla "Za film bi rad pomenil to, kar Shakespeare pomeni za gledali{~e, Marx za {tirideset projekcij dvajsetih filmov plus – kot je pri ve~jih retrospektivah spet v politiko in Freud za psihologijo: nekdo, za komer ni~ ne ostane isto." navadi – zajeten kinote~ni katalog, posve~en avtorju. Kdor je Fassbinderja `e Rainer Werner Fassbinder gledal, ga bo pri{el pogledat spet (retrospektiva, mimogrede, prina{a kup , letnik XII, {tevilka 5–6, januar-februar 2012 naslovov, ki v Sloveniji {e nikoli niso bili predvajani na velikem platnu). Kdor Kaj imata skupnega televizija in Rainer Werner Fassbinder razen tega, da je prva Fassbinderja {e ni gledal, pa ima v Kinoteki rezerviran abonma ne samo pri radikalno posegla v tok navad in obna{anja 20. stoletja, drugi pa ni~ manj predmetu filma, pa~ pa tudi na podro~ju ob~utljivih to~k evropske zgodovine radikalno v tok filmske zgodovine istega stoletja? Poleg dejstva, da je Fassbinder dvajsetega stoletja, brezkompromisnega politi~nega udejstvovanja, eti~nega pribli`no tretjino svojega enormnega opusa posnel prav za televizijo, ju tokrat anga`maja in njemu pripadajo~ega dogodka ljubezni. dru`i tudi skupen nastop v januarsko-februarskem programu Kinoteke. Retrospektiva se bo iz januarja prelila v februar, ta pa se sklepa z mnogo manj ali Tega na samem pragu novega leta odpiramo z ob{irno, tematsko retrospektivo, prav ni~ "kanoni~no", a zato ni~ manj "pou~no" retrospektivo, ki bo predstavila ki smo jo poimenovali Ekrani na platnu in v sklopu katere raziskujemo, na kak{ne pet filmov Reze Mirkarimija, mlaj{ega cineasta iranskega rodu. -

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography 1 The

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Films and Television Series mentioned or discussed during the master class Game of Thrones (2011-2013). 2 seasons, 20 episodes. Creators: David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, U.S.A. Airs on HBO. Production Co.: HBO / Television 360 / Grok! Studio / Generator Entertainment / Bighead Littlehead / Embassy Films. The Twilight Zone (1959-1964). 5 seasons, 156 episodes. Creator: Rod Sterling, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS. Production Co.: Cayuga Productions / CBS. Captain Video and His Video Rangers (1949-1955). 7 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: James Caddiga, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: DuMont Television Network. Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954). 2 seasons, 39 episodes. Creator: Roland D. Reed, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: Roland Reed Productions / Space Ranger Enterprises. Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (1950-1955). 4 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: unknown, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS (1950), ABC (1951-1952), DuMont Television Network (1953-1954), and NBC (1954-1955). -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

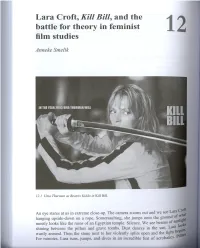

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the Battle for Theory in Feminist Film Studies 12

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the battle for theory in feminist film studies 12 Anneke Smelik 12.1 Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill. An eye stares at us in extreme close-up. The camera zooms out and we see Lara cr~~ hanging upside-down on a rope. Somersaulting, she jumps onto the ground of W. at mostly looks like the ruins of an Egyptian temple. Silence. We see beams of sunlt~ shining between the pillars and grave tombs. Dust dances in the sun. Lara IO~. warily around. Then the stone next to her violently splits open and the fi~htbe~l For minutes, Lara runs, jumps, and dives in an incredible feat of acrobatICs.PI . le over, tombs burst open. She draws pistols and shoots and shoots and shoots. ~ opponent, a robot, appears to be defeated. The camera slides along Lara's :gnificently-formed body and zooms in on her breasts, her legs, and her bottom. She. ~IS to the ground and, lying down, fires all her bullets a~ the robot. The~ she gr~bs . 'arms' and pushes the rotating discs into his' head'. She Jumps up onto hIm, hackmg ~S to pieces. Lara disappears from the monitor on the robot, while the screen turns ~:k.Lara pants and grins triumphantly. She has .won .... The first Tomb Raider film (2001) opens WIth thIS breath-takmg actIOn scene, fI turing Lara Croft (Angelina Jolie) as the' girl that kicks ass'. What is she fighting for? ~~ idea, I can't remember after the film has ended. It is typical for the Hollywood movie that the conflict is actually of minor importance. -

Navigating the Videogame

From above, from below: navigating the videogame A thesis presented by Daniel Golding 228306 to The School of Culture and Communication in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the field of Cultural Studies in the School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Supervisor: Dr. Fran Martin October 2008 ABSTRACT The study of videogames is still evolving. While many theorists have accurately described aspects of the medium, this thesis seeks to move the study of videogames away from previously formal approaches and towards a holistic method of engagement with the experience of playing videogames. Therefore, I propose that videogames are best conceptualised as navigable, spatial texts. This approach, based on Michel de Certeau’s concept of strategies and tactics, illuminates both the textual structure of videogames and the immediate experience of playing them. I also regard videogame space as paramount. My close analysis of Portal (Valve Corporation, 2007) demonstrates that a designer can choose to communicate rules and fiction, and attempt to influence the behaviour of players through strategies of space. Therefore, I aim to plot the relationship between designer and player through the power structures of the videogame, as conceived through this new lens. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 AN EVOLVING FIELD 2 LUDOLOGY AND NARRATOLOGY 3 DEFINITIONS, AND THE NAVIGABLE TEXT 6 PLAYER EXPERIENCE AND VIDEOGAME SPACE 11 MARGINS OF DISCUSSION 13 CHAPTER TWO: The videogame from above: the designer as strategist 18 PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY 18 PORTAL AND THE STRATEGIES OF DESIGN 20 STRUCTURES OF POWER 27 RAILS 29 CHAPTER THREE: The videogame from below: the player as tactician 34 THE PLAYER AS NAVIGATOR 36 THE PLAYER AS SUBJECT 38 THE PLAYER AS BRICOLEUR 40 THE PLAYER AS GUERRILLA 43 CHAPTER FOUR: Conclusion 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY 50 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. -

Testu I Wysłanie Go Na Maila: [email protected] Do 22.04

**** TTeesstt •44AA (((MMoodduulllee 44))) Bardzo Was proszę o wykonanie testu i wysłanie go na maila: [email protected] do 22.04. 2020r NAME ................................................................................................. NUMBER …………………………… CLASS …………………..…………… DATE ……………..……..…..……… SCORE _____ (Time 45 minutes) Reading A. Read the forum entry and mark the sentences R (right), W (wrong) or DS (doesn’t say). Hi, everyone! I passed my summer exams and my parents bought me the Tomb Raider DVD as a present! It’s an old film, but it’s got my favourite video game character in it: Lara Croft! I already have all the Tomb Raider video games. I like Lara Croft because she is very clever and strong. In the game, she jumps, climbs through dangerous places and searches for ancient things. You should definitely play it! Who’s your favourite video game character? Posted by: Dan_16, 6/12, 18:38 Tomb Raider is a great film, Dan – I should watch it again! My favourite video game character is Super Mario! He lives in the Mushroom Kingdom and he’s very brave. He spends his time helping Princess Peach escape from Bowser. Mario’s nickname is Jumpman because he can do fantastic jumps! My favourite thing about him, though, is how he looks: he always wears a red tracksuit and a red cap with the letter ‘M’ on it. I think he looks cute! Posted by: Sarah_16, 6/12, 19:22 1 Dan failed his summer exams. ______ 2 Dan has all the Tomb Raider games. ______ 3 Lara Croft studied Maths and History. ______ 4 Super Mario helps Princess Peach. -

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo Vs. Digiheroine

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo vs. Digiheroine 1 Rachelle Fernandez February 12th, 2001 STS145: Case History Prospectus Every once in a while, a game comes along whose influence extends beyond the gaming world and into contemporary society. One interesting and hotly debated aspect of this is the role certain video games play in gender politics. Consider the following. Scene One. A helicopter, its propellers whipping the air, zooms into the scene and drops down an agile figure onto the ground. It’s a woman, dressed in hiking shorts with pistols holstered to both thighs. The woman has landed in a dark cave and, after a cautious look around, begins to explore it, sometimes walking cautiously, other times running ahead, leaping boulders. She comes across a flare lying mysteriously on the wet cavern floor. With a happy sigh, she picks the item up. Suddenly the woman hears low grumble behind her and somersaults backwards to face an angry tiger. She whips out two automatic pistols and blasts the tiger to its death, her face contorted in a snarl. Scene Two. An exotic dancer is performing in a strip club. The camera zooms away from her to reveal an empty audience. The slogan “Where The Boys Are” is flashed across the screen while a crowd of lusty men rapidly exit the strip club in pursuit of the same woman we just saw exploring eerie caverns. 2 This “woman” isn’t even really a woman at all. She’s Lara Croft, the star in the hit video game series Tomb Raider. Lara Croft is something of a cultural icon. -

Uk Films for Sale in Cannes 2009

UK FILMS FOR SALE IN CANNES 2009 Supported by Produced by 1234 TMoviehouse Entertainment Cast: Ian Bonar, Lyndsey Marshal, Kieran Bew, Mathew Baynton Gary Phillips Genre: Drama Rés. Du Grand Hotel 47 La Croisette, 6Th Director: Giles Borg Floor Producer Simon Kearney Tel: +33 4 93 38 65 93 Status : Completed [email protected] Home Office Tel: +44 20 7836 5536 Synopsis Ardent musician Stevie (guitar, vocals) endures a day-job he despises and can't find a girlfriend but... at least he has his music! With friend Neil (drums) he's been kicking around for a while not achieving much but when the pair of misfits team-up with the more-experienced Billy (guitar) and his cute pal Emily (bass) the possibility they might be on to something really good presents itself. For Stevie this is the opportunity he's been waiting for with the band and just maybe... Emily too! 13 Hrs TEyeline Entertainment Cast: Isabella Calthorpe, Gemma Atkinson, Tom Felton, Joshua Duncan Napier-Bell Bowman Lerins Stand R10 Genre: Horror Tel: +33 4 92 99 33 02 Director: Jonathan Glendening [email protected] Writer: Adam Phillips Home Office Tel: +44 20 8144 2994 Producer Nick Napier-Bell, Romain Schroeder, Tom Reeve Status : Post-Production Synopsis A full moon hangs in the night sky and lightning streaks across dark storm clouds. Sarah Tyler returns to her troubled family home in the isolated countryside, for a much put-off visit. As the storm rages on, Sarah, her family and friends shore up for the night, cut off from the outside world. -

Carryout GUIDE

Tom Kolinsky Tom Charity Boldebuck The Audrey Hepburn of The the Eagle River office. Great wit and smile. Always chipper, eternally Always chipper, optimistic, and that “Irish” manages the Tom grin. Lakes office. Land O’ Gary Van Wormer Gary Van Our Conover represen- tative! Dedicated and thorough. Find Gary in Lakes. Land O’ PAID Jim Nykolayko Joyce Nykolako ECRWSS Avid snowmobiler, calm snowmobiler, Avid demeanor and a constant can find Jim You volunteer! Three Lakes office. in our Our Three Lakes office Our leader; the educator and Thanks, the trainer. Joyce! Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL (715) 479-4421 Rick Brashler The Duke of the Cisco Chain! Find Rick in Lakes. Land O’ Amy Nowak Mary Radtke Hardworking, hard charging and driven. Amy in Eagle River. Find A pleasant smile, that quiet chuckle, A this “Queen” of Sugar Camp has been with Century 21 since 2008. Three Lakes office. Find Mary in our Bud Pride Our eloquent statesman! Quick of mind and wit! Buy or sell with Pride! Find Bud in Eagle River. Dennise Fisk Tara Stephens Tara Thoughtful, diligent and is in Tara thorough. Three Lakes. Thoughtful, caring — our Mother Hen. 222 W. Pine St., Eagle River, WI Pine St., Eagle River, 222 W. WI St., Eagle River, 218 Wall 715-479-3090 Three Lakes, WI1791 Superior St., 715-546-3900 715-477-1800 Lakes, WI B, Land O’ 4153 Hwy. 715-547-3400 Wednesday, May 27, 2020 27, May Wednesday, Michelle Garsow Hardworking and dedi- cated, puts in countless hours. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Jessica L. Aldred Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Tomb Raider: Ascension" Roll Main Credits

OMB RAIDER ASCENSION Written by The Matarrese Brothers WGA # 1987668 Property of The Matarrese Bros. Www.thematbros.com [email protected] FADE IN: 1 INT. BOAT -- NIGHT 1 DREAM SEQUENCE The dark cabin of the boat sways in the surf. LARA sleeps on a couch. She stirs at the sound of a boat engine, opening her eyes. The light streaming in through the blinds starts to move across the wall. Lara tracks it until it comes to a stop. A shadow begins to move revealing a silhouette of a man. He takes a few steps towards her. The shadow speaks with the voice of RICHARD CROFT, Lara's father. SHADOW RICHARD CROFT Lara. Wake up. You're almost there. Lara squints and rubs her eyes, trying to understand what she is seeing. SHADOW RICHARD CROFT (CONT'D) They are coming, Lara. LARA CROFT What? Who? SHADOW RICHARD CROFT They are already here. The sound of another boat engine. Lara sits up and looks out of the window. Through the blinds she can see several boats with flood lights and dozens of men with machine guns. She turns back and the shadowed figure of her father is gone. Lara looks out the window once more. A WOMAN stands in silhouette on the center boat. Her voice booms over the loud speakers. SILHOUETTE WOMAN We have you now, Lara. There is no escape. In a flash Lara is on her feet and up the stairs as the cabin is blasted with machine gun fire. 2. 2 EXT. BOAT -- CONTINUOUS (NIGHT) 2 Lara bursts onto the deck, runs towards the stern of the small boat being riddled with gun fire.