Concertos for Oboe and Oboe D'amore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

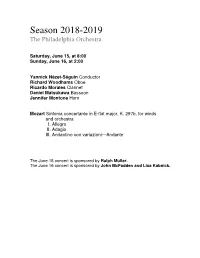

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 88

BOSTON SYMPHONY v^Xvv^JTa Jlj l3 X JlVjl FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 PAIGE OBRION RUSSELL Insurance Since 1876 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ROBERT H.GARDINER Vice-President EDWARD M. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

14 January 2011 Page 1 of 9

Radio 3 Listings for 8 – 14 January 2011 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 08 JANUARY 2011 05:37AM virtuosity, but it's quite possible he wrote this concerto to play Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) himself. One early soloist commented that the middle SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00wx4v1) Alma Dei creatoris (K.277) movement was 'too clever by half', but it's the finale that's The Genius of Mozart, presented by John Shea Ursula Reinhardt-Kiss (soprano); Annelies Burmeister (mezzo); catches most attention today, as it suddenly lurches into the Eberhard Büchner (tenor); Leipzig Radio Chorus & Symphony 'Turkish' (or more accurately Hungarian-inspired) style - and 01:01AM Orchestra), Herbert Kegel (conductor) the nickname has stuck. Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) Thamos, König in Ägypten (K.345) 05:43AM Conductor Garry Walker is no stranger to Mozart, last season Monteverdi Choir; English Baroque Soloists; cond. by John Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) he visited the St David's Festival in West Wales with the Eliot Gardiner 16 Minuets (K.176) (excerpts) Nos.1-4 orchestra, taking the 'Haffner' symphony. Today he conducts Slovak Sinfonietta, cond. Tara Krysa the players in Symphony No. 25, written when Mozart was a 01:50AM teenager. It's his first symphony in a minor key, and maybe the Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) 05:51AM passion and turbulence we hear in the outer movements a young Piano Sonata in C minor (K. 457) (1784) Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) man struggling out of his adolescence. Denis Burstein (piano) Quartet for strings in B flat major (K.458) "Hunt" Quatuor Mosaïques MOZART 02:15AM Violin Concerto No. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

143-Signs-Games-And-Messages

JenniferKoh_Signs_MECH_OL_r1.indd 1 8/19/2013 2:43:06 PM Producer & Engineer Judith Sherman Editing Bill Maylone Recorded American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City, April 27–28 and v LEOŠ JANÁCEK (1854–1928) October 14–17, 2012 Sonata for Violin and Piano JW VII/7 (17:29) Front Cover Design Sue Cottrill 1 I. Con moto (4:48) 3 III. Allegretto (2:38) Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Nancy Bieschke 2 II. Ballada: Con moto (5:13) 4 IV. Adagio (4:39) Cover Photography Jürgen Frank GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926) 5 Doina (from Játékok, Vol. VI)* (2:28) 6 The Carenza Jig (from Signs, Games and Messages)† (0:45) Tre Pezzi for Violin and Piano, Op. 14e (5:31) 7 I. Öd und traurig (2:14) Cedille Records is a trademark of Cedille Chicago, NFP (fka The Chicago Classical Recording 8 II. Vivo (1:06) Foundation), a not-for-profit organization devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles 9 III. Aus der Ferne: sehr leise, äusserst langsam (2:05) in the Chicago area. Cedille Chicago’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants ** from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Irving Harris bk Fundamentals No. 2 (from Játékok, Vol. VI) (0:30) † Foundation, Mesirow Financial, NIB Foundation, Negaunee Foundation, Sage Foundation, and the bl In memoriam Blum Tamás (from Signs, Games and Messages) (3:08) * Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. bm Like the flowers of the field... (from Játékok, Vol. V) (1:52) † bn Postcard to Anna Keller (from Signs, Games and Messages) (0:30) ** bo A Hungarian Lesson for Foreigners (from Játékok, Vol. -

Taking Flight Beginning with a Tribute to Lindbergh, the St

TAKING FLIGHT BEGINNING WITH A TRIBUTE TO LINDBERGH, THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY EXPRESSES THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS. BY EDDIE SILVA DILIP VISHWANAT David Robertson Begin with a new beginning. The St. Louis Symphony’s 2016-17 season, its 137th, starts with the turn of a propeller, a steep rise into uncluttered skies, and a lonely, perilous journey that changed how people lived, thought, and dreamed. Charles Lindbergh’s silvery craft was christened The Spirit of St. Louis, and pilot and aircraft made their historic flight together across the Atlantic 90 years ago. The name “Spirit of St. Louis” also reflects upon the daring and innovation of a few St. Louisans early in the 20th century. It also speaks to St. Louis now, near the beginning of a new century amidst a whirlwind of innovation that turns more swiftly than a propeller. The St. Louis Symphony, Music Director David Robertson has remarked often, embodies that spirit: innovative, daring, risk-taking, enduring, agile, resourceful—give it an engine and a pair of wings and you’ll see Paris by morning. Kurt Weill’s The Flight of Lindbergh opens the 2016-17 season (September 16-17). Described as a “radio cantata,” it is one of the early collaborations between Weill and Bertolt Brecht, who created the classic The Threepenny Opera as well as other distinctive Brecht/Weill productions. KMOX’s Charlie Brennan provides the radio expertise as narrator of The Flight of Lindbergh. This 1929 work, written in the flush of inspiration that followed Lindbergh’s 6 Taking Flight achievement, will feel fresh, new, and innovative in 2016. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Friday 8 May 2020

Koanga - New Zealand SO/John Hopkins Zealand National Youth Choir/Karen (EX Tartar TRL 020) Grylls (TRUST MMT 2016) 2:00 approx ELGAR: Nursery Suite - New Zealand JOPLIN: Maple Leaf Rag; Magnetic Rag (2) SO/James Judd (Naxos 8.557166) - Elizabeth Hayes (pno) (QUARTZ QTZ 2005) COPLAND: Down a Country Lane - Saint Friday 8 May 2020 BECK: Sinfonia in G minor Op 3/3 - Paul CO/Hugh Wolff (Teldec 77310) Toronto CO/Kevin Mallon (Naxos 5:00 approx 12:00 Music Through the Night 8.570799) BRAHMS: Violin Sonata No 2 in A Op 100 - RAMEAU: The Entrance of Polyhymnia, GAY: Virgins Are Like The Fair Flow'r, from Tasmin Little (vln), Piers Lane (pno) from Les Boréades - Ensemble The Beggar's Opera - Kiri Te Kanawa (sop), (Chandos CHAN 10977) Pygmalion/Raphaël Pichon (Harmonia National Phil/Richard Bonynge (Decca 475 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: In the Fen Country - Mundi HMM902288) 459) London Festival Orch/Ross Pople (ASV CD DELIUS: Walk to the Paradise Garden - DETT: Eight Bible Vignettes - Denver DCA 779) Symphony Nova Scotia/Georg Tintner Oldham (piano) (New World NW 367) ANONYMOUS: Masque Dances - Alison (CBC Records SMCD 5134) HAN KUN SHA: Shepherd's Song - Melville (recorder), Margaret Gay (cello), CIMAROSA: Concerto in G for two flutes - Shanghai Quartet (Delos DE 3308) Peter Lehman (theorbo), Valerie Weeks Mathieu Dufour (fl), Alex Klein (ob), Czech 3:00 approx (hpschd) (EBS EBS 6016) National SO/Paul Freeman (Cedille CDR TELEMANN: Trumpet Concerto in D - DELIUS arr Fenby: Serenade, from Hassan 90000 080) Niklas Eklund (baroque tpt), - Julian Lloyd Webber