RICE UNIVERSITY an Oboe and Oboe D'amore Concerto from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

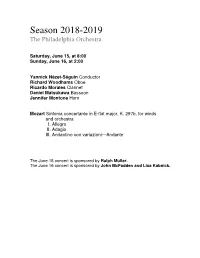

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Saturday Playlist

October 26, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 008 in G, "Evening" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 423 098 028942309821 00:24 Buy Now! Scarlatti, D. Sonata in A, Kirkpatrick 212 Murray Perahia Sony 63380 07464633802 00:28 Buy Now! Grieg Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 Philharmonia Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 01:00 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ Cinderella EMI 49155 077774915526 Fields/Marriner 01:09 Buy Now! Parry Elegy for Brahms London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 49022 07777490222 01:20 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. 1 in B flat, Op. 18 Stern/Lin/Laredo/Tree/Ma/Robinson Sony Classical 45820 07464458202 02:00 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Alicia de Larrocha RCA Red Seal 60453 090266045327 Lento assai ~ String Quartet in F, Op. 135 (arr. 02:15 Buy Now! Beethoven Royal Philharmonic/Rosekrans Telarc 80562 089408056222 for string orchestra) 02:27 Buy Now! Gade Symphony No. 7 in F, Op. 45 Stockholm Sinfonietta/Jarvi BIS 355 7318590003558 03:00 Buy Now! Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Zoeller/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan EMI 65914 724356591424 03:11 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Cello Sonata No. 1 in B flat, Op. 45 Rosen/Artymiw Bridge 9501 090404950124 03:37 Buy Now! Offenbach Offenbachiana Monte Carlo Philharmonic/Rosenthal Naxos 8.554005 N/A 04:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Havanaise, Op. -

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

Symphony 04.22.14

College of Fine Arts presents the UNLV Symphony Orchestra Taras Krysa, music director and conductor Micah Holt, trumpet Erin Vander Wyst, clarinet Jeremy Russo, cello PROGRAM Oskar Böhme Concerto in F Minor (1870–1938) Allegro Moderato Adagio religioso… Allegretto Rondo (Allegro scherzando) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Rondo: Allegro Edward Elgar Cello Concerto, Op. 85 (1857–1934) Adagio Lento Adagio Allegro Tuesday, April 22, 2014 7:30 p.m. Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall Performing Arts Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES The Concerto in F minor Composed 1899 Instrumentation solo trumpet, flute, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, four horns, trumpet, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Oskar Bohme was a trumpet player and composer who began his career in Germany during the late 1800’s. After playing in small orchestras around Germany he moved to St. Petersburg to become a cornetist for the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra. Bohme composed and published is Trumpet Concerto in E Minor in 1899 while living in St. Petersburg. History caught up with Oskar Bohme in 1934 when he was exiled to Orenburg during Stalin’s Great Terror. It is known that Bohme taught at a music school in the Ural Mountain region for a time, however, the exact time and circumstances of Bohme’s death are unknown. Bohme’s Concerto in F Minor is distinguished because it is the only known concerto written for trumpet during the Romantic period. The concerto was originally written in the key of E minor and played on an A trumpet. -

Handel' S Organ Concerto S Reconsidered

Handel' s Organ ConcertoConcertos s Reconsidered By NIELS KARL NIELSEN Due to the solid foundatiansfoundations provided by the research carried out by Chrysan der, W. Dean, O. E. Deutsch, J. P. Larsen, W. C. Smith and others the study of Randel'sHandel's works has been rendered much easier to-day than it was a mere twenty years ago; this, however, does not mean that all the problems have been solved. On the contrary, many still await exhaustive treatment. Whereas a vast number of books have been written ab out Randel'sHandel's vocal compositions, and the Oratorios in particular, a detailed study of his Organ Concertos, based on the autograph scores and other contemporary sources has not yet been made. Ehrlinger's dissertation 1 contains many valuable observa tions; nevertheless its importance is reduced considerably by the faetfact that he did not incorporate the original sources in his research. Accordingly, in the present study I intend to remedy this gap in our knowl edge of RandelHandel and his work, by discussing problems such as-date of composi tion-sources-original versions-style afof performance, and last but not least, the inevitable question of Randel'sHandel's borrowings. Some of these problems have of course been dealt with before, but I still find it worthwhile to try and collate as much information as possibiepossible about these aspects of Randel'sHandel's wark.work. RandelHandel embarked upon his concertos for organ and orchestra in dose con nection with his efforts to introduce the oratorio as a parallel to the produetionproduction of operas which had dominated his work in London up to the beginning of the 1730's. -

AN ANALYSIS of “SEVEN LAST WORDS from the CROSS” (1993) by JAMES MACMILLAN by HERNHO PARK DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial

AN ANALYSIS OF “SEVEN LAST WORDS FROM THE CROSS” (1993) BY JAMES MACMILLAN BY HERNHO PARK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Choral Music in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Barrington Coleman, Chair Professor Carlos Carrillo, Director of Research Professor Michael Silvers Professor Fred Stoltzfus ABSTRACT James MacMillan is one of the most well-known and successful living composers as well as an internationally active conductor. His musical language is influenced by his Scottish heritage, the Catholic faith, and traditional Celtic folk music, blended with Scandinavian and European composers including Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), Alfred Schnittke (1943-1998), and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971). His cantata for choir and strings Seven Last Words from the Cross, was commissioned by BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) television, composed in 1993, and premiered in 1994 by Cappella Nova and the BT (British Telecom) Scottish Ensemble. While this piece is widely admired as one of his best achievements by choral conductors and choirs, it is rarely performed, perhaps due to its high level of difficulty for both the string players and singers. The purpose of this dissertation is to present an analysis of the Seven Last Words from the Cross by James MacMillan aimed to benefit choral conductors rather than audiences. Very little has been written about MacMillan's choral works. My hope is to establish a foundation on which future scholars may expand and explore other choral works by MacMillan. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Solo and Ensemble Concert Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium July 17, 1967 8:00 P.M

SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT MAE ZENKE ORVIS AUDITORIUM JULY 17, 1967 8:00 P.M. SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT Monday, July 17 Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium 8:00 P.M. Program Ernst Krenek Piano Sonata No.3 (1943) Peter Coraggio, piano Allegretto piacevole Theme, Canons and Variations: Andantino Scherzo: Vivace rna non troppo Adagio First Performance in Hawaii Neil McKay Sonata for French Horn and Willard Culley, French horn Piano (1962) Marion McKay, piano Fanfare: Allegro Andante Allegro First Performance in Hawaii Chou Wen-chung Yu Ko (1965) Chou Wen-chung, conductor First Performance in Hawaii John Merrill, violin Jean Harling, alto flute James Ostryniec, English horn Henry Miyamura, bass clarinet Roy Miyahira, trombone Samuel Aranio, bass trombone Zoe Merrill, piano Lois Russell, percussion Edward Asmus, percussion INTERMISSION JOSe Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion and Men's Voices First Performance in Hawaii Jose Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion Charles Higgins and Men's Voices William Feltz First Performance in Hawaii Brian Roberts voices San Do Alfredo lagaso John Van der Slice l Takefusa Sasamori tubes Bach Mai Huong Ta buzzers ~ Ruth Pfeiffer jaw's harps Earlene Tom Thi Hanh le William Steinohrt Marcia Chang zithers Michael Houser } Auguste Broadmeyer Nancy Waller scrapers Hailuen } Program Notes The Piano Sonata NO.3 was written in 1943. The first movement is patterned after the classical model: expo sition (with first, second, and concluding themes), development, recapitulation, and coda. However, in each of these sections the thematic material is represented in musical configurations derived from one of the four basic forms of the twelve-tone row: original, inversion, retrograde, and retrograde inversion. -

Magnus Lindberg 1

21ST CENTURY MUSIC FEBRUARY 2010 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2010 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal.