Ecstatic Melancholic: Ambivalence, Electronic Music and Social Change Around the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shame and Philosophy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Philosophy Papers and Journal Articles School of Philosophy 2010 Shame and philosophy Richard P. Hamilton University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/phil_article Part of the Philosophy Commons This book review in a scholarly journal was originally published as: Hamilton, R. P. (2010). Shame and philosophy. Res Publica, 16 (4), 431-439. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-010-9120-4 This book review in a scholarly journal is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/ phil_article/14. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Res Publica DOI 10.1007/s11158-010-9120-4 12 3 Shaming Philosophy 4 Richard Paul Hamilton 5 6 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 7 8 Michael L. Morgan (2008), On Shame. London: RoutledgePROOF (Thinking In Action). 9 Philip Hutchinson (2008), Philosophy and Shame: An Investigation in the 10 Philosophy of Emotions and Ethics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 11 Shame is a ubiquitous and highly intriguing feature of human experience. It can 12 motivate but it can also paralyse. It is something which one can legitimately demand 13 of another, but is not usually experienced as a choice. Perpetrators of atrocities can 14 remain defiantly immune to shame while their victims are racked by it. It would be 15 hard to understand any society or culture without understanding the characteristic 16 occasions upon which shame is expected and where it is mitigated. Yet, one can 17 survey much of the literature in social and political theory over the last century and 18 find barely a footnote to this omnipresent emotional experience. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses 'Head-hunting' (or grief management) on Teesside: Pregnancy loss and the use of counselling as a ritual in the resolution of consequential grief Brydon, Christine How to cite: Brydon, Christine (2001) 'Head-hunting' (or grief management) on Teesside: Pregnancy loss and the use of counselling as a ritual in the resolution of consequential grief, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4209/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Christine Brydon 'Head-Hunting' (or Grief Management) on Teesside Pregnancy Loss and the Use of Counselling as a Ritual in the Resolution of Consequential Grief. Master of Arts Degree by Thesis University of Durham Department of Anthropology 2001 Abstract This anthropological thesis is based on an evaluation carried out at South Cleveland Hospital on Teesside, where midwives offer counselling to bereaved parents following pregnancy loss. -

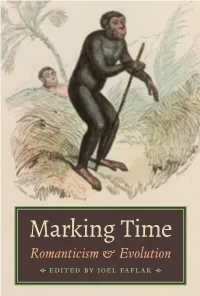

Faflak 5379 6208 0448F Final Pass.Indd

Marking Time Romanticism & Evolution EditEd by JoEl FaFlak MARKING TIME Romanticism and Evolution EDITED BY JOEL FAFLAK Marking Time Romanticism and Evolution UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2017 Toronto Buffalo London www.utorontopress.com ISBN 978-1-4426-4430-4 (cloth) Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Marking time : Romanticism and evolution / edited by Joel Faflak. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4430-4 (hardcover) 1. Romanticism. 2. Evolution (Biology) in literature. 3. Literature and science. I. Faflak, Joel, 1959–, editor PN603.M37 2017 809'.933609034 C2017-905010-9 CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Tor onto Press. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. Funded by the Financé par le Government gouvernement of Canada du Canada Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction – Marking Time: Romanticism and Evolution 3 joel faflak Part One: Romanticism’s Darwin 1 Plants, Analogy, and Perfection: Loose and Strict Analogies 29 gillian beer 2 Darwin and the Mobility of Species 45 alan bewell 3 Darwin’s Ideas 68 matthew rowlinson Part Two: Romantic Temporalities 4 Deep Time in the South Pacifi c: Scientifi c Voyaging and the Ancient/Primitive Analogy 95 noah heringman 5 Malthus Our Contemporary? Toward a Political Economy of Sex 122 maureen n. -

Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900 Nicole Zeftel The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2613 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SICKLY SENTIMENTALISM: SYMPATHY AND PATHOLOGY IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE, 1866-1900 by NICOLE ZEFTEL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 NICOLE ZEFTEL All Rights Reserved ! ii! Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date ! Hildegard Hoeller Chair of Examining Committee Date ! Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Eric Lott Bettina Lerner THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ! iii! ABSTRACT Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel Advisors: Hildegard Hoeller and Eric Lott Sickly Sentimentalism: Pathology and Sympathy in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 examines the work of four American women novelists writing between 1866 and 1900 as responses to a dominant medical discourse that pathologized women’s emotions. -

On Mourning Sickness

Missed Revolutions, Non-Revolutions, Revolutions to Come: On Mourning Sickness An Encounter with: Rebecca Comay. Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. 224 pages. REBECCA COMAY in Conversation with JOSHUA NICHOLS Rebecca Comay’s new book Mourning Sickness sets its sights on Hegel’s response to the French Revolutionary Terror. In this respect it provides the reader with both a detailed examination of Hegel’s interpretation of the Terror and the historical and philosophical context of this interpretation. In and of itself this would be a valuable contribution to the history of philosophy in general and Hegel studies in particular, but Comay’s book extends beyond the confines of a historical study. It explores Hegel’s struggle with the meaning of the Terror and, as such, it explores the general relationship between event and meaning. By doing so this book forcefully draws Hegel into present-day discussions of politics, violence, trauma, witness, and memory. The following interview took place via email correspondence. The overall aim is twofold: to introduce the main themes of the book and to touch on some of its contemporary implications. JOSHUA NICHOLS: This text accomplishes the rare feat of revisiting what is, in many respects, familiar and well-worn philosophical terrain (i.e., Hegel’s Phenomenology) and brings the reader to see the text from a new angle, under a different light, almost as if for the first time. PhaenEx 7, no. 1 (spring/summer 2012): 309-346 © 2012 Rebecca Comay and Joshua Nichols - 310 - PhaenEx Your reading of Hegel’s notion of forgiveness as being “as hyperbolic as anything in Derrida, as asymmetrical as anything in Levinas, as disastrous as anything in Blanchot, as paradoxical as anything in Kierkegaard” is just one example of the surprising interpretive possibilities that this text opens (Comay, Mourning Sickness 135). -

Dark Tourism

Dark Tourism: Understanding the Concept and Recognizing the Values Ramesh Raj Kunwar, PhD APF Command and Staff College, Nepal Email: [email protected] Neeru Karki Department of Conflict, Peace and Development Studies, TU Email: [email protected] „Man stands in his own shadow and wonders why it‟s dark‟ (Zen Proverb; in Stone, Hartmann, Seaton, Sharpley & White, 2018, preface). Abstract Dark tourism is a youngest subset of tourism, introduced only in 1990s. It is a multifaceted and diverse phenomenon. Dark tourism studies carried out in the Western countries succinctly portrays dark tourism as a study of history and heritage, tourism and tragedies. Dark tourism has been identified as niche or special interest tourism. This paper highlights how dark tourism has been theoretically conceptualized in previous studies. As an umbrella concept dark tourism includes than tourism, blackspot tourism, morbid tourism, disaster tourism, conflict tourism, dissonant heritage tourism and others. This paper examines how dark tourism as a distinct form of tourism came into existence in the tourism academia and how it could be understood as a separate subset of tourism in better way. Basically, this study focuses on deathscapes, repressed sadism, commercialization of grief, commoditization of death, dartainment, blackpackers, darsumers and deathseekers capitalism. This study generates curiosity among the readers and researchers to understand and explore the concepts and values of dark tourism in a better way. Keywords: Dark tourism, authenticity, supply and demand, emotion and experience Introduction Tourism is a complex phenomenon involving a wide range of people, increasingly seeking for new and unique experiences in order to satisfy the most diverse motives, reason why the world tourism landscape has been changing in the last decades (Seabra, Abrantes, & Karstenholz, 2014; in Fonseca, Seabra, & Silva, 2016, p. -

Negotiating Agendas, Ethics, and Consequences Regarding the Heritage Value of Human Remains

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2016 A Conflict of Interest? Negotiating Agendas, Ethics, and Consequences Regarding the Heritage Value of Human Remains Heidi J. Bauer-Clapp University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bauer-Clapp, Heidi J., "A Conflict of Interest? Negotiating Agendas, Ethics, and Consequences Regarding the Heritage Value of Human Remains" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 643. https://doi.org/10.7275/8431228.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/643 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONFLICT OF INTEREST? NEGOTIATING AGENDAS, ETHICS, AND CONSEQUENCES REGARDING THE HERITAGE VALUE OF HUMAN REMAINS A Dissertation Presented by HEIDI J. BAUER-CLAPP Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2016 Anthropology © Copyright by Heidi J. Bauer-Clapp 2016 All Rights Reserved A CONFLICT OF INTEREST? NEGOTIATING AGENDAS, ETHICS, AND CONSEQUENCES REGARDING THE HERITAGE VALUE OF HUMAN REMAINS -

YASIIN BEY Formerly Known As “Mos Def”

The Apollo Theater and the Kennedy Center Present Final U.S. Performances for Hip-Hop Legend YASIIN BEY Formerly Known as “Mos Def” The Apollo Theater Tuesday, December 21st, 2016 The Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Celebration at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall Saturday, December 31st, 2016 – Monday, January 2, 2017 (Harlem, NY) – The Apollo Theater and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced today that they will present the final U.S. performances of one of hip hop’s most influential artists - Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def). These special engagements follow Bey’s announcement earlier this year of his retirement from the music business and will kick-off at the Apollo Theater on Tuesday, December 21st, culminating at The Kennedy Center from Saturday, December 31st through Sunday, January 2, 2017. Every show will offer a unique musical experience for audiences with Bey performing songs from a different album each night including The New Danger, True Magic, The Ecstatic, and Black on Both Sides, alongside new material. He will also be joined by surprise special guests for each performance. Additionally, The Kennedy Center shows will serve as a New Years Eve celebration and will feature a post-show party in the Grand Foyer. Yasin Bey has appeared at both the Apollo Theater and Kennedy Center multiple times throughout his career. “We are so excited to collaborate with the Kennedy Center on what will be a milestone moment in not only hip-hop history but also in popular culture. The Apollo is the epicenter of African American culture and has always been a nurturer and supporter of innovation and artistic brilliance, so it is only fitting that Yasiin Bey have his final U.S. -

The Spirit of Dancehall: Embodying a New Nomos in Jamaica Khytie K

The Spirit of Dancehall: embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 17-31 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/686008 Access provided by Harvard University (20 Feb 2018 17:21 GMT) The Spirit of Dancehall embodying a new nomos in Jamaica Khytie K. Brown As we approached the vicinity of the tent we heard the wailing voices, dominated by church women, singing old Jamaican spirituals. The heart beat riddim of the drums pulsed and reverberated, giving life to the chorus. “Alleluia!” “Praise God!” Indecipherable glossolalia punctu- ated the emphatic praise. The sounds were foreboding. Even at eleven years old, I held firmly to the disciplining of my body that my Catholic primary school so carefully cultivated. As people around me praised God and yelled obscenely in unknown tongues, giving their bodies over to the spirit in ecstatic dancing, marching, and rolling, it was imperative that I remained in control of my body. What if I too was suddenly overtaken by the spirit? It was par- ticularly disconcerting as I was not con- It was imperative that vinced that there was a qualitative difference between being “inna di spirit I remained in control [of God]” and possessed by other kinds of my body. What if of spirits. I too was suddenly In another ritual space, in the open air, lacking the shelter of a tent, heavy overtaken by the spirit? bass booms from sound boxes. The seis- mic tremors radiate from the center and can be felt early into the Kingston morning. -

Prototype Theory and Emotion Semantic Change Aotao Xu ([email protected]) Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto

Prototype theory and emotion semantic change Aotao Xu ([email protected]) Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto Jennifer Stellar ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, University of Toronto Yang Xu ([email protected]) Department of Computer Science, Cognitive Science Program, University of Toronto Abstract provided evidence for this prototype view using a variety An elaborate repertoire of emotions is one feature that dis- of stimuli ranging from emotion words (Storm & Storm, tinguishes humans from animals. Language offers a critical 1987), videos (Cowen & Keltner, 2017), and facial expres- form of emotion expression. However, it is unclear whether sions (Russell & Bullock, 1986; Ekman, 1992). Prototype the meaning of an emotion word remains stable, and what fac- tors may underlie changes in emotion meaning. We hypothe- theory provides a synchronic account of the mental represen- size that emotion word meanings have changed over time and tation of emotion terms, but how this view extends or relates that the prototypicality of an emotion term drives this change to the diachronic development of emotion words is an open beyond general factors such as word frequency. We develop a vector-space representation of emotion and show that this problem that forms the basis of our inquiry. model replicates empirical findings on prototypicality judg- ments and basic categories of emotion. We provide evidence Theories of semantic change that more prototypical emotion words have undergone less change in meaning than peripheral emotion words over the past Our work also draws on an independent line of research in century, and that this trend holds within each family of emo- historical semantic change. -

Nolan Washington 0250O 19397

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of University of Washington Committee: Program Authorized to Offer Degree: ©Copyright 2018 Daniel A. Nolan IV University of Washington Abstract Souvenirs and Travel Guides: The Cognitive Sociology of Grieving Public Figures Daniel A. Nolan IV Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sarah Quinn Department of Sociology The deaths of public figures can produce a variety of emotional reactions. While bereavement research has explored mourning family or close friends, this literature does little to address the experience of grief for public figures. Similarly, research on how people relate to public figures provides an incomplete picture of the symbolic associations people can form with those figures. This study relies on interviews with individuals who had a memorable reaction to the death of a public figure to explore how these individuals related to that figure. Results suggest two ideal type reactions: Grief, characterized by disruption and sharp pain, and Melancholy, characterized by distraction and dull ache. Respondents reported symbolic associations between the figure and some meaning they had incorporated into their cognitive framework. I argue that emotional reactions to the death of a public figure are an affective signal of disruption to the individual’s cognitive functioning caused by the loss of meaning maintained by the figure. The key difference in kind and intensity of reaction is related to the cognitive salience of the lost meaning. This research highlights how individuals use internalized cultural objects in their sense-making process. More broadly, by revealing symbolically meaningful relationships that shape cognitive frameworks, this analysis offers cognitive sociological insights into research about the function of role models, collective memories, and other cultural objects on the individual’s understanding of their world. -

Final Corrected Diss4-28

21ST CENTURY MOJO: THE PRACTICE OF RITUAL AND HIP HOP AMONG BRIGHT, BLACK UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AT A PREDOMINANTLY WHITE UNIVERSITY by J. SEAN CALLAHAN (Under the direction of Tarek C. Grantham and Elizabeth A. St. Pierre) ABSTRACT In this qualitative project, I interviewed eight Black male and female students, ages 22-30, to explore how they engage hip hop culture within the social, cultural, political, and historical conditions specific to the southeastern flagship university they attend. By focusing on their everyday lives and the interactions that are possible within the multiple social spaces of the university, my purpose was to better understand how these students use hip hop culture to make sense of their experiences on campus. More specifically, my dissertation locates the ritual practices that these students perform in the process of constructing and negotiating the socio-cultural terrain of the university; addresses the methodological issues that arise when conducting qualitative research that focuses on gifted, Black students; and explores the educative value of practicing hip hop. The significance of this work lies with its attention to the intersection where the processes of cultural production meet giftedness as well as its emphasis on the socio-emotional development of gifted and talented Black university students. INDEX WORDS: Interdisciplinary research, Hip hop, Culture, Gifted black students, Qualitative research, Ethnography, Gifted education, Curriculum, Performativity, Conjure, Rituals, Spirituality, Identity, Socio- emotional development 21ST CENTURY MOJO: THE PRACTICE OF RITUAL AND HIP HOP AMONG BRIGHT, BLACK UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AT A PREDOMINANTLY WHITE UNIVERSITY by J. SEAN CALLAHAN B.A., University of West Georgia, 1998 M.Ed., University of Georgia, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2012 © 2012 J.