Final Corrected Diss4-28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecstatic Melancholic: Ambivalence, Electronic Music and Social Change Around the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Ecstatic Melancholic: Ambivalence, Electronic Music and Social Change around the Fall of the Berlin Wall Ben Gook The Cold War’s end infused electronic music in Berlin after 1989 with an ecstatic intensity. Enthused communities came together to live out that energy and experiment in conditions informed by past suffering and hope for the future. This techno-scene became an ‘intimate public’ (Berlant) within an emergent ‘structure of feeling’ (Williams). Techno parties held out a promise of freedom while Germany’s re-unification quickly broke into disputes and mutual suspicion. Tracing the historical movement during the first years of re-unified Germany, this article adds to accounts of ecstasy by considering it in conjunction with melancholy, arguing for an ambivalent description of ecstatic experience – and of emotional life more broadly. Keywords: German re-unification, electronic dance music, structure of feeling, intimate publics, ambivalence. Everybody was happy Ecstasy shining down on me ... I’m raving, I’m raving But do I really feel the way I feel?1 In Germany around 1989, techno music coursed through a population already energised by the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The years 1989 and 1990 were optimistic for many in Germany and elsewhere. The Cold War’s end heralded a conclusion to various deadlocks. Young Germans acutely felt this release from stasis and rushed to the techno-scene.2 Similar scenes also flourished in neighbouring European countries, the United States and Britain around the 1 ‘Raving I’m Raving,’ Shut up and Dance (UK: Shut Up and Dance Records, 1992), vinyl. Funding from the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions Associate Investigator (CE110001011) scheme helped with this work. -

URMC V118n83 20091210.Pdf (9.241Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 118 | No. 8 T D THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 B ASCS ICE, ICE, BABY BOG Leg. a airs director wants student voice on governing board B KIRSTEN SIVEIRA The Rocky ountain Collegian After CSU’s governing board decided to ban concealed weapons on campus, spark- TODAYS IG ing intense controversy student leaders said Wednesday that there must be a student vot- 25 degrees ing member on the board because its mem- bers refuse to listen to students. So far this season, CSU To secure that voting member, Associ- has received a total of 44.2 ated Students of CSU Director of Legislative inches of snow with fi ve full YEAR SEASONA Affairs Matt Worthington drafted a resolu- months of the snow season TOTA IN INCES tion that would allow state leaders to appoint still ahead, according to re- a student to vote on the CSU System Board search from the Department 1 9 9 9 - 2 0 0 0 : 3 . of Governors. The ASCSU Senate moved his of Atmospheric Science. 2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 1 : 5 resolution to committee Wednesday night. Even if the city receives 2 0 0 1 - 2 0 0 2 : 4 4 .1 ASCSU President Dan Gearhart and CSU- no more snow this winter, 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 : 1. Pueblo student government President Steve Fort Collins has already re- 2 0 0 3 - 2 0 0 4 : 9 .1 Titus both currently sit on the BOG as non- ceived more snow than in six 2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 : 5 . -

YASIIN BEY Formerly Known As “Mos Def”

The Apollo Theater and the Kennedy Center Present Final U.S. Performances for Hip-Hop Legend YASIIN BEY Formerly Known as “Mos Def” The Apollo Theater Tuesday, December 21st, 2016 The Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Celebration at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall Saturday, December 31st, 2016 – Monday, January 2, 2017 (Harlem, NY) – The Apollo Theater and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced today that they will present the final U.S. performances of one of hip hop’s most influential artists - Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def). These special engagements follow Bey’s announcement earlier this year of his retirement from the music business and will kick-off at the Apollo Theater on Tuesday, December 21st, culminating at The Kennedy Center from Saturday, December 31st through Sunday, January 2, 2017. Every show will offer a unique musical experience for audiences with Bey performing songs from a different album each night including The New Danger, True Magic, The Ecstatic, and Black on Both Sides, alongside new material. He will also be joined by surprise special guests for each performance. Additionally, The Kennedy Center shows will serve as a New Years Eve celebration and will feature a post-show party in the Grand Foyer. Yasin Bey has appeared at both the Apollo Theater and Kennedy Center multiple times throughout his career. “We are so excited to collaborate with the Kennedy Center on what will be a milestone moment in not only hip-hop history but also in popular culture. The Apollo is the epicenter of African American culture and has always been a nurturer and supporter of innovation and artistic brilliance, so it is only fitting that Yasiin Bey have his final U.S. -

The Spirit of Dancehall: Embodying a New Nomos in Jamaica Khytie K

The Spirit of Dancehall: embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 17-31 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/686008 Access provided by Harvard University (20 Feb 2018 17:21 GMT) The Spirit of Dancehall embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown As we approached the vicinity of the tent we heard the wailing voices, dominated by church women, singing old Jamaican spirituals. The heart beat riddim of the drums pulsed and reverberated, giving life to the chorus. “Alleluia!” “Praise God!” Indecipherable glossolalia punctu- ated the emphatic praise. The sounds were foreboding. Even at eleven years old, I held firmly to the disciplining of my body that my Catholic primary school so carefully cultivated. As people around me praised God and yelled obscenely in unknown tongues, giving their bodies over to the spirit in ecstatic dancing, marching, and rolling, it was imperative that I remained in control of my body. What if I too was suddenly overtaken by the spirit? It was par- ticularly disconcerting as I was not con- It was imperative that vinced that there was a qualitative difference between being “inna di spirit I remained in control [of God]” and possessed by other kinds of my body. What if of spirits. I too was suddenly In another ritual space, in the open air, lacking the shelter of a tent, heavy overtaken by the spirit? bass booms from sound boxes. The seis- mic tremors radiate from the center and can be felt early into the Kingston morning. -

Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

encounters ecstatic encounters ecstatic ecstatic encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Ecstatic Encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Layout: Maedium, Utrecht ISBN 978 90 8964 298 1 e-ISBN 978 90 4851 396 3 NUR 761 © Mattijs van de Port / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents PREFACE / 7 INTRODUCTION: Avenida Oceânica / 11 Candomblé, mystery and the-rest-of-what-is in processes of world-making 1 On Immersion / 47 Academics and the seductions of a baroque society 2 Mysteries are Invisible / 69 Understanding images in the Bahia of Dr Raimundo Nina Rodrigues 3 Re-encoding the Primitive / 99 Surrealist appreciations of Candomblé in a violence-ridden world 4 Abstracting Candomblé / 127 Defining the ‘public’ and the ‘particular’ dimensions of a spirit possession cult 5 Allegorical Worlds / 159 Baroque aesthetics and the notion of an ‘absent truth’ 6 Bafflement Politics / 183 Possessions, apparitions and the really real of Candomblé’s miracle productions 5 7 The Permeable Boundary / 215 Media imaginaries in Candomblé’s public performance of authenticity CONCLUSIONS Cracks in the Wall / 249 Invocations of the-rest-of-what-is in the anthropological study of world-making NOTES / 263 BIBLIOGRAPHY / 273 INDEX / 295 ECSTATIC ENCOUNTERS · 6 Preface Oh! Bahia da magia, dos feitiços e da fé. -

Yasiin Bey Formerly Known As “Mos Def”

**ANNOUNCEMENT** The Apollo Theater Announces a Second Show For yasiin bey Formerly Known as “Mos Def” Performances Are Among the Legendary Emcee’s Final US Shows The Apollo Theater Additional Date: Thursday, December 22nd, 2016 (Harlem, NY) – Due to popular demand, the Apollo Theater announced today that it has added a second show on Thursday, December 22nd for yasiin bey (formerly known as Mos Def), one of hip hop’s most influential artists. These special engagements follow bey’s announcement earlier this year of his retirement from the music business and will kick-off at the Apollo Theater on Wednesday, December 21st. Every show will offer a unique musical experience for audiences with bey performing songs from a different album each night including The New Danger, True Magic, The Ecstatic, and Black on Both Sides, alongside new material. He will also be joined by surprise special guests for each performance. Yasiin bey has appeared at the Apollo Theater multiple times throughout his career. Following his final U.S. performances, bey will venture to Africa to focus on his arts, culture, and lifestyle collective A Country Called Earth (ACCE). He will also continue to pursue his newly formed passions as a painter and his art, as well as that of various other ACCE artists, will be anonymously displayed at the Apollo Theater and the Kennedy Center. TICKET INFORMATION Tickets for the second show of yasiin bey at the Apollo go on sale to the public on Thursday, December 15th at 12 Noon. An online ticket pre-sale will be offered to the Apollo’s “A-list” email list beginning Wednesday, December 14th at 12 Noon. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 2-25-2000 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2000). The George-Anne. 1640. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1640 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■H^MH ^^^^H^^H f a u J i h fi : 0 The Official Student Newspaper of Georgia Southern University ;.-,.•:. er' has it all: drops two to humor, wit and Alabama seriousness Charles Harper Webb gives us Eagles lose both games on poetry that is both poignant and the road 12-4 and 9-3 beautiful. during the week. Page 4 Page 6 Vol. 72 No. 61 Friday, February 25, 2000 Want to m Investors aren't the only ones who on it By Kathy Bourassa Don'tThe product was only available to people who Staff Writer agreed to sell the balls. For a little over a hundred their money. Valentine points out As you sort your mail an envelope catches your dollars, investors received two laundry balls, adver- banks have collapsed in the U.S. attention. There is no return address but the postmark tising pamphlets, and an explanation of the "pay- abroad, leaving customers hold- indicates that it originated from another state. -

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 664. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr. -

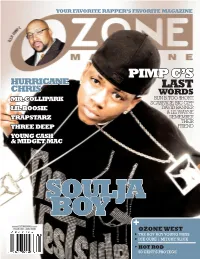

PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR

OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR. COLLIPARK BUN B, TOO $HORT, SCARFACE, BIG GIPP LIL BOOSIE DAVID BANNER & LIL WAYNE REMEMBER TRILL N*GGAS DON’T DIE DON’T N*GGAS TRILL TRAPSTARZ THEIR THREE DEEP FRIEND YOUNG CASH & MIDGET MAC SOULJA BOY +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS JANUARY 2008 ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S LAST WORDS SOULJA BUN B BOY TOO $HORT CRANKIN’ IT SCARFACE ALL THE WAY BIG GIPP TO THE BANK WITH DAVID BANNER MR. COLLIPARK LIL WAYNE FONSWORTH LIL BOOSIE’S BENTLEY JEWELRY CORY MO 8BALL & FASCINATION MORE TRAPSTARZ SHARE THEIR THREE DEEP FAVORITE MEMORIES OF THE YOUNG CASH SOUTH’S & MIDGET MAC FINEST HURRICANE CHRIS +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden features ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson 54-59 YEAR END AWARDS PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 76-79 REMEMBERING PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 22-23 RAPPERS’ NEW YEARS RESOLUTIONS LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 74 DIRTY THIRTY: PIMP C’S GREATEST HITS SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

DIAMONDS & MUSIC I

$6.99 (U.S.), $3.39 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw N W Z : -DIGIT 908 Illllllllllll llllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllll I B1240804 APROE A04 E0101 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE N A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNAT ON4L AUTHORITY ON ML SIC, VIDEO AND DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 21, 20C4 LUXU Q\Y" E É DIAMONDS & MUSIC i SPE(IAL REPORT INSIDE i www.americanradiohistory.com HOW ABOUT YOU BLINDING THE PAPARAZZI FOR A CHANGE A DIAMOND IS FOREVER ¡ THE FOREVERMPRK IS USED UNDER LICENSE. WWW.P DIA MIONDIS FOREVER.COM www.americanradiohistory.com $6.99 (U.S.), $8.99 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw a `) zW Iong Specia eport Begins On Page 19 www.billboard.com THE INTERNATIONAL AUTHORITY ON MUSIC, VIDEO AND DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT 110TH YEARra AUGUST 21, 2004 HOT SPOTS Battling To Save Archives At Risk BY BILL HOLLAND When it comes to recorded music archives, there ain't nothing like the real thing. As technology evolves, it is essential, archivists say, that re- issues on new audio platforms be based on original masters. Unfortunately, in an unexpected by- product of digital - era recording, many original masters are in danger of dete- riorating or becoming obsolete. 13 A Bright Remedy That's because the material was This is a first in a Meredith Brooks' 2002 single recorded on early digital equipment two -part series on the challenges `Shine' re- emerges as the that is no longer manufactured. In U.S. record new song `The Dr. -

The Beacon, November 2, 2006 Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) Special Collections and University Archives 11-2-2006 The Beacon, November 2, 2006 Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Florida International University, "The Beacon, November 2, 2006" (2006). The Panther Press (formerly The Beacon). 41. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper/41 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 38 3 A Forum for Free Student Expression at Florida International University Vol. 19, Issue 26 www.beaconnewspaper.com November 2, 2006 BBC students report ‘peeping tom’ incidents CRISTELA GUERRA and just stared me down.” cropped hair watched her. It was around 4 in journalism, remembers discussing the BBC Managing Editor Novoa isn’t alone in her experience. p.m. when she entered the restroom across incident with Costa after it occurred. She The past few months have found a from the Honor’s College in AC I. later came into contact with a black male Vanessa Novoa left her class at 7:20 p.m. ‘peeping tom’ alienating female students “Something caught my attention from who resembled the suspect walking out of in Biscayne Bay’s Academic I building to on campus and peaking in on them as they the corner of my eye, and I saw something the same bathroom.