Interventions to Reduce Unplanned Hospital Admission:A Series of Systematic Reviews Page 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme Enhancing Clinical Research Across the Globe

RCN International Nursing Research Conference and Exhibition 2019 Tuesday 3 - Thursday 5 September 2019 Sheffield Hallam University, UK Conference brochure kindly supported by media partner Accrue up to 27 hours #research2019 of CPD PATIENT STATUS Visit EDGE on stand 8 THE POWER OF DATA For everyone. Anywhere. In real-time. EDGE. Intelligent Research ManagementTM An innovative programme enhancing clinical research across the globe [email protected] www.edgeclinical.com Welcome 5 Acknowlegements and thanks 6 International Scientific Advisory Panel 7 General information 8 Venue Plan 10 Exhibitor listing 11 Programme Tuesday 3 September 13 Wednesday 4 September 18 Thursday 5 September 23 Posters Tuesday 3 September 28 Wednesday 4 September 29 Thursday 5 September 30 Royal College of Nursing 20 Cavendish Square London W1G 0RN rcn.org.uk 007 698 | August 2019 3 Library and Archive Service Exhibitions and events programme 24-hour access to thousands of e-books and e-journals at rcn.org.uk/library Help and advice on searching Libraries in Belfast, for information Cardiff, Edinburgh and London www.rcn.org.uk/library 0345 337 3368 @rcnlibraries @rcnlibraries 4 Library and Archive Service Welcome The theme of this year’s conference is the impact of nursing research. This is very fitting as 2019 is the Exhibitions and 60th year in which there has been a meeting of nurses to share their research and meet like-minded events programme colleagues. The first such meeting took place in the RCN headquarters in London in 1959 as a research discussion group attended by Doreen Norton, Winifred Raphael, Gertrude Ramsden, Muriel Skeet and Lisbeth Hockey. -

School of Health Sciences Nursing Careers

For general enquiries School of Health Sciences School of Health Sciences please contact: t: +44 (0)115 823 0850 e: [email protected] Nursing Careers w: www.nottingham.ac.uk/healthsciences www.nottingham.ac.uk/healthsciences Nursing Careers Nursing Careers Contents Introduction The NHS is committed to offering development and learning opportunities for all full- and part- Congratulations on pursuing a career in time staff. You will receive an annual personal 02 Introduction healthcare! development review and development plan to support your career progression and, as part of 03 The Career Framework Once you have qualified as a nurse and as your the Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF), within 05 Models of study healthcare career develops, you will have the Agenda for Change, you will be encouraged to opportunity to move into different areas and extend your range of skills and knowledge and 07 Jobs responsibilities. take on new responsibilities. Nurses form the largest group of staff in the NHS For information on the Knowledge and Skills and are a crucial part of the healthcare team. Framework go to Outside of the NHS, opportunities exist within www.nhs.employers.org/agendaforchange the independent and charitable sectors, including private hospitals, clinics, nursing homes and organisations such as Macmillan Cancer Support. Nurses are also in high-demand from the armed forces. Nurses work in every sort of health setting, from accident and emergency to working in the community, in patients’ homes, or schools, with people of all ages and backgrounds. 01 www.nottingham.ac.uk/healthsciences www.nottingham.ac.uk/healthsciences 02 Nursing Careers Nursing Careers The diagram below gives an illustration of a variety of NHS careers The Career Framework and where they may fit on the career framework. -

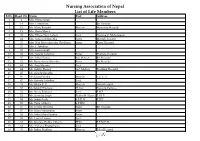

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Lawrlwytho'r Atodiad Gwreiddiol

Operational services structure April 2021 14/04/2021 Operational Leadership Structures Director of Operations Director of Nursing & Quality Medical Director Lee McMenamy Joanne Hiley Dr Tessa Myatt Medical Operations Operations Clinical Director of Operations Deputy Director of Nursing & Deputy Medical Director Hazel Hendriksen Governance Dr Jose Mathew Assistant Clinical Director Assistant Director of Assistant Clinical DWiraerctringor ton & Halton Operations Corporate Corporate Lorna Pink Assistant Assistant Director Julie Chadwick Vacant Clinical Director of Nursing, AHP & Associate Clinical Director Governance & Professional Warrington & Halton Compliance Standards Assistant Director of Operations Assistant Clinical Director Dr Aravind Komuravelli Halton & Warrington Knowsley Lee Bloomfield Claire Hammill Clare Dooley Berni Fay-Dunkley Assistant Director of Operations Knowsley Associate Medical Director Nicky Over Assistant Clinical Director Allied Health Knowsley Assistant Director of Sefton Professional Dr Ashish Kumar AssiOstapenrta Dtiironesc tKnor oofw Oslpeeyr ations Sara Harrison Lead Nicola Over Sefton James Hester Anne Tattersall Assistant Clinical Director Associate Clinical Director Assistant Director of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients St Helens Operations Sefton Debbie Tubey Dr Raj Madgula AssistanAt nDniree Tcatttore ofrs aOllp erations Head of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients Safeguarding Tim McPhee Assistant Clinical Director Sarah Shaw Assistant Director of Associate Medical Director Operations St Helens Mental Health -

Nursing Today

JF»%, NURSING TODAY MSN (UBC), who joins the 3rd year team as NEWS ITEMS an Instructor II. Born in Edmonton, she recently completed her MSN in the School and previously has had clinical and NEW FACULTY JOIN SCHOOL teaching experience in Edmonton. SALLY THORNE, BSN (UBC), MSN (UBC), Eight new faces will be seen around who joins the 2nd year team as Instructor the School of Nursing this fall. Please II. A British-born Canadian, she is join in welcoming: well-known to the School as she was a LINDA BEECHINOR, BSN (Calgary), who Lecturer before entering the MSN program. joins the 2nd year team as a Sessional Lecturer. A native of Ottawa, she has taught in basic nursing programs in Kelowna NURSE-SOCIOLOGIST CHAIRS SYMPOSIUM AT and Burnaby. INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS MARILYN DEWIS, BSN (Toronto), MEd (Ottawa), who joins the 4th year team as Dr. Joan Anderson organized and Assistant Professor. A native of Toronto, chaired a two-day symposium on "The Rele her most recent position before her move to vance of the Social Sciences to Health UBC was Assistant Professor in the Care" at the Xlth International Congress of University of Ottawa School of Nursing. Her Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences area of interest and expertise is held in Vancouver in August. The symposium medical-surgical nursing. brought together scholars from several dif VALERIE LESLIE, BSN (UBC), who joins ferent parts of the world, including the 1st year team as a Sessional Lecturer. Nigeria, Hong Kong, Singapore, Europe, She has had clinical experience in various British Isles, United States and Canada. -

THE DEVELOPMENT of NURSING EDUCATION in the ENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN ISLANDS by PEARL I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NURSING EDUCATION IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN ISLANDS by PEARL I. GARDNER, B.S.N., M.S.N., M.Ed. A DISSERTATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approved Accepted Dean of the Graduate School August, 1993 ft 6 l^yrr^7^7 801 J ,... /;. -^o ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS C?^ /c-j/^/ C^ ;^o.^^ I would like to thank Dr. Clyde Kelsey, Jr., for his C'lp '^ ^unflagging support, his advice and his constant vigil and encouragement in the writing of this dissertation. I would also like to thank Dr. Patricia Yoder-Wise who acted as co-chairperson of my committee. Her advice was invaluable. Drs. Mezack, Willingham, and Ewalt deserve much praise for the many times they critically read the manuscript and gave their input. I would also like to thank Ms. Janey Parris, Senior Program Officer of Health, Guyana, the government officials of the Caribbean Embassies, representatives from the Caribbean Nursing Organizations, educators from the various nursing schools and librarians from the archival institutions and libraries in Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica. These individuals agreed to face-to-face interviews, answered telephone questions and mailed or faxed information on a regular basis. Much thanks goes to Victor Williams for his computer assistance and to Hannelore Nave for her patience in typing the many versions of this manuscript. On a personal level I would like to thank my niece Eloise Walters for researching information in the nursing libraries in London, England and my husband Clifford for his belief that I could accomplish this task. -

Design and Implementation of Health Information Systems

Design and implementation of health information systems Edited by Theo Lippeveld Director of Health Information Systems, John Snow Inc., Boston, MA, USA Rainer Sauerborn Director of the Department of Tropical Hygiene and Public Health, University of Heidelberg, Germany Claude Bodart Project Director, German Development Cooperation, Manila, Philippines World Health Organization Geneva 2000 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Design and implementation of health information systems I edited by Theo Lippeveld, Rainer Sauerborn, Claude Bodart. 1.1nformation systems-organization and administration 2.Data collection-methods I.Lippeveld, Theo II.Sauerborn, Rainer III.Bodart, Claude ISBN 92 4 1561998 (NLM classification: WA 62.5) The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its pub lications, in part or in full. Applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Office of Publi cations, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. © World Health Organization 2000 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Or ganization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

How Health Visitors Understand the Social

Making a difference: how health visitors understand the social processes of leadership STANSFIELD, Karen Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23238/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version STANSFIELD, Karen (2017). Making a difference: how health visitors understand the social processes of leadership. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Making a Difference: How Health Visitors Understand the Social Processes of Leadership Karen Stansfield A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration August 2017 Abstract Leadership has become a pre-requisite for all health professionals working at every level in healthcare. The need to strengthen leadership in health visiting has been voiced in health care policy for the past eighteen years (Department of Health (DH), 1999 & 2006; National Health Service (NHS) England, 2016). Yet there is still a lack of research examining how health visitors understand leadership, with, much of the existing research on leadership focusing on leaders “per se” as opposed to leadership as a social process. This study sought to understand how health visitors perceive their leadership role, and how leadership is demonstrated in the delivery of the health visiting service in the context of the NHS. The aim being to enable the researcher to examine how health visitors understand leadership as a social process. -

JNR0120SE Globalprofile.Pdf

JOURNAL OF NURSING REGULATION VOLUME 10 · SPECIAL ISSUE · JANUARY 2020 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE BOARDS OF NURSING JOURNAL Volume 10 Volume OF • Special Issue Issue Special NURSING • January 2020 January REGULATION Advancing Nursing Excellence for Public Protection A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice National Council of State Boards of Nursing Pages 1–116 Pages JOURNAL OFNURSING REGULATION Official publication of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Editor-in-Chief Editorial Advisory Board Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN Mohammed Arsiwala, MD MT Meadows, DNP, RN, MS, MBA Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation President Director of Professional Practice, AONE National Council of State Boards of Nursing Michigan Urgent Care Executive Director, AONE Foundation Chicago, Illinois Livonia, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Chief Executive Officer Kathy Bettinardi-Angres, Paula R. Meyer, MSN, RN David C. Benton, RGN, PhD, FFNF, FRCN, APN-BC, MS, RN, CADC Executive Director FAAN Professional Assessment Coordinator, Washington State Department of Research Editors Positive Sobriety Institute Health Nursing Care Quality Allison Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN Adjunct Faculty, Rush University Assurance Commission Brendan Martin, PhD Department of Nursing Olympia, Washington Chicago, Illinois NCSBN Board of Directors Barbara Morvant, MN, RN President Shirley A. Brekken, MS, RN, FAAN Regulatory Policy Consultant Julia George, MSN, RN, FRE Executive Director Baton Rouge, Louisiana President-elect Minnesota Board of Nursing Jim Cleghorn, MA Minneapolis, Minnesota Ann L. O’Sullivan, PhD, CRNP, FAAN Treasurer Professor of Primary Care Nursing Adrian Guerrero, CPM Nancy J. Brent, MS, JD, RN Dr. Hildegarde Reynolds Endowed Term Area I Director Attorney At Law Professor of Primary Care Nursing Cynthia LaBonde, MN, RN Wilmette, Illinois University of Pennsylvania Area II Director Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lori Scheidt, MBA-HCM Sean Clarke, RN, PhD, FAAN Area III Director Executive Vice Dean and Professor Pamela J. -

Evaluation of Hospital Information System in the Northern Province in South Africa

EVALUATION OF HOSPITAL INFORMATION SYSTEM IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE IN SOUTH AFRICA “ Using Outcome Measures” Report prepared for the HEALTH SYSTEMS TRUST By Nolwazi Mbananga Rhulani Madale Piet Becker THE MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA PRETORIA May 2002 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Department of Health and Welfare in the Northern Province is acknowledged for its mandate to conduct this study and its support of the project throughout. The project Team is recognised for its great efforts in developing the project proposal and obtaining the necessary funding to conduct the study, without which it would not have been possible. The project team members; Dr Jeremy Wyatt, Dr LittleJohns, Dr Herbst, Dr Zwarenstein, Dr Power, Dr Rawlinson, Dr De Swart, Dr P Becker, Ms Madale and others played a key role in maintaining the scientific rigour for the study and their dedication is appreciated. The MEDUNSA Community Health in the Northern Province is credited for the direction and support it provided during the early stages of project development, planning and implementation. It is important to explain that Ms Mbananga conducted the qualitative component of the study as a Principal investigator while she and Dr Becker were called upon to take over the quantitative component of the study and joined at the stage of post implementation data collection. The financial support that was provided by the Health Systems Trust and the Medical Research Council is highly valued this project could not have been started and successfully completed without it. We cannot forget our secretaries: Emily Gomes and Alta Hansen who assisted us in transcribing data. -

The Matron's Handbook

The matron’s handbook For aspiring and experienced matrons Updated July 2021 Contents Foreword........................................................................................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................... 4 The matron’s key roles................................................................... 6 1. Inclusive leadership, professional standards and accountability 8 2. Governance, patient safety and quality .................................... 12 3. Workforce planning and resource management ...................... 17 4. Patient experience and reducing health inequalities ................ 22 5. Performance and operational oversight ................................... 24 6. Digital and information technology ........................................... 27 7. Education, training and development ....................................... 33 8. Research and development ..................................................... 36 9. Collaborative working and clinical effectiveness ...................... 37 10. Service improvement and transformation .............................. 40 Appendix: The matron’s developmental framework and competencies............................................................................... 43 Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 51 1 | Contents Foreword Matrons are vital to delivering high quality care to patients and their relatives across the NHS and the wider health and care sector. They -

Divisional Structure - University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust – As at 1 July 2021

Divisional structure - University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust – as at 1 July 2021 Chief operating officer Joe Teape Division A Division B Division C Division D DCD – Andrew Webb DCD – Trevor Smith DCD – Freya Pearson DCD – David Higgs DDO – Greg Chapple DDO – Gavin Hawkins DDO – Martin De Sousa DHN/P – Rachel Davies DHN/P – Sarah Herbert DDO – Jacqui McAfee DHN/P – Louisa Green DHN/P – Natasha Watts Acuity Matron – Karen Hill DR&DL – Fraser Cummings DoM – Suzanne Cunningham DR&DL – Boyd Ghosh DR&DL – Bhaskar Somani DFM – John Light DR&DL – Luise Marino DFM – Alex Mawers (Interim) DS&BDM – Alison Gray DFM – Wayne Rogers DFM – Emma Hawkins DS&BDM – Adam Wells HRBP – Emma Watts DS&BDM – Dan Jeffery DS&BDM – Victoria Kearney HRBP – Rachel Dore HRBP – Rachel Dore (covering until replacement) Care groups HRBP – Katie Dunman (nee Molloy) Care groups Cancer care: Care groups Care groups Surgery: CGCL – Tim Iveson Women and newborn: Cardiovascular and thoracic: CGCL – John Knight CGM – Collette Byelong CGCL – Sarah Walker CGCL – Edwin Woo CGM – Justin Sanders (from 5/7/21) A/CGM – awaiting appointment CGM – Fiona Lawson CGM – Fiona Liddell A/CGM – Jon Watson Matron – Jenny Milner IP & Theatres Matron – Carol Gosling ACGM – Juliet Thomas A/CGM – Erin Flahavan Matron – Steph Churchill OP Matron – Karen Elkins Matron – Jenny Dove Neonatal Matron – Andrea Robson (interim) Matron – Kerry Rayner Matron – Julia Tonks Matron – Georgina Kirk Angie Ansell (from 12/7/21) Emergency medicine: Matron - Jean-Paul Evangelista Matron – Jo Rigby CGCL