Augustine on Heart and Life Essays in Memory of William Harmless, S.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

To Clarify Mission of Laity

Seeschanges in catechism to clarify missionof laity By WALTERr . ABBOTT,S.J, Well knott'u tor lris actiye interest in the la1, apostolate I'novcmol)t, the 6[-.ye;rt'-old prtlatc attt'actetl attcntion last vcar rvhcu hc callctl a tnect- inS ol tlte lrlot'ttttcc laity hrs peoplc rvelc Caltlinal (lia- (lttttttcil's filst conlo Let'cato. Alchbislrop of -,scssiottttrli'or to tltc itt o|tlcl', as lte put Ilologrla i ,\r'chlrisllop [)ttt'icltr lrclici, Sct'rctar.1'(icnt'r.al ol thc it, to hi.rve,,lull knorvlcrigc" ul rii,'eopre's(r*si'cs Iillillli.,i,,il'i"li',..;').i,;..8:,lil\l tuf N1'cri. Kenr-a; Ilussian-lloln 'litular I)1'zantinc Rite Bishop An- tlt'ci Katkoff ol Nauplia; Auxil- ialv Bislrop,lcan Ilupp of I'alis; llisltr.rp Flrnilio (luano o[ Lilolno. autl trvo othet' Italiatr prclates- Attxiliarl Bishop 14nlico Ilarto- lctti of I-uecl an<l Auxiliarl' Rish- Desclibing titt: pt'ttct'ss ol colll' up .\ntonio ..\rrgioni oI I]rsa. Intttricntion llctrvctrtt lrtopltl atttl , rr.rorrHr.ie enuAnv Itisltop as a cotttittttitrg tltto. Ilc s. re6t- "thc _1"l_11-" __ _ saitl pcople hitt'e a t'igltt ltt spenk to their bislrop. for ltrr is , " the ir' [atltct'. TTATOR AC TIIE IlE tr.lEI\i 7" ARCHBISHOP ["hlit sartl ltc folcsau, tlta{ thctc n'ould havc (o Lo chlttgcs irr tht: catccltisnt itl order to set [()fth the llasit tltc' ologl' o{ llrc (llrurch logalrlitlg tlttl New spirit of charity lolc ol tlrc laitt in lattgtragc tltat u'o'rlrl rrtcct lltc t:xpectaliotts o[ llt(' pcol)lc. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

Bulgakov Handbook

October 21 G.† Our Ven. Father Hilarion the Great He was born in Palestine, near Gaza City, studied the sciences and was baptized in Alexandria. When he was 15 years old, Hilarion heard about Ven. Anthony the Great and admiring "Anthony's spiritually divine, virtuous way of life" went to him. Having returned home with a blessing from Ven. Anthony, Hilarion found that his parents died and, "despising all worldly pleasures", distributed all his remaining inherited estate to the poor and in a certain deserted place was devoted entirely to prayer and abstinence. St. Hilarion struggled a lot with unclean thoughts, who confused his mind and inflamed his body; but he exhausted his body with work and drove away these thoughts by prayer and meditation on God. The holy hermit suffered much from demons and more than once while standing in prayer heard the crying of children, sobbing of women, roaring of lions and other wild animals, awful noises and confusion presented by the demons. But he did not fear the "demonic traps" and through fervent prayer conquered the "gloomy enemy powers". Once, robbers set upon the holy ascetic, but he by the power of his word convinced them to leave their vice and to lead a good life. Soon all of Palestine heard about the holy hermit's life and many began to come to him for healing of body and soul, but others wished to save their soul under his direction. With his blessing many monasteries were built in Palestine, and going from one monastery to another, he established a strict ascetic paradigm of life in them, having become the same kind of trainer for those seeking salvation in Palestine as Ven. -

The Image of Justinianic Orthopraxy in Eastern Monastic Literature

The Image of Justinianic Orthopraxy in Eastern Monastic Literature 2 From 535 to 546, the emperor Justinian issued a series of imperial constitutions which sought to regulate the activities of monks and monasteries. Unprecedented in its scope, this legislative programme marked an attempt by the emperor to bring ascetics firmly under the purview of his government. Taken together, its rulings legislated on virtually every aspect of the ascetic life, prescribing a detailed model of ‘orthopraxy,’ or correct behaviour, to which the emperor demanded monks adhere. However, whilst it is clichéd to evoke Justinian’s status as a reformer of the law, scholars continue to view these orthopraxic rulings with some uncertainty. This is a reflection, in part, of the difficulties faced when attempting to judge the extent to which they were ever adopted or enforced. Studies of the emperor’s divisive religious policies have tended to focus instead upon matters of doctrine and, in particular, Justinian’s efforts to enforce his view of orthodoxy upon anti-Chalcedonian, monastic dissidents. This paper builds upon recent work to argue that the effects of Justinian’s monastic legislation were, in fact, widely felt.1 It will argue that accounts of the mid-sixth century by Eastern monastic authors reveal widespread familiarity with the rulings on ascetic practice contained in the emperor’s Novels. Their reception reveals the extent of imperial power over ascetics during this period, frequently presented as one in which the ‘holy man’ exercised almost boundless social and spiritual authority. I will concentrate on three main examples to illustrate this point, chosen to represent a suitable cross-section of the contemporary monastic movement: Cyril of Scythopolis’ Life of Sabas, the Life of Z‘ura in the Lives of the Eastern Saints by John of Ephesus, and the Coptic texts which detail the career of the Egyptian monastic leader, Abraham of Farshut.2 ORTHOPRAXY IN JUSTINIAN’S MONASTIC LEGISLATION Firstly, however, we must discuss Justinian’s monastic laws in greater detail. -

The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St

HOLY PSALMODY OF Kiahk According to the orders of the Coptic Orthodox Church First Edition }"almwdi8a Ecouab 8nte pi8abot ak <oi 8M8vrh+ 8etaucass 8nje nenio+ 8n+ek8klhsi8a 8nrem8n<hmi M St. George & St. Joseph Coptic Orthodox Church K The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St. George and St Joseph Church Montreal, Canada Kiahk 1724 A. M., December 2007 A. D. St George & St Joseph Church 17400 Boul. Pierrefonds Pierrefonds, QC. CANADA H9J 2V6 Tel.: (514) 626‐6614, Fax.: (514) 624‐8755 http://www.stgeorgestjoseph.ca Behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is His Name. Luke 1: 48 - 49 Hhppe gar isjen +nou senaermakarizin 8mmoi 8nje nigene8a throu@ je afiri nhi 8nxanmecnis+ 8nje vh etjor ouox 8fouab 8nje pefran. His Holiness Pope Shenouda III Pope of Alexandria, and Patriarch of the see of saint Mark Peniwt ettahout 8nar,hepiskopos Papa abba 0enou+ nimax somt Preface We thank the Lord, our God and Saviour, for helping us to start this project. In this first edition, our goal was to gather pre‐translated hymns, and combine them with Midnight Praises in one book. God willing, our final goal is to have one book where the congregation can follow all the proceedings without having to refer to numerous other sources. We ask and pray to our Lord to help us complete this project in the near future. The translated material in this book was collected from numerous sources: Coptichymns.net web site Kiahk Praises, by St George & St Shenouda Church The Psalmody of Advent, by William A. -

Shenoute Paper Draft

Mimetic Devotion and Dress in Some Monastic Portraits from the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit* Thelma K. Thomas For the monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit in Middle Egypt there is good archaeological documentation, a wealth of primary written sources mainly in the form of inscriptions, and a long history of scholarship illuminating both the site and the paintings at the center of this study.1 The archaeological site (figure 1) is extensive, and densely built. The many paintings, usually dated to the sixth and seventh centuries, survive in varying states of preservation from a range of functional contexts, however in this discussion I focus on * I am grateful to Hany Takla for inviting me to present a version of this article at the Twelfth St. Shenouda-UCLA Conference of Coptic Studies in July 2010. I owe thanks as well to Jenn Ball, Betsy Bolman, Jennifer Buoncuore, Mariachiara Giorda, Tom Mathews, and Maged Mikhail. Many of the issues considered here will be addressed more extensively in a book-length study, Dressing Souls, Making Monks: Monastic Habits of the Desert Fathers. 1 The main archaeological publications include: Jean Clédat, Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouit, Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. 12 (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, 1904); Jean Clédat, Le monastère et la nécropole de Baouit, Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. 39 (Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1916); Jean Maspéro, “Fouilles executées à Baouit, Notes mises en ordre et éditées par Etienne Drioton,” Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, Memoires, vol. -

A Tribute to SAC's First Registrar Fr Macarius Wahba

ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁThe Newsletter of SAC Issue 8, December 2020 A Tribute to SAC’s first registrar Fr Macarius Wahba STUDENT REFLECTIONS Congratulations to SAC HIGHLIGHTS OF 2020 Graduates 2020 SAC’s Free Short Online VCE STUDENTS TAKE ON Courses CERT. III IN CHRISTIAN MINISTRY & THEOLOGY ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁ The Newsletter of SAC Issue 8, December 2020 ISSN 2205-2763 (Online) Published by SAC Press 100 Park Rd, Donvale, VIC 3111 Editor: Lisa Agaiby Graphic Design: Bassem Morgan Photo Credits: Bassem Morgan, Shady Nessim, John McDowell, Fr Jacob Joseph, Benjamin Ibrahim, Siby Varghese, Andrea Sherko, Cecily Clark, and Fr Nebojsa Tumara © SAC – A College of the University of Divinity ABN 61 153 482 010 CRICOS Provider 01037A, 03306B www.sac.edu.au/koinonia Feedback: [email protected] ⲕⲟⲓⲛⲱⲛⲓⲁ is available in electronic PDF format CONTENTS A Message from the Principal 3 A Tribute to SAC’s First Registrar Fr Macarius Wahba 4 Congratulations to all our SAC Graduates in 2020! 5 Introducing our New Academic Dean: Prof. John Mcdowell 6 Introducing our First Lecturer in Missiology: Fr Dr Jacob Joseph 7 Introducing our Tutor: Shady Nessim 8 Priesthood Ordination of Rev. Fr Jonathan Awad 9 Highlights of 2020 10 VCE Students Take on Cert. III in Christian Ministry & Theology 10 SAC Offers Free Short Online Courses 12 Online Public Lectures 13 International Conferences 14 Manuscript Project at the Monastery of St Paul the Hermit – An Update 15 Student Reflections 16 Reflections on “Coptic Iconography I” by Siby Varghese 16 Reflections on “Coptic Iconography I” by Benjamin Ibrahim 17 Reflections on “Philosophy For Beginners” by Andrea Sherko 18 Reflections on “Atheism” by Andrew E. -

The Forerunner

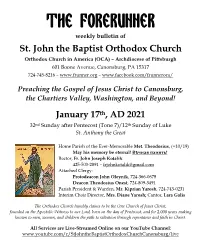

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

ABSTRACT the Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories Of

ABSTRACT The Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret Scott A. Rushing, Ph.D. Mentor: Daniel H. Williams, Ph.D. This dissertation analyzes the transposition of the apostolic tradition in the fifth-century ecclesiastical histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. In the early patristic era, the apostolic tradition was defined as the transmission of the apostles’ teachings through the forms of Scripture, the rule of faith, and episcopal succession. Early Christians, e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen, believed that these channels preserved the original apostolic doctrines, and that the Church had faithfully handed them to successive generations. The Greek historians located the quintessence of the apostolic tradition through these traditional channels. However, the content of the tradition became transposed as a result of three historical movements during the fourth century: (1) Constantine inaugurated an era of Christian emperors, (2) the Council of Nicaea promulgated a creed in 325 A.D., and (3) monasticism emerged as a counter-cultural movement. Due to the confluence of these sweeping historical developments, the historians assumed the Nicene creed, the monastics, and Christian emperors into their taxonomy of the apostolic tradition. For reasons that crystallize long after Nicaea, the historians concluded that pro-Nicene theology epitomized the apostolic message. They accepted the introduction of new vocabulary, e.g. homoousios, as the standard of orthodoxy. In addition, the historians commended the pro- Nicene monastics and emperors as orthodox exemplars responsible for defending the apostolic tradition against the attacks of heretical enemies. The second chapter of this dissertation surveys the development of the apostolic tradition. -

Conversations an E-Journal from the Uniting Church Centre for Theology & Ministry 1 Morrison Close Parkville, VIC, 3052 [email protected]

Conversations An e-journal from the uniting church Centre for Theology & Ministry 1 Morrison Close Parkville, VIC, 3052 [email protected] Accountability in Discernment: Our Life and Death is in Our Neighbour Introduction ‘Discernment’ is something of buzz word. Reports of it abound in church circles accompanied by wry smiles: that someone has discerned ‘their’ call to study overseas, to offer new programs in inspiring locations. It has even become a lunchtime joke: ‘Have you discerned your sandwich options?’ While Christian tradition is clear that all of these choices, from diet to institutional investment to individual vocation, are indeed matters for discernment, applying the buzz word rightly is no laughing matter. Against a wide‐spread assumption that discernment is an individual concern into which the Christian community should not intrude or even enquire too closely, the monastic tradition points to an accompanying vocabulary of other terms. Ancient catch‐cries from the Christian tradition link ‘discernment’ powerfully to ‘humility’, ‘obedience’, ‘accountability’, and ‘the infinite horizon of God’s Reign’. Woven together these qualities and attitudes give a rich texture to the patterns of faithful discernment. These less marketable but deeply resonant terms offer checks and balances to the tendency to see discernment as a personal matter for an individual and God. Authentic discernment is a spiritual gift and fruit of humility, made possible by a loving community. This article explores the monastic understanding of discernment and the role of accountability in ensuring good decisions. It identifies two paradoxes. Firstly, while individuals who seek God are called to ask above all ‘Who am I?’, they never discover their true selves alone, as self‐authorising mavericks, but always in community and in the neighbour. -

St. Andrew's Roman Catholic Church

St. Andrew’s Roman Catholic Church th 480 East 47 Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. V5W 2B4 Phone 604.327.2824 Fax 604.327.8067 [email protected] standrewsvan.com Email Website OFFICE HOURS PASTOR: REV. JOE NGUYEN ASSISTANT PASTOR: REV. TOMSON EGIRIOUS Monday to Friday – Office Manager Alma 9am- Abarquez12pm & 1pm - 5pm School Principal Peter Veltri 604.325.6317 Office Volunteers Thelma Aldaba P.R.E.P. Coordinator Ana Alayan Nita Alojado R.C.I.A. Coordinator Father Tomson WELCOME OFFICE HOURS FUNERALS, If you are new to our parish, please Tuesday to Friday – ANOINTING OF THE SICK, be sure to register, complete the 10am to 12pm & 1pm to 4pm COMMUNION FOR ELDERLY, registration form and get Sunday AND HOUSE BLESSINGS donation envelope. MASS TIMES Contact one of the priests anytime. Registration forms are available at ~IN-PERSON ~ the Information Centre, or at the entrance to the Church. Saturday (anticipated) – 5pm RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Sunday – 9am, 11am & 4pm If you are moving from the parish, Parish Religious Education Program changing address, or phone #, please ~LIVESTREAMED~ (P.R.E.P.) Classes (2 sessions) on notify the Parish Office. Office Volunteer: Kit Mykyte Saturday (anticipated) R.C.I.A. – 5pm Coordinator : BobSundays Mitchell for Grades 1 to 7, from Sunday – 11am October 2020 to June 2021. SACRAMENTS For more information, please contact Walk-Up Holy Communion Ana Alayan @ 604.872.2900. BAPTISM (Gym Parking Lot) Last Saturday of the months of - 6:15pm to 6:45pm (Saturday) January, March, May, September, and Rite of Christian Initiation of - 12:15pm to 12:45pm (Sunday) November @ 11am.