JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 88

BOSTON SYMPHONY v^Xvv^JTa Jlj l3 X JlVjl FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 PAIGE OBRION RUSSELL Insurance Since 1876 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ROBERT H.GARDINER Vice-President EDWARD M. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

Taking Flight Beginning with a Tribute to Lindbergh, the St

TAKING FLIGHT BEGINNING WITH A TRIBUTE TO LINDBERGH, THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY EXPRESSES THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS. BY EDDIE SILVA DILIP VISHWANAT David Robertson Begin with a new beginning. The St. Louis Symphony’s 2016-17 season, its 137th, starts with the turn of a propeller, a steep rise into uncluttered skies, and a lonely, perilous journey that changed how people lived, thought, and dreamed. Charles Lindbergh’s silvery craft was christened The Spirit of St. Louis, and pilot and aircraft made their historic flight together across the Atlantic 90 years ago. The name “Spirit of St. Louis” also reflects upon the daring and innovation of a few St. Louisans early in the 20th century. It also speaks to St. Louis now, near the beginning of a new century amidst a whirlwind of innovation that turns more swiftly than a propeller. The St. Louis Symphony, Music Director David Robertson has remarked often, embodies that spirit: innovative, daring, risk-taking, enduring, agile, resourceful—give it an engine and a pair of wings and you’ll see Paris by morning. Kurt Weill’s The Flight of Lindbergh opens the 2016-17 season (September 16-17). Described as a “radio cantata,” it is one of the early collaborations between Weill and Bertolt Brecht, who created the classic The Threepenny Opera as well as other distinctive Brecht/Weill productions. KMOX’s Charlie Brennan provides the radio expertise as narrator of The Flight of Lindbergh. This 1929 work, written in the flush of inspiration that followed Lindbergh’s 6 Taking Flight achievement, will feel fresh, new, and innovative in 2016. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

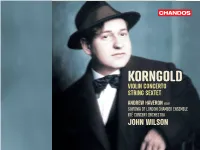

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College.