Post-Socialist Urban Infrastructures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

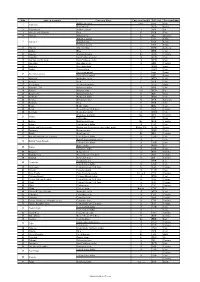

Valūtas Kods Valūtas Nosaukums Vienības Par EUR EUR Par Vienību

Valūtas kods Valūtas nosaukums Vienības par EUR EUR par vienību USD US Dollar 1,185395 0,843601 EUR Euro 1,000000 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,908506 1,100708 INR Indian Rupee 87,231666 0,011464 AUD Australian Dollar 1,674026 0,597362 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,553944 0,643524 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,606170 0,622599 CHF Swiss Franc 1,072154 0,932702 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,913417 0,203524 JPY Japanese Yen 124,400574 0,008039 Chinese Yuan CNY 7,890496 0,126735 Renminbi NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,791828 0,558089 THB Thai Baht 37,020943 0,027012 HUF Hungarian Forint 363,032464 0,002755 AED Emirati Dirham 4,353362 0,229708 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 9,186936 0,108850 MXN Mexican Peso 24,987903 0,040019 ZAR South African Rand 19,467073 0,051369 PHP Philippine Peso 57,599396 0,017361 SEK Swedish Krona 10,351009 0,096609 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 17356,035415 0,000058 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,445230 0,224960 BRL Brazilian Real 6,644766 0,150494 TRY Turkish Lira 9,286164 0,107687 KES Kenyan Shilling 128,913350 0,007757 KRW South Korean Won 1342,974259 0,000745 EGP Egyptian Pound 18,626384 0,053687 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1413,981158 0,000707 NOK Norwegian Krone 10,925023 0,091533 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,362319 2,759999 RUB Russian Ruble 91,339545 0,010948 DKK Danish Krone 7,442917 0,134356 PKR Pakistani Rupee 192,176964 0,005204 ILS Israeli Shekel 4,009399 0,249414 PLN Polish Zloty 4,576445 0,218510 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,314837 0,231758 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000618 1618,929841 OMR Omani Rial 0,455784 2,194020 COP Colombian Peso 4533,946955 0,000221 CLP Chilean Peso 931,726512 0,001073 -

Twelfth Session of the Speca Governing Council Infor

UNECE ESCAP United Nations Economic United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Europe Commission for Asia and the Pacific UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL PROGRAMME FOR THE ECONOMIES OF CENTRAL ASIA (SPECA) 2017 SPECA ECONOMIC FORUM “Innovation for the SDGs in the SPECA region” and TWELFTH SESSION OF THE SPECA GOVERNING COUNCIL (Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 5-6 December 2017) INFORMATION NOTICE I. INTRODUCTION This document provides some details regarding the 2017 SPECA Economic Forum “Innovation for the SDGs in the SPECA region” and the twelfth session of the SPECA Governing Council jointly organized by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific at the invitation of the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan and in close cooperation with the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of the Republic of Tajikistan. II. PARTICIPATION Government representatives of the United Nations member States, representatives of United Nations agencies and programmes, relevant international and regional organizations, international financial institutions, donors as well as representatives of the private sector and the academic community are invited to participate in the Economic Forum. Representatives of neighbouring countries, other countries interested in supporting the Programme, United Nations agencies and programmes, international and regional organizations, international financial institutions and donor agencies are invited to attend the twelfth session of the SPECA Governing Council as observers. III. VENUE These SPECA events will take place on 5-6 December 2017 in the conference room of the Hyatt Regency Dushanbe Hotel (address: Avenue Ismoili Somoni 26/1, Dushanbe). IV. ORGANIZATION Registration of participants will start at 09:00 on 5 December 2017. -

Baltic Region

ISSN 2079-8555 e-ISSN 2310-0524 BALTIC REGION 2019 Vol. 11 № 3 KALININGRAD Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University Press 2019 BALTIC Editorial council REGION Prof. Andrei P. Klemeshev, rector of the Immanuel Kant Baltic Fe de ral University, Russia ( Editor in Chief); Prof. Gennady M. Fedo rov, director of the Institute of Environmental Management, Terri to rial Development and Urban Construction, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal 2019 University, Russia (Deputy Chief Editor); Prof. Dr Joachim von Braun, director of the Center for Development Research (ZEF), Professor, Volume 11 University of Bonn, Germany; Prof. Irina M. Busygina , Department of № 3 Comparative Politics, Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University), Russia; Prof. Ale ksander G. Druzhinin, director of the North Caucasian Research Institute of Economic and Social Problems, Southern Federal University, Russia; Prof. Mikhail V. Ilyin, Kaliningrad : Prof. of the Department of Comparative Politics, Moscow State I. Kant Baltic Federal Institute of International Re lations (MGIMO University), Russia; University Press, 2019. 170 р. Dr Pertti Joenniemi, senior researcher, Karelian Institute, University of Eastern Finland, Fin land; Dr Nikolai V. Kaledin, head of the The journal Department of Regional Policy & Political Geography, Saint Petersburg was established in 2009 State University, Russia (cochair); Prof. Konstantin K. Khudolei, head of the De partment of European Studies, Faculty of International Frequency: Relations, Saint Petersburg State University, Russia; Dr Kari Liuhto, quarterly director of the PanEuropean Institute, Turku, Finland; Prof. Vladimir in the Russian and English A. Ko losov, head of the Laboratory for Geopolitical Studies, Institute languages per year of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences; Prof. -

Spartacist No. 41-42 Winter 1987-88

· , NUMBER 41-42 ENGLISH EDITION WINTER 1987-88 .ONE DOLLAR/75 PENCE ," \0, 70th Anniversary of Russian Revolution Return to the Road of Lenin and, Trotskyl PAGE 4 e___ __ _. ...,... • :~ Where Is Gorbachev's Russia Going? PAGE 20 TheP.oland,of LU)(,emburgvs.th'e PolalJdof Pilsudski ;... ~ ;- Me.moirs ofaRevoluti0l.1ary Je·wtsl1 Worker A Review .., .. PAGE 53 2 ---"---Ta bI e of Contents -'---"..........' ..::.....-- International Class-Struggle Defense , '. Soviet Play Explodes Stalin's Mo!?cow Trials Free Mordechai Vanunu! .................... 3 'Spectre of, Trotsky Hau'nts '- " , Gorbachev's' Russia ..... : .... : ........ : ..... 35 70th Anniversary of Russian Revolution Reprinted from Workers ,vanguard No, 430, Return'to the Road of 12 June 1987 ' lenin and Trotsky! ..... , ..................... 4 Leni~'s Testament, •.....• : ••••.•.. : ~ •••....•• : .1 •• 37' , Adapted from Workers Vanguard No, 440, The Last Wo~ds of, Adolf Joffe ................... 40 , 13 November 1987' 'j' .•. : Stalinist Reformers Look to the Right Opposition:, ' Advertisement: The Campaign to \ Bound Volumes of the Russian "Rehabilitate" Bukharin ...•.... ~ .... '..... ;. 41 , Bulletin of the'OpP-osition, 1929-1941 .... 19 , Excerpted from Workers Vanguard No. 220, 1 December 1978, with introduction by Spartacist 06'bRBneHMe: nonHoe M3AaHMe pyccKoro «EilOnneTeHR In Defense of Marshal Tukhachevsky ...,..45 , Onn03M4MM» 1929-1941 ................ .' .... ,". 19 Letter and reply reprinted from Workers Vanguard No'. 321, 14 January 1983' Where Is Gorbachev's Russia -

Currency Code Currency Name Units Per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282

Currency code Currency name Units per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282 EUR Euro 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,891731 INR Indian Rupee 76,833664 AUD Australian Dollar 1,596830 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,463998 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,519556 CHF Swiss Franc 1,097908 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,585569 JPY Japanese Yen 120,445338 CNY Chinese Yuan Renminbi 7,657364 NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,660507 THB Thai Baht 34,435083 HUF Hungarian Forint 325,394724 AED Emirati Dirham 4,092202 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 8,705685 MXN Mexican Peso 21,275509 ZAR South African Rand 15,449937 PHP Philippine Peso 56,970569 SEK Swedish Krona 10,508745 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 15576,638324 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,178559 BRL Brazilian Real 4,190947 TRY Turkish Lira 6,353929 KES Kenyan Shilling 115,893733 KRW South Korean Won 1311,898493 EGP Egyptian Pound 18,508337 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1326,662413 NOK Norwegian Krone 9,632916 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,339171 RUB Russian Ruble 70,335592 DKK Danish Krone 7,465851 PKR Pakistani Rupee 179,387706 ILS Israeli Shekel 3,926669 PLN Polish Zloty 4,255048 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,055988 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000784 OMR Omani Rial 0,428442 COP Colombian Peso 3560,158642 CLP Chilean Peso 770,643233 TWD Taiwan New Dollar 34,639236 ARS Argentine Peso 47,788112 CZK Czech Koruna 25,516024 VND Vietnamese Dong 25847,134851 MAD Moroccan Dirham 10,697013 JOD Jordanian Dinar 0,790026 BHD Bahraini Dinar 0,418970 XOF CFA Franc 655,957000 LKR Sri Lankan Rupee 196,347604 UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 28,564201 NGN Nigerian Naira 403,643263 TND Tunisian Dinar 3,212774 UGX Ugandan Shilling 4118,051290 -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Five Continents

eCONTI by N.L Vavilov Finally published in English, this book contains descriptions by Academician NI. Vavilov ofthe expeditions he made between 1916 and 1940 to jive continents, in search ofnew agricultural plants and conjil1nation ofhis theories on plant genetic divmity. Vavilov is ironic, mischievolls, perceptive, hilariolls and above all scholarly. This book is a readable testament to his tenacity and beliefin his work, in the foee ofthe greatest adversity. 11 This book is dedicated fa the memory of Nicolay Ivanovich Vavilov (1887-1943) on the IIOth anniversary of his birth 11 N.!. Vavilov Research Institure of Plant Industry • International Plant Genetic Resources Institute United States Agency for International Development • American Association for the Advancement of Science United States Depanment ofAgriculture • Agricultural Research Service • National Agricultural Library • THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF N/COLAY IVANOVICH VAVILOV (1887-1943) ON THE 11 Oth ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH • • FIVE CONTINENTS NICOLAY IVANOVICH VAVILOV Academy ofSciences, USSR Chemical Technological and Biological Sciences Editor-in-chief L.E. ROOIN Tramkzted ft-om the Russian by OORIS LOVE Edited by SEMYON REZNIK and PAUL STAPLETON 1997 • The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) is an autonomous international scientific organization operating under the aegis of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The international status of IPGRI is conferred under an Establishment Agreement signed by the Governments ofAustralia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, COSta Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritania. Morocco, Pa!cisran, Panama, Peru, Poland, Porrugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Sloval, Republic, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and the Ukraine. -

Turkey Visa Free List 2021 Visa Free Countries 2021

Turkey Visa Free List 2021 Visa Free Countries 2021 Republic of Turkey Visa restrictions 2021 - Applicable to citizens and passport holders traveling abroad Country Visa requirement Allowed stay Notes (excluding departure fees) Afghanistan Visa required[2] Albania Visa not required[3] 90 days Algeria Visa required[4] Because this country has no airport of its own, you need to arrive in Andorra Visa not required[5] 90 days France or Spain first and visas are required to enter into these countries. Angola Visa required[6] Antigua and Barbuda Visa not required[7] 180 days Argentina Visa not required[8] 90 days Armenia eVisa / Visa on arrival[9] 120 days Australia Visa required[10] May apply online (Online Visitor e600 visa).[11] Austria Visa required[12] ID card valid[15] If staying more than 15 days, visitors staying outside hotels must register Azerbaijan Visa not required[13][14] 90 days with local police. Bahamas Visa not required[16] 8 months Bahrain eVisa / Visa on arrival[17] 14 days May apply for eVisa. Bangladesh Visa on arrival[18] 30 days Barbados Visa not required[19] 6 months Belarus Visa not required[20] 30 days Belgium Visa required[21] Belize Visa not required[22] 90 days eVisa / Visa on arrival[23] Benin [24] 30 days / 8 days Must have an international vaccination certificate. Bhutan Visa required[25] Bolivia Visa not required[26] 90 days Bosnia and Herzegovina Visa not required[27] 90 days 90 days within any 6-month period 09/03/2021 1 Turkey Visa Free List 2021 Visa Free Countries 2021 Botswana Visa not required[28] 90 -

Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee ALL Albanian Lek HRK Croatian Kuna LT L Lithuanian Litas SLL Sierra Leonean Leone DZD Algerian Dinar CZK Czech Koruna MKD/FYR Macedonia Denar SGD Singapore Dollar AMD Armenian Dram DKK Danish Krone MOP Macau Pataca SBD Solomon Islands Dollar AOA Angola Kwanza DJF Djibouti Franc MGA Madagascar Ariary ZAR South African Rand AUD Australian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MWK Malawi Kwacha SSP South Sudanese Pound AWG Arubian Florin XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SRD Suriname Dollar AZN Azerbaijan Manat EGP Egyptian Pound MRU Mauritanian Olguiya SEK Swedish Krona BSD Bahamian Dollar EUR EMU Euro MUR Mauritius Rupee SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BHD Bahraini Dinar ERN Eritrea Nakfa MXN Mexican Peso CHF Swiss Franc BBD Barbados Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MDL Maldavian Lieu LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BYN Belarus Ruble FJ D Fiji Dollar MNT Mongolian Tugrik TWD Taiwan New Dollar BZD Belize Dollar GMD Gambian Dalasi MZN Mozambique Metical TJS Tajikistani Somoni BMD Bermudian Dollar GEL Georgian Larii MYR Malaysian Ringgit TZS Tanzanian Shilling BTN Bhutan Ngultram GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal MMK Burmese Kyat TOP Tongan Pa’anga BOB Bolivian Boliviano GNF Guinea Republic Franc NAD Namibian Dollar TTD Trinidad and Tobago Dollar BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GYD Guyana Dollar ANG Netherlands Antillean Guilder TRY Turkish Lira BWP Botswana Pula HTG Haitian Gourde NPR Nepal Rupee TMT Turkmenistani Manat BRL Brazilian Real HNL Honduran Lempira NZD New Zealand Dollar AED U.A.E. -

Local Currency Financing Treasury October 2014 Contents

Local Currency Financing Treasury October 2014 Contents • Rationale for Lending and Borrowing in Local Currency • Local Currency Portfolio • Local Currency Financing Platform • EBRD’s Role in Capital Markets Development Local Currency Financing Integral to the Bank’s Mission “To stimulate and encourage the development of capital markets” Agreement Establishing the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (Chapter 1, Article 2. Functions) Rationale for Lending in Local Currency Section 1 Section 3 Section 4 Section 2 Rationale for Lending and Local Currency Financing EBRD’s Role in Capital Markets Local Currency Portfolio Borrowing in Local Currency Platform Development By LENDING in local currency, the Bank is able to: • Improve the creditworthiness of projects which solely generate local currency income by avoiding FX risk • Direct short-term liquidity back into the real economy • Extend the maturity of local currency loans available in the market • Reinforce existing market indices, or create new, transparent ones • Stem unhedged currency mismatches on the balance sheets of both corporate and household sectors Rationale for Borrowing in Local Currency Section 1 Section 3 Section 4 Section 2 Rationale for Lending and Local Currency Financing EBRD’s Role in Capital Markets Local Currency Portfolio Borrowing in Local Currency Platform Development By BORROWING in local currency, the Bank is able to: • Offer an alternative triple-A benchmark to the government curve, which will increase the transparency of corporate pricing in the domestic market • Create an opportunity for credit diversification in domestic investors’ portfolios • For international investors local currency Eurobonds can provide a AAA conduit allowing the dissociation of currency and currency allocation risks. -

Monedas De Pago Aceptadas

MONEDAS DE PAGO ACEPTADAS AED: United Arab Emirates Dirham AFN: Afghan Afghani* ALL: Albanian Lek AMD: Armenian Dram ANG: Netherlands Antillean Gulden AOA: Angolan Kwanza* ARS: Argentine Peso* AUD: Australian Dollar AWG: Aruban Florin AZN: Azerbaijani Manat BAM: Bosnia & Herzegovina Convertible Mark BBD: Barbadian Dollar BDT: Bangladeshi Taka BGN: Bulgarian Lev BIF: Burundian Franc BMD: Bermudian Dollar BND: Brunei Dollar BOB: Bolivian Boliviano* BRL: Brazilian Real* BSD: Bahamian Dollar BWP: Botswana Pula BZD: Belize Dollar CAD: Canadian Dollar CDF: Congolese Franc CHF: Swiss Franc CLP: Chilean Peso* CNY: Chinese Renminbi Yuan COP: Colombian Peso* CRC: Costa Rican Colón* CVE: Cape Verdean Escudo* CZK: Czech Koruna* DJF: Djiboutian Franc* DKK: Danish Krone DOP: Dominican Peso DZD: Algerian Dinar EEK: Estonian Kroon* EGP: Egyptian Pound ETB: Ethiopian Birr EUR: Euro FJD: Fijian Dollar FKP: Falkland Islands Pound* GBP: British Pound GEL: Georgian Lari GIP: Gibraltar Pound GMD: Gambian Dalasi GNF: Guinean Franc* GTQ: Guatemalan Quetzal* GYD: Guyanese Dollar HKD: Hong Kong Dollar HNL: Honduran Lempira* HRK: Croatian Kuna HTG: Haitian Gourde HUF: Hungarian Forint* IDR: Indonesian Rupiah ILS: Israeli New Sheqel INR: Indian Rupee* ISK: Icelandic Króna JMD: Jamaican Dollar JPY: Japanese Yen KES: Kenyan Shilling KGS: Kyrgyzstani Som KHR: Cambodian Riel KMF: Comorian Franc KRW: South Korean Won KYD: Cayman Islands Dollar KZT: Kazakhstani Tenge LAK: Lao Kip* LBP: Lebanese Pound