Talking About Fonts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here I Raise My Ebenezer; Hither by Thy Help I’M Come; and I Hope, by Thy Good Pleasure, Safely to Arrive at Home

ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT WEEKEND 2021_commencement_program_v11a_draft.indd 1 4/30/2021 9:32:16 AM 2021_commencement_program_v11a_draft.indd 2 4/30/2021 9:32:16 AM ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT WEEKEND GREENVILLE UNIVERSITY Greenville, Illinois Commencement May 8, 2021 President Suzanne A. Davis Board of Trustees Robert W. Bastian Steven L. Ellsworth Hugo Perez Venessa A. Brown Valerie J. Gin, Treasurer B. Elliott Renfroe Tyler Campo Jerry A. Hood Dennis N. Spencer Howard Costley, Jr., Vice Chair Karen A. Longman Kathleen J. Turpin, Chair D. Keith Cowart K. Kendall Mathews Melissa A. Westover, Secretary Dan R. Denbo Douglas M. Newton Mark D. Whitlock Paul S. Donnell Stephen Olson Donald D. Wolf Emeriti Trustees Sandra M. Boileau Lloyd G. Ganton J. Richard Schien Patricia A. Burd Yoshio D. Gotoh Marjorie R. Smith Jay G. Burgess Duane E. Hood Rebecca E. Smith James W. Claussen Paul R. Killinger Kendell G. Stephens David G. Colgan Pearson L. Miller Barry J. Swanson Michael L. Coling Wayne E. Neeley Craig W. Tidball Robert E. Cranston Wesley F. Phillips R. Ian Van Norman Dennis L. Fenton Ernest R. Ross, Jr. 2021_commencement_program_v11a_draft.indd 3 4/30/2021 9:32:16 AM Saturday, May 8, 2021, 10:00 A.M. President Suzanne A. Davis, presiding PRELUDE Rebecca N. Koebbe PROCESSIONAL Rebecca N. Koebbe WELCOME Suzanne A. Davis NATIONAL ANTHEM The Star Spangled Banner Francis Scott Key INVOCATION Sidney R. Webster SCRIPTURE Ivan M. Estevez Ephesians 1:11 (TPT) HYMN Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing Traditional American Melody Text: Robert Robinson Tune: Nettleton Come, Thou fount of every blessing, Tune my heart to sing Thy grace; Streams of mercy, never ceasing, Call for songs of loudest praise. -

Cumberland Tech Ref.Book

Forms Printer 258x/259x Technical Reference DRAFT document - Monday, August 11, 2008 1:59 pm Please note that this is a DRAFT document. More information will be added and a final version will be released at a later date. August 2008 www.lexmark.com Lexmark and Lexmark with diamond design are trademarks of Lexmark International, Inc., registered in the United States and/or other countries. © 2008 Lexmark International, Inc. All rights reserved. 740 West New Circle Road Lexington, Kentucky 40550 Draft document Edition: August 2008 The following paragraph does not apply to any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC., PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer of express or implied warranties in certain transactions; therefore, this statement may not apply to you. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in later editions. Improvements or changes in the products or the programs described may be made at any time. Comments about this publication may be addressed to Lexmark International, Inc., Department F95/032-2, 740 West New Circle Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40550, U.S.A. In the United Kingdom and Eire, send to Lexmark International Ltd., Marketing and Services Department, Westhorpe House, Westhorpe, Marlow Bucks SL7 3RQ. Lexmark may use or distribute any of the information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

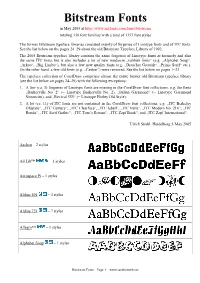

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at Totaling 350 Font Families with a Total of 1357 Font Styles

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/bitstream totaling 350 font families with a total of 1357 font styles The former Bitstream typeface libraries consisted mainly of forgeries of Linotype fonts and of ITC fonts. See the list below on the pages 24–29 about the old Bitstream Typeface Library of 1992. The 2005 Bitstream typeface library contains the same forgeries of Linotype fonts as formerly and also the same ITC fonts, but it also includes a lot of new mediocre „rubbish fonts“ (e.g. „Alphabet Soup“, „Arkeo“, „Big Limbo“), but also a few new quality fonts (e.g. „Drescher Grotesk“, „Prima Serif“ etc.). On the other hand, a few old fonts (e.g. „Caxton“) were removed. See the list below on pages 1–23. The typeface collection of CorelDraw comprises almost the entire former old Bitstream typeface library (see the list below on pages 24–29) with the following exceptions: 1. A few (ca. 3) forgeries of Linotype fonts are missing in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. the fonts „Baskerville No. 2“ (= Linotype Baskerville No. 2), „Italian Garamond“ (= Linotype Garamond Simoncini), and „Revival 555“ (= Linotype Horley Old Style). 2. A lot (ca. 11) of ITC fonts are not contained in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. „ITC Berkeley Oldstyle“, „ITC Century“, „ITC Clearface“, „ITC Isbell“, „ITC Italia“, „ITC Modern No. 216“, „ITC Ronda“, „ITC Serif Gothic“, „ITC Tom’s Roman“, „ITC Zapf Book“, and „ITC Zapf International“. Ulrich Stiehl, Heidelberg 3-May 2005 Aachen – 2 styles Ad Lib™ – 1 styles Aerospace Pi – 1 styles Aldine -

Type ID and History

History and Identification of Typefaces with your host Ted Ollier Bow and Arrow Press Anatomy of a Typeface: The pieces of letterforms apex cap line serif x line ear bowl x height counter baseline link loop Axgdecender line ascender dot terminal arm stem shoulder crossbar leg decender fkjntail Anatomy of a Typeface: Design decisions Stress: Berkeley vs Century Contrast: Stempel Garamond vs Bauer Bodoni oo dd AAxx Axis: Akzidenz Grotesk, Bembo, Stempel Garmond, Meridien, Stymie Q Q Q Q Q Typeface history: Blackletter Germanic, completely pen-based forms Hamburgerfonts Alte Schwabacher c1990 Monotype Corporation Hamburgerfonts Engraver’s Old English (Textur) 1906 Morris Fuller Benton Hamburgerfonts Fette Fraktur 1850 Johan Christian Bauer Hamburgerfonts San Marco (Rotunda) 1994 Karlgeorg Hoefer, Alexei Chekulayev Typeface history: Humanist Low contrast, left axis, “penned” serifs, slanted “e”, small x-height Hamburgerfonts Berkeley Old Style 1915 Frederic Goudy Hamburgerfonts Centaur 1914 Bruce Rogers after Nicolas Jenson 1469 Hamburgerfonts Stempel Schneidler 1936 F.H.Ernst Schneidler Hamburgerfonts Adobe Jenson 1996 Robert Slimbach after Nicolas Jenson 1470 Typeface history: Old Style Medium contrast, more vertical axis, fewer “pen” flourishes Hamburgerfonts Stempel Garamond 1928 Stempel Type Foundry after Claude Garamond 1592 Hamburgerfonts Caslon 1990 Carol Twombley after William Caslon 1722 Hamburgerfonts Bembo 1929 Stanley Morison after Francesco Griffo 1495 Hamburgerfonts Janson 1955 Hermann Zapf after Miklós Tótfalusi Kis 1680 Typeface -

CSS Font Stacks by Classification

CSS font stacks by classification Written by Frode Helland When Johann Gutenberg printed his famous Bible more than 600 years ago, the only typeface available was his own. Since the invention of moveable lead type, throughout most of the 20th century graphic designers and printers have been limited to one – or perhaps only a handful of typefaces – due to costs and availability. Since the birth of desktop publishing and the introduction of the worlds firstWYSIWYG layout program, MacPublisher (1985), the number of typefaces available – literary at our fingertips – has grown exponen- tially. Still, well into the 21st century, web designers find them selves limited to only a handful. Web browsers depend on the users own font files to display text, and since most people don’t have any reason to purchase a typeface, we’re stuck with a selected few. This issue force web designers to rethink their approach: letting go of control, letting the end user resize, restyle, and as the dynamic web evolves, rewrite and perhaps also one day rearrange text and data. As a graphic designer usually working with static printed items, CSS font stacks is very unfamiliar: A list of typefaces were one take over were the previous failed, in- stead of that single specified Stempel Garamond 9/12 pt. that reads so well on matte stock. Am I fighting the evolution? I don’t think so. Some design principles are universal, independent of me- dium. I believe good typography is one of them. The technology that will let us use typefaces online the same way we use them in print is on it’s way, although moving at slow speed. -

Adobe Font Folio Opentype Edition 2003

Adobe Font Folio OpenType Edition 2003 The Adobe Folio 9.0 containing PostScript Type 1 fonts was replaced in 2003 by the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition ("Adobe Folio 10") containing 486 OpenType font families totaling 2209 font styles (regular, bold, italic, etc.). Adobe no longer sells PostScript Type 1 fonts and now sells OpenType fonts. OpenType fonts permit of encrypting and embedding hidden private buyer data (postal address, email address, bank account number, credit card number etc.). Embedding of your private data is now also customary with old PS Type 1 fonts, but here you can detect more easily your hidden private data. For an example of embedded private data see http://www.sanskritweb.net/forgers/lino17.pdf showing both encrypted and unencrypted private data. If you are connected to the internet, it is easy for online shops to spy out your private data by reading the fonts installed on your computer. In this way, Adobe and other online shops also obtain email addresses for spamming purposes. Therefore it is recommended to avoid buying fonts from Adobe, Linotype, Monotype etc., if you use a computer that is connected to the internet. See also Prof. Luc Devroye's notes on Adobe Store Security Breach spam emails at this site http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/legal.html Note 1: 80% of the fonts contained in the "Adobe" FontFolio CD are non-Adobe fonts by ITC, Linotype, and others. Note 2: Most of these "Adobe" fonts do not permit of "editing embedding" so that these fonts are practically useless. Despite these serious disadvantages, the Adobe Folio OpenType Edition retails presently (March 2005) at US$8,999.00. -

Serif Fonts Vol 2

Name Chaparral Pro Basic Latin ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < = > ? @ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z [ \ ] ^ _ ` a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z { | } ~ 24 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 18 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 12 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 10 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 8 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog Name Chaparral Pro Bold Basic Latin ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < = > ? @ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z [ \ ] ^ _ ` a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z { | } ~ 24 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 18 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 12 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 10 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 8 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog Name Chaparral Pro Bold Italic Basic Latin ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < = > ? @ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z [ \ ] ^ _ ` a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z { | } ~ 24 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 18 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 12 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 10 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog 8 Te quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog Name Chaparral Pro Italic Basic Latin ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * + , - . -

Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva

Type design for typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA in Typeface Design Department of Typography & Graphic Communication University of Reading, United Kingdom September 2015 The word utopia is the most convenient way to sell off what one has not the will, ability, or courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until one begin to work on it. Only then it becomes a goal, which is something infinitely bigger.1 -- Adriano Olivetti. 1 Original text: ‘Il termine utopia è la maniera più comoda per liquidare quello che non si ha voglia, capacità, o coraggio di fare. Un sogno sembra un sogno fino a quando non si comincia da qualche parte, solo allora diventa un proposito, cio è qualcosa di infinitamente più grande.’ Source: fondazioneadrianolivetti.it. -- Abstract The history of the typewriter has been covered by writers and researchers. However, the interest shown in the origin of the machine has not revealed a further interest in one of the true reasons of its existence, the printed letters. The following pages try to bring some light on this part of the history of type design, typewriter typefaces. The research focused on a particular company, Olivetti, one of the most important typewriter manufacturers. The first two sections describe the context for the main topic. These introductory pages explain briefly the history of the typewriter and highlight the particular facts that led Olivetti on its way to success. The next section, ‘Typewriters and text composition’, creates a link between the historical background and the machine. -

The Monotype Library Opentype Edition

en FR De eS intRoDuction intRoDuction einFühRung pReSentación Welcome to The Monotype Library, OpenType Edition; a renowned Bienvenue à la Typothèque Monotype, Édition OpenType; une collection Willkommen bei Monotype, einem renommierten Hersteller klassischer Bienvenido a la biblioteca Monotype, la famosa colección de fuentes collection of classic and contemporary professional fonts. renommée de polices professionnelles classiques et contemporaines. und zeitgenössischer professioneller Fonts, die jetzt auch im OpenType- profesionales clásicas y contemporáneas, ahora también en formato Format erhältlich sind. OpenType. The Monotype Library, OpenType Edition, offers a uniquely versatile La Typothèque Monotype, Édition OpenType propose une collection range of fonts to suit every purpose. New additions include eye- extrêmement souple de polices pour chaque occasion. Parmi les Die Monotype Bibliothek, die OpenType Ausgabe bietet eine Esta primera edición de la biblioteca Monotype en formato OpenType catching display faces such as Smart Sans, workhorse texts such as nouvelles polices, citons des polices attrayantes destinées aux affichages einzigartig vielseitige Sammlung von Fonts für jeden Einsatz. Neben ofrece un gran repertorio de fuentes cuya incomparable versatilidad Bembo Book, Mentor and Mosquito Formal plus cutting edge Neo comme Smart Sans, des caractères très lisibles comme Bembo Book, den klassischen Schriften werden auch neue Schriftentwicklungen wie permite cubrir todas las necesidades. Entre las nuevas adiciones destacan Sans & Neo Tech. In this catalogue, each typeface is referenced by Mentor et Mosquito Formal, et des polices de pointe comme Neo die Displayschrift Smart Sans, Brotschriften wie Bembo Book, Mentor llamativos caracteres decorativos como Smart Sans, textos básicos classification to help you find the font most suitable for your project. -

Design One Project Three Introduced March 21. Due April 11. Typeface

Design One Project Three Introduced March 21. Due April 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used or the evolving fashion of design. Type designers often have imagery in mind while they are designing faces. Eurostile, designed by Aldo Novarese in 1962, was inpsired by images of the 60s Italian streetcar windows and televisions. An analogy is a similarity in some respect between thngs that are otherwise dissimilar. Type is not a picture but the letter o of Eurostile shares a strong visual relationship with the window of a streetcar. And more importantly, it’s design reflects the modernism of the 1960s. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer.