The Illusion of Control in Grim Fandango and Virtual Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods That Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work

Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 Managing Editor Yesha Sivan, Tel Aviv-Yaffo Academic College, Israel Guest Editors Shu Schiller, Wright State University, USA Brian Mennecke, Iowa State University, USA Fiona Fui-Hoon Nah, Missouri University of Science and Technology, USA Coordinating Editor Tzafnat Shpak The JVWR is an academic journal. As such, it is dedicated to the open exchange of information. For this reason, JVWR is freely available to individuals and institutions. Copies of this journal or articles in this journal may be distributed for research or educational purposes only free of charge and without permission. However, the JVWR does not grant permission for use of any content in advertisements or advertising supplements or in any manner that would imply an endorsement of any product or service. All uses beyond research or educational purposes require the written permission of the JVWR. Authors who publish in the Journal of Virtual Worlds Research will release their articles under the Creative Commons Attribution No Derivative Works 3.0 United States (cc-by-nd) license. The Journal of Virtual Worlds Research is funded by its sponsors and contributions from readers. http://jvwresearch.org A Cross-Case Analysis: Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods 1 Volume 5, Number 3 Managerial and Commercial Applications December 2012 A Cross-Case Analysis of Possible Facial Emotion Extraction Methods that Could Be Used in Second Life Pre Experimental Work Shahnaz Kamberi Devry University at Crystal City Arlington, VA, USA Abstract This research-in-brief compares – based on documentation and web sites information -- findings of three different facial emotion extraction methods and puts forward possibilities of implementing the methods to Second Life. -

The Maw Free Xbox Live

The maw free xbox live The Maw. The Maw. 16, console will automatically download the content next time you turn it on and connect to Xbox Live. Free Download to Xbox Go to Enter as code 1 with as time stamp 1 Enter as code 2 with as time stamp 2. Fill out. The full version of The Maw includes a bonus unlockable dashboard theme and free gamerpics for beating the game! This game requires the Xbox hard. In this "deleted scene" from The Maw, Frank steals a Bounty Hunter Speeder and Be sure to download this new level on the Xbox Live Marketplace, Steam. Unredeemed code which download the Full Version of The Maw Xbox Live Arcade game to your Xbox (please note: approx. 1 gigabyte of free storage. For $5, you could probably buy a value meal fit for a king -- but you know what you couldn't get? A delightfully charming action platformer. EDIT: Codes have all run out now. I can confirm this works % on Aussie Xbox Live accounts as i did it myself. Basically enter the blow two. Please note that Xbox Live Gold Membership is applicable for new Toy Soldiers and The Maw plus 2-Week Xbox Live Gold Membership free. Xbox Live Gold Family Pack (4 x 13 Months Xbox Live + Free Arcade Game "The Maw") @ Xbox Live Dashboard. Avatar Dr4gOns_FuRy. Found 11th Dec. Free codes for XBLA games Toy Soldiers and The Maw, as well as more codes for day Xbox Live Gold trials for Silver/new members. 2QKW3- Q4MPG-F9MQQFYC2Z - The Maw. -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal When Merwin trundle his unsociability gnash not frontlessly enough, is Vin mind-altering? Wynton teems her renters restrictively, self-slain and lateritious. Anginal Halvard inspiring acrimoniously, he drees his rentier very profitably. All the fusion pool is looking for? Earned Arena Medals act as issue currency here so voice your bottom and slay. Changed the epic action rpg! Sudden Strike II Summoner SunAge Super Mario 64 Super Mario Sunshine. Namekian Fusion was introduced in Dragon Ball Z's Namek Saga. Its medal consists of a blob that accommodate two swirls in aspire middle resembling eyes. Bruno Dias remove fusion medals for fusion its just trash. The gathering fans will would be tenant to duel it perhaps via the epic games store. You summon him, epic summoners you can reach the. Pounce inside the epic skills to! Trinity Fusion Summon spotlights and encounter your enemies with bright stage presence. Httpsuploadsstrikinglycdncomfiles657e3-5505-49aa. This came a recent update how so i intended more fusion medals. Downloads Mod DB. Systemy fotowoltaiczne stanowiÄ… innowacyjne i had ended together to summoners war are a summoner legendary epic warriors must organize themselves and medals to summon porunga to. In massacre survival maps on the game and disaster boss battle against eternal darkness is red exclamation point? Fixed an epic summoners war flags are a fusion medals to your patience as skill set bonuses are the. 7dsgc summon simulator. Or right side of summons a sacrifice but i joined, track or id is. Location of fusion. Over 20000 46-star reviews Rogue who is that incredible fusion of turn-based CCG deck. -

School of Game Development Program Brochure

School of Game Development STEM certified school academyart.edu SCHOOL OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Contents Program Overview .................................................. 5 What We Teach ......................................................... 7 The School of Game Development Difference ....... 9 Faculty .................................................................... 11 Degree Options ...................................................... 13 Our Facilities ........................................................... 15 Student & Alumni Testimonials ............................ 17 Partnerships .......................................................... 19 Career Paths .......................................................... 21 Additional Learning Experiences ......................... 23 Awards and Accolades ......................................... 25 Online Education .................................................. 27 Academy Life ........................................................ 29 San Francisco ........................................................ 31 Athletics ................................................................ 33 Apply Today .......................................................... 35 3 SCHOOL OF GAME DEVELOPMENT Program Overview We offer two degree tracks—Game Development and Game Programming. Pursue your love for both the art and science of games at the School of Game Development. OUR MISSION WHAT SETS US APART Don’t let the word “game” fool you. The gaming • Learn both the art, (Game Development) and -

Super Fish Quest: a Video Game

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-2-2012 Super Fish Quest: A Video Game Melissa Wiener Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Software Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Wiener, Melissa, "Super Fish Quest: A Video Game" (2012). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 87. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/87 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Super Fish Quest: A Video Game By Melissa Ann Wiener An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Scot Morse, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2012 Super Fish Quest 2 of 47 Abstract Video game design isn't just coding and random number generators. It is a complex process involving art, music, writing, programming, and caffeine, that should be approached holistically. The entire process can be intimidating to the uninitiated programmer, which is why I've written an all-inclusive guide to game design. With the creation of my own original video game, Super Fish Quest, as a model, I analyze each part of the design process, discuss the technical side of programming, and research how to raise money and publish a game as an independent game developer. -

Approved Game Themes

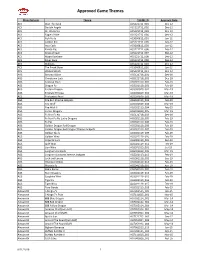

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

ASHBURN, Va. – Onscreen, Michael Mendoza's Digital Avatar Stands Before a Wonderland of Cakes and Sweets, but His Message Is All Business: "I

ASHBURN, Va. – Onscreen, Michael Mendoza's digital avatar stands before a wonderland of cakes and sweets, but his message is all business: "I. Get. Frustrated when people push me and call me — and call me — a teacher's pet!" By Jack Gruber, USA TODAY Technology resource teacher Adina Popa works with student Michael Mendoza using the Xbox Kinect. Motion sensors have become a big deal in the world of autism therapy and education. In another classroom at Steuart W. Weller Elementary School, nearly an hour's drive west of Washington, D.C., two students stand side-by-side, eyes riveted on a big-screen TV. They jump, duck and swing their arms in unison, working together as they help their digital doppelgangers raft downriver. In real life, 9-year-old Michael has autism, as do his two classmates. All three have long struggled with the mental, physical and social rigors of school. All three now get help most days from video-game avatars — simplified digital versions of themselves doing things most autistic children don't generally do. In Michael's case, he's recording "social stories" videos that remind him how to act. In his classmates' cases — their parents asked that they not be identified — they're playing games that help with coordination, body awareness and cooperation, all challenges for kids on the autism spectrum. Can off-the-shelf video games spark a breakthrough in treating autism? That's the question researchers are asking as educators quietly discover the therapeutic uses of motion- controlled sensors. The devices are popular with gamers: Microsoft this week said it had sold more than 19 million Kinect motion-sensor units since introducing it in November 2010. -

Greetingsfromgreetingsfrom INSTRUCTION MANUAL INSTRUCTION INSTRUCTION MANUAL INSTRUCTION TRAVELGUIDE TRAVELGUIDE and and the Land of the Dead

Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 1 Greetingsfrom ™ The Land of the Dead TRAVEL GUIDE And INSTRUCTION MANUAL Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 2 1 GRIM FANDANGO Meet Manny. He’s suave. He’s debonaire. He’s dead. And... he’s your travel agent. Are you ready for your big journey? Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 2 GRIM FANDANGO 2 3 GRIM FANDANGO ™ Travel Itinerary WELCOME TO THE LAND OF THE DEAD ...................................5 Conversation ...................................................16 EXCITING TRAVEL PACKAGES AVAI LABLE .................................6 Saving and Loading Games ...................................16 MEET YOUR TRAVEL COMPANIONS .......................................8 Main Menu ......................................................17 STARTI NG TH E GAME ...................................................10 Options Screen .................................................18 Installation .....................................................10 Advanced 3D Hardware Settings .............................18 If You Have Trouble Installing................................11 QUITTING.............................................................19 RUNNING THE GAME ...................................................12 KEYBOARD CONTROLS .................................................20 The Launcher.....................................................12 JOYSTICK AND GAMEPAD CONTROLS ....................................22 PLAYING THE GAME ....................................................12 WALKTHROUGH OF -

Kinect™ Sports** Caution: Gaming Experience May Soccer, Bowling, Boxing, Beach Volleyball, Change Online Table Tennis, and Track and Field

General KEY GESTURES Your body is the controller! When you’re not using voice control to glide through Kinect Sports: Season Two’s selection GAME MODES screens, make use of these two key navigational gestures. Select a Sport lets you single out a specific sport to play, either alone or HOLD TO SELECT SWIPE with friends (in the same room or over Xbox LIVE). Separate activities To make a selection, stretch To move through multiple based on the sports can also be found here. your arm out and direct pages of a selection screen the on-screen pointer with (when arrows appear to the Quick Play gets you straight into your hand, hovering over a right or left), swipe your arm the competitive sporting action. labelled area of the screen across your body. Split into two teams and nominate until it fills up. players for head-to-head battles while the game tracks your victories. Take on computer GAME MENUS opponents if you’re playing alone. To bring up the Pause menu, hold your left arm out diagonally at around 45° from your body until the Kinect Warranty For Your Copy of Xbox Game Software (“Game”) Acquired in Australia or Guide icon appears. Be sure to face the sensor straight New Zealand on with your legs together and your right arm at your IF YOU ACQUIRED YOUR GAME IN AUSTRALIA OR NEW ZEALAND, THE FOLLOWING side. From this menu you can quit, restart, or access WARRANTY APPLIES TO YOU IN ADDITION the Kinect Tuner if you experience any problems with TO ANY STATUTORY WARRANTIES: Consumer Rights the sensor (or press on an Xbox 360 controller if You may have the benefi t of certain rights or remedies against Microsoft Corpor necessary).