The Other "Parthenon": Antiquity and National Memory at Makronisos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

DESERTMED a Project About the Deserted Islands of the Mediterranean

DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean The islands, and all the more so the deserted island, is an extremely poor or weak notion from the point of view of geography. This is to it’s credit. The range of islands has no objective unity, and deserted islands have even less. The deserted island may indeed have extremely poor soil. Deserted, the is- land may be a desert, but not necessarily. The real desert is uninhabited only insofar as it presents no conditions that by rights would make life possible, weather vegetable, animal, or human. On the contrary, the lack of inhabitants on the deserted island is a pure fact due to the circumstance, in other words, the island’s surroundings. The island is what the sea surrounds. What is de- serted is the ocean around it. It is by virtue of circumstance, for other reasons that the principle on which the island depends, that the ships pass in the distance and never come ashore.“ (from: Gilles Deleuze, Desert Island and Other Texts, Semiotext(e),Los Angeles, 2004) DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean Desertmed is an ongoing interdisciplina- land use, according to which the islands ry research project. The “blind spots” on can be divided into various groups or the European map serve as its subject typologies —although the distinctions are matter: approximately 300 uninhabited is- fluid. lands in the Mediterranean Sea. A group of artists, architects, writers and theoreti- cians traveled to forty of these often hard to reach islands in search of clues, impar- tially cataloguing information that can be interpreted in multiple ways. -

Hamilakis Nation and Its Ruins.Pdf

CLASSICAL PRESENCES General Editors Lorna Hardwick James I. Porter CLASSICAL PRESENCES The texts, ideas, images, and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome have always been crucial to attempts to appropriate the past in order to authenticate the present. They underlie the mapping of change and the assertion and challenging of values and identities, old and new. Classical Presences brings the latest scholarship to bear on the contexts, theory, and practice of such use, and abuse, of the classical past. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece YANNIS HAMILAKIS 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Yannis Hamilakis 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Bad Blood: Contemporary British Novels and the Cyprus Emergency

EMERGING FROM THE OPPRESSIVE SHADOW OF MYTH: ORESTES IN SARTRE, RITSOS, AND AESCHYLUS* Maria Vamvouri Ruffy In this article I compare Orestes by Yannis Ritsos and The Flies by Jean-Paul Sartre with Aeschylus’s Choephori. In Ritsos’s and Sartre’s works, written in a context of censorship and political oppression, a problematic relationship with the past weighs on the protagonist to the extent that he desires to free himself from it. The contemporary Orestes detaches himself from the path set out by a usurping power belonging to the past, a path used to manipulate individuals and to block the way to freedom. In Ritsos’s Orestes the speaker breaks from the ideal of antiquity, while in The Flies, it is not the past but rather the present circumstances that motivate Orestes to act freely. I read the protagonist’s problematic relationship with the past as a mise en abîme of the critical distance of one (re)writing in relation to another and I compare all three texts from the point of view of the singular relationship maintained by the protagonist with his past. ny (re)writing of a myth involves a critical engagement with intertexts on which it casts a new light and from which it Asometimes seeks to detach or free itself.1 At the same time, a (re)writing often says something about the pragmatic context of its production. It is through this critical engagement with its intertexts, and through the anachronisms and metaphors juxtaposing the past and the present, that the (re)writing enhances or questions its own context of production. -

Königs-Und Fürstenhäuser Aktuelle Staatsführungen DYNASTIEN

GESCHICHTE und politische Bildung STAATSOBERHÄUPTER (bis 2019) Dynastien Bedeutende Herrscher und Regierungschefs europ.Staaten seit dem Mittelalter Königs-und Fürstenhäuser Aktuelle Staatsführungen DYNASTIEN Römisches Reich Hl. Römisches Reich Fränkisches Reich Bayern Preussen Frankreich Spanien Portugal Belgien Liechtenstein Luxemburg Monaco Niederlande Italien Großbritannien Dänemark Norwegen Schweden Österreich Polen Tschechien Ungarn Bulgarien Rumänien Serbien Kroatien Griechenland Russland Türkei Vorderer Orient Mittel-und Ostasien DYNASTIEN und ihre Begründer RÖMISCHES REICH 489- 1 v.Chr Julier Altrömisches Patriziergeschlecht aus Alba Longa, Stammvater Iulus, Gaius Iulius Caesar Julisch-claudische Dynastie: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero 69- 96 n.Ch Flavier Röm. Herrschergeschlecht aus Latium drei römische Kaiser: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian 96- 180 Adoptivkaiser u. Antonionische Dynastie Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Mark Aurel, Commodus 193- 235 Severer Aus Nordafrika stammend Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabal, Severus Alexander 293- 364 Constantiner (2.flavische Dynastie) Begründer: Constantius Chlorus Constantinus I., Konstantin I. der Große u.a. 364- 392 Valentinianische Dynastie Valentinian I., Valens, Gratian, Valentinian II. 379- 457 Theodosianische Dynastie Theodosius I.der Große, Honorius, Valentinian III.... 457- 515 Thrakische Dynastie Leo I., Majorian, Anthemius, Leo II., Julius Nepos, Zeno, Anastasius I. 518- 610 Justinianische Dynastie Justin I.,Justinian I.,Justin II.,Tiberios -

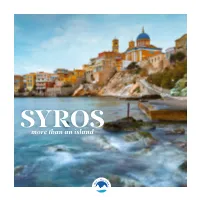

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Hierarchischer Thesaurus 2018

HIERARCHISCHER THESAURUS 2018 AUTOREN VON THESAURUS: KOΟRDINATION UND REDAKTION DR. IASONAS CHANDRINOS UND DAS HISTORIKER-TEAM DR. ANTONIS ANTONIOU DR. ANNA MARIA DROUMPOUKI KERASIA MALAGIORGI BB Begrenzter Begriff AB Ausgedehnter Begriff VB Verwandter Begriff SH Bereich Hinweis AB Organisationen on1_1 VF Verwenden für BB 5/42 Evzonen Regiment on1_2 VB Nationale und Soziale Befreiung 5/42 Syntagma Evzonon (5/42 SE), militärischer Arm der SH Widerstandsorganisation EKKA. BB Jung-Adler on1_1108 VB Vereinigte Panhellenische Jugendorganisation Nationale Befreiungsfront SH Kinderorganisation der Nationalen Befreiungsfront Griechenlands (EAM). BB Antifaschistische Organisation der Armee on1_2123 Geheimorganisation, welche 1942-43 von den exilierten, griechischen Streitkräften im Nahen Osten gebildet wurde. Wurde von KKE-Funktionären geleitet und hatte tausende von Soldaten, Matrosen und Offizieren vereint, welche sich im Konflikt mit den Königstreuen befanden. Zweigstellen von ihr waren die Antifaschistische Organisation der Marine (AON) und die Antifaschistische Organisation der Luftwaffe (AOA). Wurde im April 1944, nach SH der Unterdrückung der Bewegung durch die Briten, aufgelöst. BB Jagdkommando Schubert on1_1116 VB Schubert, Fritz Paramilitärische Einheit der Wehrmacht, welche 1943-1944 auf Kreta und in Makedonien aktiv war und unter dem Befehl des Oberfeldwebels der Geheimen Feldpolizei (GFP) Fritz Schubert stand. Diese unabhängige Einheit bestand aus etwa 100 freiwilligen Griechen und ihre offizielle deutsche Bezeichnung lautete "Jagdkommando -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

2011 Joint Conference

Joint ConferenceConference:: Hellenic Observatory,The British SchoolLondon at School Athens of & Economics & British School at Athens Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics Changing Conceptions of “Europe” in Modern Greece: Identities, Meanings, and Legitimation 28 & 29 January 2011 British School at Athens, Upper House, entrance from 52 Souedias, 10676, Athens PROGRAMME Friday, 28 th January 2011 9:00 Registration & Coffee 9:30 Welcome : Professor Catherine Morgan , Director, British School at Athens 9:45 Introduction : Imagining ‘Europe’. Professor Kevin Featherstone , LSE 10:15 Session One : Greece and Europe – Progress and Civilisation, 1890s-1920s. Sir Michael Llewellyn-Smith 11:15 Coffee Break 11:30 Session Two : Versions of Europe in the Greek literary imagination (1929- 1961). Professor Roderick Beaton , King’s College London 12:30 Lunch Break 13:30 Session Three : 'Europe', 'Turkey' and Greek self-identity: The antinomies of ‘mutual perceptions'. Professor Stefanos Pesmazoglou , Panteion University Athens 14:30 Coffee Break 14:45 Session Four : The European Union and the Political Economy of the Greek State. Professor Georgios Pagoulatos , Athens University of Economics & Business 15:45 Coffee Break 16:00 Session Five : Contesting Greek Exceptionalism: the political economy of the current crisis. Professor Euclid Tsakalotos , Athens University Of Economics & Business 17:00 Close 19:00 Lecture : British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens Former Prime Minister Costas Simitis on ‘European challenges in a time of crisis’ with a comment by Professor Kevin Featherstone 20:30 Reception 21:00 Private Dinner: British Ambassador’s Residence, 2 Loukianou, 10675, Athens - By Invitation Only - Saturday, 29 th January 2011 10:00 Session Six : Time and Modernity: Changing Greek Perceptions of Personal Identity in the Context of Europe. -

A Brief History of Greek Herpetology

Bonn zoological Bulletin Volume 57 Issue 2 pp. 329–345 Bonn, November 2010 A brief history of Greek herpetology Panayiotis Pafilis 1,2 1Section of Zoology and Marine Biology, Department of Biology, University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, Ilissia 157–84, Athens, Greece 2School of Natural Resources & Environment, Dana Building, 430 E. University, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI – 48109, USA; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract. The development of Herpetology in Greece is examined in this paper. After a brief look at the first reports on amphibians and reptiles from antiquity, a short presentation of their deep impact on classical Greek civilization but also on present day traditions is attempted. The main part of the study is dedicated to the presentation of the major herpetol- ogists that studied Greek herpetofauna during the last two centuries through a division into Schools according to researchers’ origin. Trends in herpetological research and changes in the anthropogeography of herpetologists are also discussed. Last- ly the future tasks of Greek herpetology are presented. Climate, geological history, geographic position and the long human presence in the area are responsible for shaping the particular features of Greek herpetofauna. Around 15% of the Greek herpetofauna comprises endemic species while 16% represent the only European populations in their range. THE STUDY OF REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS IN ANTIQUITY Greeks from quite early started to describe the natural en- Therein one could find citations to the Greek herpetofauna vironment. At the time biological sciences were consid- such as the Seriphian frogs or the tortoises of Arcadia. ered part of philosophical studies hence it was perfectly natural for a philosopher such as Democritus to contem- plate “on the Nature of Man” or to write books like the REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS IN GREEK “Causes concerned with Animals” (for a presentation of CULTURE Democritus’ work on nature see Guthrie 1996). -

N I~ ~L 'Ш Я .N OI ~V Wl Lo ~N I

.NI~~l'ШЯ .NOI~VWllO~NI .Edltorlal This issue of СА/В focuses on the fascist connection, in par in Latin America or the U.S. The Kameradenwerk-the Nazi ticular the U.S. role in helping hundreds, perhaps thousands, old Ьоу network-remained active over the years, vigorous of prominent Nazis avoid retribution ·at the end of World War enough to have planned and carried out · the 1980 coup in 11. The CIA (originally the OSS) and the U.S. military, along Bolivia, for example, and to have held high places in with the Vatican, were instrumental in exfiltrating war crimi Pinochet's govemment in Chile. And they are major figures in nals not just to Latin America, but to the United States as well. the intemational arms and drug trades as well-traffic which As the Reagan administration attempts to rewrite history, it the U.S. tries to Ыаmе on the socialist countries. is worthwhile to examine carefully the wartime and postwar Hundreds of Nazis have been set up in scientific institutions machinations of the extreme Right. The President goes to Bit in this country. Ironically, it now appears that Star W ars is burg claiming it is time to forgive and forget, when in reality merely an extension of the Nazis' wartime rocket research. he is merely cutting а crude political deal with the reactionary Much of the U.S. space program was designed Ьу them. When West German govemment for its approval of Star Wars Ьу giv the Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations leam ing his absolution to the SS. -

Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in the Aegean Island of Tsougriá, Northern Sporades, Greece

Biodiversity Journal , 2013, 4 (4): 553-556 Fi rst record of Hierophis gemonensis (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in the Aegean island of Tsougriá, Northern Sporades, Greece Mauro Grano¹ *, Cristina Cattaneo² & Augusto Cattaneo³ ¹ Via Valcenischia 24 – 00141 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] ² Via Eleonora d’Arborea 12 – 00162 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] ³ Via Cola di Rienzo 162 – 00192 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author ABSTRACT The presence of Hierophis gemonensis (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in Tsougriá, a small island of the Northern Sporades, Greece, is here recorded for the first time. KEY WORDS Aegean islands; Balkan whip snake; Hierophis gemonensis ; Northern Sporades; Tsougriá. Received 05.11.2013; accepted 02.12.2013; printed 30.12.2013 INTRODUCTION Psili: Clark, 1973, 1989; Kock, 1979. Tolon: Clark, 1973, 1989; Kock, 1979. The Balkan whip snake, Hierophis gemonensis Stavronissos, Dhokos, Trikkeri (archipelago of (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae), is Hydra): Clark, 1989. widespread along the coastal areas of Slovenia, Kythera: Boulenger, 1893; Kock, 1979. Croatia, Bosnia-Erzegovina, Montenegro, Albania Crete: Boettger, 1888; Sowig, 1985. and Greece (Vanni et al., 2011). The basic colour is Cretan islets silver gray to dark green with some spots only on Gramvoussa: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. one third of the body, tending to regular stripes on Gavdos: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. the tail. Melanistic specimens are also known Gianyssada: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. (Dimitropoulos, 1986; Schimmenti & Fabris, Dia: Raulin, 1869; Kock, 1979. 2000). The total length is usually less than 130 cm, Theodori: Wettstein, 1953. with males larger than females (Vanni et al., 2011).