Aviation and Amphibian Engineers in the Southwest Pacific by William C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center John Ingersoll 1625-1684 Bedfordshire, England Jonathan Ingersoll 1681-1760 Connecticut __________________________________________ Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll Jared Ingersoll 1713-1788 1722-1781 Ridgefield, Connecticut Stampmaster General for N.E Chaplain Colonial Troops Colonies under King George III French and Indian Wars, Champlain Admiralty Judge Grace Isaacs m. Jonathan Ingersoll Baron J.C. Van den Heuvel Jared Ingersoll, Jr. 1770-1823 1747-1823 1749-1822 Lt. Governor of Conn. Member Const. Convention, 1787 Judge Superior and Supreme Federalist nominee for V.P., 1812 Courts of Conn. Attorney General Presiding Judge, District Court, PA ___ _____________ Grace Ingersoll Charles Anthony Ingersoll Ralph Isaacs Ingersoll m. Margaret Jacob A. Charles Jared Ingersoll Joseph Reed Ingersoll Zadock Pratt 1806- 1796-1860 1789-1872 1790-1878 1782-1862 1786-1868 Married General Grellet State=s Attorney, Conn. State=s Attorney, Conn. Dist. Attorney, PA U.S. Minister to England, Court of Napoleon I, Judge, U.S. District Court U.S. Congress U.S. Congress 1850-1853 Dept. of Dedogne U.S. Minister to Russia nom. U.S. Minister to under Pres. Polk France Charles D. Ingersoll Charles Robert Ingersoll Colin Macrae Ingersoll m. Julia Helen Pratt George W. Pratt Judge Dist. Court 1821-1903 1819-1903 New York City Governor of Conn., Adjutant General, Conn., 1873-77 Charge d=Affaires, U.S. Legation, Russia, 1840-49 Theresa McAllister m. Colin Macrae Ingersoll, Jr. Mary E. Ingersoll George Pratt Ingersoll m. Alice Witherspoon (RI=s father) 1861-1933 1858-1948 U.S. Minister to Siam under Pres. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

Right Man for the Job Colonel Charles H. Karlstad by Michael E. Krivdo Vol. 8 No. 1 76 n mid-1952, the Army’s senior Psychological Warfare General Agriculture in 1917. Soon after Congress declared (Psywar) officer, Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. war on Germany in April 1917, a Regular Officer Board IMcClure, faced a dilemma. As head of the Office of the selected Karlstad as one of 10,000 candidates to become Chief of Psychological Warfare (OCPW), he had finally officers in a planned expansion of the military. He reported secured permission to create a center and school for both to Fort Snelling, Minnesota, in May 1917 to attend the First Psywar and Special Forces (SF). Now he needed the right Officer Training Camp. Three months later, he accepted man to bring this project to fruition, an officer with a solid a reserve commission as a second lieutenant of Infantry.3 reputation and the perfect combination of Army Staff As one of the first new officers in a rapidly expanding and schools experience to man, fund, and resource it to army, Karlstad found himself tasked with training tens make it operational. This task was daunting; the man of thousands of Americans joining the armed forces. chosen would be commander of the forces assigned to the Reporting to the 88th Infantry Division (ID) at Camp Center, Psywar and SF units, and the school commandant Dodge, a National Army post that had sprung up almost who trained and educated officers and soldiers assigned overnight on the outskirts of Des Moines, Iowa, the to those units. -

SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California

Undergraduate Catalog of Courses Volume 2010 2010-2011 Article 44 7-1-2010 SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog Recommended Citation Saint Mary's College of California (2010) "SECTION II," Undergraduate Catalog of Courses: Vol. 2010 , Article 44. Available at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog/vol2010/iss1/44 This Section II is brought to you for free and open access by Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Catalog of Courses by an authorized editor of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. diversity requirement courses Students may satisfy the Diversity Requirement by taking one course from the list of approved courses; other courses, depending on content, may satisfy the requirement but require a petition. Students who complete the four-year curriculum in the Integral Program or in the Liberal and Civic Studies Program satisfy the requirement without additional coursework. Students who withdraw from either program should consult their advisor about the requirement. 173 Diversity Requirement Courses APPROVED DIVERSITY COURSES DIVERSITY REQUIREMENT BY PETITION AH 025 Survey of Asian Art In addition to the courses which automatically satisfy the requirement, Anthropology 001 Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology the following courses may sometimes satisfy the Diversity Requirement, Anthropology 111 Kinship, Marriage and Family depending on the content of the course in a given semester. Students Anthropology 112 Race and Ethnicity who wish to apply one of these courses (or any other course not listed Anthropology 113 Childhood and Society on this page) to satisfy the Diversity Requirement must do so through Anthropology 117 Religion, Ritual, Magic and Healing a petition to the Registrar’s Office and permission of the chair of the Anthropology 119 Native American Cultures department in which the course is housed. -

REGISTER Portion O F Tne Seminary

$54,000 Building Planned at S t Thomas’ Seminary Striking Cancer Cure Ascribed to St. Cabrini Workers' Residence Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Will Release Space Pilgrimage Honoring Beloved Contents Copyrighted bjr the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1948— Permission to Reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue. For More Students Plans are being drawn for a structure at St. Thomas’ Denver Foundress Is July 11 seminary, Denver, to house workers at the institution. The building will be used eventually by sisters, who will be se Mother Cabrini “times” her miracles. DENVER CATHOUC cured to care for the domestic duties of the institution. It will Yesterday, July 7, was the second anniversary of her canonization. Sunday, July 11, not be possible to get any nuns this year, believes the Very Catholics of Denver and Colorado will wend their way to her mountain shrine for the sec Rev. Francis Keeper, C.M., president, but the building w’ill be ond annual pilgrimage in her honor. ready for use by early fall. And yesterday, as if to give impetus to the celebration Sunday, it was revealed that a The edifice will be of buff brick I man, condemned to die as a victim of a hopeless cancer of the throat, will soon be dis with a red tile roof of the same charged from Fitzsimons General hospital as a "cured” patient__________________________ style and appearance as the new The cancer victim, whose cure REGISTER portion o f tne seminary. Its costj Bishop Calls IS ascribed to the intercession of Will Conduct when completed is estimated at St. -

SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California

Undergraduate Catalog of Courses Volume 2007 2007-2008 Article 43 7-1-2007 SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog Recommended Citation Saint Mary's College of California (2007) "SECTION II," Undergraduate Catalog of Courses: Vol. 2007 , Article 43. Available at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog/vol2007/iss1/43 This Section II is brought to you for free and open access by Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Catalog of Courses by an authorized editor of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Students may satisfy the Diversity Requirement by taking one course from the list of approved courses; other courses, depending on content, may satisfy the requirement but require a petition. Students who complete the four-year curriculum in the Integral Program or in the Liberal and Civic Studies Program satisfy the requirement without additional courseworl<. Students who w ithdraw from either program should consult their advisor about the requirement 163 Diversity Requirement Courses APPROVED DIVERSITY COURSES DIVERSITY REQUIREMENT BY PETITION AH 025 Survey of Asian Art In addition to the courses which automatically satisfy the requirement. Anthropology 00 I Introduction to Social and Cultural Anthropology the following courses may sometimes satisfy the Diversity Requirement, Anthropology Ill Kinship, Marriage and Family depending on the content of the course in a given semester. Students Anthropology I 12 Race and Ethnicity who wish to apply one of these courses (or any other course not listed Anthropology I 13 Childhood and Society on this page) to satisfy the Diversity Requirement must do so through Anthropology I 16 New Immigrants and Refugees a petition to the Registrar's Office and permission of the chair of the Anthropology 117 Religion, Ritual, Magic and Healing department in which the course is housed. -

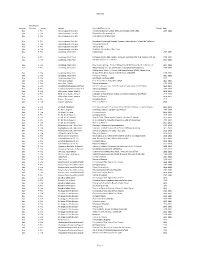

Location Box/Album Number Format Subject Expanded Description

DEVERS Box/Album Location Number Format Subject Expanded Description Month Year Box 1 File Genealogy and Early Life French and German Letters-Most untranslated 1809-1882 1809- 1882 Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life Biographies--For publication Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life Early Life Prior to West Point Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life Genealogy Charts and Records, Directory Listing Devers, "Would-Be" Relatives Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life Genealogy Research Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life Transcript file Box 2 File Genealogy and Early Life York High School--After West Point Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Cadet Prayer 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Correspondence, 1905- 1909; J. L. Devers, West Point to Ira D. Weiser, York, PA 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Detailed Service of J. L. Devers 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Newspaper clippings, Funeral of King Edward VII, Troops March in Procession 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Patton Papers, The - by: Blumenson ; Excerpt concerning Devers 1905- 1909 Photographs, Mrs. P. K. Devers Visits Cadet Devers, 8/1905; Cadet Camp, Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Hudson River, Dress Parade at West Point; 1906/1907 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point Transcript Extracts 1905- 1909 Box 3 File Cadetship, West Point West Point Yearbook, 1909 1909 Box 4 File Army War College Courses Studied at Army War College 1932- 1933 Box 4 File Army War College Transcript Extracts 1932- 1933 Box 4 File Command and General Staff Sch Roll of Graduates, Class 1924-25 Command and General Staff School 1924- 1925 Box 4 File Command and General Staff Sch Transcript Extracts 1924- 1925 Box 4 File Fld Artillery Tactics, West Pt Correspondence 1919- 1924 Box 4 File Fld Artillery Tactics, West Pt Instructor of Field Artillery Tactics, US Military Academy, West Point 1919- 1924 Box 4 File Fld Artillery Tactics, West Pt Transcript Extracts 1919- 1924 Box 4 File France - Germany Correspondence 1919 Box 4 File France - Germany Transcript Extracts 1919 Box 4 File Ft. -

Priest Offered Commission As Captain in National Guard

PRIEST OFFERED COMMISSION AS CAPTAIN IN NATIONAL GUARD NATIONAL B O A R D HAS NOT ACTED ON Pray for the Get Your Nexf- Father Donovan Cannot Success of the DoorNeighhor K. OF C. SANITARIUM, Cathotic Press to Subscribe SAYS JOHN H. REDDIN Accept; Will be Chaplain -sS> , V Subject for Supreme Council, FOUNDER OF CHURCH Not for Directors, TWO PRIESTS AMONG He Declares. IN EL PASO LEAVES FIRST RECRUITS IN IT HAS BEEM UP BEFORE CITY A H E R M A N Y He Suggests That a Definite K. OF C. COMPANY New Plan be Worked- YEARS OF SERVICE Out. DENVER IS F O R IN G VOL. XII. NO. 39. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, MAY 3, 1917. $2 PER YEAR. A newspaper report sent out from Father Pinto Put Up a Sur Washington indicating that there was Father Mannix and Saint Philo- opposition on the part of the national prising Number of mena’s Rector Show hoard of directors of the Knights of CATHOUC GIRL CHRISTENS GIANT NEW DREADNAUGHT Buildings. Patriotism. Columbus to the project recently starteil in Denver to get a tuberculosis sanitari um for the order, was denied yesterday FORMERLY COLORADO NAMES ARE ANNOUNCED » ■ 40 by John H. Reddin, supreme master of the Fourt Degree and a national director, ’ ’ < •‘A,; s ' ' Erected Holy Trinity Church at Men Stand Ready; Pull Quota who recently returned from the meeting Trinidad Before Going in the capital city. Is Expected Within a South. Mr. Rtsldin pointed out that, while M H a ' v li s V X ^ s Few Days. -

MCGILL, RALPH. Ralph Mcgill Papers, 1853-1971

MCGILL, RALPH. Ralph McGill papers, 1853-1971 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: McGill, Ralph. Title: Ralph McGill papers, 1853-1971 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 252 Extent: 65.375 linear feet (124 boxes), 75 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 6 oversized papers boxes and 3 oversized papers folders (OP), 2 framed items (FR), 7 microfilm reels (MF), AV Masters: 5.75 linear feet (7 boxes, 1 LP box, and 1 film) Abstract: Papers of Atlanta jounalist and editor Ralph McGill including correspondence, writings, subject files, committee and foundation records, scrapbooks, photographs, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Researchers are required to use the microfilm copy of Scrapbooks 18-73 in Series 9. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance for access to audiovisual materials in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance for access to unprocessed born digital materials in this collection. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to unprocessed born digital materials. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Videotapes in Subseries 14.5 may not be used for or included in any film, video, or television program without written permission. Additional Physical Form Daily editorial column clipping in Scrapbooks 18-73 in Series 9 are also available on microfilm. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California

Undergraduate Catalog of Courses Volume 2012 2012-2013 Article 43 7-1-2012 SECTION II Saint Mary's College of California Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog Recommended Citation Saint Mary's College of California (2012) "SECTION II," Undergraduate Catalog of Courses: Vol. 2012 , Article 43. Available at: http://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/undergraduate-catalog/vol2012/iss1/43 This Section II is brought to you for free and open access by Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Catalog of Courses by an authorized editor of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Administration ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS COUNSEL Brother Ronald Gallagher, FSC, Ph.D. Larry Nuti, J.D. President College Counsel Bethami A. Dobkin, Ph.D. Provost/Vice President for Academic Affairs ACADEMIC SCHOOL DEANS Michael Beseda, M.A. Zhan Li, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Enrollment and Dean of the School of Economics and Vice President for College Communications Business Administration Keith Brant, Ph.D. Phylis Metcalf-Turner, Ph.D. Vice President for Development Dean of the Kalmanovitz School of Education Jane Camarillo, Ph.D. Roy Wensley, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Student Life Dean of the School of Science Peter Michell, M.A. Stephen Woolpert, Ph.D. Vice President for Finance Dean of the School of Liberal Arts Carole Swain, Ph.D. Vice President for Mission ACADEMIC ADMINISTRATORS Christopher Sindt, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Studies Shawny Anderson, Ph.D. Associate Dean, School of Liberal Arts Richard M. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES States

6798 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE AUGUST 10 Col. Jerry Vrchlicky Matejka (lieutenant IN THE MARINE CORPS colonel, Signal Corps), Army of the United Brig. Gen. (temporary) Allen H. Turnage, HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES States. now serving under a temporary commission . Col. Ray Edison Porter (lieutenant colonel, for a specified duty, to be a brigadier gen MoNDAY, AuGusT 10, 1942 Infantry), Army of the United States. eral in the Marine Corps for temporary serv Col. Albert Charles Stanford (lieutenant ice for general duty from the 29th day of The House met at 12 noon. colonel, Field Artillery), Army of the United March 1942. Rev. Bernard Braskamp, D. D., pastor States. Brig. Gen. (temporary) Ralph J. Mitchell, of the Gunton Temple Memorial Pres Col. Claudius Miller Easley (lieutenant col now serving under a temporary commission byterian Church, Washington, D. C., of onel, Infantry), Army of the United States. for a specified duty, to be a brigadier general fered the following prayer: . Col. Benjamin Franklin Giles (lieutenant in the Marine Corps for temporary service colonel, Air Corps; temporary colonel, Air for general duty from the 30th day of March 0 Thou who hast dispelled the dark Corps), Army of the United States. 1942. ness of the night and illumined the earth Col. Frank Watkins Weed, Medical Corps. Col. Bennet Puryear, Jr., assistant quarter Col. Edgar Lewis Clewell (lieutenant colonel, with the radiant glory of a new day, we master, to be an assistant quartermaster in are lifting our hearts and voices in glad Signal Corps). Army of the United States. the Marine Corps with the rank of brigadier Col. -

464 Congressional Record-Senate

464 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE JANUARY 23 SELECT COMMITI'EE ON SMALL BUSINESS, form the duties of the Chair during my also hold public hearings on Friday, Jan HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES .absence. uary 30, 194<3, at 10:30 a. m., on Senate Januar y 23, 1948 (cor rected from Janu ary A. H. VANDENBERG, bill 1651 , to amend the General Bridge 12, 1948) Presi dent pro tempore. Act of 1946. All interested parties will , To THE CLERK oF THE HousE: Mr. CAIN thereupon took the chair as be afforded the opportunity to be heard .. The above-ment ioned committee or sub Acting President pro tempore. concerning these bills. Witnesses are re commit tee, pursuant to section 134 (b) of THE JOURNAL quested to file with the committee writ the Legislat ive Reorga nization Act of 1946, ten statements of their proposed testi Public Law 601, Seventy-ninth Congress, ap On request of Mr. WHERRY, and by proved August 2, 1946, as amended, submits mony at least 3 days in advance of the unanimous consent, the reading of the hearings. the following report showing the name, pro Journal of the proceedings of Wednes fession, aJ1d total salary of each pe!'son em LEAVES OF ABSENCE ployed by it for the period from July 1, 1947, day, January 21, 1948, was dispensed to and including December 31, 1947, together with, and the Journal was approved. Mr. BALDWIN. Mr. President, I have with funds if authorized or appropriated to .MESSAGES FROM THE PRESIDENT a very important meeting to attend in and expended by it: Connecticut tonight and I ask unani Messages in writing from the President mous consent to be absent from the Sen of the United States submitting nomina Total ate after 12:30 p. -

Postwar Philippine Trials of Japanese War Criminals in History and Memory

JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION: POSTWAR PHILIPPINE TRIALS OF JAPANESE WAR CRIMINALS IN HISTORY AND MEMORY by Sharon Williams Chamberlain BA, 1971, Bucknell University MA, 1979, University of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2010 Dissertation directed by Shawn McHale Associate Professor of History and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Sharon Williams Chamberlain has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 24, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION: POSTWAR PHILIPPINE TRIALS OF JAPANESE WAR CRIMINALS IN HISTORY AND MEMORY Sharon Williams Chamberlain Dissertation Research Committee: Shawn McHale, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Daqing Yang, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member Edward A. McCord, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2010 by Sharon Williams Chamberlain All rights reserved iii Dedication To Mary Morrow Chamberlain and Richard Williams Chamberlain iv Acknowledgments I wish to thank the chair of my dissertation committee, Shawn McHale, for his encouragement, good counsel, and thought-provoking insights as I undertook this long but satisfying journey. The (for me) entirely fortuitous decision to take Professor McHale’s excellent graduate seminar on Modern Southeast Asia opened up possibilities beyond the study of Japan and led me to the exploration of Japan-Philippine relations and thence to the subject of this dissertation.