Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

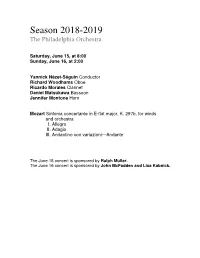

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

Im Dienste Einer Staatsidee

Wiener Musikwissenschaftliche Beiträge Band 24 Herausgegeben von Gernot Gruber und Theophil Antonicek Forschungsschwerpunkt Musik – Identität – Raum Band 1 Elisabeth Fritz-Hilscher (Hg.) IM DIENSTE EINER STAATSIDEE Künste und Künstler am Wiener Hof um 1740 2013 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar Gedruckt mit der Unterstützung durch den Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung : Mittelmedaillon des Deckenfreskos im Festsaal der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ehemals Alte Universität) von Gregorio Guglielmi nach einem Programmentwurf von Pietro Metastasio (Rekonstruktion nach dem Brand von 1961 durch Paul Reckendorfer) © ÖAW © 2013 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H., Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung : General Nyomda kft., H-6728 Szeged Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-78927-7 Inhalt Vorwort .................................... 7 Grete Klingenstein : Bemerkungen zur politischen Situation um 1740 ..... 11 Literatur Alfred Noe : Die italienischen Hofdichter. Das Ende einer Ära ......... 19 Wynfrid Kriegleder : Die deutschsprachige Literatur in Wien um 1740 .... 47 Kunst Werner Telesko : Herrscherrepräsentation um 1740 als „Wendepunkt“ ? Fragen zur Ikonographie von Kaiser Franz I. Stephan ............. 67 Anna Mader-Kratky : Modifizieren oder „nach alter Gewohnheit“ ? Die Auswirkungen des Regierungsantritts von Maria Theresia auf Zeremoniell und Raumfolge in der Wiener Hofburg .................... 85 Theater Andrea Sommer-Mathis : Höfisches Theater zwischen 1735 und 1745. -

1 Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music Or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting by Mary

1 Morrow, Mary Sue. “Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music, or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 6.1 (Spring 2016), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2016. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Eighteenth-Century Music in a Twenty-First Century Conservatory of Music or Using Haydn to Make the Familiar Exciting by Mary Sue Morrow University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music I. Introduction Teaching the history of eighteenth-century music in a conservatory can be challenging. Aside from the handful of music history and music theory students, your classes are populated mostly by performers, conductors, and composers who do not always find the study of music history interesting or even necessary. Moreover, when you step in front of a graduate-level class at the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati, everybody in the class is going to know all about the music of the eighteenth century: they’ve played Bach fugues and sung in Handel choruses; they’ve sung Mozart arias and played Haydn string quartets or early Beethoven sonatas. They have also been taught to revere these names as the century’s musical geniuses, but quite a number of them will admit that they are not very interested in eighteenth-century music, particularly the music from the late eighteenth-century: It is too ordinary and unexciting; it all sounds alike; it is mostly useful for teaching purposes (definitely the fate of Haydn’s keyboard sonatas and, to a degree, his string quartets). -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo

VIVACEAUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Classical music review in Supraphon recordings Photo archive PPC archive Photo Photo © Jan Houda Photo LUKÁŠ VASILEK SIMONA ŠATUROVÁ TOMÁŠ NETOPIL Borggreve © Marco Photo Photo © David Konečný Photo Photo © Petr Kurečka © Petr Photo MARKO IVANOVIĆ RADEK BABORÁK RICHARD NOVÁK CP archive Photo Photo © Lukáš Kadeřábek Photo JANA SEMERÁDOVÁ • MAREK ŠTRYNCL • ROMAN VÁLEK Photo © Martin Kubica Photo XENIA LÖFFLER 1 VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo Dear friends, of Kabeláč, the second greatest 20th-century Czech symphonist, only When looking over the fruits of Supraphon’s autumn harvest, I can eclipsed by Martinů. The project represents the first large repayment observe that a number of them have a common denominator, one per- to the man, whose upright posture and unyielding nature made him taining to the autumn of life, maturity and reflections on life-long “inconvenient” during World War II and the Communist regime work. I would thus like to highlight a few of our albums, viewed from alike, a human who remained faithful to his principles even when it this very angle of vision. resulted in his works not being allowed to be performed, paying the This year, we have paid special attention to Bohuslav Martinů in price of existential uncertainty and imperilment. particular. Tomáš Netopil deserves merit for an exquisite and highly A totally different hindsight is afforded by the unique album acclaimed recording (the Sunday Times Album of the Week, for of J. S. Bach’s complete Brandenburg Concertos, which has been instance), featuring one of the composer’s final two operas, Ariane, released on CD for the very first time. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Music of the Classical Period

2019/2020 Music of the Classical Period Code: 100641 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500240 Musicology OB 2 2 Contact Use of Languages Name: Jordi Rifé Santaló Principal working language: catalan (cat) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: Yes Some groups entirely in Spanish: No Prerequisites 1.Have a general knowledge of the History of Music, Art and Philosophy. 2.Have consolidated the bases of Harmony, Contrpunto and Musical Forms. Objectives and Contextualisation The course seeks to describe and explain the development of music and the musical phenomenon from the end of the last Baroque until the early decades of the XIX century. Therefore, it will be a contextualized journey through the most important composers, forms, genres, instruments and theories that make up the musical style of the music of the classical and musical classicism. Competences Critically analyse musical works from any of the points of view of the discipline of musicology. Developing critical thinking and reasoning and communicating them effectively both in your own and other languages. Identify and compare the different channels of reception and consumption of music in society and in culture in each period. Know and understand the historical evolution of music, its technical, stylistic, aesthetic and interpretative characteristics from a diachronic perspective. Relate concepts and information from different humanistic, scientific and social disciplines, especially the interactions which are established between music and philosophy, history, art, literature and anthropology. Relate knowledge acquired to musical praxis, working with musicians through the analysis and contextualisation of different repertoires, both related to historical music and to the different manifestations of contemporary music. -

12. (501) the Piano Was for ; the Violin Or

4 12. (501) The piano was for ______________; the violin or cello was for ___________. Who was the more Chapter 22 proficient? TQ: Go one step further: If that's true, how Instrumental Music: Sonata, Symphony, many females were accomplished concert pianists? and Concerto at Midcentury Females; males; females; that's not their role in society because the public arena was male dominated 1. [499] Review: What are the elements from opera that will give instrumental music its prominence? 13. What's the instrumentation of a string quartet? What are Periodic phrasing, songlike melodies, diverse material, the roles of each instrument? contrasts of texture and style, and touches of drama Two violins, viola, cello; violin gets the melody; cello has the bass; violin and viola are filler 2. Second paragraph: What are the four new (emboldened) items? 14. What is a concertante quartet? Piano; string quartet, symphony; sonata form One in which each voice has the lead 3. (500) Summarize music making of the time. 15. (502) When was the clarinet invented? What are the four Middle and upper classes performed music; wealthy people Standard woodwind instruments around 1780? hired musicians; all classes enjoyed dancing; lower 1710; flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon classes had folk music 16. TQ: What time is Louis XIV? 4. What is the piano's long name? What does it mean? Who R. 1643-1715 (R. = reigned) invented it? When? Pianoforte; soft-loud; Cristofori; 1700 17. Wind ensembles were found at _________ or in the __________ but _________ groups did not exist. 5. Review: Be able to name the different keyboard Court; military; amateur instruments described here and know how the sound was produced. -

Download Booklet

Classics Contemporaries of Mozart Collection COMPACT DISC ONE Franz Krommer (1759–1831) Symphony in D major, Op. 40* 28:03 1 I Adagio – Allegro vivace 9:27 2 II Adagio 7:23 3 III Allegretto 4:46 4 IV Allegro 6:22 Symphony in C minor, Op. 102* 29:26 5 I Largo – Allegro vivace 5:28 6 II Adagio 7:10 7 III Allegretto 7:03 8 IV Allegro 6:32 TT 57:38 COMPACT DISC TWO Carl Philipp Stamitz (1745–1801) Symphony in F major, Op. 24 No. 3 (F 5) 14:47 1 I Grave – Allegro assai 6:16 2 II Andante moderato – 4:05 3 III Allegretto/Allegro assai 4:23 Matthias Bamert 3 Symphony in G major, Op. 68 (B 156) 24:19 Symphony in C major, Op. 13/16 No. 5 (C 5) 16:33 5 I Allegro vivace assai 7:02 4 I Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 6 II Adagio 7:24 5 II Andante grazioso 6:07 7 III Menuetto e Trio 3:43 6 III Allegro 4:31 8 IV Rondo. Allegro 6:03 Symphony in G major, Op. 13/16 No. 4 (G 5) 13:35 Symphony in D minor (B 147) 22:45 7 I Presto 4:16 9 I Maestoso – Allegro con spirito quasi presto 8:21 8 II Andantino 5:15 10 II Adagio 4:40 9 III Prestissimo 3:58 11 III Menuetto e Trio. Allegretto 5:21 12 IV Rondo. Allegro 4:18 Symphony in D major ‘La Chasse’ (D 10) 16:19 TT 70:27 10 I Grave – Allegro 4:05 11 II Andante 6:04 12 III Allegro moderato – Presto 6:04 COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 61:35 Leopold Kozeluch (1747 –1818) 18:08 COMPACT DISC THREE Symphony in D major 1 I Adagio – Allegro 5:13 Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757 – 1831) 2 II Poco adagio 5:07 3 III Menuetto e Trio. -

Musikstunde Ignaz Holzbauer

_______________________________________________________________________________________ 2 Musikstunde Ignaz Holzbauer Alles Runde, so das Thema dieser Musikstundenwoche und meint damit, alles runde Geburtstage. Und zwar diesmal von solchen Jubilaren, die sonst immer zu kurz kommen, die allein keine komplette Sendewoche füllen könnten und es aber verdienen, dass man sie nicht ganz vergisst. William Boyce heißen sie, Ferdinand Hiller, Ambroise Thomas, Nino Rota und heute Ignaz Holzbauer. Er feiert in diesen Tagen, genauer gesagt gestern seinen 300. Geburtstag. In Wien kommt er zur Welt, also mitten im Geschehen, mitten in einer der größten Musikzentren Europas, wird getauft im Stephansdom, besucht hier auch die Universität. Aber Ignaz Holzbauer verlässt die Donaumetropole und macht sich auf den Weg zu uns ins Sendegebiet von SWR 2. Sein erstes Engagement als Hofkapellmeister führt ihn an die Stuttgarter Hofkapelle, von da aus in die Pfalz an die legendäre Mannheimer Hofkapelle. Hier bleibt er, auch als der Kurfürst nach Bayern umzieht und stirbt hoch geachtet und für damalige Verhältnisse uralt, mit 83 Jahren. Komponiert hat Ignaz Holzbauer bis kurz vor seinem Tod, auch wenn er seine Musik wegen einer Ertaubung selbst leider nicht mehr hören konnte. 1’10 Musik 1: Holzbauer:1.Satz aus der Sinfonie in d-Moll M0090682 004 2‘20 Schwungvoll und lebhaft klingen die Sinfonien des Ignaz Holzbauer, hier der 1. Satz aus seiner Sinfonie in d-Moll mit dem L’Orfeo Barockorchester unter Michi Gaigg. Ignaz Holzbauer, heute so gut wie vergessen, ist zu Lebzeiten eine Berühmtheit. Aber die Karriere fällt ihm nicht in den Schoß, er arbeitet zielstrebig drauf hin und weiß schon als Halbwüchsiger, dass sein Glück nur in der Musik liegt. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE