A New Decade for Social Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia Beyond Reformasi: Necessity and the “De-Centering” of Democracy

INDONESIA BEYOND REFORMASI: NECESSITY AND THE “DE-CENTERING” OF DEMOCRACY Leonard C. Sebastian, Jonathan Chen and Adhi Priamarizki* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TRANSITIONAL POLITICS IN INDONESIA ......................................... 2 R II. NECESSITY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: THE GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC CONTEXT FOR DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA .................... 7 R III. NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ................... 12 R A. What Necessity Inevitably Entailed: Changes to Defining Features of the New Order ............. 12 R 1. Military Reform: From Dual Function (Dwifungsi) to NKRI ......................... 13 R 2. Taming Golkar: From Hegemony to Political Party .......................................... 21 R 3. Decentralizing the Executive and Devolution to the Regions................................. 26 R 4. Necessary Changes and Beyond: A Reflection .31 R IV. NON NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ............. 32 R A. After Necessity: A Political Tug of War........... 32 R 1. The Evolution of Legislative Elections ........ 33 R 2. The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections ...................................... 44 R a. The 2004 Direct Presidential Elections . 47 R b. The 2009 Direct Presidential Elections . 48 R 3. The Emergence of Direct Local Elections ..... 50 R V. 2014: A WATERSHED ............................... 55 R * Leonard C. Sebastian is Associate Professor and Coordinator, Indonesia Pro- gramme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of In- ternational Studies, Nanyang Technological University, -

Gus Dur, As the President Is Usually Called

Indonesia Briefing Jakarta/Brussels, 21 February 2001 INDONESIA'S PRESIDENTIAL CRISIS The Abdurrahman Wahid presidency was dealt a devastating blow by the Indonesian parliament (DPR) on 1 February 2001 when it voted 393 to 4 to begin proceedings that could end with the impeachment of the president.1 This followed the walk-out of 48 members of Abdurrahman's own National Awakening Party (PKB). Under Indonesia's presidential system, a parliamentary 'no-confidence' motion cannot bring down the government but the recent vote has begun a drawn-out process that could lead to the convening of a Special Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) - the body that has the constitutional authority both to elect the president and withdraw the presidential mandate. The most fundamental source of the president's political vulnerability arises from the fact that his party, PKB, won only 13 per cent of the votes in the 1999 national election and holds only 51 seats in the 500-member DPR and 58 in the 695-member MPR. The PKB is based on the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a traditionalist Muslim organisation that had previously been led by Gus Dur, as the president is usually called. Although the NU's membership is estimated at more than 30 million, the PKB's support is drawn mainly from the rural parts of Java, especially East Java, where it was the leading party in the general election. Gus Dur's election as president occurred in somewhat fortuitous circumstances. The front-runner in the presidential race was Megawati Soekarnoputri, whose secular- nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) won 34 per cent of the votes in the general election. -

Waiting on Washington: Southeast Asia Hopes for a Post-Election Boost in Us Relations

US-SOUTHEAST ASIA RELATIONS WAITING ON WASHINGTON: SOUTHEAST ASIA HOPES FOR A POST-ELECTION BOOST IN US RELATIONS CATHARIN DALPINO, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY The resurgent COVID-19 pandemic and US elections constrained the conduct of US relations with Southeast Asia and of regional affairs more broadly in the final months of 2020. Major conclaves were again “virtual”, including the ASEAN Regional Forum, the East Asia Summit. and the APEC meeting. Over the year, ASEAN lost considerable momentum because of the pandemic, but managed to oversee completion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November. Some modest gains in US-Southeast Asian relations were realized, most notably extension of the US-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) for another six months, an opportunity for Manila and the new administration in Washington to put the VFA—and the US-Philippines alliance more broadly—on firmer ground. Another significant step, albeit a more controversial one, was the under-the-radar visit to Washington of Indonesian Defense Minister, Prabowo Subianto, in October. This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 22, No. 3, January 2022. Preferred citation: Catharin Dalpino, “US-Southeast Asia Relations: Waiting on Washington: Southeast Asia Hopes for a Post-Election Boost in US Relations,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp 59-68. US- SOUTHEAST ASIA RELATIONS | JANUARY 202 1 59 As Southeast Asian economies struggled under challenges of distribution and vaccinating their the crush of COVID-19, they looked to publics. The pace of vaccination across the Washington for opportunities to “decouple” region is likely to vary widely: Indonesian from China through stronger trade and officials estimate that a nationwide vaccine investment with the United States. -

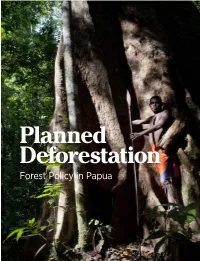

Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua | 1

PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 1 Planned Deforestation Forest Policy in Papua PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 CITATION: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Planned Deforestation: Forest Policy in Papua. February, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Dalam Bahasa Indonesia: Koalisi Indonesia Memantau. 2021. Menatap ke Timur: Deforestasi dan Pelepasan Kawasan Hutan di Tanah Papua. Februari, 2021. Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo cover: Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace PLANNED DEFORESTATION: FOREST POLICY IN PAPUA | 3 1. INDONESIAN DEFORESTATION: TARGETING FOREST-RICH PROVINCES Deforestation, or loss of forest cover, has fallen in Indonesia in recent years. Consequently, Indonesia has received awards from the international community, deeming the country to have met its global emissions reduction commitments. The Norwegian Government, in line with the Norway – Indonesia Letter of Intent signed during the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency, paid USD 56 million,1 equivalent to IDR 812 billion, that recognizes Indonesia’s emissions achievements.2 Shortly after that, the Green Climate Fund, a funding facility established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), agreed to a funding proposal submitted by Indonesia for USD 103.8 million3, equivalent to IDR 1.46 trillion, that supports further reducing deforestation. 923,050 923,550 782,239 713,827 697,085 639,760 511,319 553,954 508,283 494,428 485,494 461,387 460,397 422,931 386,328 365,552 231,577 231,577 176,568 184,560 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Figure 1. Annual deforestation in Indonesia from 2001-2019 (in hectares). Deforestation data was obtained by combining the Global Forest Change dataset from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) and land cover maps from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF). -

Report: from Quota Affirmation to Helping Female Candidates Win in the 2019 Legislative Elections the Economy Monitoring the 16Th Economic Policy Package

Volume XII, No. 2 - March 2018 ISSN 1979-1976 Monthly Review on Economic, Legal, Security, Political, and Social Affairs Main Report: From Quota Affirmation to Helping Female Candidates Win in the 2019 Legislative Elections The Economy Monitoring the 16th Economic Policy Package . Challenges in Enhancing the Role of E-Commerce in Indonesia . Politics The Threats of Hate Speech in Political Years . Criticizing the Rule Prohibiting Campaign in the Period after the . Parties Contesting the 2019 Elections are Verified Social Identifying Work Motivation of Health Workers . in Indonesian Remote Areas Protecting Women from Sexual Harassment in KRL . Problems Facing the KLJ (Jakarta Senior Citizen Card) in 2018 . ISSN 1979-1976 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................ 1 MAIN REPORT From Quota Affirmation to Helping Female Candidates Win in the 2019 Legislative Elections .................................. 2 THE ECONOMY Monitoring the 16th Economic Policy Package ...................... 5 Challenges in Enhancing the Role of E-Commerce in Indonesia 9 POLITICS The Threats of Hate Speech in Political Years ....................... 12 Criticizing the Rule Prohibiting Campaign in the Period after the Parties Contesting the 2019 Elections are Verified ............ 15 SOCIAL Identifying Work Motivation of Health Workers in Indonesian Remote Areas ................................................................. 19 Protecting Women from Sexual Harassment in KRL ............ 22 Problems Facing the KLJ (Jakarta Senior -

And During the (1998-Reformasi Era (1998—2006)

CHAPTER IV OPPORTUNISTIC SUBALTERN’S NEGOTIATIONS DURING THE NEW ORDER ERA (1974-1998) AND DURING THE (1998-REFORMASI ERA (1998—2006) What happened in West Kalimantan from early 1998 to 2006 was a distorted mirror image of what happened in Jakarta from early 1997 to 2004 (the return of the former government party Golkar, or at least its pro-development/anti-poor policies, to national politics). The old power, conveniently setting up scapegoats and places to hide, returned slowly and inconspicuously to the political theater. On the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI, or Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia) anniversary on 5 October 1999, its Supreme Commander General Wiranto, a protégé of former president Suharto, published a book that outlined the new, formal policy of the Armed Forces (entitled “ABRI Abad XXI: Redefinisi, Reposisi, dan Reaktualisasi Peran ABRI dalam Kehidupan Bangsa” or Indonesian Armed Forces 21st Century: Redefinition, Reposition, and Re-actualization of its Role in the Nation’s Life). Two of the most important changes heralded by the book were first, a new commitment by the Armed Forces (changed from ABRI to TNI, or Tentara Nasional Indonesia, Indonesian National Soldier) to detach itself from politics, political parties and general elections and second, the eradication of some suppressive agencies related to civic rules and liberties1. 1 Despite claims of its demise when the Berlin Wall was dismantled in 1989, the Cold War had always been the most influential factor within the Indonesian Armed Forces’ doctrines. At the “end of the Cold War” in 1989, the Indonesia Armed Forces invoked a doctrine related to the kewaspadaan (a rather paranoid sense of danger) to counter the incoming openness (glastnost) in Eastern Europe. -

Who Owns the Broadcasting Television Network Business in Indonesia?

Network Intelligence Studies Volume VI, Issue 11 (1/2018) Rendra WIDYATAMA Károly Ihrig Doctoral School of Management and Business University of Debrecen, Hungary Communication Department University of Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia Case WHO OWNS THE BROADCASTING Study TELEVISION NETWORK BUSINESS IN INDONESIA? Keywords Regulation, Parent TV Station, Private TV station, Business orientation, TV broadcasting network JEL Classification D22; L21; L51; L82 Abstract Broadcasting TV occupies a significant position in the community. Therefore, all the countries in the world give attention to TV broadcasting business. In Indonesia, the government requires TV stations to broadcast locally, except through networking. In this state, there are 763 private TV companies broadcasting free to air. Of these, some companies have many TV stations and build various broadcasting networks. In this article, the author reveals the substantial TV stations that control the market, based on literature studies. From the data analysis, there are 14 substantial free to network broadcast private TV broadcasters but owns by eight companies; these include the MNC Group, EMTEK, Viva Media Asia, CTCorp, Media Indonesia, Rajawali Corpora, and Indigo Multimedia. All TV stations are from Jakarta, which broadcasts in 22 to 32 Indonesian provinces. 11 Network Intelligence Studies Volume VI, Issue 11 (1/2018) METHODOLOGY INTRODUCTION The author uses the Broadcasting Act 32 of 2002 on In modern society, TV occupies a significant broadcasting and the Government Decree 50 of 2005 position. All shareholders have an interest in this on the implementation of free to air private TV as a medium. Governments have an interest in TV parameter of substantial TV network. According to because it has political effects (Sakr, 2012), while the regulation, the government requires local TV business people have an interest because they can stations to broadcast locally, except through the benefit from the TV business (Baumann and broadcasting network. -

![At Pesantren[S] in Political Dynamics of Nationality (An Analysis of Kyai's Role and Function in Modern Education System)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0317/at-pesantren-s-in-political-dynamics-of-nationality-an-analysis-of-kyais-role-and-function-in-modern-education-system-240317.webp)

At Pesantren[S] in Political Dynamics of Nationality (An Analysis of Kyai's Role and Function in Modern Education System)

PROCEEDING | ICEISR 2018 3rd International Conference on Education, Islamic Studies and Social Sciences Research DOI: https://doi.org/10.32698/24229 Padang, July 21th - 23th 2018 Repositioning Kiyai at Pesantren[s] in Political Dynamics of Nationality (An Analysis of Kyai's Role and Function in Modern Education System) Qolbi Khoiri IAIN Bengkulu, Bengkulu, Indonesia, (e-mail) [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to reveal and explain the dynamics of kiyai pesantren[s] in relation to national politics and to review the repositioning role of kiyai in the dynamics of national politics. Despite much analysis of the role of this kiyai, the fact that the tidal position of kiyai in pesantren[s] is increasingly seen its inconsistency. This can be evidenced by the involvement of kiyai practically in politics, thus affecting the existence of pesantren[s]. The results of the author's analysis illustrate that kiyai at this time must be returning to its central role as the main figure, it is important to be done, so that the existence of pesantren[s] in the era can be maintained and focus on reformulation of moral fortress and morality. The reformulation that authors offer is through internalization and adaptation of modern civilization and focus on improvements in educational institutions, both in the economic, socio-cultural, and technological. Keywords: Kyai in Pesantren, Political Dynamics This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons 4.0 Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ©2018 by author and Faculty of education, Universitas Negeri Padang. -

Representation of Political Ideology in Advertising: Semiotics Analysis in Indonesia Television Rizki Briandana

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-3, May - Jun, 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.4.3.31 ISSN: 2456-7620 Representation of Political Ideology in Advertising: Semiotics Analysis in Indonesia Television Rizki Briandana Faculty of Communication Sciene, Universitas Mercu Buana, Jakarta-Indonesia Abstract— This study aims to analyze the meaning and members can come from various provinces, customs, symbols in the political party's advertising on Indonesian backgrounds and beliefs (Ufen, 2008). Therefore the television. Towards the presidential election, political ideology, vision and mission of political parties should be parties use advertising as a means of marketing formed according to the dream or aspiration of the communication. As the form of persuasive information, the Indonesian State and its people. In other words, it can be Perindo Party's television advertisement was analyzed by main motivation and drive for the activities of political using Charles Sanders Pierce's Triangle of Meaning for the parties (Sen & Hill, 2006). Political parties are media or semiotic method. According to Pierce, the signs in the means of citizen participation in fighting for the ideals of picture can be classified into the types of signs in semiotics. the state and society (Gazali, Hidayat, & Menayang, Pierce divides the signs into: icons, indixes and symbols. 2009). For this reason, it is indisputable that political The research results show that Perindo Party's Nationalist parties will be developing. On the other hand, for political ideology upholds pluralism in Indonesia. It has special actors it is an opportunity to establish a new party message that Indonesia does not belong to a particular (Baswedan, 2004). -

The Utilization of Broadcasting Media in Meeting the Information Needs of Prospective Regional Chief Regarding Political News

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Winter 2-27-2021 THE UTILIZATION OF BROADCASTING MEDIA IN MEETING THE INFORMATION NEEDS OF PROSPECTIVE REGIONAL CHIEF REGARDING POLITICAL NEWS Mohammad Zamroni UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta, [email protected] suwandi sumartias Faculty of Communication Sciences, Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia, [email protected] soeganda priyatna Faculty of Communication Sciences, Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia, [email protected] atie rachmiatie Faculty of Communication Sciences, Bandung Islamic University, Indonesia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Television Commons Zamroni, Mohammad; sumartias, suwandi; priyatna, soeganda; and rachmiatie, atie, "THE UTILIZATION OF BROADCASTING MEDIA IN MEETING THE INFORMATION NEEDS OF PROSPECTIVE REGIONAL CHIEF REGARDING POLITICAL NEWS" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5204. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5204 THE UTILIZATION OF BROADCASTING MEDIA IN MEETING THE INFORMATION NEEDS OF PROSPECTIVE REGIONAL CHIEF REGARDING POLITICAL NEWS Mohammad Zamroni Faculty of Communication Science, Padjadjaran University, -

Final Evaluation Report for the Project

Final Evaluation Report For the Project: Countering & Preventing Radicalization in Indonesian Pesantren Submitted to Provided by Lanny Octavia & Esti Wahyuni 7th July 2014 Table of Contents 1. ACRONYM & GLOSSARY 3 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 3. CONTEXT ANALYSIS 7 4. INTRODUCTION 7 5. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY & TOOLS 8 6. EVALUATION FINDING & ANALYSIS 10 6.1 Project’s Relevance 10 6.2 Project’s Effectiveness 20 6.3 Project’s Sustainability 34 7. CONCLUSIONS 37 8. RECOMMENDATIONS 37 9. APPENDICES 39 9.1. Brief Biography of Evaluators 39 9.2. Questionnaire 39 9.3 Focus Group Discussion 49 9.3.1 Students 49 9.3.2 Community Leaders and Members 53 9.4 Key Informant Interview 56 9.4.1 Kiyai/Principal/Teacher 56 9.4.2 Community/Religious Leaders 57 9.5 List of Interviewees 59 9.6 Quantitative Data Results 60 9.6.1 Baseline & Endline Comparison 60 9.6.2 Knowledge on Pesantren’s Community Radio 73 9.6.3 Pesantren’s Radio Listenership 74 9.6.4 Student’s Skill Improvement 75 9.6.5 Number of Pesantren Radio Officers 75 2 | P a g e Acronyms & Glossary Ahmadiya : A minority Muslim sect many conservatives consider heretical, as it refers to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad who claimed that he was the reformer and the promised messiah awaited by Muslims. API : Asrama Perguruan Islam (Islamic Boarding School) Aswaja : Ahlussunnah Waljamaah (people of the tradition of Muhammad and the consensus of the ummah), Sunni Muslims Barongsai : Chinese lion dance Bhinneka Tunggal Ika : United in Diversity CSO : Civil Society Organization EET : External Evaluator Team FGD : Focused Group -

The Indonesian Presidential Election: Now a Real Horse Race?

Asia Pacific Bulletin EastWestCenter.org/APB Number 266 | June 5, 2014 The Indonesian Presidential Election: Now a Real Horse Race? BY ALPHONSE F. LA PORTA The startling about-face of Indonesia’s second largest political party, Golkar, which is also the legacy political movement of deposed President Suharto, to bolt from a coalition with the front-runner Joko Widodo, or “Jokowi,” to team up with the controversial retired general Prabowo Subianto, raises the possibility that the forthcoming July 9 presidential election will be more than a public crowning of the populist Jokowi. Alphonse F. La Porta, former Golkar, Indonesia’s second largest vote-getter in the April 9 parliamentary election, made President of the US-Indonesia its decision on May 19 based on the calculus by party leaders that Golkar’s role in Society, explains that “With government would better be served by joining with a strong figure like Prabowo rather more forthcoming support from than Widodo, who is a neophyte to leadership on the national level. Thus a large coalition of parties fronted by the authoritarian-minded Prabowo will now be pitted against the the top level of the PDI-P, it is smaller coalition of the nationalist Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), which had just possible that Jokowi could selected former vice president Jusuf Kalla, nominally of Golkar, as Jokowi’s running mate. achieve the 44 percent plurality If this turn of events sounds complicated, it is—even for Indonesian politics. But first a look some forecast in the presidential at some of the basics: election, but against Prabowo’s rising 28 percent, the election is Indonesia’s fourth general election since Suharto’s downfall in 1998 has marked another increasingly becoming a real— milestone in Indonesia’s democratization journey.