The Oboe Concerto of John Harbison: a Guide to Analysis, Performance, and the Collaboration with Oboist, William Bennett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

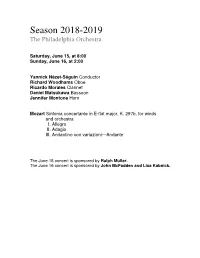

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Radio 3 Listings for 3 – 9 May 2008 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 03 MAY 2008 SUNDAY 04 MAY 2008 to Supper

Radio 3 Listings for 3 – 9 May 2008 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 03 MAY 2008 SUNDAY 04 MAY 2008 to Supper. SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00b1npd) SUN 00:00 The Early Music Show (b007n30p) Interwoven with the poetry is music such as Schubert's Trout Including 1.00 Sibelius, Grieg, Mozart, Hindemith, Durufle. Emilio's Wedding Quintet, the chorus in Strauss' Die Fledermaus where the guests 3.25 Bach, Shostakovich, Rossini, Purcell, Wolf. 5.00 look forward to supper, and Biber's Mensa Sonora (music Kabalevsky, Purcell, Barber, Vivaldi, Biber, Sibelius, Chopin. Emilio's Wedding: Catherine Bott looks back on the life of suitable to accompany aristocratic dining) Emilio de Cavalieri, famous for co-ordinating the music for one of the most lavish wedding celebrations in history. There's the "Rice aria" from Rossini's Tancredi, which the food SAT 05:00 Through the Night (b00b1nq1) loving composer apparently composed whilst waiting for his Through the Night risotto to cook and Nellie Melba, the soprano who gave her SUN 01:00 Through the Night (b00b525r) name to the Peach Melba, sings the Melba Waltz. John Shea concludes the programme with music by Kabalevsky, Including 1.00 Berg, Strauss, Jernefelt, Debussy, Satie. 3.10 Purcell, Barber, Vivaldi, Biber, Sibelius, Chopin, Browne, Ravel, Clerambault, Brahms, Beethoven, Sibelius. 5.00 Rimsky- Plus popular food music by Fats Waller (Hold Tight I Want Faure and Kodaly. Korsakov, Schubert, Mozart, Bach, Haydn, Mendelssohn. Some Seafood Mama), The Beatles (Savoy Truffle) and Bob Dylan (Country Pie). SAT 07:00 Breakfast (b00b5d6f) SUN 05:00 Through the Night (b00b525t) Perhaps the most peculiar choice is a medieval song about eggs Including Vivaldi: Trio in C, RV82. -

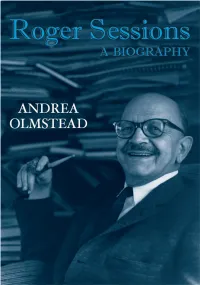

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Finale Transposition Chart, by Makemusic User Forum Member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans

Finale Transposition Chart, by MakeMusic user forum member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans. Sounding Written Inter- Key Usage (Some Common Western Instruments) val Alter C Up 2 octaves Down 2 octaves -14 0 Glockenspiel D¯ Up min. 9th Down min. 9th -8 5 D¯ Piccolo C* Up octave Down octave -7 0 Piccolo, Celesta, Xylophone, Handbells B¯ Up min. 7th Down min. 7th -6 2 B¯ Piccolo Trumpet, Soprillo Sax A Up maj. 6th Down maj. 6th -5 -3 A Piccolo Trumpet A¯ Up min. 6th Down min. 6th -5 4 A¯ Clarinet F Up perf. 4th Down perf. 4th -3 1 F Trumpet E Up maj. 3rd Down maj. 3rd -2 -4 E Trumpet E¯* Up min. 3rd Down min. 3rd -2 3 E¯ Clarinet, E¯ Flute, E¯ Trumpet, Soprano Cornet, Sopranino Sax D Up maj. 2nd Down maj. 2nd -1 -2 D Clarinet, D Trumpet D¯ Up min. 2nd Down min. 2nd -1 5 D¯ Flute C Unison Unison 0 0 Concert pitch, Horn in C alto B Down min. 2nd Up min. 2nd 1 -5 Horn in B (natural) alto, B Trumpet B¯* Down maj. 2nd Up maj. 2nd 1 2 B¯ Clarinet, B¯ Trumpet, Soprano Sax, Horn in B¯ alto, Flugelhorn A* Down min. 3rd Up min. 3rd 2 -3 A Clarinet, Horn in A, Oboe d’Amore A¯ Down maj. 3rd Up maj. 3rd 2 4 Horn in A¯ G* Down perf. 4th Up perf. 4th 3 -1 Horn in G, Alto Flute G¯ Down aug. 4th Up aug. 4th 3 6 Horn in G¯ F# Down dim. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with Guest Janice Felty, Mezzo-Soprano Now Again

Network for Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with guest Janice Felty, mezzo-soprano Now Again Music by Bernard Rands Network for New Music Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor www.albanyrecords.com TROY1194 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 with guest Janice Felty, tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd mezzo-soprano tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. The story is probably apocryphal, but it was said his students at Harvard had offered a prize to anyone finding a wantonly decorative note or gesture in any of Bernard Rands’ music. Small ensembles, single instrumental lines and tones convey implicitly Rands’ own inner, but arching, songfulness. In his recent songs, Rands has probed the essence of letter sounds, silence and stress in a daring voyage toward the center of a new world of dramatic, poetic expression. When he wrote “now again”—fragments from Sappho, sung here by Janice Felty, he was also A conversation between composer David Felder and filmmaker Elliot Caplan about Shamayim. refreshing his long association with the virtuosic instrumentalists of Network for New Music, the Philadelphia ensemble marking its 25th year in this recording. These songs were performed in a 2009 concert for Rands’ 75th birthday — and offer no hope for winning the prize for discovering extraneous notes or gestures. They offer, however, an intimate revelation of the composer’s grasp of color and shade, his joy in the pulsing heart, his thrill at the glimpse of what’s just ahead. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post.