Oboe Concertos of the Classical Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

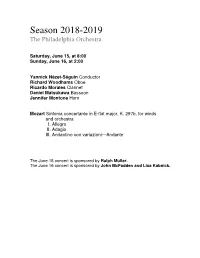

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Art Or Craft? – Significance of the Sociological Background in the Artistic Development of the Harmoniemusik

MUSICOLOGICA BRUNENSIA 47, 2012, 1 MIKOŁAJ RYKOWSKI ART OR CRAFT? – SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SOCIOLOGICAL BACKGROUND IN THE ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE HARMONIEMUSIK Harmoniemusik phenomenon has emerged in the most important 18th and 19th century domains of the musical life. It were aristocratic court, church circle and military service where these ensembles containing usually 2 cl., 2 ob., 2 cr., 2 bs. where active. Geographically these musical practise was spread out among many countries, but their so called ‘homeland’ was Holy Roman Empire territory (altough Moravian emigrants applied this music to Bethlehem parish in North America). Stylistically, existing repertoire embodies wide range of Wind Harmo- ny pieces where often in one musical centre it possible to notice that at particular period of time performed simple, garden-like, background music and artistically significant examples of the concert music. A matter of whether Harmoniemusik presents more art or craft is is concerned more to provoke a discussion about its multicontextual functioning rather than expecting white-or-black answers. It is a very important origin of the entire development that its musical condition depended almost fully on sociological background. Artistic judgment of these music should be provided regarding the fact that Wind Harmony came into appearance in various sociological contexts. Moreover, a certain role in sociological sphere required usage of adequate formal devices such as march-like opening movement for army band or dance music as characteristic for music played in aristocratic chambers. It is interesting to ob- serve in which way all these environments influenced the complexity and content of Harmoniemusik repertoire. The 18th century patronage of the army, court and church and its influence ex- erted over the artistic picture of wind ensembles appeared with different intensity. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Download Booklet

Classics Contemporaries of Mozart Collection COMPACT DISC ONE Franz Krommer (1759–1831) Symphony in D major, Op. 40* 28:03 1 I Adagio – Allegro vivace 9:27 2 II Adagio 7:23 3 III Allegretto 4:46 4 IV Allegro 6:22 Symphony in C minor, Op. 102* 29:26 5 I Largo – Allegro vivace 5:28 6 II Adagio 7:10 7 III Allegretto 7:03 8 IV Allegro 6:32 TT 57:38 COMPACT DISC TWO Carl Philipp Stamitz (1745–1801) Symphony in F major, Op. 24 No. 3 (F 5) 14:47 1 I Grave – Allegro assai 6:16 2 II Andante moderato – 4:05 3 III Allegretto/Allegro assai 4:23 Matthias Bamert 3 Symphony in G major, Op. 68 (B 156) 24:19 Symphony in C major, Op. 13/16 No. 5 (C 5) 16:33 5 I Allegro vivace assai 7:02 4 I Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 6 II Adagio 7:24 5 II Andante grazioso 6:07 7 III Menuetto e Trio 3:43 6 III Allegro 4:31 8 IV Rondo. Allegro 6:03 Symphony in G major, Op. 13/16 No. 4 (G 5) 13:35 Symphony in D minor (B 147) 22:45 7 I Presto 4:16 9 I Maestoso – Allegro con spirito quasi presto 8:21 8 II Andantino 5:15 10 II Adagio 4:40 9 III Prestissimo 3:58 11 III Menuetto e Trio. Allegretto 5:21 12 IV Rondo. Allegro 4:18 Symphony in D major ‘La Chasse’ (D 10) 16:19 TT 70:27 10 I Grave – Allegro 4:05 11 II Andante 6:04 12 III Allegro moderato – Presto 6:04 COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 61:35 Leopold Kozeluch (1747 –1818) 18:08 COMPACT DISC THREE Symphony in D major 1 I Adagio – Allegro 5:13 Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757 – 1831) 2 II Poco adagio 5:07 3 III Menuetto e Trio. -

Oboe Trios: an Annotated Bibliography

Oboe Trios: An Annotated Bibliography by Melissa Sassaman A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Martin Schuring, Chair Elizabeth Buck Amy Holbrook Gary Hill ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2014 ABSTRACT This project is a practical annotated bibliography of original works for oboe trio with the specific instrumentation of two oboes and English horn. Presenting descriptions of 116 readily available oboe trios, this project is intended to promote awareness, accessibility, and performance of compositions within this genre. The annotated bibliography focuses exclusively on original, published works for two oboes and English horn. Unpublished works, arrangements, works that are out of print and not available through interlibrary loan, or works that feature slightly altered instrumentation are not included. Entries in this annotated bibliography are listed alphabetically by the last name of the composer. Each entry includes the dates of the composer and a brief biography, followed by the title of the work, composition date, commission, and dedication of the piece. Also included are the names of publishers, the length of the entire piece in minutes and seconds, and an incipit of the first one to eight measures for each movement of the work. In addition to providing a comprehensive and detailed bibliography of oboe trios, this document traces the history of the oboe trio and includes biographical sketches of each composer cited, allowing readers to place the genre of oboe trios and each individual composition into its historical context. Four appendices at the end include a list of trios arranged alphabetically by composer’s last name, chronologically by the date of composition, and by country of origin and a list of publications of Ludwig van Beethoven's oboe trios from the 1940s and earlier. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Downloaded From

BÄRENREITER URTEXT offering the best CZECHMUSIC of Czech music BÄRENREITER URTEXT is a seal of quality assigned only to scholarly-critical editions. It guarantees that the musical text represents the current state of research, prepared in accordance with clearly defined editorial guidelines. Bärenreiter Urtext: the last word in authentic text — the musicians’ choice. Your Music Dealer SPA 314 SPA SALES CATALOGUE 2021 /2022 Bärenreiter Praha • Praha Bärenreiter Bärenreiter Praha | www.baerenreiter.cz | [email protected] | www.baerenreiter.com BÄRENREITER URTEXT Other Bärenreiter Catalogues THE MUSICIAN ' S CHOICE Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – The Programme 2019/2020 Das Programm 2018/2019 SPA 480 (Eng) SPA 478 (Ger) Bärenreiter's bestsellers for The most comprehensive piano, organ, strings, winds, catalogue for all solo chamber ensembles, and solo instruments, chamber music voice. It also lists study and and solo voice. Vocal scores orchestral scores, facsimiles and study scores are also and reprints, as well as books included. on music. Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter Music for Piano 2019/2020 Music for Organ Music for Organ 2014/2015 SPA 233 (Eng) 2014/2015 SPA 238 (Eng) Bärenreiter's complete Urtext Bärenreiter's Urtext programme for piano as well programme for organ as well as all educational titles and as collections and series. collections for solo and piano You will also find jazz works, four hands. Chamber music transcriptions, works for with piano is also listed. Your Music Dealer: organ and voice, as well as a selection of contemporary music. Bärenreiter-Verlag · 34111 Kassel · Germany · www.baerenreiter.com · SPA 238 MARTINŮ B Ä R E N R E I T E R U R T E X T Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – Music for Strings 2018/2019 Choral Music 2018/2019 Nonet č. -

Oboe Concertos

OBOE CONCERTOS LINER NOTES CD1-3 desire to provide the first recording of Vivaldi’s complete oboe Vivaldi: Oboe Concertos works. All things considered, even the concertos whose It is more than likely that Vivaldi’s earliest concertos for wind authenticity cannot be entirely ascertained reveal Vivaldi’s instruments were those he composed for the oboe. The Pietà remarkable popularity throughout Europe during the early years documents reveal a specific interest on his part for the of the 1700s, from Venice to Sweden, including Germany, instrument, mentioning the names of a succession of master Holland and England. If a contemporary publisher or composer oboists: Ignazio Rion, Ludwig Erdmann and Ignazio Sieber, as used the composer’s name in vain, perhaps attempting to well as Onofrio Penati, who had previously been a member of emulate his style, clearly he did so in the hope of improving his the San Marco orchestra. However, it was probably not one of chances of success, since Vivaldi was one of the most famous these musicians who inspired Vivaldi to write for the oboe, but and widely admired composers of his time. Indeed, in this sense instead the German soloist Johann Christian Richter, who was in imitation bears witness to the eminence of the original. Venice along with his colleagues Pisandel and Zelenka in 1716- Various problems regarding interpretation of text came to 1717, in the entourage of Prince Frederick Augustus of Saxony. the fore during the preparation of the manuscripts’ critical As C. Fertonani has suggested, Vivaldi probably dedicated the edition, with one possible source of ambiguity being Vivaldi’s Concerto RV455 ‘Saxony’ and the Sonata RV53 to Richter, who use of the expression da capo at the end of a movement (which may well have been the designated oboist for the Concerto was used so as to save him having to write out the previous RV447 as well, since this work also called for remarkable tutti’s parts in full). -

Solo Oboe, English Horn with Band

A Nieweg Chart Solo Oboe or Solo English Horn with Band or Wind Ensemble 95 editions April 2017 The 2017 Chart is an update of the 2010 Chart. It is not a complete list of all available works for Oboe or EH and band. Works with prices listed are for sale from any music dealer. Prices current as of 2010. Look at the publisher’s website for the current prices. Works marked rental must be hired directly from the publisher listed. Sample Band Instrumentation code: 3fl[1.2.3/pic] 2ob 7cl[Eb.1.2.3.acl.bcl.cbcl] 3bn[1.2.cbn] 4sax[a.a.t.b] — 4hn 3tp 3tbn euph tuba double bass — tmp+3perc — hp, pf, cel This listing gives the number of parts used in the composition, not the number of players. ------------------ Abbado, Marcello (b. Milan, 1926; ) Concerto in C minor (complete) Arranger / Editor: Trans. Charles T. Yeago Instrumentation: Oboe solo and band Pub: BAS Publishing. SOS-217 http://www.baspublishing.com ------------------ ALBINONI, Tommaso (1674-1745) Concerto in F for TWO Oboes and Band Adapted: Paul R. Brink Grade Level: Medium Pub: Bas Publishing Co.; Score and band set SOS-226 -$65.00 | 2 oboes and piano ENS-708. $10.00 ------------------ ARENZ, Heinz (b. 1924) German wind director, administrator, and composer Concertino fur Solo Oboe und Blasorchester Dur: 7'39" Grade Level: solo 6, band 5 Pub: HeBu Music Publishing; Band score and set 113.00 € Oboe and Piano 11.00 € ------------------ ATEHORTUA, Blas Emilio (b. Medellin, Columbia, 3 October 1933) Concerto for Oboe and Wind Symphony Orchestra Instrumentation listed <http://www.edition-peters.com/pdf/Albinoni-Grieg.pdf> Dur: 15' Pub: C. -

Concertos for Oboe and Oboe D'amore

J.S. Bach Concertos for Oboe and Oboe d’amore Gonzalo X. Ruiz Portland Baroque Orchestra Monica Huggett J.S. Bach (1685-1750) Concertos for Oboe and Oboe d’amore Gonzalo X. Ruiz, baroque oboes Portland Baroque Orchestra Concerto for oboe in G minor, BWV 1056R Concerto for oboe d’amore in A major, BWV 1055R Reconstruction of BWV 1056, Concerto in F minor for Harpsichord Reconstruction of BWV 1055, Concerto in A major for Harpsichord 1 I. [Moderato] 3:10 10 I. [Allegro] 3:56 2 II. Largo 2:25 11 II. Larghetto 4:39 3 III. Presto 3:13 12 III. Allegro ma non tanto 4:08 Concerto for oboe in F major, BWV 1053R Concerto for violin and oboe in C minor, BWV 1060R Reconstruction of BWV 1053, Concerto in E major for Harpsichord Reconstruction of BWV 1060, Concerto in C minor for Two Harpsichords 4 I. [Allegro] 7:05 Monica Huggett, violin soloist 5 II. Siciliano 4:56 13 I. Allegro 4:30 6 III. Allegro 5:46 14 II. Adagio 4:30 15 III. Allegro 3:27 Concerto for oboe in D minor, BWV 1059R Reconstruction based on a concerto fragment and Cantatas 35 and 156 16 Aria from Cantata 51: “Höchster, mache deine Güte” 4:56 7 I. Allegro 5:12 Transcribed by Gonzalo X. Ruiz 8 II. Adagio 2:26 9 III. Presto 3:02 Total Time 67:21 Performed on Period Instruments 2 Gonzalo X. Ruiz, baroque oboes Born in La Plata, Argentina, Gonzalo X. Ruiz is one of the world’s most critically acclaimed baroque oboists. -

Vorwort Zu PB 5308

PB 5308 Vorwort.qxp 16.06.2009 15:35 Seite 1 Vorwort 1. Zur Entstehungsgeschichte (3) Das Aufführungsmaterial, das für den Oboisten „vom fürst Ester- Das vorliegende Konzert KV 314 ist in zwei Fassungen überliefert, hazi“ angefertigt werden sollte. Leider hat sich keine dieser drei Quel- nämlich als Oboenkonzert in C-dur und als Flötenkonzert in D-dur. Die len erhalten. Oboenfassung wird in der Mozartschen Familienkorrespondenz mehr- Überhaupt galt Mozarts Oboenkonzert lange Zeit als verschollen. Erst fach erwähnt. Diese Informationen aus erster Hand geben wichtige 1920 wurde ein historisches Stimmenmaterial vom Oboenkonzert (Ob- Auskunft über Entstehungsgeschichte, historische Aufführungen und S-s) im Archiv des Salzburger Mozarteums durch Bernhard Paumgart- Quellen des Oboenkonzerts – mehr als über jedes andere Bläserkon- ner wiederentdeckt. Es ist heute die einzige historische Quelle für das zert von Mozart. Oboenkonzert. Dieses Stimmenmaterial ist jedoch nicht mit den zu Mozarts Lebzeiten angefertigten Stimmenmaterialien identisch, son- 1.1. Oboenkonzert dern entstand, dem Wasserzeichen nach zu urteilen, vermutlich erst nach Mozarts Tod und stammt aus der Schreibstube von Johann Traeg Das Oboenkonzert wird erstmals in einem Brief von Leopold Mozart in Wien.10 1971 tauchte außerdem in Privatbesitz eine neuntaktige erwähnt. Er schreibt am 15. Oktober 1777 an seinen auf der Reise autographe Skizze in C-dur auf.11 Sie bestätigt sowohl Authentizität nach Mannheim befindlichen Sohn: „Nun liegt dir aber immer mehr als auch Priorität der Oboenfassung. daran etwas für den Fürst Taxis zu haben. – – und wäre das Oboe= Concert herausgeschrieben, so würde es dir in Wallerstein, wegen 1.2. Flötenkonzert dem [Oboisten] Perwein etwas eintragen.“1 Für die darauf folgende Die Flötenfassung ist der Wissenschaft länger bekannt als die Oboen- Zeit lässt sich ein Treffen zwischen Mozart und Johann Marcus Berwein, fassung.