Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SEED THIEF by Jacqui L'ange Submissioncorrect

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University The Seed Thief Jacqui L’Ange LNGJAC001 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing Town Faculty of the HumanitiesCape Universityof of Cape Town 2012 COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has notUniversity been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: Town Cape of University Abstract At face value, The Seed Thief is a contemporary quest story. Maddy Bellani, a botanist with the Millennium Seed Bank in Cape Town, is sent on the trail of an African plant thought to be extinct on the continent, and believed to be growing in Brazil. Maddy is a reluctant heroine, a botanist of many places but no home, who responds to the call because she believes it might help her put some of her unsettledness to rest. But when she finds herself in a place that shakes her preconceptions to the core, the myths she has constructed to prop up her life and sense of self come crashing down around her. -

Robert GADEN: Slim GAILLARD

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Robert GADEN: Robert Gaden -v,ldr; H.O. McFarlane, Karl Emmerling, Karl Nierenz -tp; Eduard Krause, Paul Hartmann -tb; Kurt Arlt, Joe Alex, Wolf Gradies -ts,as,bs; Hans Becker, Alex Beregowsky, Adalbert Luczkowski -v; Horst Kudritzki -p; Harold M. Kirchstein -g; Karl Grassnick -tu,b; Waldi Luczkowski - d; recorded September 1933 in Berlin 65485 ORIENT EXPRESS 2.47 EOD1717-2 Elec EG2859 Robert Gaden und sein Orchester; recorded September 16, 1933 in Berlin 108044 ORIENTEXPRESS 2.45 OD1717-2 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded December 1936 in Berlin 105298 MEIN ENTZÜCKENDES FRÄULEIN 2.21 ORA 1653-1 HMV EG3821 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded October 1938 in Berlin 106900 ICH HAB DAS GLÜCK GESEHEN 2.12 ORA3296-2 Elec EG6519 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded November 1938 in Berlin 106902 SIGNORINA 2.40 ORA3571-2 Elec EG6567 106962 SPANISCHER ZIGEUNERTANZ 2.45 ORA 3370-1 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; Refraingesang: Rudi Schuricke; recorded September 1939 in Berlin 106907 TAUSEND SCHÖNE MÄRCHEN 2.56 ORA4169-1 Elec EG7098 ------------------------------------------ Slim GAILLARD: "Swing Street" Slim Gaillard -g,vib,vo; Slam Stewart -b; Sam Allen -p; Pompey 'Guts' Dobson -d; recorded February 17, 1938 in New York 9079 FLAT FOOT FLOOGIE 2.51 22318-4 Voc 4021 Some sources say that Lionel Hampton plays vibraphone. 98874 CHINATOWN MY CHINATOWN -

Universality and Diversity in Human Song Samuel A. Mehr1,2*, Manvir

This is a provisionally accepted manuscript. The published version will differ from it substantially. Please cite it as: Mehr, S. A., Singh, M., Knox, D., Ketter, D. M., Pickens-Jones, D., Atwood, S., Lucas, C., Egner, A., Jacoby, N., Hopkins, E. J., Howard, R. M., Hartshorne, J. K., Jennings, M. V., Simson, J., Bainbridge, C. M., Pinker, S., O'Donnell, T. J., Krasnow, M. M., & Glowacki, L. (forthcoming). Universality and diversity in human song. Science . Universality and diversity in human song Samuel A. Mehr 1,2*, Manvir Singh 3*, Dean Knox 4, Daniel M. Ketter 6,7, Daniel Pickens-Jones 8, Stephanie Atwood 2, Christopher Lucas 5, Alena Egner 2, Nori Jacoby 10, Erin J. Hopkins 2, Rhea M. Howard 2, Timothy J. O’Donnell 11, Steven Pinker 2, Max M. Krasnow 2, and Luke Glowacki 12* 1 Data Science Initiative, Harvard University 2 Department of Psychology, Harvard University 3 Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University 4 Department of Politics, Princeton University 5 Department of Political Science, Washington University in St. Louis 6 Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester 7 Department of Music, Missouri State University 8 Portland, Oregon 9 Department of Psychology, University of California at Los Angeles 10 Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics 11 Department of Linguistics, McGill University 12 Department of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University *Correspondence to [email protected] (S.A.M.), [email protected] (M.S.), and [email protected] (L.G.) Abstract What is universal about music across human societies, and what varies? We built a corpus of ethnographic text on musical behavior from a representative sample of the world’s societies and a discography of audio recordings of the music itself. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Copyright by Daniel Sherwood Sotelino 2006 Choro Paulistano and the Seven-String Guitar: an Ethnographic History

Copyright by Daniel Sherwood Sotelino 2006 Choro Paulistano and the Seven-String Guitar: an Ethnographic History by Daniel Sherwood Sotelino, B.A. Master’s Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Ethnomusicology Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May 2006 Choro Paulistano and the Seven-String Guitar: an Ethnographic History Approved by Supervising Committee: Dedication To Dr. Gerard Béhague Friend and Mentor Treasure of Knowledge 1937–2005 Acknowledgements I would like to express utmost gratitude to my family–my wife, Mariah, my brother, Marco, and my parents, Fernando & Karen–for supporting my musical and scholarly pursuits for all of these years. I offer special thanks to José Luiz Herencia and the Instituto Moreira Salles, luthier João Batista, the great chorões Israel and Izaías Bueno de Almeida, Luizinho Sete Cordas, Arnaldinho at Contemporânea Instrumentos Musicais, Sandra at the Music Library of UFRJ, Wilson Sete Cordas, the folks at Ó do Borogodó, and everyone at Praça Benedito Calixto, Sesc Pompéia, Pop’s Music, and Cachuera. I am very appreciative of Lúcia for all of her delicious cooking. I am fortunate to have worked with the professors and instructors at the University of Texas-Austin: Dr. Slawek, my advisor, who truly encourages intellectual exploration; Dr. Moore for his candid observations; Dr. Hale for his tireless dedication to teaching; Dr. Mooney, for wonderful research opportunities; Dr. Dell’Antonio for looking out for the interests and needs of students, and for providing valuable insight; Dr. -

Elkin, Judith Laikin. "Jews and Non-Jews. " the Jews of Latin America. Rev. Ed. New York

THE JEWS OF LATIN AMERICA Revised Edition JUDITH LAIKIN ELKIN HOLMES & MEIER NEW YORK / LONDON Published in the United Stutes of America 1998 b y ll olmes & Meier Publishers. Inc . 160 Broadway ew York, NY 10038 Copyr ight © 199 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1.nc. F'irst edition published und er th e title Jeics of the u1tl11A111erica11 lle1'11hlics copyright © 1980 The University of o rth Ca rolina Press . Chapel Hill , NC . All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any elec troni c o r mechanical means now known or to be invented, including photocopying , r co rdin g, and information storage and retrieval systems , without permission in writing from the publishers , exc·ept by a reviewe r who may quote brief passages in a review. The auth or acknow ledges with gra titud e the court esy of the American Jewish lli stori cal Society to reprint the follo,ving articl e which is published in somewhat different form in this book: "Goo dnight , Sweet Gaucho: A Revisio nist View of the Jewis h Agricultural Experiment in Argentina, " A111eric1111j etds h Historic(I/ Q11111terly67 (March 1978 ): 208 - 23. Most of the photographs in this boo k were includ d in the exhibit ion . "Voyages to F're dam: .500 Years of Je,vish Li~ in Latin America and the Caribbean ," and were ma de availab le throu ,I, the court esy of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith . Th e two photographs of the AMIA on pages 266 - 267 we re s uppli ed by the AMIA -Co munidad Judfa de Buenos Aires. -

Inter-American Development Bank

SIMULTANEOUS DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT OF THE INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK BRAZIL NATIONAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM IN BAHIA (PRODETUR NACIONAL-BAHIA) (BR-L1300) LOAN PROPOSAL This document was prepared by the project team consisting of: Adela Moreda (INE/RND) and Annette Killmer (RND/CBR), Project Team Co-leaders; Joseph Milewski (RND/CBR); Leonardo Corral (SPD/SDV); Andrés Consuegra (LEG/SGO); Fernando Glasman (FMP/CBR); Carlos Lago (FMP/CBR); Suzanne Casolaro (VPS/ESG); Denise Levy (VPS/ESG); Matias Bendersky (ORP/ORP); Fernanda Soares (ORP/ORP); and Rosario Gaggero (INE/RND). This document is being released to the public and distributed to the Bank’s Board of Executive Directors simultaneously. The Board may or may not approve the document, or may approve it with modifications. If the document is subsequently updated, the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s Access to Information Policy. CONTENTS PROJECT SUMMARY I. DESCRIPTION AND RESULTS MONITORING ..................................................................... 1 A. Background, problems to be addressed, and rationale ......................................... 1 B. Objectives, components, and cost ......................................................................... 8 C. Key results indicators ............................................................................................ 9 II. FINANCING STRUCTURE AND MAIN RISKS ....................................................................10 A. Financing instruments .........................................................................................10 -

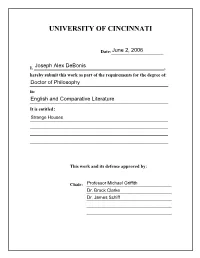

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Strange Houses A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 by Joseph Alex DeBonis B.A. Indiana University, 1996 M.A. Illinois State University, 2001 Committee Chair: Professor Michael Griffith Joseph Alex DeBonis Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, Strange Houses, is a collection of original short stories by the author, Joseph Alex DeBonis. The stories engage notions about home, family, estrangement, and alienation. Since many of the stories deal with family and marital relations, homes feature prominently in the action and as settings. Often characters are estranged or exiled, and their obsessions with having normal families and/or stable lives drive them to construct elaborate fantasies in which they are included, loved, and part of something enduring that is larger than themselves. The dissertation also includes a critical paper, “A Butterfly, a Cannonball, and a Sneeze: Notions of Chaos Theory in Cormac McCarthy’s All The Pretty Horses and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49.” In this essay, I argue that the novel All The Pretty Horses grapples with a sense of freedom that is rife with ambiguity and demonstrates McCarthy’s engagement with chaos theory. -

Fuelwood • In· Colonial Brazil

. ' Fuelwood •in· Colonial Brazil The Economkand Social Consequences of Fuel Depletion for the Bah ian RecOnc:avo,l 549-1820 . Shawn'W. Miller mong the various tasks that con contributed to the contest, in which all eyes of the early Portuguese, the fuel stituted the daily routine of . .colonists participated, for one crucial capacity of the Brazilian forest was ABrazil's sugar economy, col natural resource: wood. · boundless. · lecting fuel from the colony's plentiful Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish forests was among the most extensive. Discovery of the Forest explorers, the people who initiated In addition to preparing land for the expansion of Europe, carrie from planting, cutting cane at harvest, and At the height of the Bahian sugar an environment that had long been refining it ar.rhe mill, African slaves harvest, a view from the bluffs of the stripped of its trees. In fact the entire through four centuries had the addi Bay of All Saints contained a great Mediterranean seaboard, except a · tional burden of gathering the crucial deal of smoke, for all along the north~ few isolated and coveted pockets, energy source that fuelled the sugar ern shoreline, to a few kilometers had been bereft of forests for centu~ mill. This article is in part a study of inland, a considerable array of fires ries. Growing populations and the • - that resource's depletion and of sugar pushed arching columns into the pre growing material demands for ships of vailing southeasterly winds. The :-"- production's detrimental effect on discovery, war, and trade continued N - Brazil's Atlantic forest. -

Comparativ Heft 2-Neu2018.Indd

Jorge Amado’s Salvador da Bahia: Transcultural Place-Making and the Search for “Brazilianness” Martina Kopf ABSTRACTS Der Beitrag untersucht den Entwurf eines transkulturellen Orts und die damit verknüpfte Su- che nach brasilianischer Identität in Jorge Amados (1912–2001) Werk. Amados bevorzugter Schauplatz ist der brasilianische Bundesstaat Bahia, der für seine kulturellen Verbindungen zu Afrika und seine afrobrasilianische Bevölkerung bekannt ist. In Amados Roman Tenda dos mi- lagres (Werkstatt der Wunder) (1968) wird Bahias Hauptstadt Salvador zu einem Ort, an dem kulturelle Einfüsse afrikanischer, brasilianischer und europäischer Herkunft aufeinandertrefen. Mittelpunkt des Romans ist das historische Zentrum von Salvador da Bahia, auch bekannt als Pelourinho, den Amado mit einer Art afrobrasilianischer „Universität“ vergleicht. Der Pelourinho wird so zu einem Ort, an dem brasilianische Kultur als transkulturelle Kultur entsteht, praktiziert und erfahrbar wird. Indem Amado Salvador da Bahia als „Wiege brasilianischer Kultur“ be- und damit brasilianischer Kultur einen konkreten Ort zu-schreibt, leistet er einen Beitrag zur Defniti- on brasilianischer Identität sowohl in einem nationalen als auch einem kulturellen Rahmen. Die Suche nach einer brasilianischen Identität bedeutet nicht zuletzt, die ehemalige Kolonie neu zu bewerten und zu emanzipieren. Amado weist Brasilien in seinem Roman eine Pionieraufgabe zu: Salvador da Bahia wird als „Nabel der Welt“ stilisiert und der mestiço als Ergebnis der inter- kulturellen Begegnungen wird zu einem „Menschen der Zukunft“ deklariert. Im Mittelpunkt des Beitrags steht also die Frage, wie ein Ort durch transkulturelle Prozesse gestaltet wird. Der Bei- trag knüpft damit an Paul Gilroys Aussage an, dass transkulturelle Konzepte nicht nur Dynamik und Unruhe betonen, sondern vor allem auch die mit transkulturellen Prozessen verbundene Kreativität.